1770–1839

Imperial politicization of the churches

The relative status of the two Eastern-rite churches, Orthodox and Uniate, changed significantly with the expansion of Russia, especially after the partitions of Poland, with gains in authority achieved primarily by the increasingly politicized Russian Orthodox Church.

Over the same period that the Kyiv metropolitanate lost many of its adherents in western Ukraine to the Uniate Church, its remaining adherents came under the jurisdiction of the Russian Orthodox Church. By 1770, the title of the Metropolitan of Kyiv had become largely honorific, with jurisdiction limited to the Eparchy of Kyiv. This development had begun in 1721 when Peter I abolished the office of the patriarch and replaced it with a collegium known as the Holy Synod, headed by a secular official (the Chief Procurator) who reported directly to the tsar.

Read more...

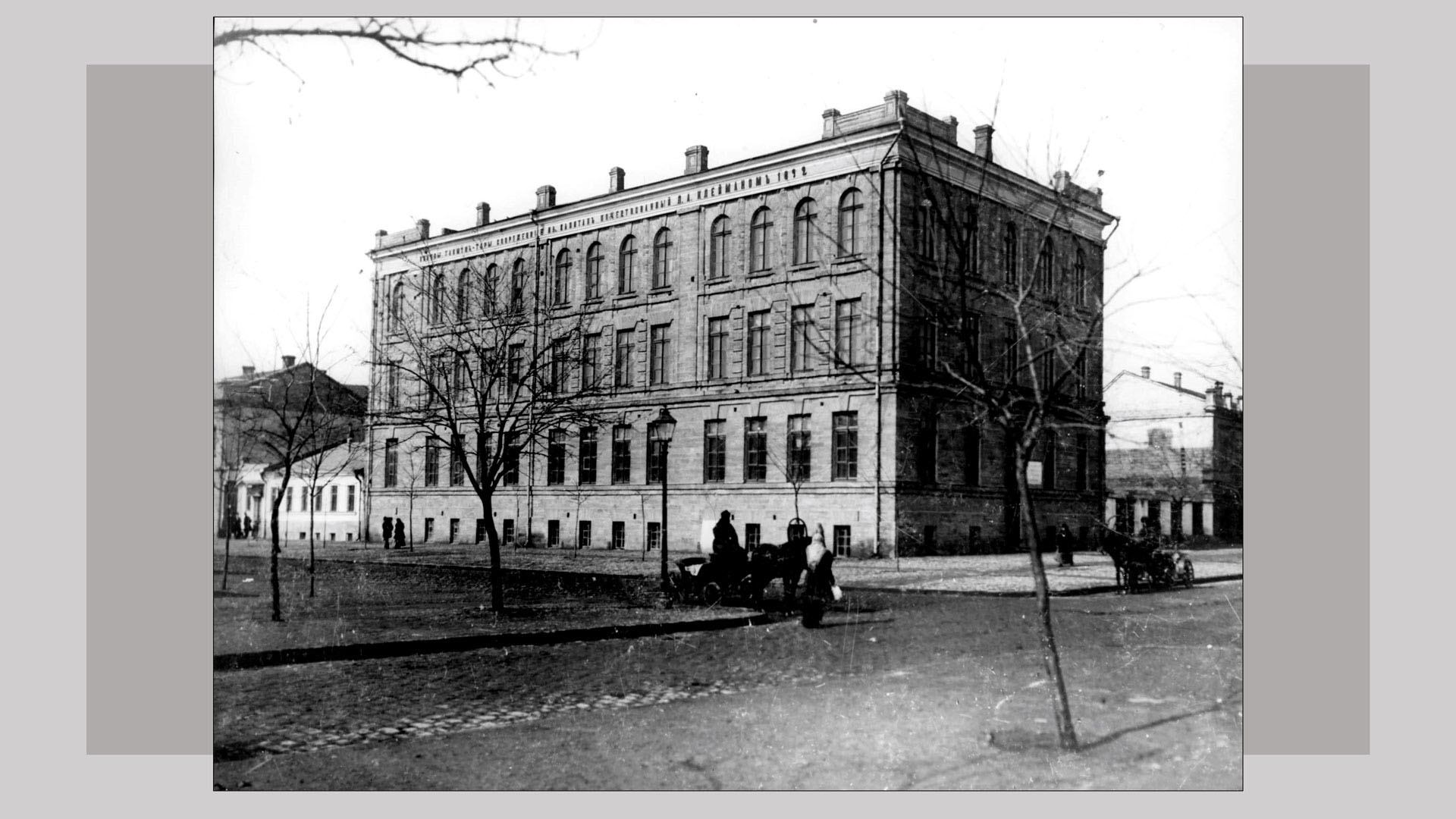

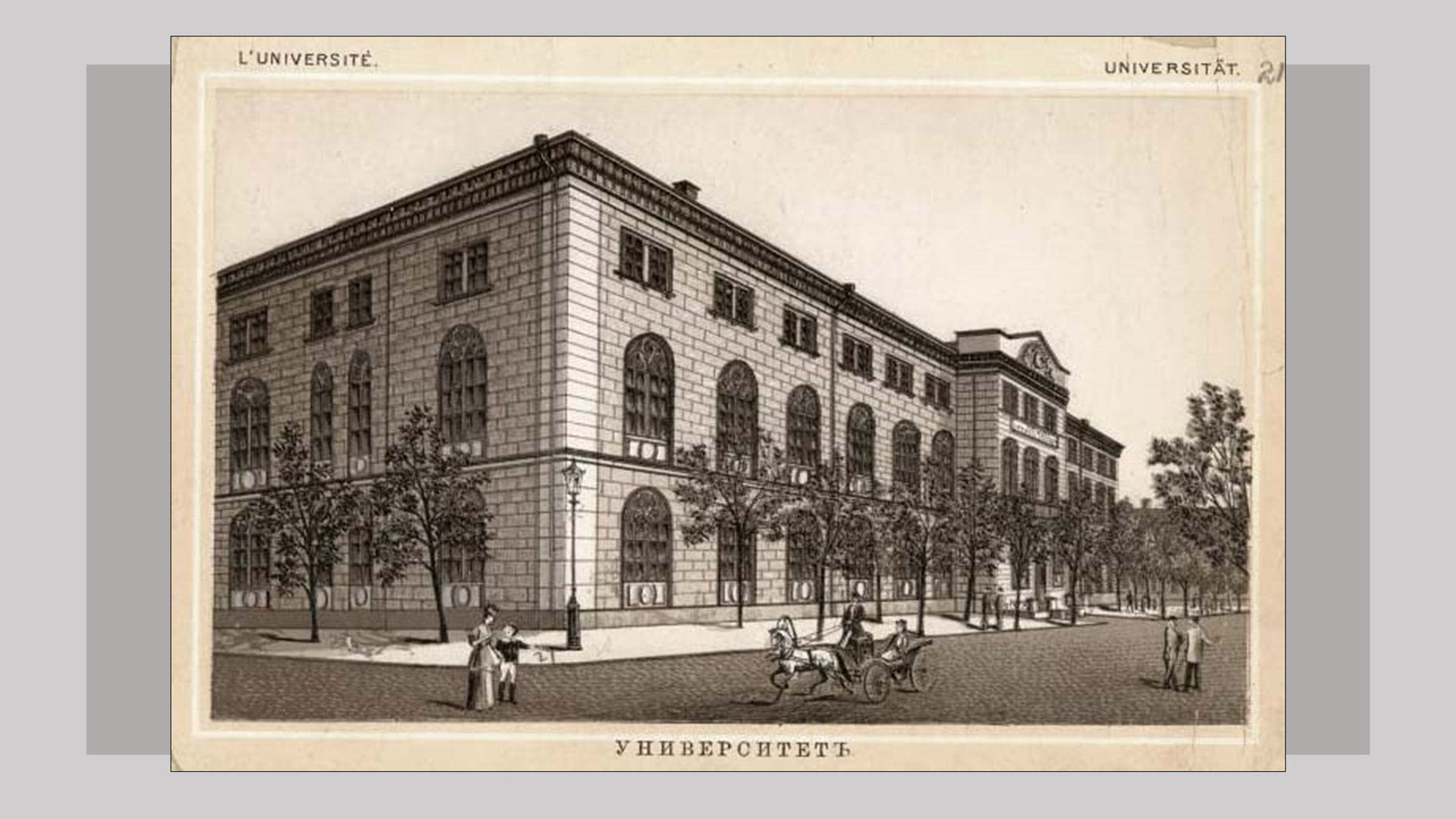

After the abortive 1830–1831 Polish revolt, Tsar Nicholas I and his advisors became concerned about Uniate Ukrainian peasants showing too much affinity with the Poles. Their concern focused attention on the imperative of converting the Uniates to Orthodoxy in order to increase their loyalty to the empire. In 1834, the minister of education, Count Sergey Uvarov, provided a supporting ideology for acting on this imperative — the "Triad of Official Nationality" based on three pillars: autocracy (in terms of loyalty to the tsar and the current regime), imperial national identity, and Orthodoxy. The local Little Russian (Ukrainian) movement appeared well-positioned to play a special role in implementing the new policy. Kyiv, as the "mother of Russian cities," was an important starting point. A first concrete step was establishing the University of St. Vladimir in Kyiv as a vehicle for advancing the Triad ideology.

Conversion of a large number of Uniates occurred in a swift, bold move in 1839, when a Uniate church council, convened with the support of the imperial government, declared the "reunification" of the Uniates with the Russian Orthodox Church. With the support of the tsar and the army to avert a revolt, more than 1600 parishes and (by some estimates) over 1.5 million parishioners in Ukraine and Belarus were "returned" to Orthodoxy overnight — leaving the Greek Catholic Church to continue to function primarily under Habsburg rule. Since Orthodox seminaries used Russian as their language of instruction, the intellectual elite of the church was also being converted from Ukrainian/Ruthenian to Russian nationality.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 382–383;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Ukraine: An Illustrated History (Toronto, 2007), 140–141;

- Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe (New York, 2015), 153–154.

