650–960

The Khazars' extensive international commercial networks fostered cultural development and openness to other peoples' religions. Originally believers in Shamanism, the Khazar elite appears to have been receptive to other religions, including Islam (via Arab traders in the seventh century), Judaism (via eighth-century Jewish missionaries), and Christianity (via Cyril and Methodius from Byzantium in the ninth century).

Claims that the Khazar king and ruling elite embraced Judaism around the eighth or ninth centuries appeared in a mid-tenth-century account by the Muslim historian Al-Mas'ūdī and in the influential polemical work, The Kuzari,completed in 1140 by the celebrated Spanish-Jewish philosopher and poet Yehudah Halevi. Scholars today are skeptical about such claims and regard as unfounded later speculations that Khazaria was a Jewish state and that eastern European Jews are descendants of the Khazars.

Read more...

The religious beliefs of the Slavic tribes in the Khazar Kaganate, known to us primarily through Christian sources, appear to have been oriented to the personification of nature. Isolated and fearful of the power and mysteries of nature, they formulated divinities who peopled the clouds and the earth, the local fields and forests and rivers. They offered sacrifices and performed rituals in the service of these gods, in practices resembling those of the Celts. Vestiges of these beliefs remained strong in rural areas after the coming of Christianity, often in amalgamation with Christian beliefs.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 48–50;

- Dan Shapira, "The First Jews of Ukraine," in Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry, Volume 26, Jews and Ukrainians, eds. Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Antony Polonsky (Oxford, 2014), 65–68;

- Shaul Stampfer, "Did the Khazars Convert to Judaism?" (June 2014).

860s–880s

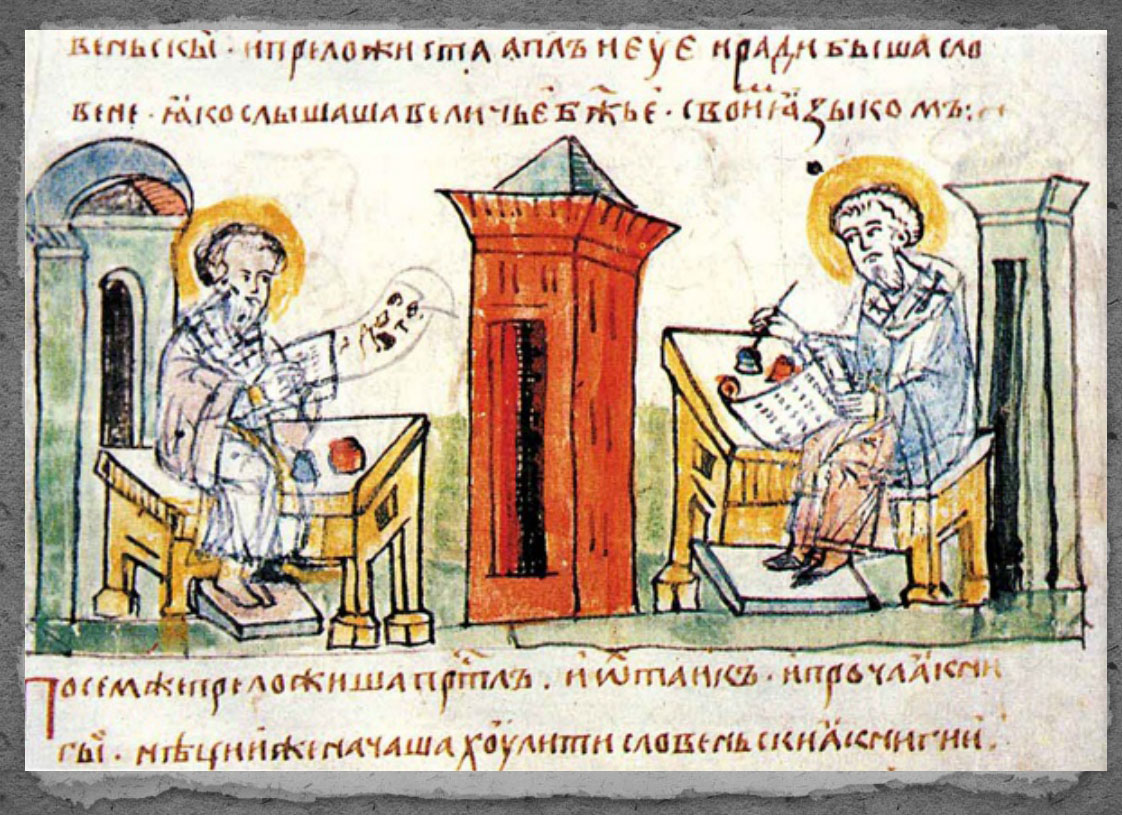

Cyril and Methodius — two brothers who were Byzantine civil servants and fervent Christians — conducted missions to bring Christianity to the Khazars and the Slavs. For this purpose, Cyril (also called Constantine) created an alphabet (the Glagolitic), which later evolved into the Cyrillic alphabet. The new alphabet facilitated the brothers' translation of Greek liturgical works into the new literary language they created, now known as Old Church Slavonic. Scholars have shown that Old Church Slavonic drew from Macedonian dialects spoken in the Balkans. They also have found notable Hebrew influences in the pioneering linguistic work of the two brothers.

Because the alphabet symbols of Cyril's native Greek language did not provide for all the speech sounds in Slavonic, he drew several consonantal symbols from other sources. These included the Hebrew alphabet, which yielded Б (ב), Ц (צ), Ч (ץ), Ш (ש), and Щ (ש) — the phonetic equivalents of b, ts, ch, sh, and shch. Scholars suggest that Cyril and Methodius had learned Hebrew from the Jews of Salonika and Kherson, that they translated part of a Hebrew grammar, and that they produced a version of the Bible, reputedly translated from the original Hebrew.

Although they conducted their missionary work initially among the West Slavs in Moravia, it was among the South and East Slavs that the two brothers (later declared saints) had the most significant impact, including on the development of Ukrainian writing and literature.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 100;

- G. Y. Shevelov, "Saint Cyril" and "Saint Methodius," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1993 articles);

- Hetényi, Martin, and Peter Ivanic, "The Contribution of Ss. Cyril and Methodius to Culture and Religion" in Religions 12(6):417 (2021);

- "Bulgarian Literature" in the Encyclopaedia Judaica, vol. 4 (2nd edition, 2007) and Encyclopedia.com.