1790s–1820s

Hasidism under tsarist rule

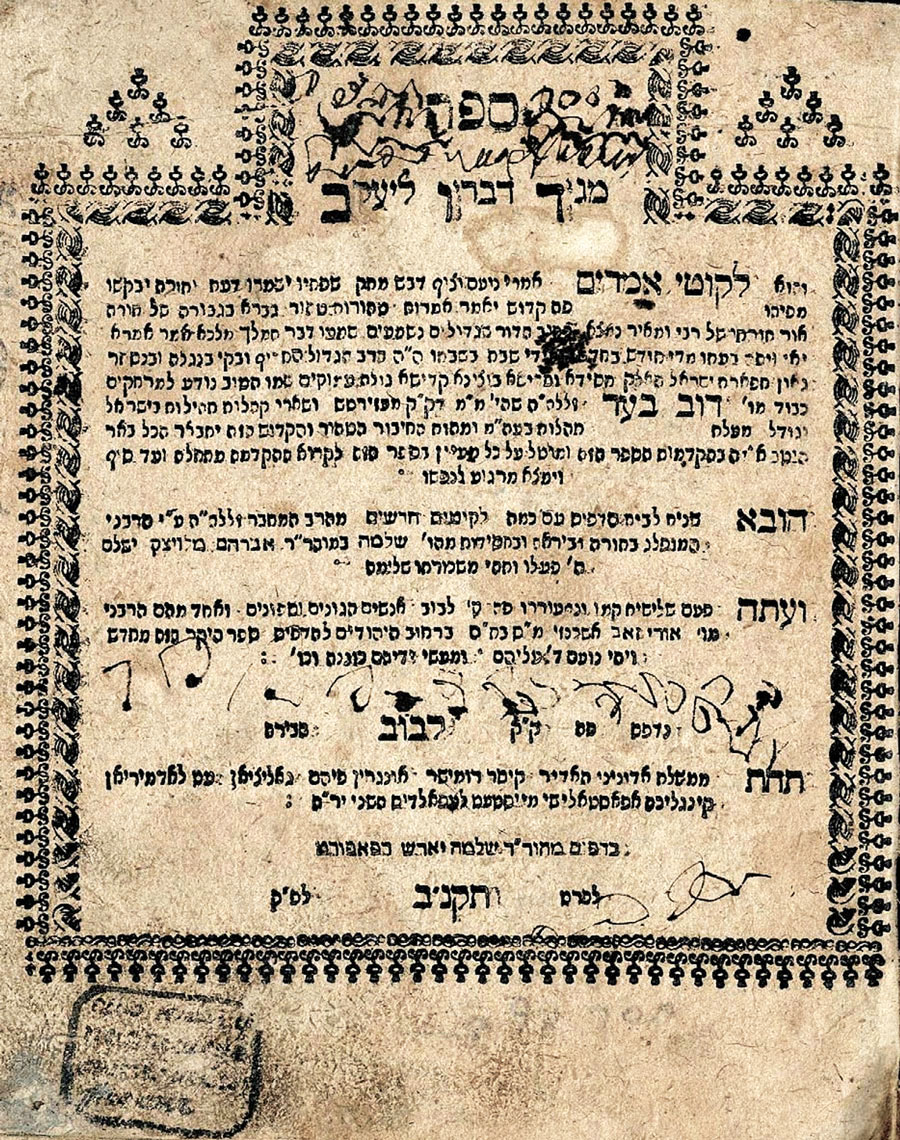

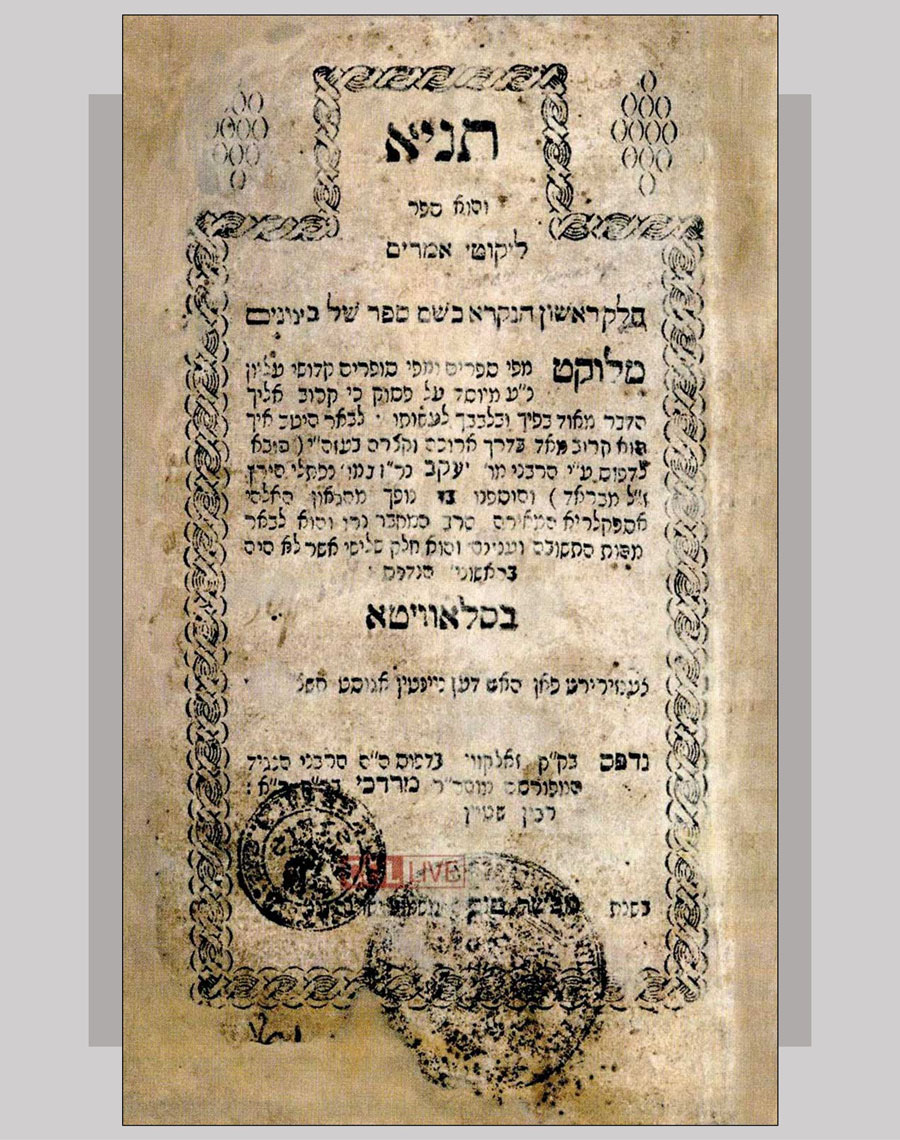

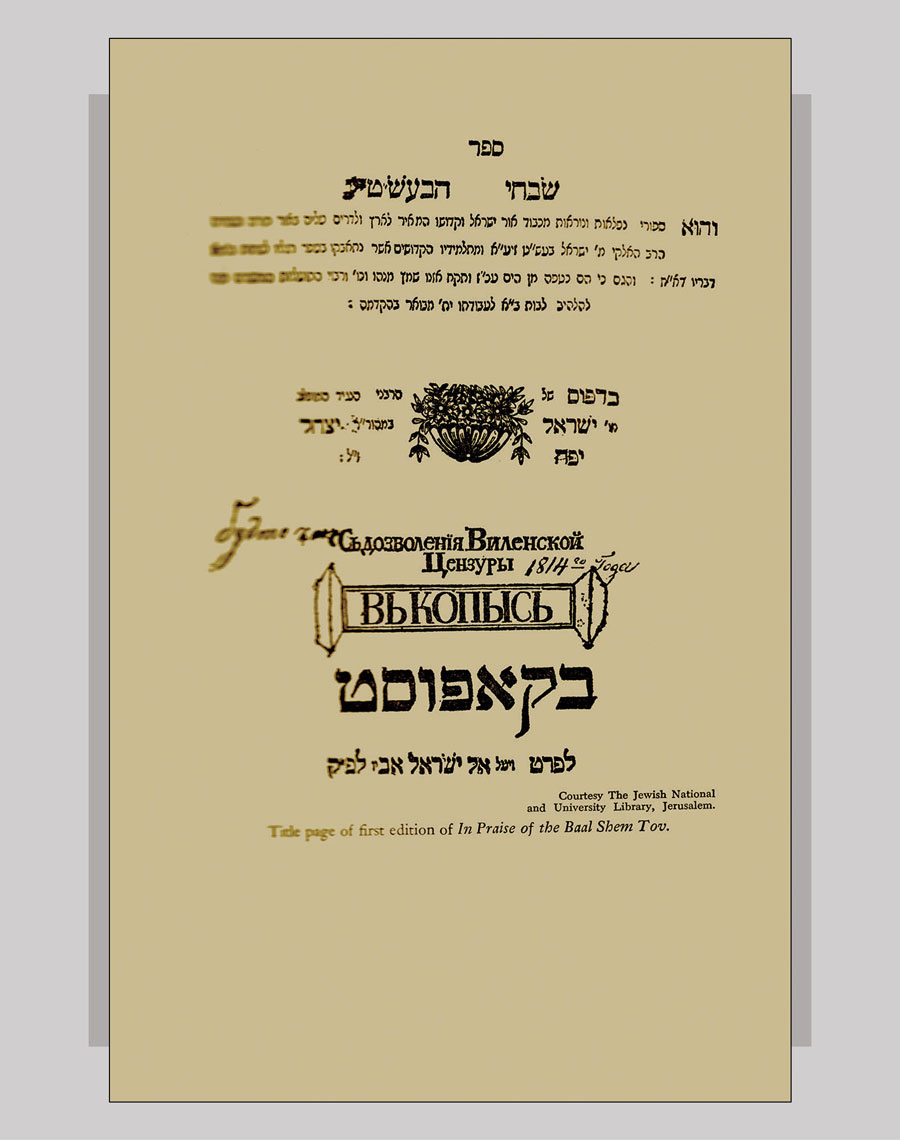

Podolia and Volhynia, the "cradles of Hasidism," came under tsarist rule in the second partition of Poland (1793). By that time, disciples of the Ba'al Shem Tov (the Besht) — in particular, Yaakov Yosef of Polonnoye/Polonne (1710–1784) and Dov Ber, the Maggid (Preacher) of Mezritch/Mezhyrichi (d. 1772) and his disciples — had launched Hasidism as a movement. Their writings, first published in 1780, played a critical role in spreading Hasidic ideas and expanding the movement. Yaakov Yosef, a devoted kabbalist and ascetic, produced influential compilations of teachings attributed to the Besht. In his publications, he also advanced the concept of the tzaddik (Hasidic spiritual leader), setting a pattern for the subsequent growth of Hasidism. The charismatic Dov Ber of Mezritch, regarded as the first systematic exponent of Hasidism, delivered his teachings in oral sermons, subsequently written down and published by his disciples. Unable to travel because of poor health, Dov Ber created the prototype of the Hasidic "court" (extended residence), attracting followers to come to him. These included remarkable personalities — such as Menahem Nahum Twersky (1730–1797), the founder of the Chornobyl Hasidic dynasty and its many offshoots; Levi Yitzhak of Berdychiv (1740–1809), the legendary compassionate "defender" of the Jewish people; and Shneur Zalman of Liady (1745–1812), the founder of Habad Hasidism.

Read more...

Hasidism reanimated the emotional dimension of Jewish religious practice and experience. It did so through ecstatic prayer, melodies and dance, and an overall notion of joy in daily life, based on the belief that God is omnipresent throughout the material world. In addition to appealing concepts, new social and institutional structures helped popularize the movement. These include the emergence of numerous small and intimate prayer houses (enabled by the tsarist statute of 1804), an emphasis on group bonding, and charismatic spiritual leadership by holy men (tsadikim in Hebrew, or rebbes in Yiddish).

Hasidism expanded its reach as new tsadikim arose and attracted devoted followers to their "courts" across the Pale of Settlement and beyond. Most tsadikim established Hasidic dynasties, passing on the mantle of leadership to their sons, close relatives, or disciples. An exception to the dynastic pattern of Hasidic leadership was that of Nahman of Bratslav (1772–1810), a great-grandson of the Besht. For his followers, Rabbi Nachman remained the one-and-only rebbe, even beyond his death. His influence was extensive, eventually reaching beyond Hasidic and even Jewish circles. (Since the 1990s, the Bratslav Hasidim have experienced a remarkable renaissance, centred in Uman.)

Acceptance of Hasidism as a legitimate part of the traditional world increased as the number of its adherents grew, especially when that world came under assault by Jewish Enlightenment activists and the forces of modernity. In the 30 years between the third partition of Poland and the reign of Nicholas I, Hasidism expanded from Podolia and Volhynia to the Kyiv region and other parts of the Pale of Settlement. After 1815, however, the movement's center of gravity shifted away from tsarist Russia, predominantly to Austrian-ruled Galicia.

sources and related

- David Assaf, "Hasidism: Historical Overview," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010);

- Michael Stanislawski, "Russia: Russian Empire," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010);

- David Biale et al., Hasidism: A New History, (Princeton and Oxford, 2018), 7–9, 62–70, 77–99, 103–117;

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) II, 227, 291;

- Marcin Wodziński, Historical Atlas of Hasidism (Princeton University Press, 2018), 16–19, 38–40.

Related

Chapter 4.4 1742–1790s (Read More)

Chapter 5.4 1815–1867

1798

Poltava noble Ivan Kotliarevsky published the heroic-comic epic poem Eneyida, the first poetic work in modern vernacular Ukrainian, ushering in modern Ukrainian literature. This work is a parody of the post-Trojan war events described by the Roman poet Virgil, a parody in which the protagonists are Ukrainian Cossacks. When the poem was written, popular memory of the Cossack Hetmanate was still alive, and the oppression of tsarist serfdom in Ukraine was at its height. Kotliarevsky's satire of the mores of the social estates during these two distinct periods, combined with the use of spicy colloquial peasant idioms and Cossack expressions, ensured the poem's popularity among his contemporaries. In a subtle manner, the poem also delivered the politically provocative message that Ukrainians are an ancient people, inspiring later Ukrainian writers and thinkers with this perspective.

Jewish characters also appear in Kotliarevsky's grand comic panorama of Ukrainian society, without particular emphasis, alongside members of other religions, races, and professions. The term orendar (leaseholder) is used to describe an innkeeper, with no indication that he might be Jewish and no negative connotations.

sources

- "Kotliarevsky, Ivan," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence (Toronto, Second Edition, 2018), 166;

- Myroslav Shkandrij, Jews in Ukrainian Literature. Representation and Identity (New Haven, 2009), 11.

1790s–1900s

Itinerant Ukrainian bards called kobzars, who had been popular since the fifteenth century, including at royal courts, fell on hard times after the decline of the Cossack State. They gradually joined the ranks of mendicants, playing and begging for alms at rural marketplaces. In the late 18th century, the occupation of kobzar became the almost exclusive province of the blind and crippled, who organized kobzar brotherhoods to protect their group interests. Taras Shevchenko immortalized the kobzars in his poetry and drawings.

Read more...

From the 1870s, the tsarist regime persecuted the kobzars as propagators of Ukrainophile sentiments and historical memory. In the early 1900s, ethnographers took an interest in their artistry. Hnat Khotkevych, the "first seeing kobzar" (who composed 69 works for the bandura), successfully lobbied on their behalf. Thereafter, kobzar concerts became frequent events in many Ukrainian and Russian cities. Bandura schools were established, and in 1907 Khotkevych published the first history and manual of bandura playing.

sources

- Mykola Mushynka, "Kobzars," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1988).

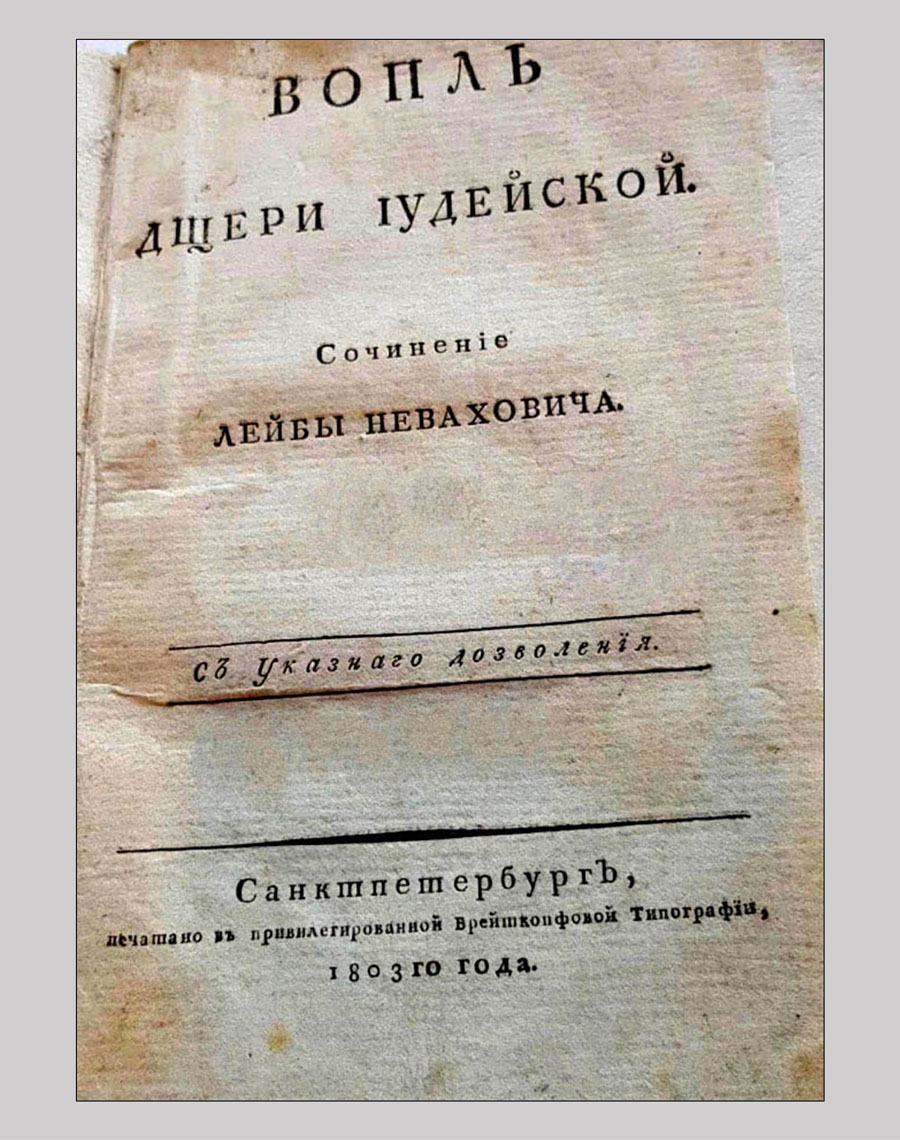

1803

Judah Leib Nevakhovich, a proponent of the Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment) from Podolia, published a pamphlet appealing to the authorities and the people of Russia to show a spirit of tolerance and justice toward Jews. The pamphlet, entitled Vopl dshcheri iudeiskoi (The Wailing of the Daughter of Judah), was dedicated to the Russian Minister of Internal Affairs Count Viktor Kochubei, a scion of the Ukrainian Cossack aristocracy. In it, Nevakhovich argued against the undeserved accusations levelled at the Jews for centuries and advocated greater appreciation of their humanity and potential to be valuable citizens. As he said: "You search for the Jew in man. Search for the man in the Jew, and you will no doubt find him."

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) I, 343–344.

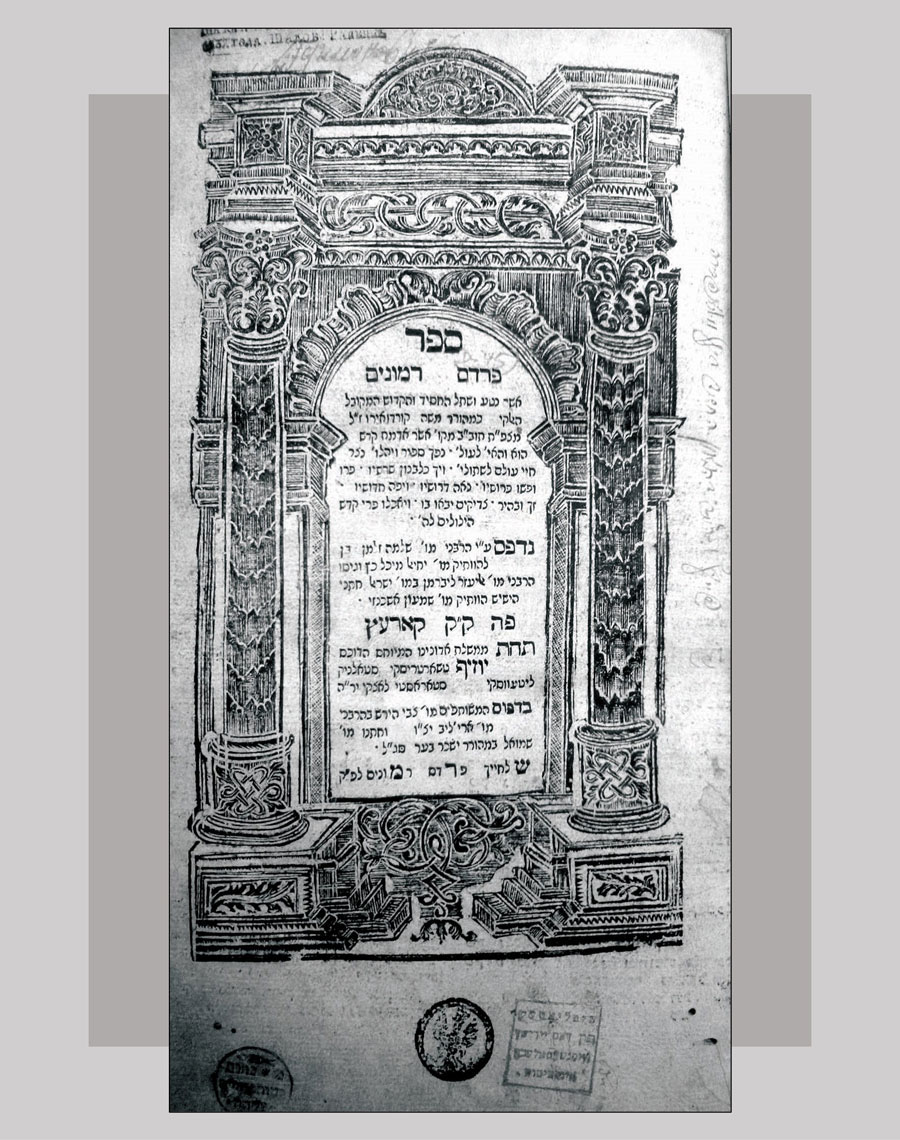

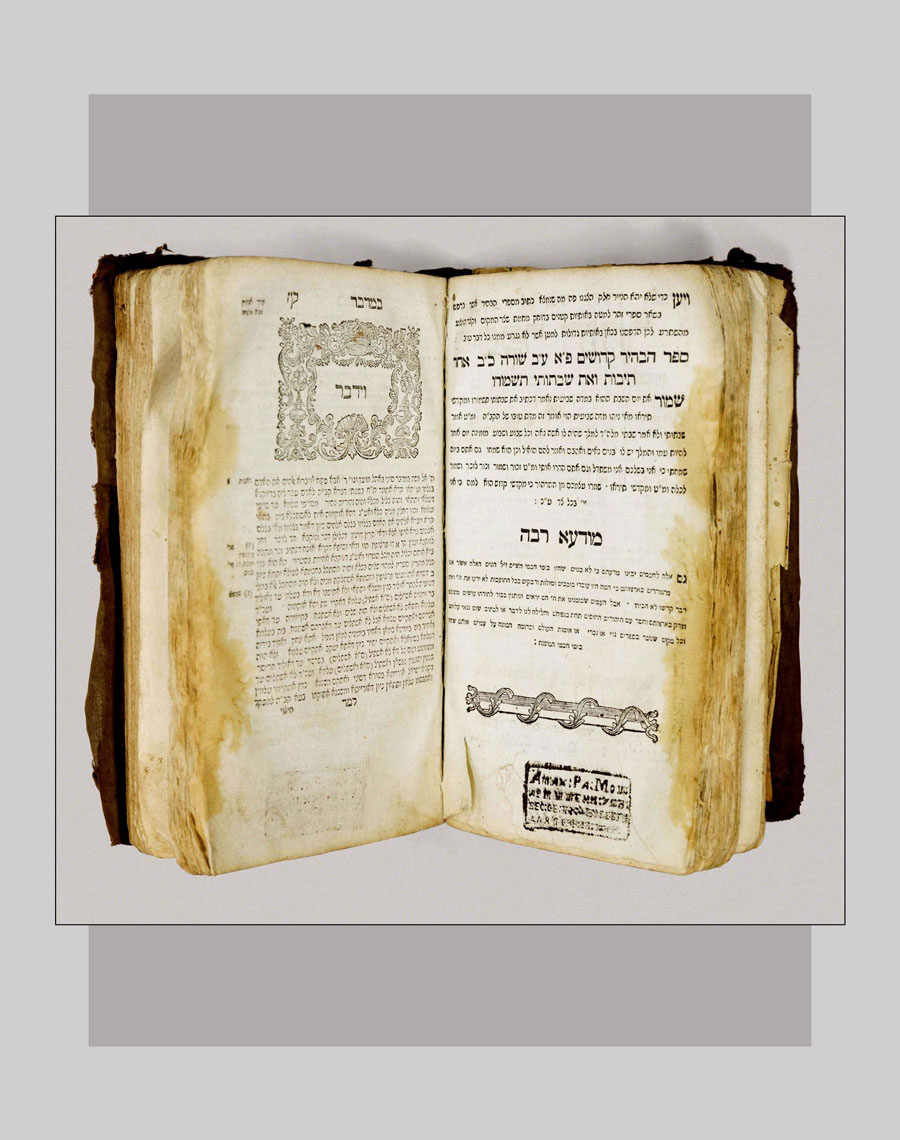

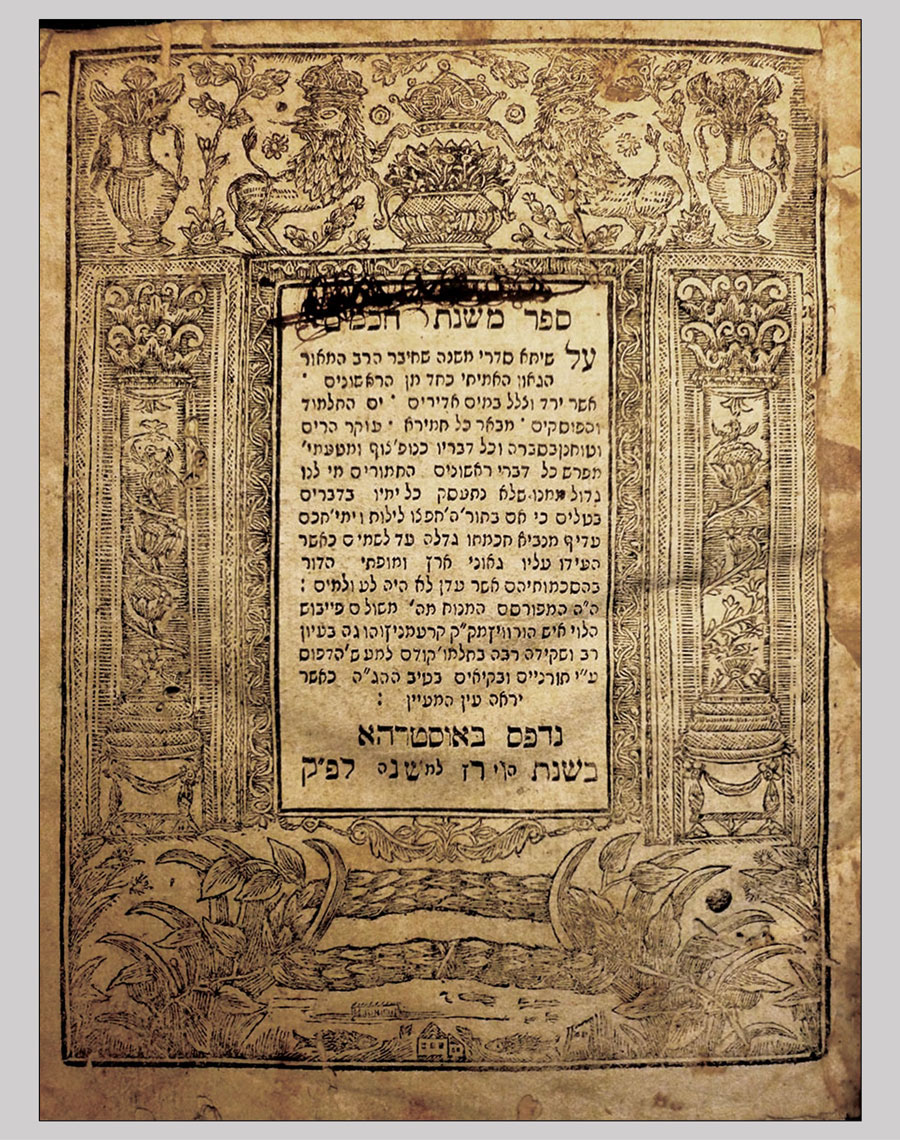

1780s–1850s

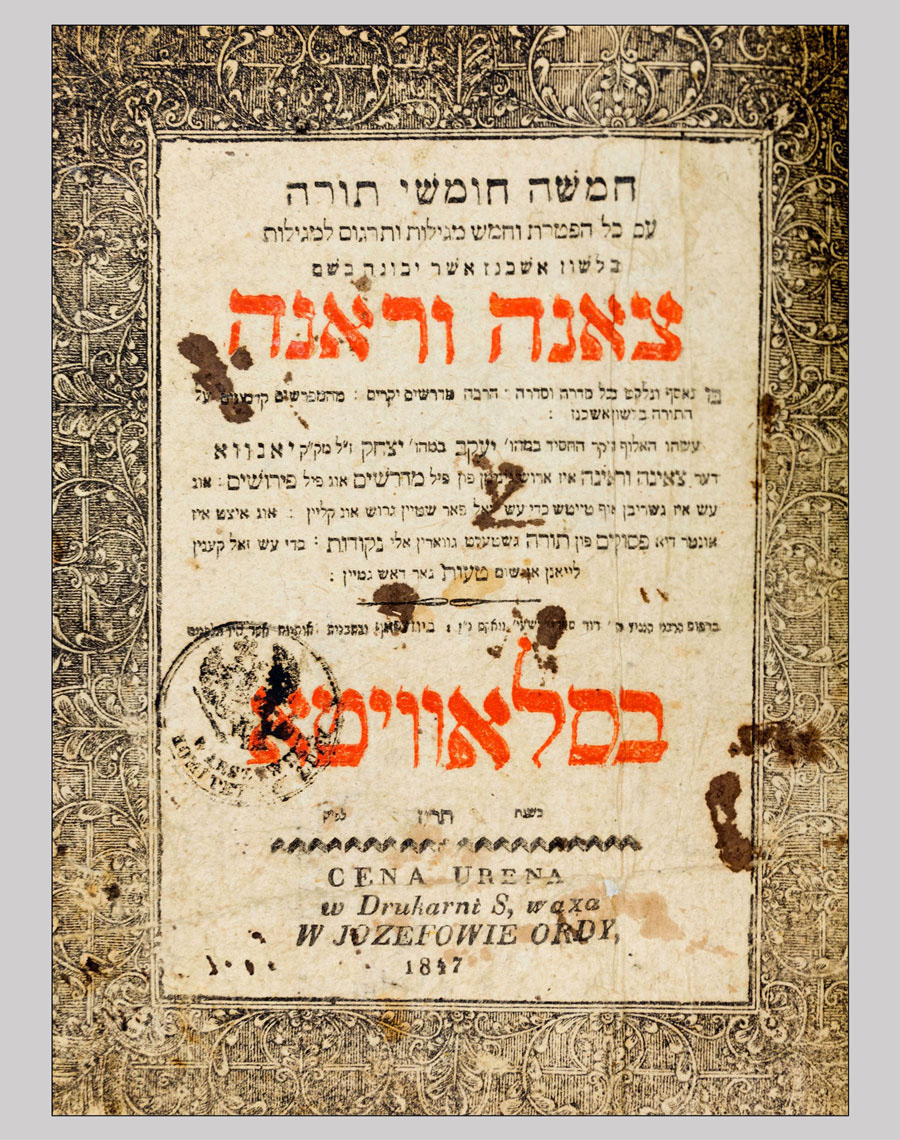

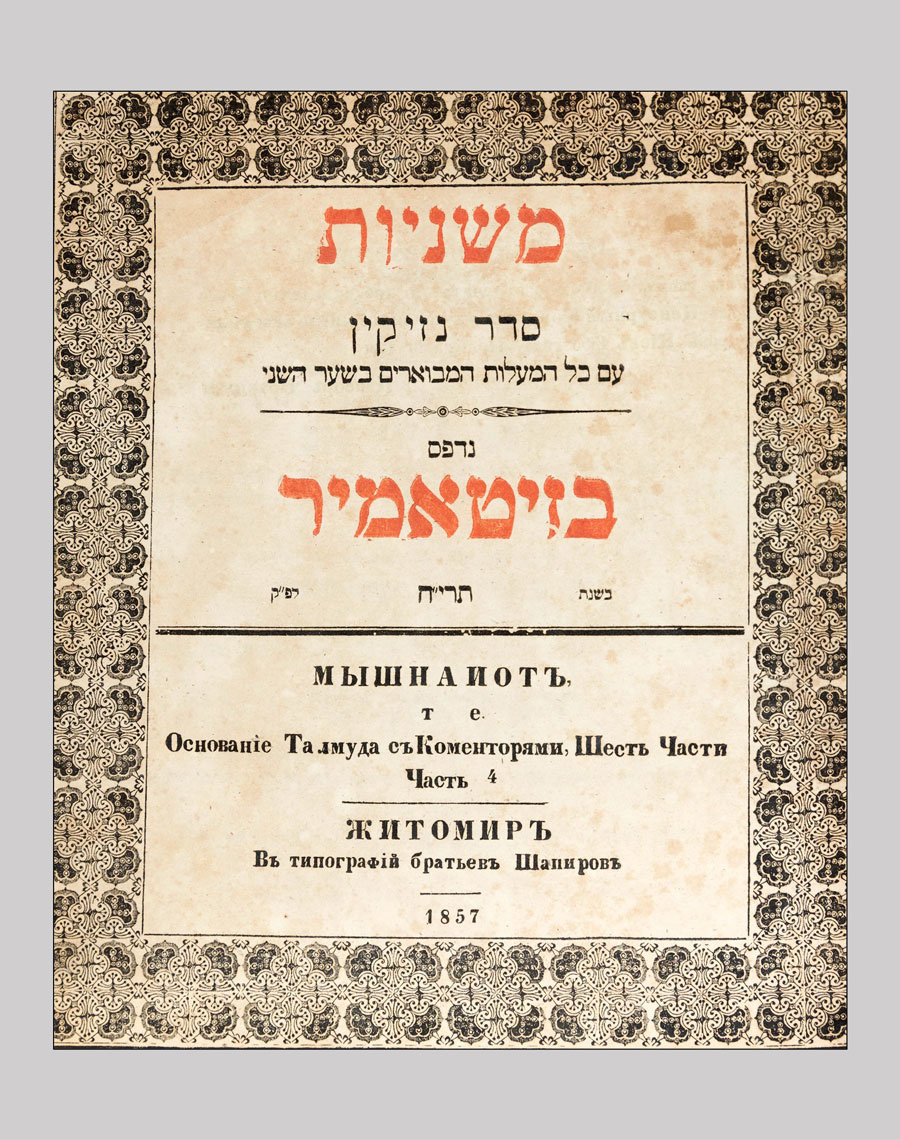

Hebrew and Yiddish book production

The 1780s ushered in an extraordinary period in the history of Hebrew book printing in Ukrainian lands, as printing establishments sprung up in more than fifty towns — until an 1836 censorship law reduced such establishments to only two, in Zhytomyr and Vilna. The proliferation of printing presses during this period was a response to increased demand for prayer books and other religious texts due to population growth in the Pale of Settlement. The lively publication scene also reflected internal community polemics, in particular between the Hasidim and their opponents, both misnagdim (traditionalists) and maskilim (modernists). Among the most prominent publishers of the era was the Shapira family of Slavuta, famous for producing three beautiful editions of the Babylonian Talmud, editions of the Zohar, and numerous Hasidic works.

sources

- Kenneth B. Moss, "Printing and Publishing after 1800," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1790s–1812

The majority of traditional Jewish religious leaders in Eastern Europe, including the prominent Gaon of Vilna, were deeply suspicious of campaigns to emancipate and integrate the Jews of the Russian Empire. They believed that the emerging integrationist ideologies had the conversion of Jews as their aim. In a similar vein, Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liady, the founder of Habad Hasidism, expressed the view in 1812 that a Russian victory over Napoleon would be preferable since Napoleon's revolutionary ideas would serve to undermine traditional Jewish religious belief and practice. At the time, the memory of the Frankist heresy and conversions were still fresh, and all calls for the "reform" or "transformation" of the Jews were seen as a prelude to assimilation and Christianization

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) I, 186–187, 207–208.

1810s–1840s

The developing grain port of Odesa became an important centre of the Haskalah (Jewish enlightenment), especially after the arrival of grain dealers from the Galician town of Brody, who had imbibed the modernist ideas prevalent in their native town.

Read more...

About 300 Galician Jewish families settled in Odesa in the 1820s and 1830s and soon assumed communal leadership, overseeing local synagogue life and launching a modern Jewish school for boys in 1826. By 1835, this school had 289 pupils, while its sister girls' school created in the same year had sixty. The curriculum comprised Bible studies, mathematics, physics, history, geography, German, French, Hebrew, and Russian, among other subjects.

A number of factors, unrelated to the appearance of the Galicians, contributed to the receptivity of Odesa's Jews to modernizing trends, including the city's remoteness from established traditional centers of Jewish life, its heady materialism, and its rapid rise as a Russian cultural centre. Beyond modernizing Jewish religious expression, segments of Odesa's Jewish population were keen to acculturate into the dominant surrounding non-Jewish culture and the broader European culture. The Jewish elite in Odesa, which had common commercial interests with the non-Jewish elite, was open to such acculturation. Even the fairly traditionalist Jews were eager to integrate non-Jewish cultural forms into their lives, as evidenced by their enthusiasm for concerts, the theatre, and especially the opera. Acculturation soon coupled with growing demands for civic emancipation. While some community leaders expressed concern about the growing number of disaffected Jewish youth, they remained optimistic about the Russian government's policies, especially after the accession of Alexander II in 1855.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) I, 367;

- Steven J. Zipperstein, "Jewish Enlightenment in Odessa: Cultural Characteristics, 1794–1871," Jewish Social Studies, Vol. 44, No. 1 (1982), 19–36;

- Steven J. Zipperstein, The Jews of Odessa: A Cultural History, 1794–1881 (Stanford University Press, 1986), 63–69;

- Steven J. Zipperstein, "Odessa," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1827–1849

Over this period, Mykhailo Maksymovych published three anthologies of Ukrainian folk songs, which inspired interest in Ukrainian folklore across the Slavic world. Among his numerous publications, in an extensive range of disciplines, were other works that had an impact on the Ukrainian national awakening. These include many papers in Slavic philology, using examples from Ukrainian, and works on Ukrainian literature and history, especially on the history of Rus' and Kyiv and the Cossack period. He also translated the Psalms into Ukrainian.

Maksymovych exemplifies the cultured offspring of the Cossack officer class, who initiated the Ukrainian national movement in tsarist Russia. In 1834, Maksymovych became the first rector at the university in Kyiv, a city that emerged as the center of the Ukrainian movement in the 1840s. The other primary center was Kharkiv, where a university had been founded in 1805 and periodicals such as The Ukrainian Herald and The Ukrainian Journal promoted Cossack history and popularized the term “Ukraine,” which had been used by Khmelnytsky earlier. However, the tsarist authorities repressed the movement’s development, severely restricting publication or education in the Ukrainian language and arresting or exiling the leaders of the movement.

sources and related

- Oleksander Ohloblyn, "Maksymovych, Mykhailo," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1993).

- John-Paul Himka, Ten Turning Points: A Brief History of Ukraine.

Related

Chapter 6.4 1890s–1900s (Ukrainian ethnography)

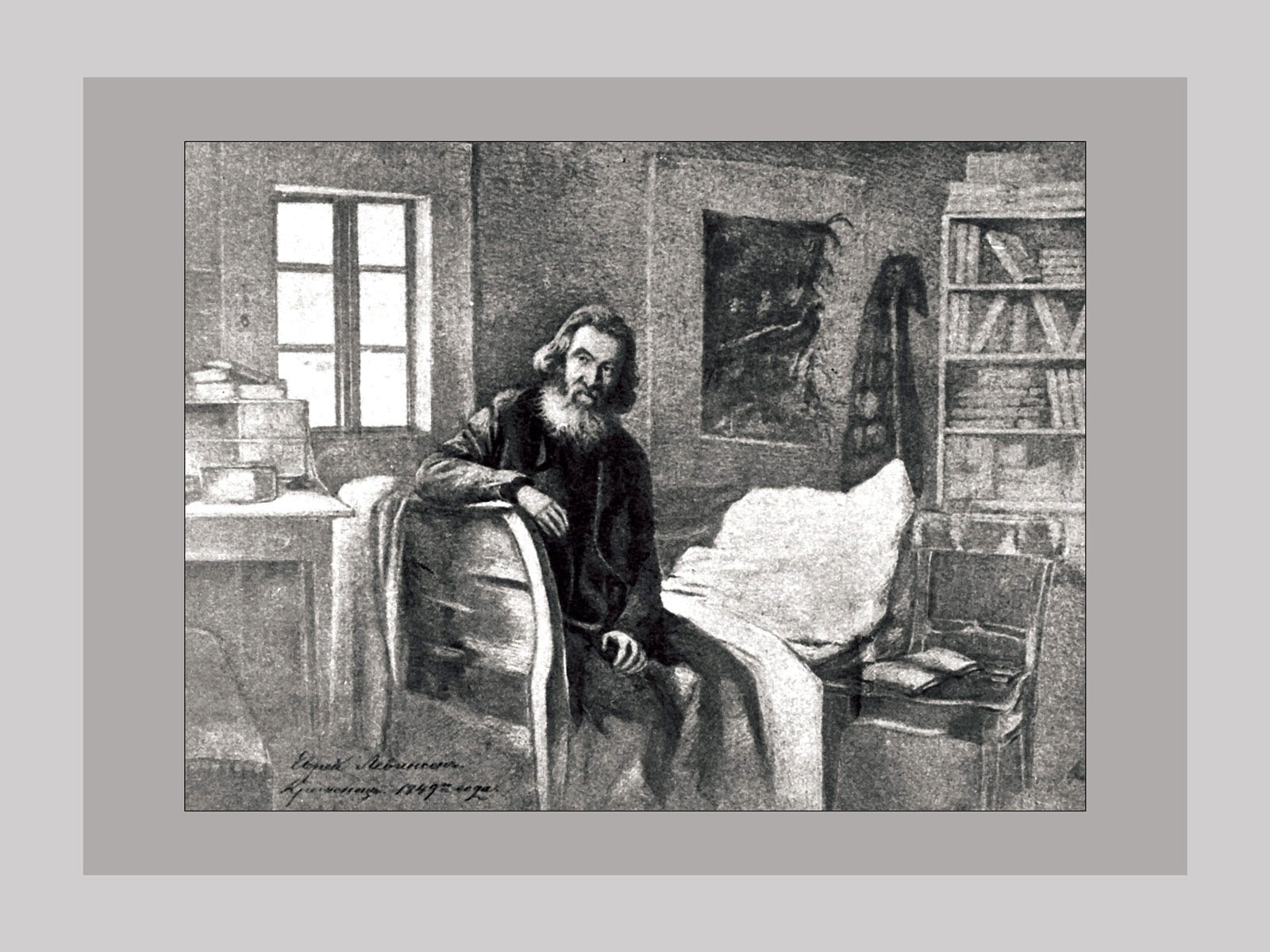

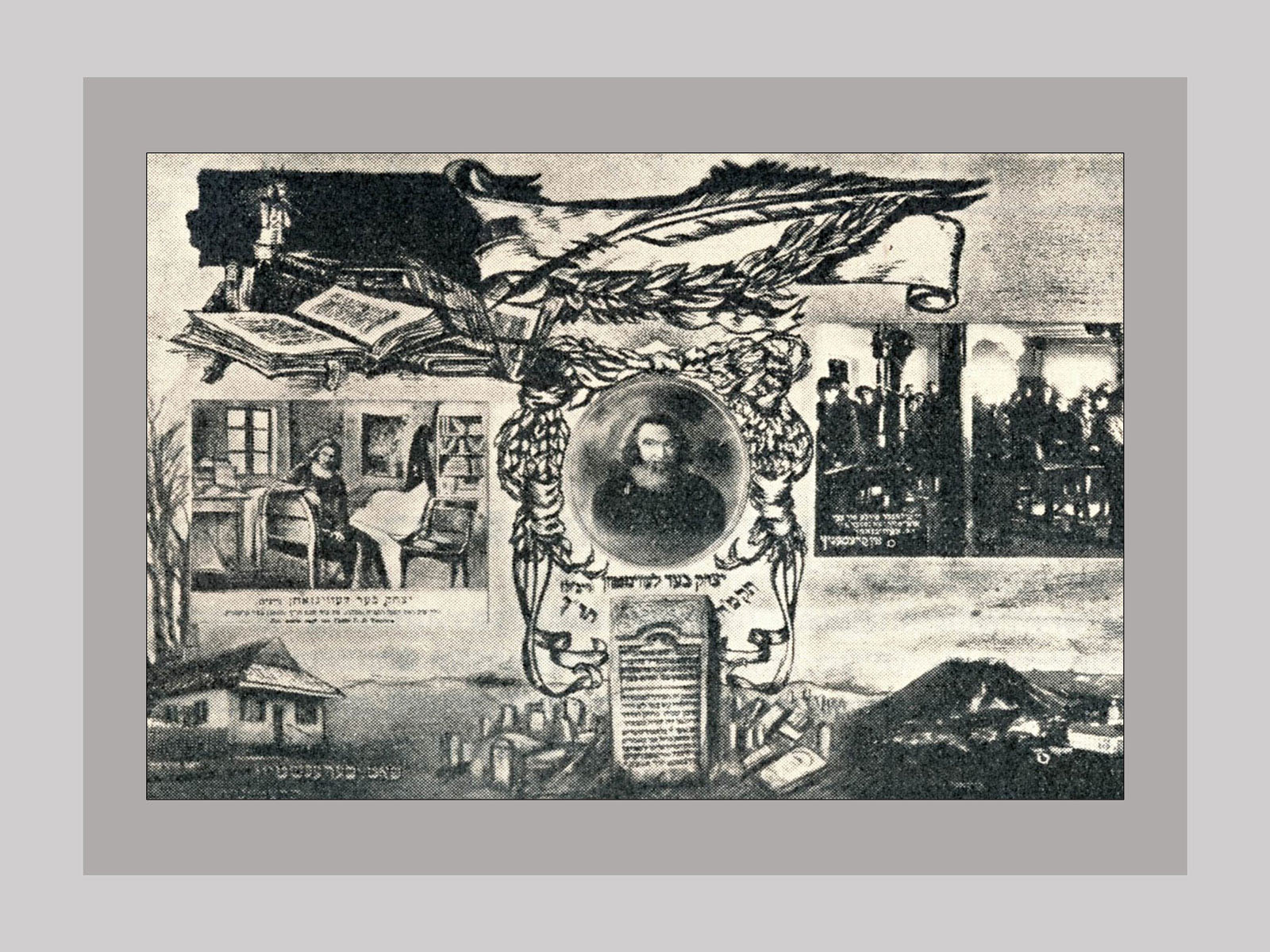

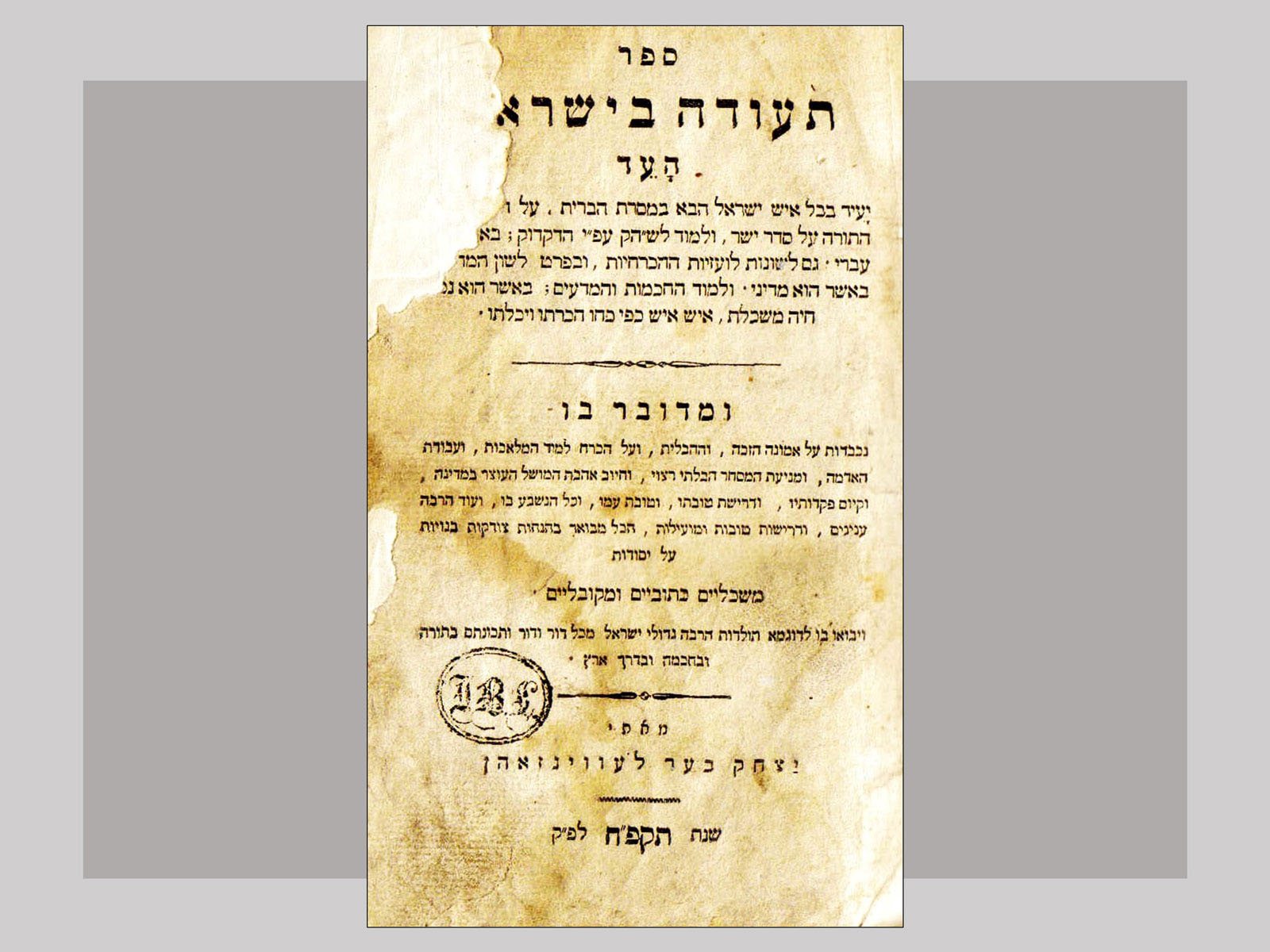

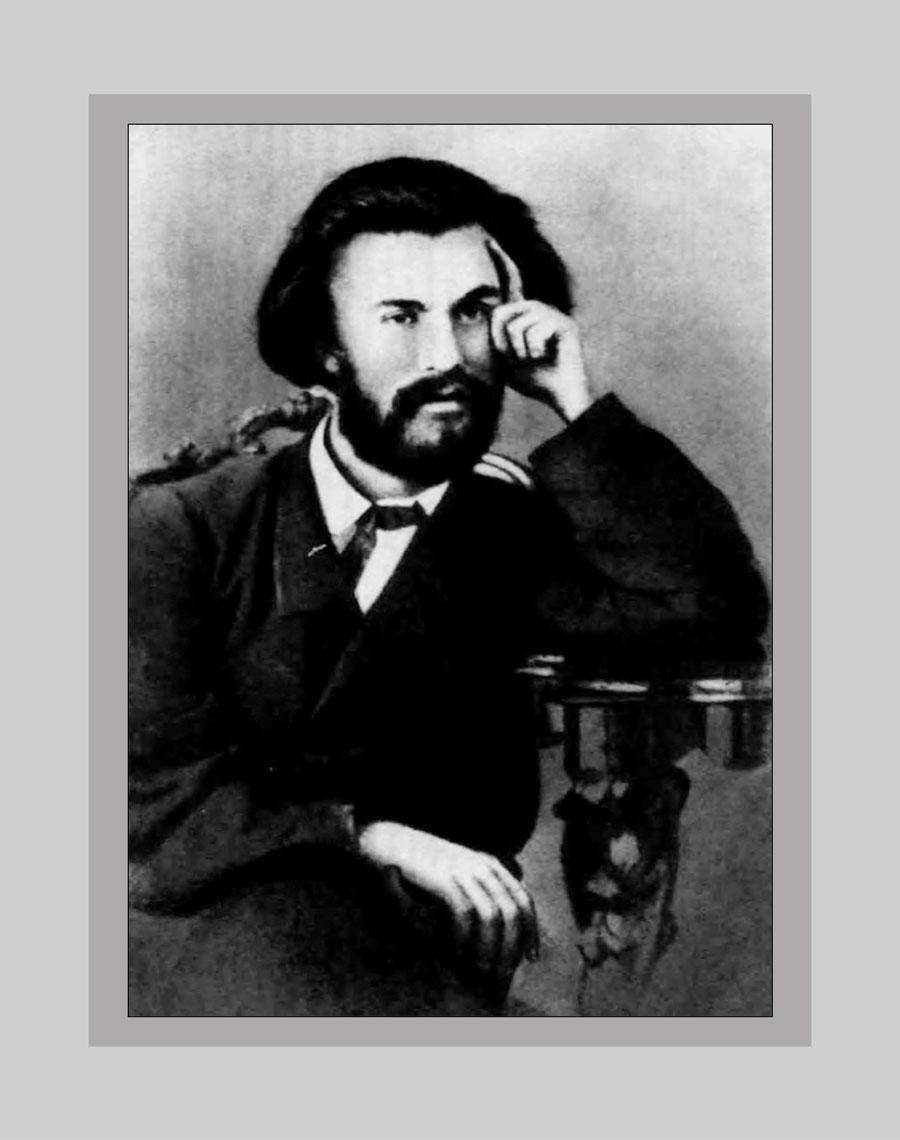

1828–1838

The influential writer and maskil (proponent of the Haskalah) Yitshak Ber Levinzon published his book Te'udah be-Israel (Mission in Israel) with the help of a Russian government subsidy. The book formulated the distinctive ideology of the Haskalah in the Russian Empire, calling for reform of the Jewish educational system (including the teaching of Hebrew and the introduction of secular subjects), reform of Jewish religious and communal institutions, and the "productivization" of Jews. A maskil of the younger generation acknowledged that this book alone made him into a man.

Read more...

In his 1838 publication, Beit yehudah, Levinzon developed his vision further and included a five-point plan for reforming Jewish life in the tsarist empire. The very first point was establishing a modern educational system for both boys and girls. His concern for the education of girls was shared by other maskilim, many of whom considered this a necessary precondition to wider reform.

Levinzon produced influential books and memoranda to prominent government officials while living an ascetic, hermit-like existence in a one-room house on the outskirts of Kremenets/Kremianets (Volhynia).

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. I, 366, vol. II 346;

- Pinkas Kremeniec: A Memorial (Tel Aviv, 1954), 71–76.

1836

Denunciations of the burgeoning Hasidic literature by proponents of the Haskalah led the Minister of the Interior to introduce a new censorship law for books using Hebrew type. The law made it illegal to possess any uncensored Hebrew books or books imported without government permission and required that all such books be presented to the local police for examination by a special commission within a year. The authorities also shut down all presses using Hebrew type, except for two, one in Vilna and one in Kyiv; the latter subsequently relocated to Zhytomyr. These restrictive measures proved ineffective. The number of books submitted soon overwhelmed the police's vetting capacity, and the following years saw the further expansion of the production of books in Hebrew and Yiddish.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. I, 363.

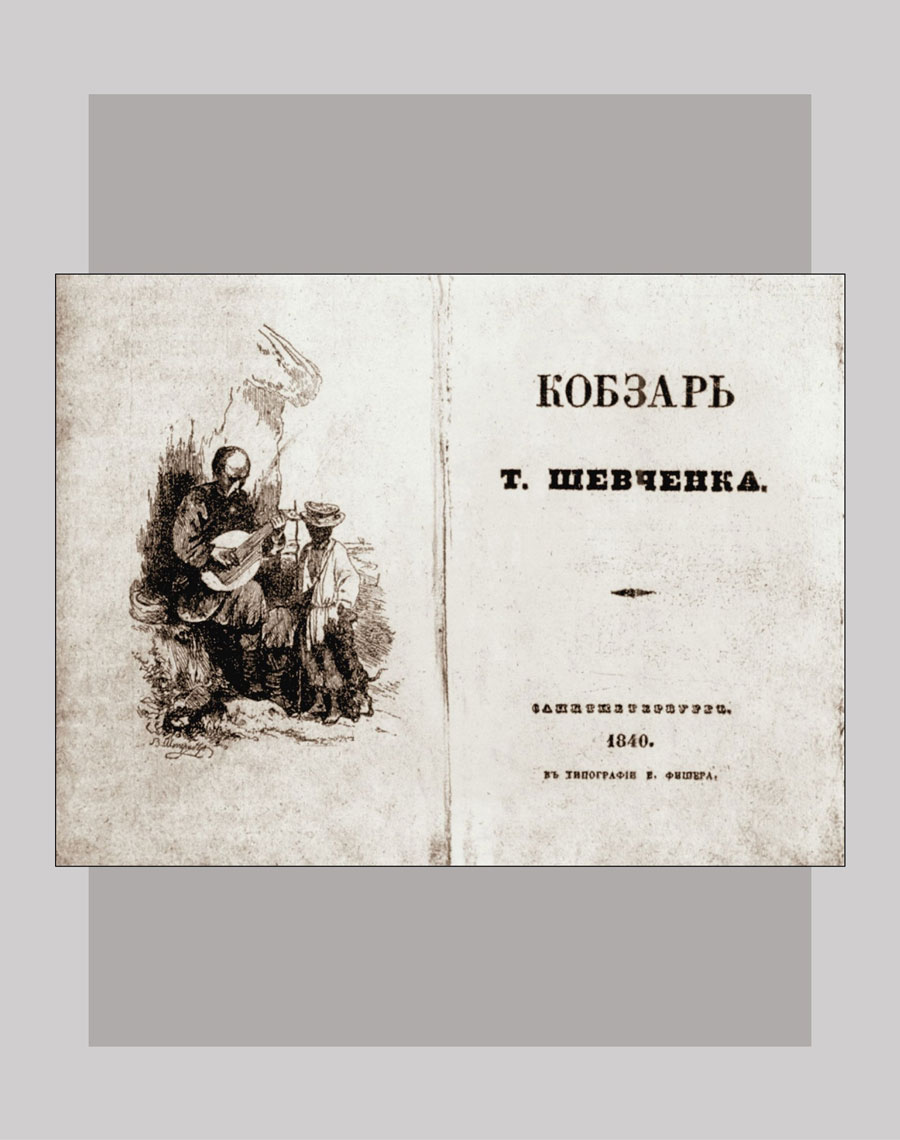

1840–1841

Taras Shevchenko's collection of poems Kobzar (The Minstrel,1840) and his epic poem Haidamaky (The Haidamaks, 1841) were published. These works played a significant role in shaping modern Ukrainian national self-consciousness and have become classics of Ukrainian literature. The contribution of these two works lies first of all in inspiring confidence in Ukrainian as a powerful literary language. The eminent Ukrainian writer Ivan Franko wrote that Kobzar "immediately revealed… a new world of poetry. It burst forth like a spring of clear, cold water and sparkled with a clarity, breadth and elegance of artistic expression not previously known in Ukrainian writing." These works also instilled national pride, as they treated the historical exploits of the Ukrainian people, depicted as an independent nation until subjugated by Muscovite and Polish rulers.

Read more...

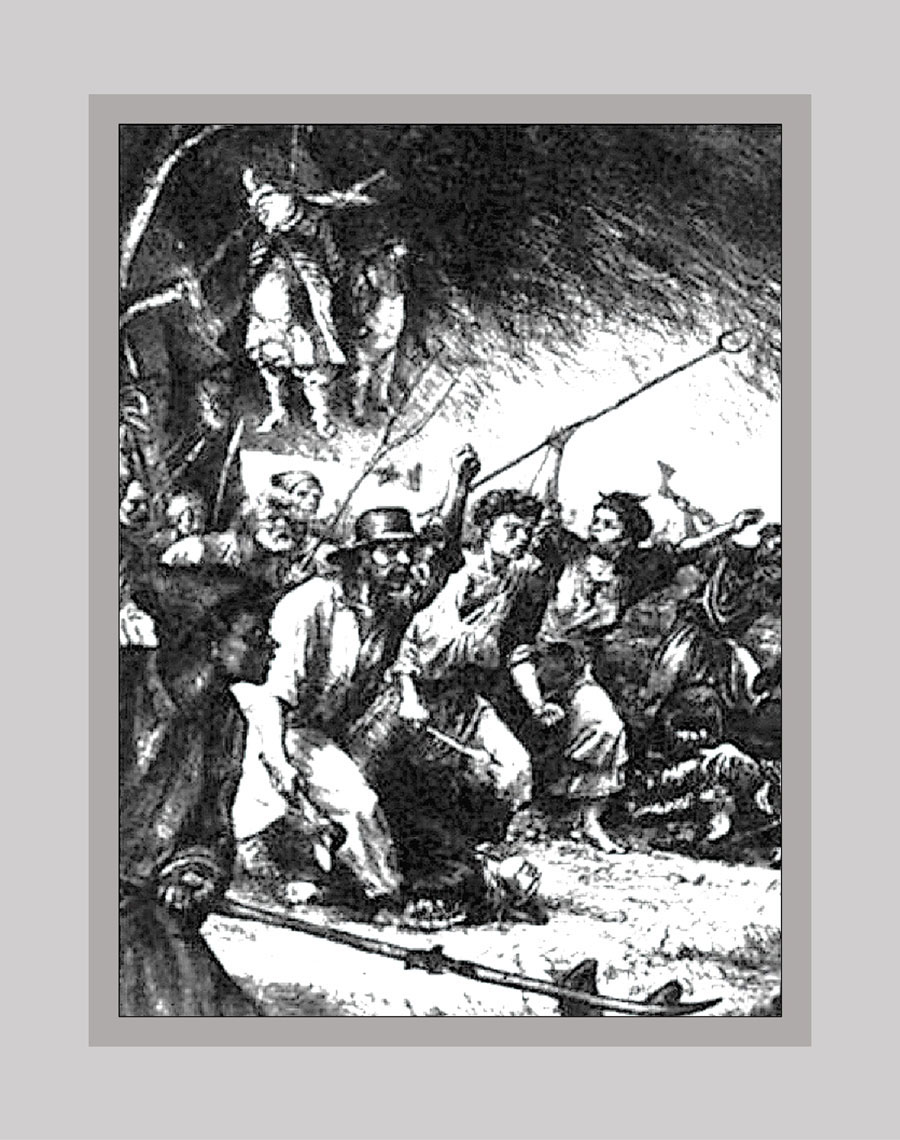

While Kobzar contains mainly Romantic ballads, Shevchenko's more politically provocative work, Haidamaky, relates an epic tale of popular rebellion against serfdom and national oppression — understood as such by Russian censors, who hindered its dissemination. It depicts the 1768 revolt of Ukrainian serfs under the command of Cossack leaders, during which several thousand Poles and Jews were massacred in Uman in central Ukraine. The poem's main themes are violence and vengeance, and the trauma and loss that generally follow violence. According to literary scholar, former dissident, and Ukrainian social activist Ivan Dziuba, the concluding section of Haidamaky is "not an apology for revolutionary bloodshed… but a tragedy in the Shakespearian manner of clearly giving a name to human madness."

The poem's main Jewish character, the tavern-keeper Leiba, is initially portrayed negatively as a demanding taskmaster and stereotypical miser counting his money at night. However, there is also an empathetic depiction of him as a victim of the Polish confederates who rob and whip him, and appreciation for his commendable actions in helping the main character, young Yarema, rescue his beloved Oksana.

Shevchenko's poems drew inspiration from the Hebrew Bible, especially the Psalms, as he wrestled with the theme of revenge. In later poems, Shevchenko refrained from attacks against "Poles" and "Jews" and upheld the ideal of understanding between peoples.

Beyond the literary and artistic expression of the raw emotions of the serf class, Shevchenko later joined a group of Ukrainian intellectual activists who dreamed of emancipating the serfs and replacing the centralized Russian autocracy with a federative democracy. This led to his arrest in 1847 and exile to a penal colony in Kazakhstan. He was allowed to return to Ukraine in 1859, but died two years later.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 385;

- Myroslav Shkandrij, Jews in Ukrainian Literature. Representation and Identity (New Haven, 2009), 22–28, 31;

- Ivan Dziuba, "Shevchenkovi Haidamaky z vidstani chasu," Suchasnist 6 (2004): 67–92 (cited in Shkandrj, 25);

- The Taras Shevchenko Museum;

- John-Paul Himka, Ten Turning Points: A Brief History of Ukraine.

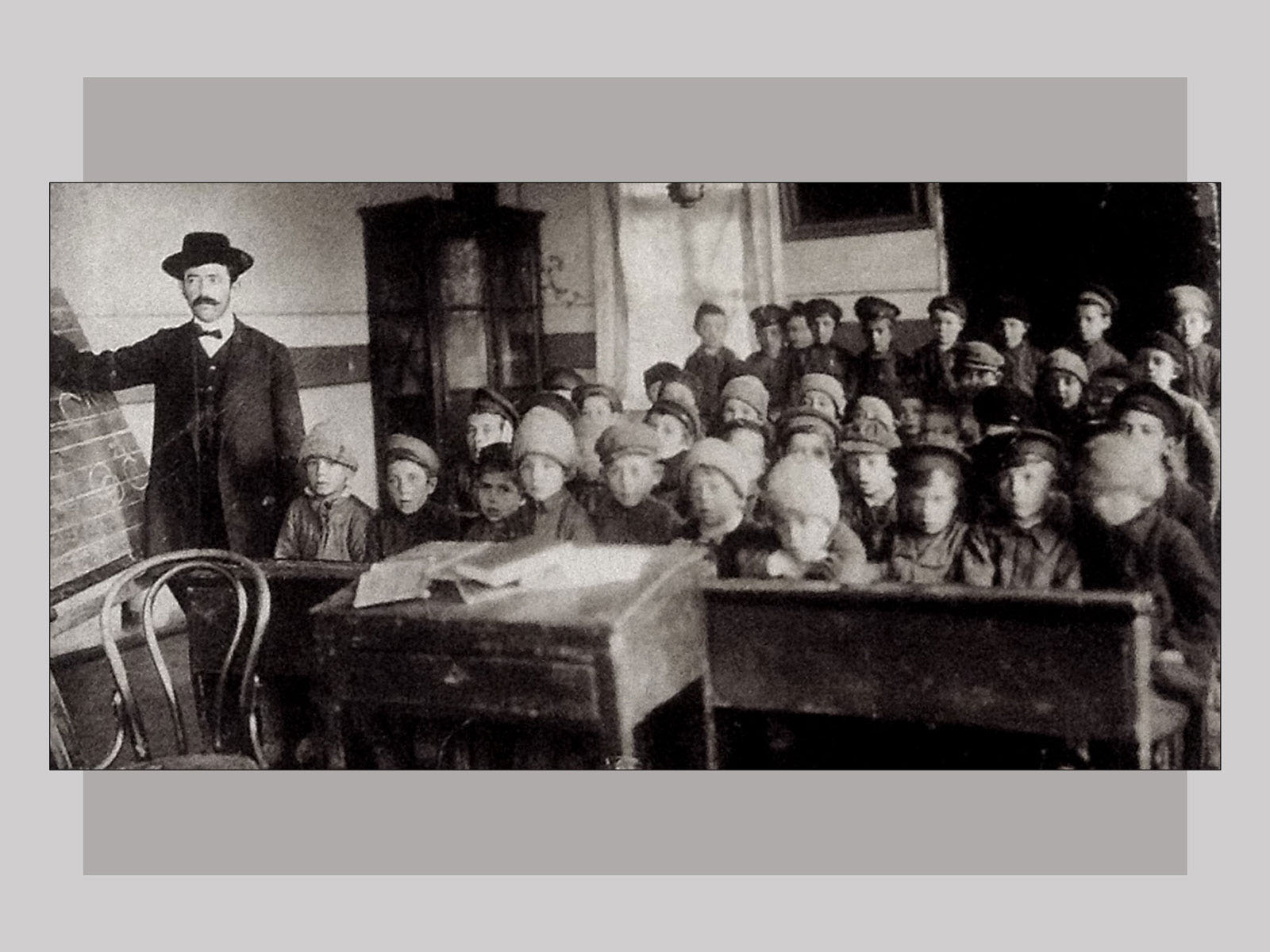

1841–1844

Count Sergey Uvarov, Minister of Education of the Russian Empire, hired Max Lilienthal to serve as his special adviser for Jewish affairs after learning about the successful modern school for Jewish children that Lilienthal had established in Riga. Lilienthal's mission was to replicate the Riga school throughout the Pale of Settlement as part of Uvarov’s plan to “enlighten” the Jews of Russia by introducing them to secular studies and preparing them for productive employment.

Read more...

Though the plan faced severe opposition from senior governmental authorities, Uvarov persisted. Lilienthal's mission also encountered vehement opposition from traditional Jews who viewed it as an attempt by the government to undermine Jewish religious education and incline Jews to convert to Russian Orthodoxy. Many proponents of the Haskalah also did not support the project because they were critical of Lilienthal's weak knowledge of Hebrew and suspicious of his background as a German-Jewish reformer. Lilienthal further alienated Jewish community leaders by advocating the legal enforcement of educational reform on Jews.

Recent scholarship considers that Uvarov’s plan was not aimed at proselytizing but was part of his overall goal to introduce Western-style and classical education throughout the Russian Empire. Despite the opposition, Uvarov issued a law in 1844, calling for the creation of a network of state-sponsored schools for Jewish children throughout the Pale. For his part, Lilienthal abandoned the project and left for Germany and from there to the United States, where eventually he became the rabbi of a prominent Reform congregation in Cincinnati.

Though the state schools for Jewish children had limited enrolment, they continued to function and influence the Russification of segments of the Jewish population for decades to come.

sources

- Michael Stanislawski, "Lilienthal, Max," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1844–1900s

The Russian state established special schools for Jewish children, determined to teach them Russian and basic secular subjects. The maskilim hailed from these schools and administered them, but the traditionalist majority feared and hated them. A model for such schools was the first modern Jewish school established in Odesa in 1826 by the Galician maskil Bezalel Stern.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. I, 367;

- Michael Stanislawski, "Russia: Russian Empire," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

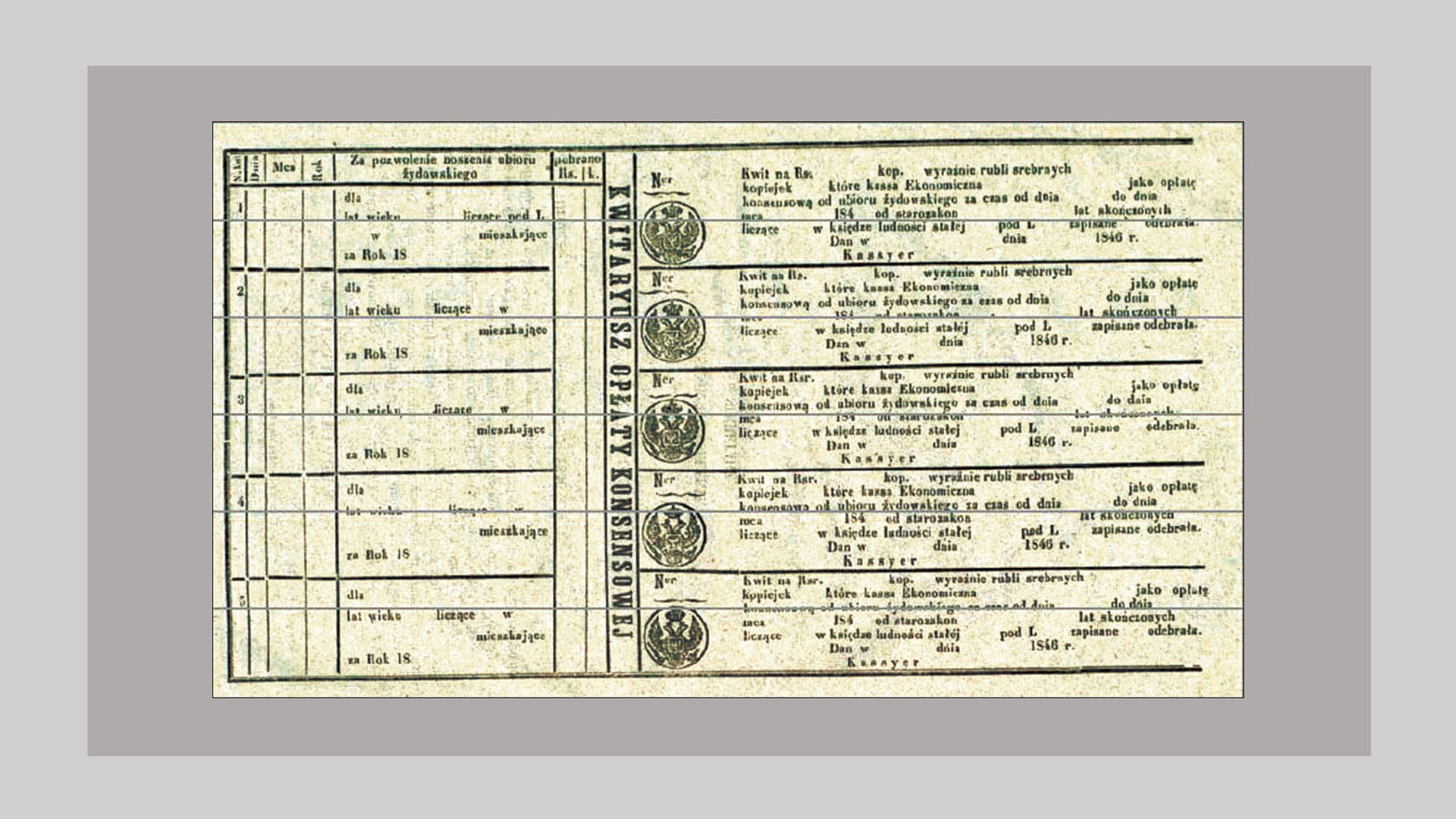

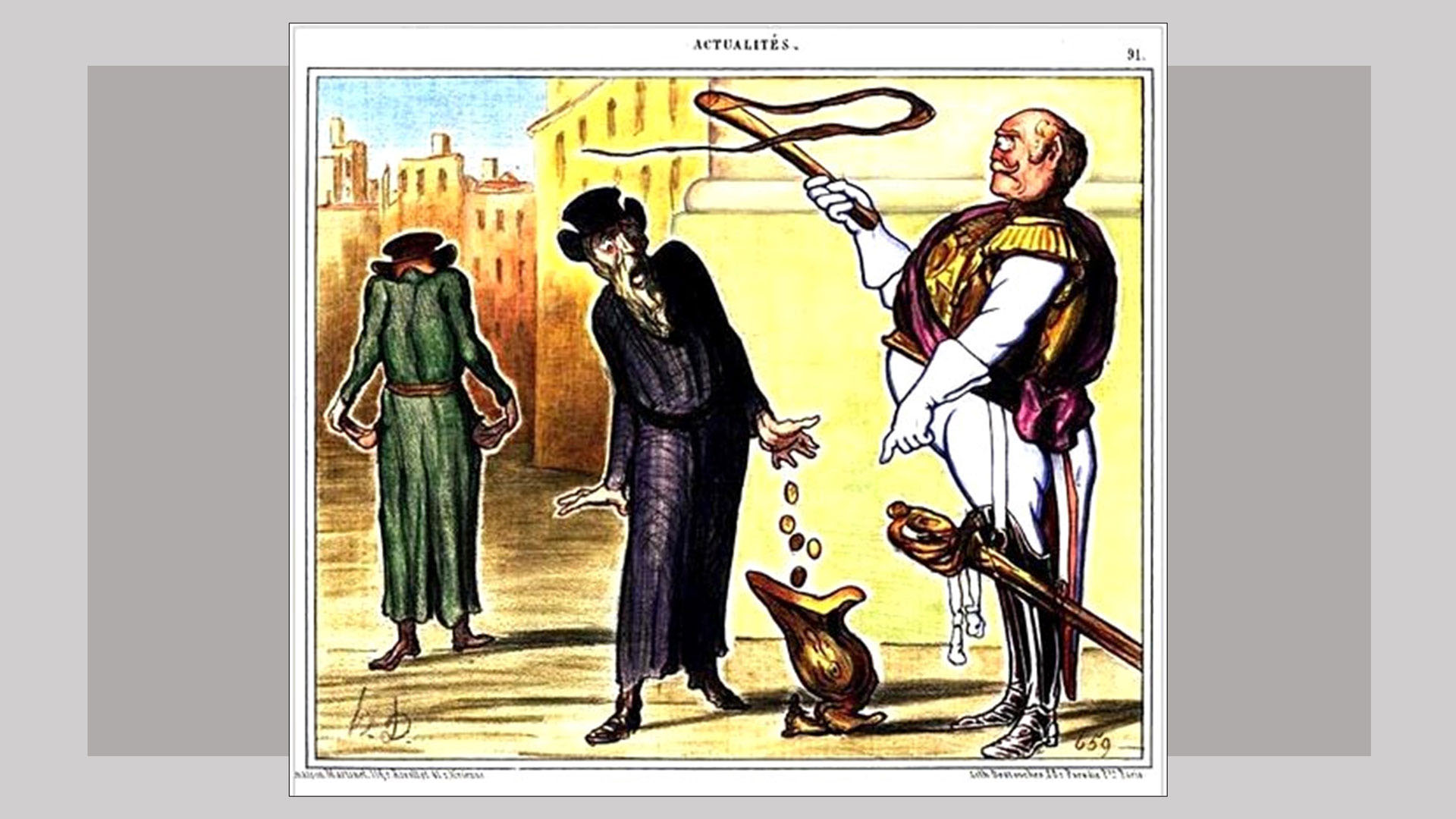

1846

The government enacted a comprehensive set of decrees imposing special taxes on Jews and banning traditional Jewish dress. The decrees were enforced by fines, and occasionally, acts of public humiliation. The Jewish philanthropist Jacob Joseph Halpern of Berdychiv donated one thousand rubles to help pay the tax on wearing yarmulkes (kippahs or skull caps) for the poorer Jews.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. I, 383–84.

1847

The government established two state rabbinical seminaries in the Russian empire, one in Vilna and one in Zhytomyr. Their mission was to provide training for rabbis and produce educated laymen who would transform Russian Jewish life. As observed by one alumnus, every student in these schools "regarded himself as no less than a future reformer, a new Mendelssohn."

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. I, 376–77.

1850s

A new ideology crystallized among the Karaites in the Crimea, primarily due to the Karaite spiritual leader Avraam Firkovich. Born in Lutsk (Volhynia), Firkovich then lived in Lithuania before settling in Chufut-Kale, Crimea. Firkovich and his followers re-interpreted Karaite ethnic and cultural history, gradually erasing most Jewish elements from the Karaite heritage.

sources

- Golda Akhiezer, "Karaites" and "Firkovich, Avraam Samuilovich," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1854–1865

Abram Iakov Bruk-Brezovskii founded a private Jewish girls' school in Kherson in 1854, one of the first modern educational institutions for women in the Russian Empire. He believed that "in the education of women is included the source of education for the whole people: in their hands rests the fate of the next generation."

Read more...

Iosef Khones, a former government Jewish schoolteacher, founded another private school for Jewish girls in Kherson in the mid-1850s. In 1865 he closed his school and immediately opened a mixed-religion private school for girls, with the approval of local authorities. Of the 120 girls in his new school, 60 were Jewish. His success in promptly enrolling such a large number of students in a religiously mixed educational setting suggests that he was addressing an unmet need among local non-Jewish girls as well.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. II, 346;

- Eliyana R. Adler, In Her Hands: The Education of Jewish Girls in Tsarist Russia (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2010), 136.

1859

Khane-Rokhl Verbermakher (1806? –1892), "Di Ludmirer Moyd" (the Maiden of Ludmir), the only female to become a Hasidic leader, emigrated from the Volhynian town of Volodymyr-Volynsky (Yid.: Ludmir) to Palestine. Legends abound about her life as an only child of a well-to-do widower who gave his daughter a good education, her mystical experience after a fall near her mother's grave, her connection with the Hasidic tsaddik Mordekhai of Chornobyl, and the impact of a visit to a Uniate convent. More enduring are stories about her reputation as a Torah scholar who acquired a large following as a teacher, visionary preacher, healer, and miracle worker. While the town's prosperous Jews supported the chief rabbi Moshe and his large choral synagogue, the poorer Jews flocked to hear the Maiden's sermons. However, her unusual activities and behaviour, especially her refusal to marry and observance of religious rituals traditionally reserved for men, aroused controversy and opposition. It appears that in Jerusalem, she re-established herself as a holy woman, though factual evidence about her life during these years (or before) is minimal. Recent research has confirmed that she is buried on the Mount of Olives.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. II, 344–345;

- Ada Rapoport-Albert, Female Bodies, Male Souls (Oxford and Portland, OR, 2018);

- Volodymyr Muzychenko, Jewish Ludmir: The History and Tragedy of the Jewish Community of Volodymyr-Volinsky (Boston, 2016), 35–42.

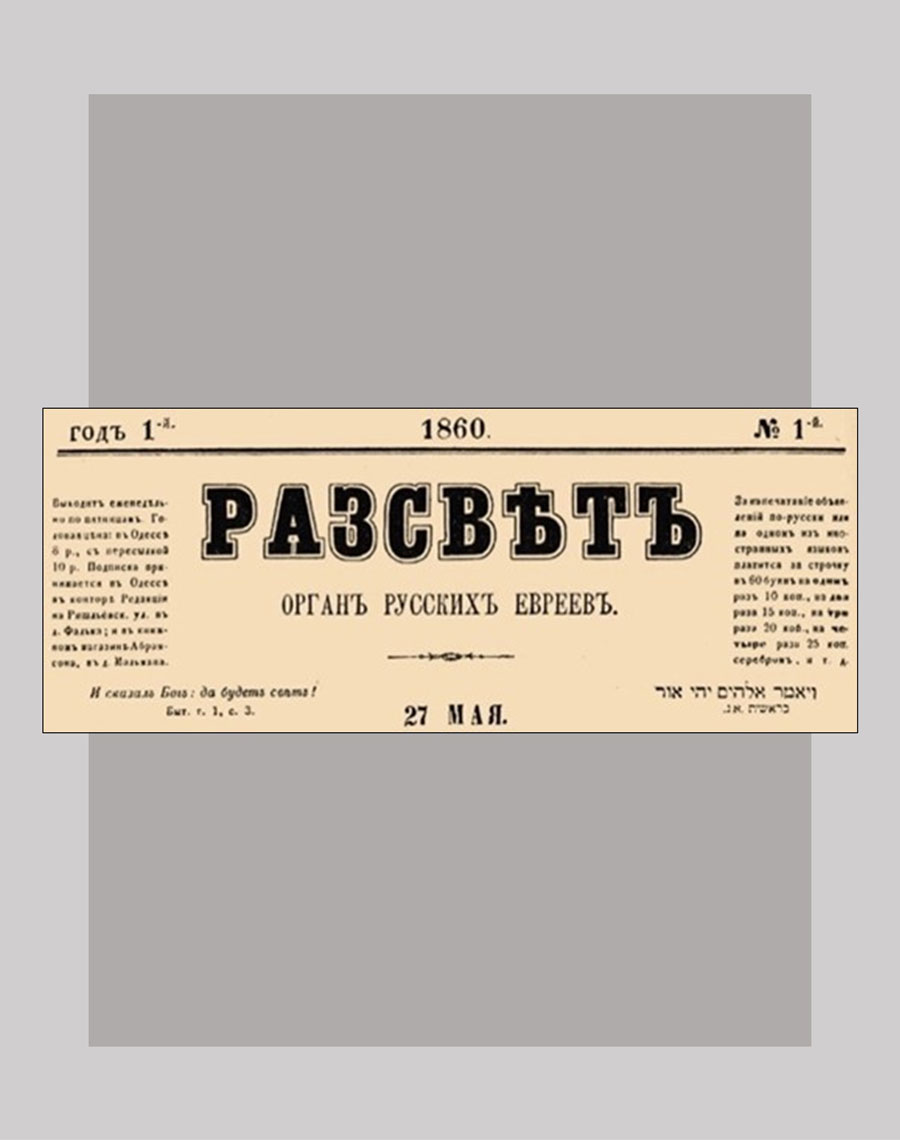

1860

Razsvet (Dawn), a Russian-language Jewish newspaper, was launched in Odesa by Osip Rabinovich with a dual goal — to inform the general public about the nature of Jewish society and to advocate for their civil rights. Rabinovich came from a Russified family and studied at Kharkiv University before becoming a notary in Odesa. In 1858 he published the compelling article "O Moshkakh i Ioshkakh" in Odesskii vestnik, a leading Odesa newspaper, encouraging Jews to recover their dignity and stop using the diminutive names they had once adopted to please Polish landlords. Rabinovich was also a fiction writer; two of his works addressed the difficult experience of Jews in the tsarist army. In Razsvet, which Rabinovich edited until it was closed by government order in May 1861, he continued to criticize Jewish traditionalism while defending Jews against injustice and Russian society's anti-Jewish prejudices.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. I, 409, 416;

- Gabriella Safran, "Rabinovich, Osip Aronovich," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

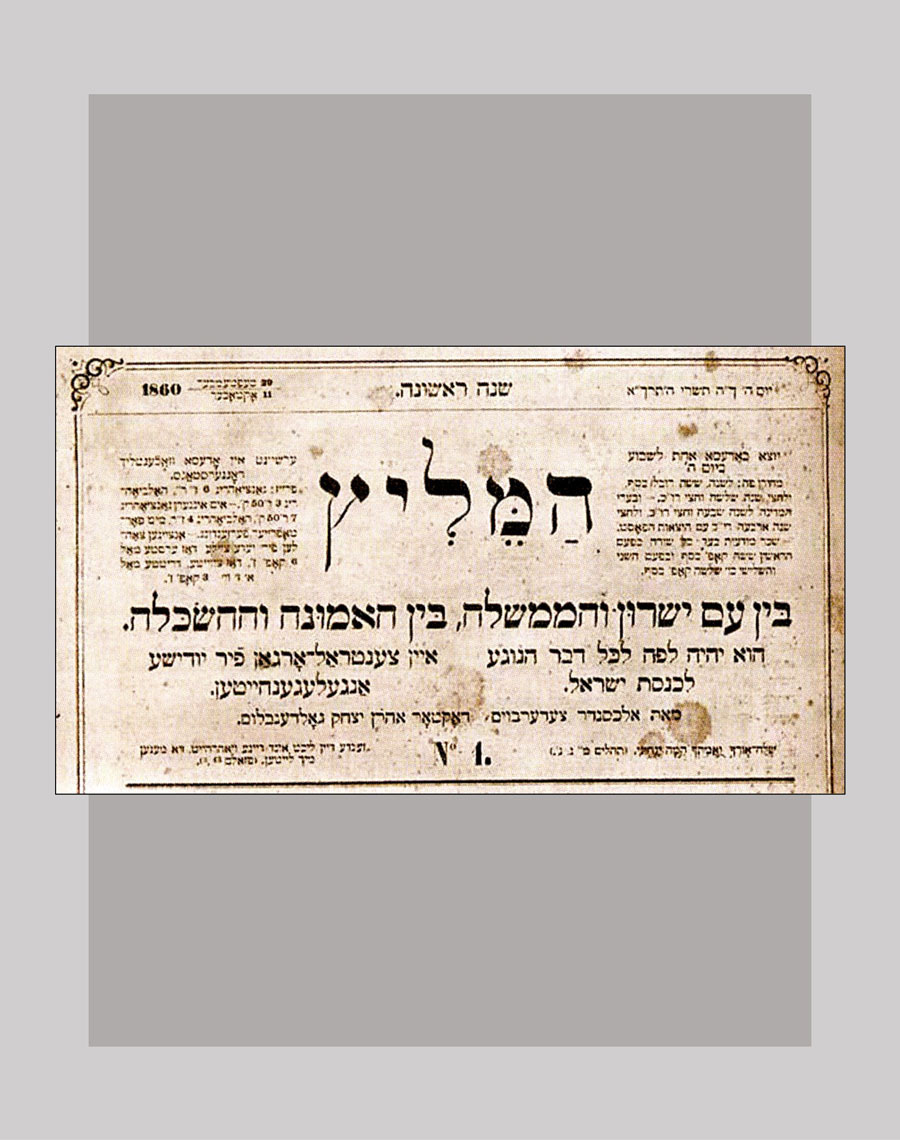

1860–1904

Ha-Melits, the first Hebrew-language weekly in tsarist Russia, was published in Odesa from 1860 to 1870 and then in Saint Petersburg until 1904. Its founder and editor-in-chief during most of its years was Aleksander Zederbaum. Its financial support came from the Society for the Promotion of Culture among the Jews of Russia.

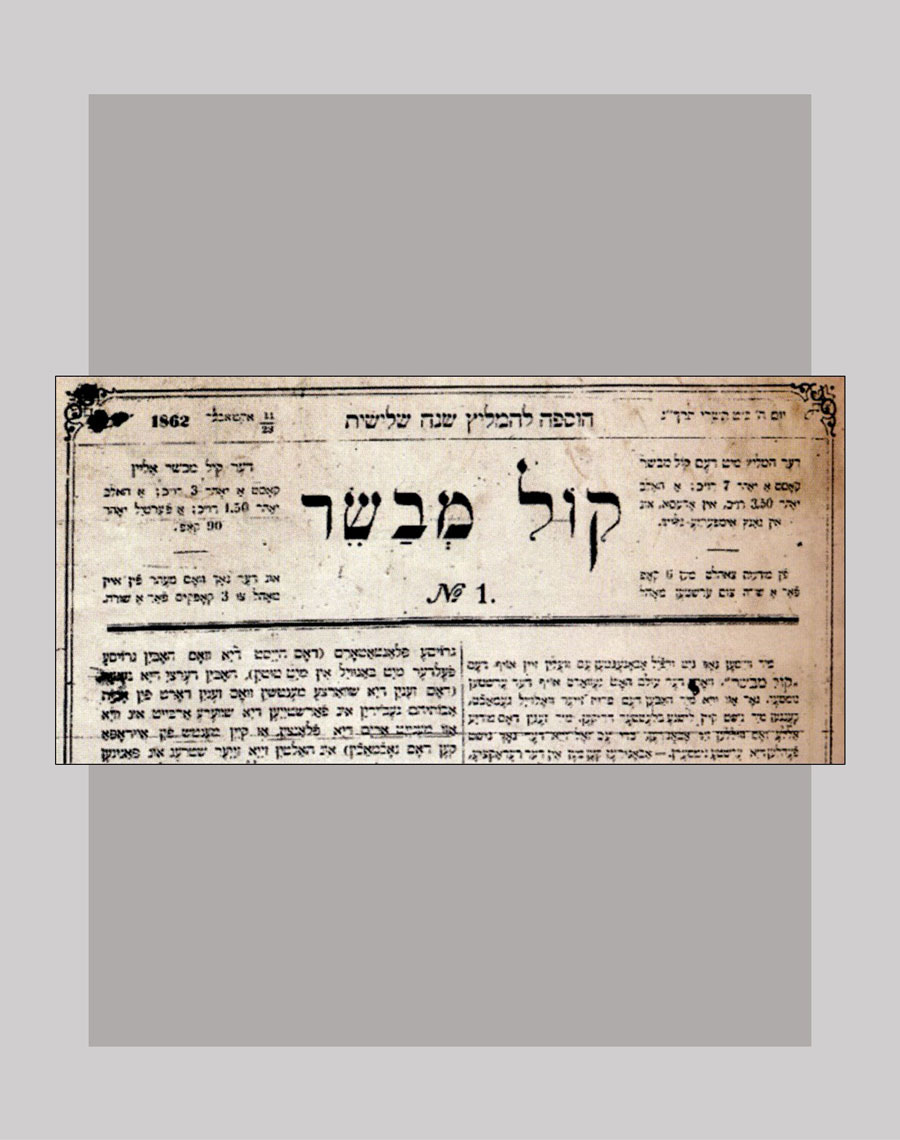

In 1862, Zederbaum introduced Kol Mevasser, a Yiddish-language supplement to Ha-Melits. The editors and journalists of this popular publication "in the spoken tongue" attempted to standardize the spelling of Yiddish and to create a written Yiddish more closely aligned with the spoken language, initially in the dialect of Volhynia.

Read more...

Kol Mevasser contributed significantly to the emergence of modern Yiddish popular literature, as many works first appeared in the form of serialized novels on its pages. This weekly supplement also treated social problems and was noted for attracting many women readers. The weekly publication was discontinued in 1873, likely because Zederbaum was not able to obtain permission to publish it in Saint Petersburg.

Several aspirations shaped Zederbaum's editorial policies. In the first decades, he hoped to advance the integration of Jews into Russian society in accordance with the vision of the Haskalah movement. At the same time, he sought to mediate between the diverse sectors within the Jewish population (religious and secular, traditional and modernist) and between Jews and the Russian government. The latter purpose may explain why he relocated from Odesa to Saint Petersburg in 1871.

Following the 1881–1882 pogroms, the Hebrew-language Ha-Melits analyzed and countered articles published in the antisemitic Russian press and increasingly associated itself with the platform of the Hibat Tsiyon (Love of Zion) movement. Ha-Melits, which became a daily in 1886, endured periodic repression by Russian censors. It ceased publication in 1904, likely because it lost readers to the growing number of Jewish publications in Yiddish and Russian.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. II, 225–227;

- Oded Menda-Levy, "Zederbaum, Aleksander," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010);

- Avraham Greenbaum, "Newspapers and Periodicals," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

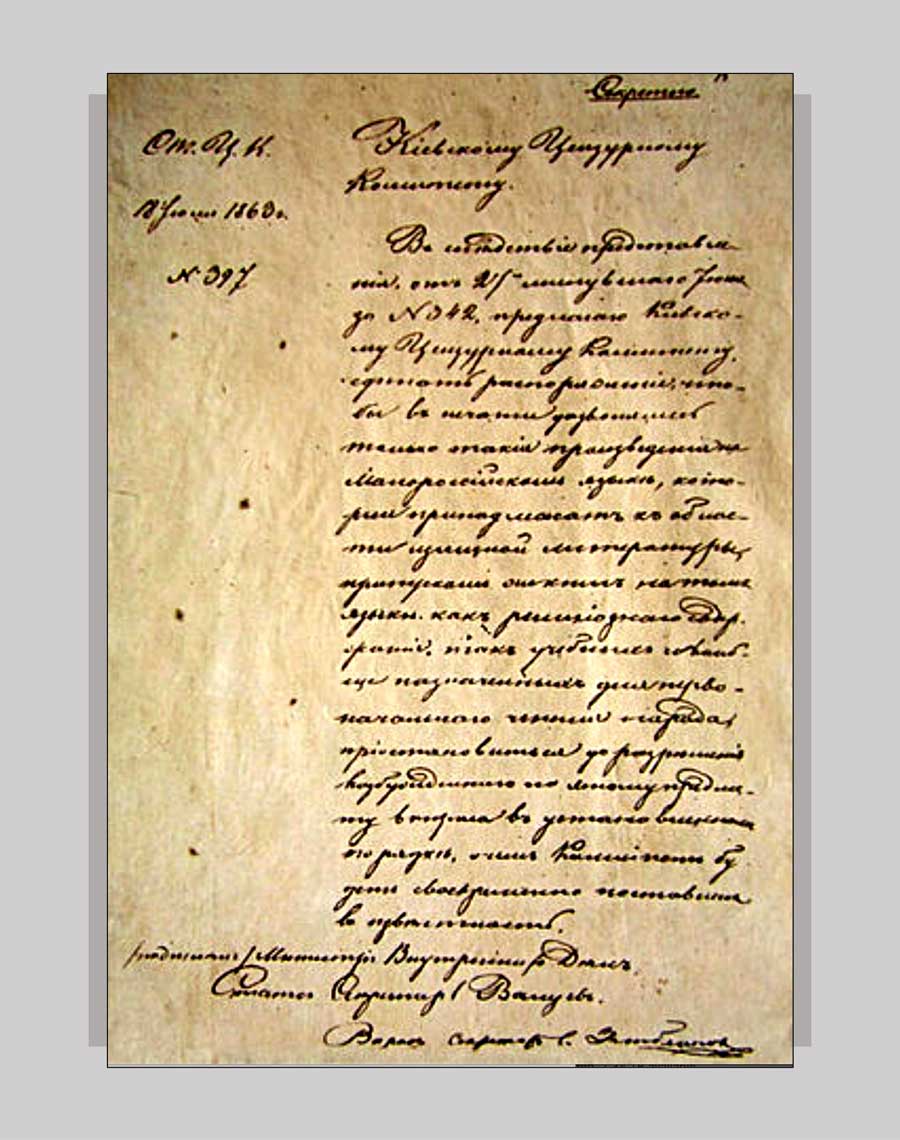

1863

The Russian Minister of the Interior, Count Petr Valuev, issued a decree banning the publication of religious and educational books in Ukrainian. The decree followed a rejection by the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church of a Ukrainian translation of parts of the New Testament. The grounds for the rejection was that such translation into a legally non-existent language was politically dangerous. The decree aimed to end the Russian vs. Little Russian debate with the unmistakable message that there is no Little Russian or Ukrainian language and that those who believed otherwise represented a minority and, likely, an anti-imperial separatist minority. A secret imperial decree in 1876, the Ems Ukaz, reinforced the ban with even more severe anti-Ukrainian measures.

sources and related

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 393–94.

- John-Paul Himka, Ten Turning Points: A Brief History of Ukraine.

Related

Chapter 6.4 1876 (Ems Ukase)

1863

The Society for the Promotion of the Enlightenment among the Jews of Russia was established, with one of its main branches in Odesa. The Society had two main goals: defending Jews against unjust accusations and advocating for Jewish causes; and advancing knowledge of the outside world by encouraging modern education among the Jews, especially in the Russian language.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. I, 420.

1860s–1900s

Four new Jewish literary cultures emerged during this period. The first is the Haskalah-inspired Hebrew literary renaissance in Odesa, which included the works of the eminent Hebrew poet of the modern period, Haim Nahman Bialik. The second is the Yiddish literary movement that attracted intellectuals of a populist orientation, represented by its founders Mendele Moykher-Sforim (Sholem Yankev Abramovitsh), the preeminent humorist author Sholem Aleichem (Sholem Rabinowitz), and the celebrated writer Yehuda Leib Peretz. The third and fourth were the Russian-Jewish and Polish-Jewish literary cultures that responded to the needs of a growing number of acculturated or assimilated Jews, inspired by liberal political movements and the struggle for the emancipation of Jews and other minorities.

sources and related

- Michael Stanislawski, "Russia: Russian Empire," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

Related

Chapter 6.4 1865 (Mendele Moykher-Sforim)

Chapter 6.4 1894–1911 (Sholem Aleichem)

Chapter 6.4 1903 (Hayim Nahman Bialik)

1860s–1900s

Millions of Jews in the Russian Empire began to speak Russian and became consumers of Russian culture after attending government-run Russian-language primary and secondary schools and universities (to the extent that quotas permitted). Linguistic acculturation naturally paralleled upward socioeconomic mobility and was frequently accompanied by politicization. In the Polish provinces of the empire, a similar process of Polonization took hold among Jews. The result was the emergence of a Russian-speaking and, to a lesser extent, Polish-speaking Jewish intelligentsia. Maskilim and graduates of the modernized Jewish school system also became part of the Jewish intelligentsia.

sources

- Michael Stanislawski, "Russia: Russian Empire," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

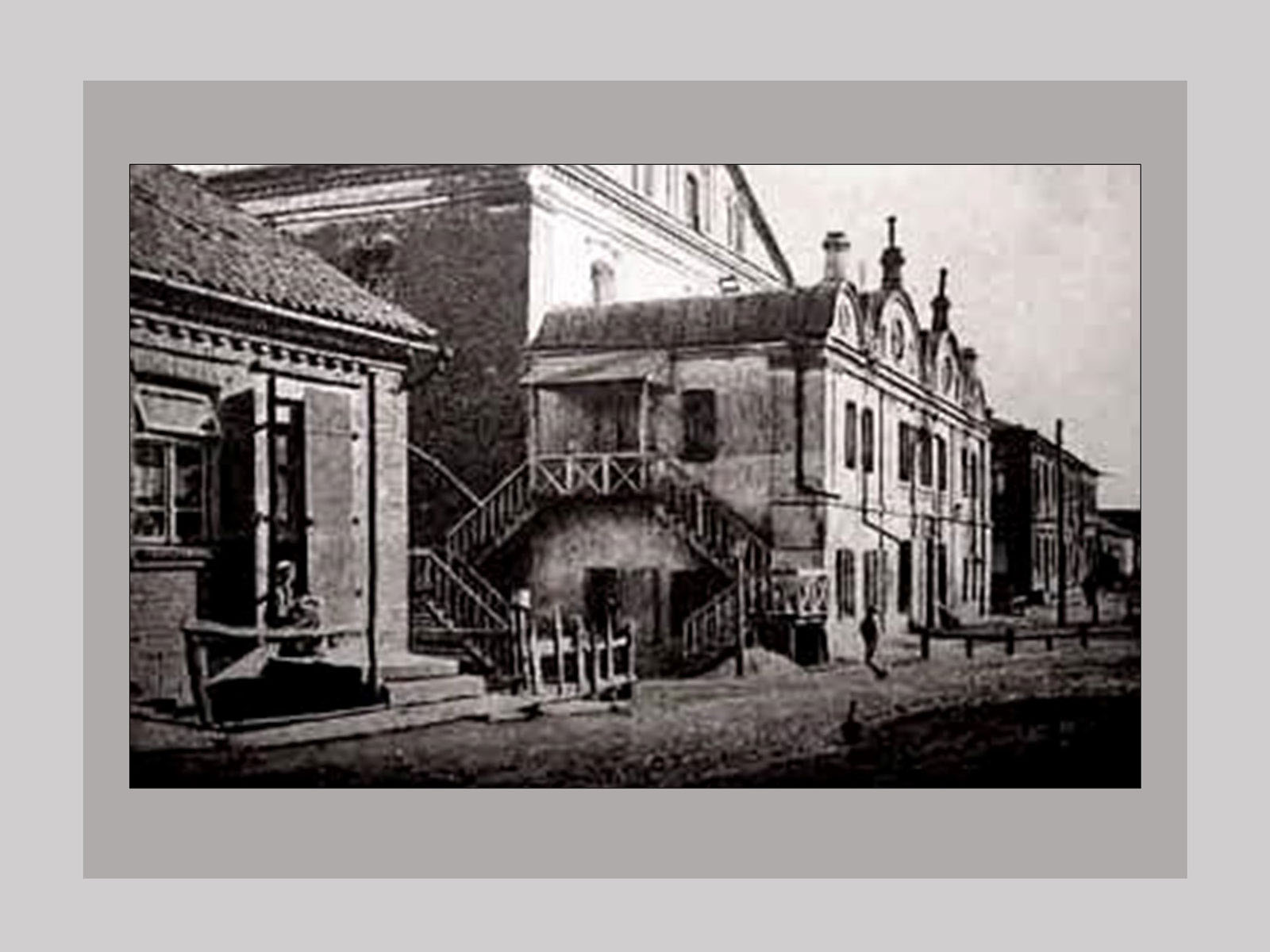

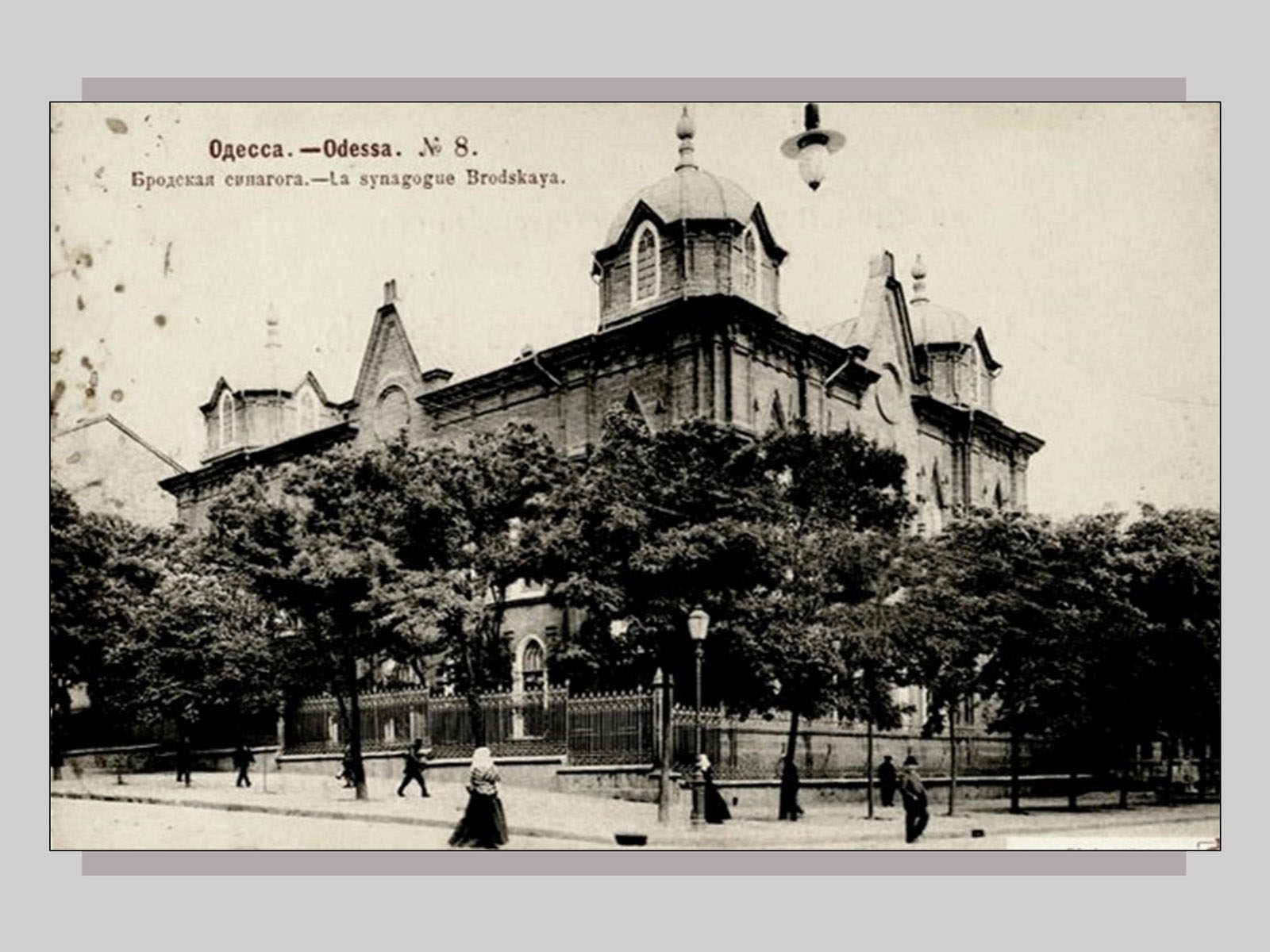

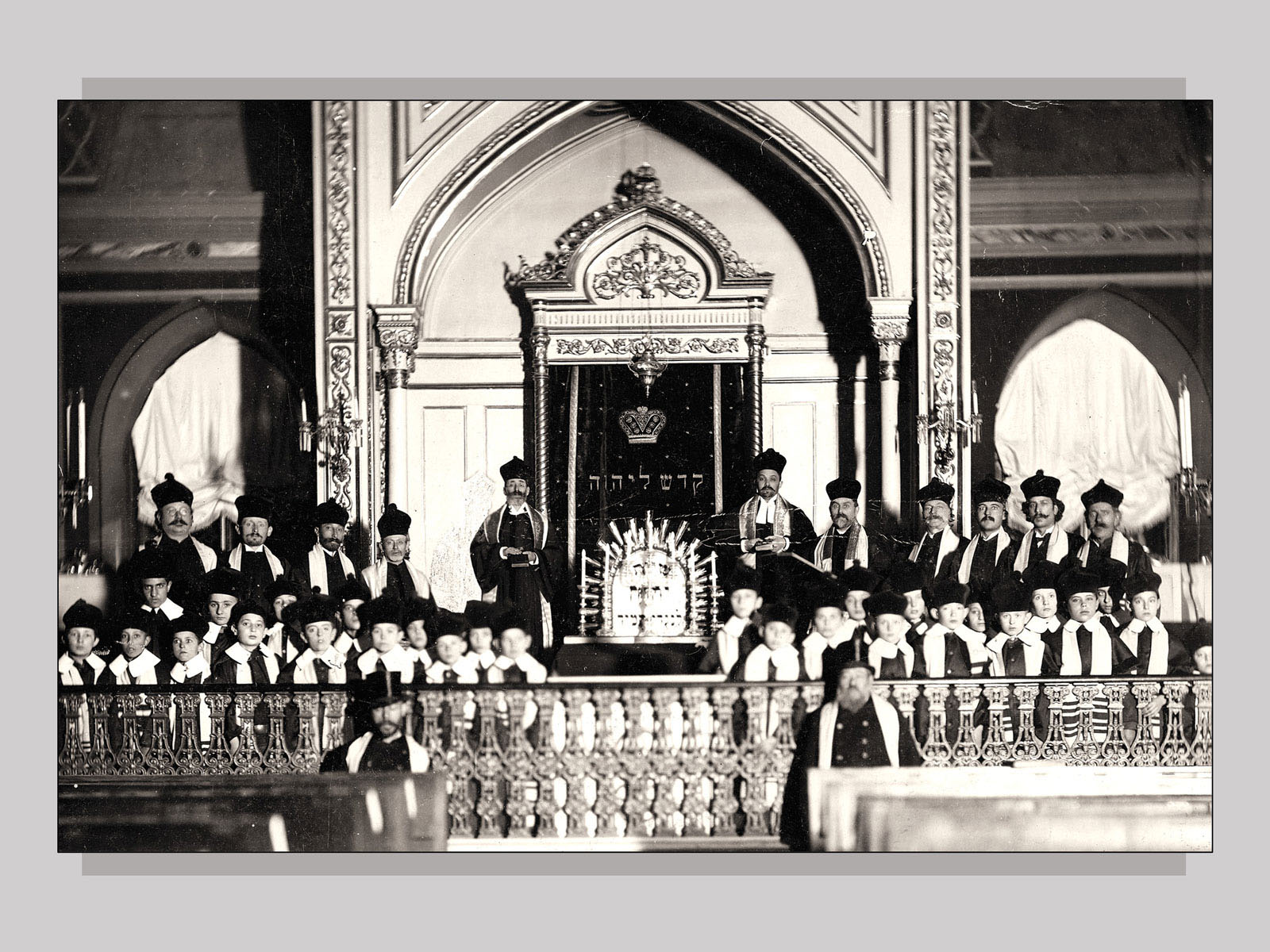

1840–1909

In 1840 a group of well-to-do merchants, originally from the town of Brody in Galicia, established the modernist Brody (Brodsky) Choral Synagogue in Odesa — the first progressive (but not fully Reform) synagogue in the Russian Empire. The services in this synagogue included an excellent choir. They were more orderly and aesthetic than those held in the Beit Knesset Ha-Gadol, the older, community-sponsored modernist synagogue, or in the city's more traditional synagogues. Stung by criticism that its services were noisy, overcrowded, and lacking in decorum, the leaders of Beit Knesset Ha-Gadol raised money for a new and more suitable building. The new building, erected in 1850, included a space allocated for a choir. It also continued to retain its remarkable cantor Bezalel Shulsinger, a renowned composer of numerous influential melodies.

Read more...

In 1860 the Brody synagogue appointed a rabbi from Germany, Dr. Simon Schwabacher, who introduced the practice of celebrating wedding ceremonies within the synagogue building (rather than in the traditional outdoor manner). He also started confirmation ceremonies for girls and gave western-style sermons in German. Negotiations for a merger and rifts between the two modernist synagogues continued for over a decade, culminating in the Brody Synagogue's decision to build its own new structure in 1863. The Brody Synagogue soon became the most prominent synagogue in the city, famous for the musicality of its cantors and choir. By the early 1900s, organ music accompanied its prayer services. More traditionalist Jews, who prayed in five other large synagogues or in the dozens of houses of prayer in the city, naturally opposed the innovations of the modernist synagogues.

Similar modernist choral synagogues (kor-shul in Yiddish) were established in other cities of the Russian Empire. Like Odesa's Brody Synagogue, they followed the model of the German Reform synagogues with a significant difference — the changes they introduced generally related to aesthetics, not to religious beliefs and customs. Features that distinguished the choral synagogues from the traditional ones included preaching in "the language of the country" (initially it was German, later it was Russian), preserving order during the worship, and, above all, the participation of a cantor and a choir in the prayer services.

sources

- Steven J. Zipperstein, The Jews of Odessa: A Cultural History, 1794–1881 (Stanford University Press, 1986), 56–61;

- Michael Beizer, "Religious Reform: An Option For The Jews Of Russia In The First Quarter Of The 20th Century?" Proceedings of the World Congress of Jewish Studies (1997);

- Polin — Virtual Shtetl, "Odessa."

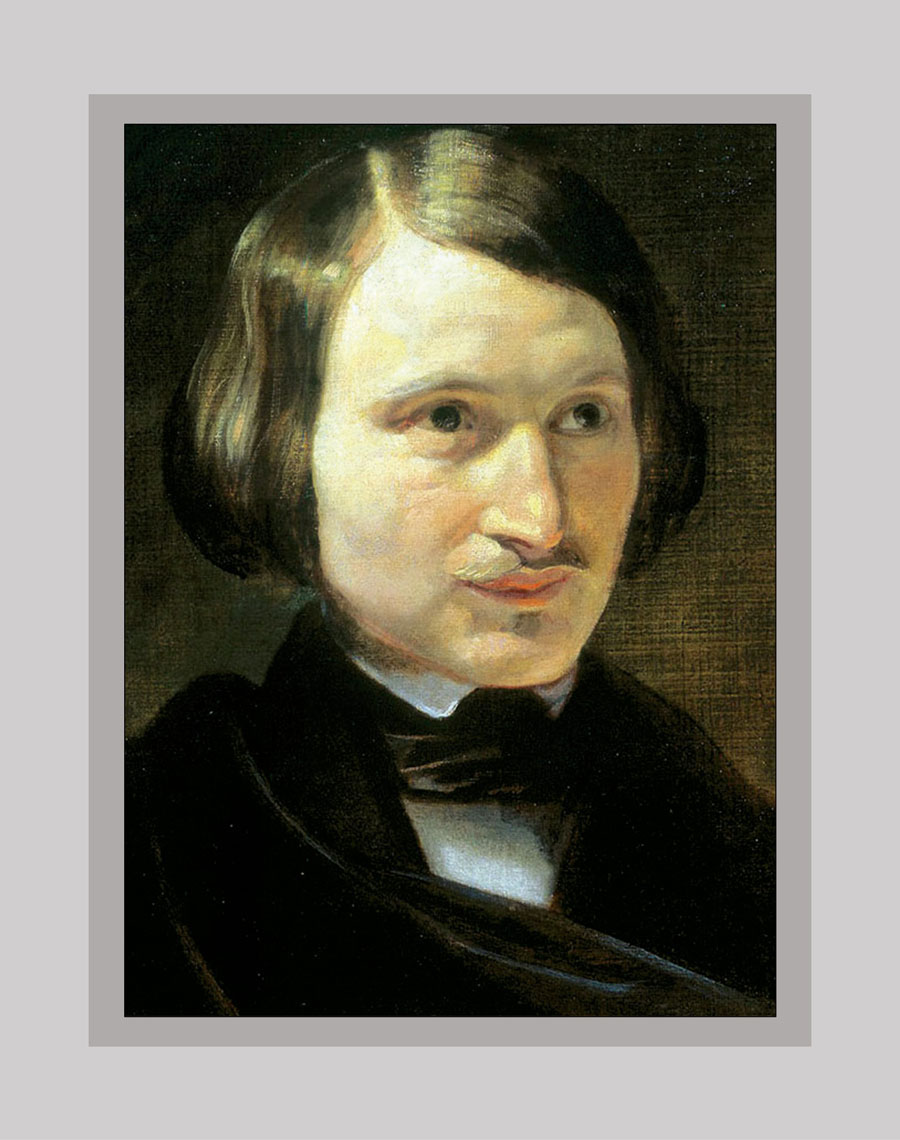

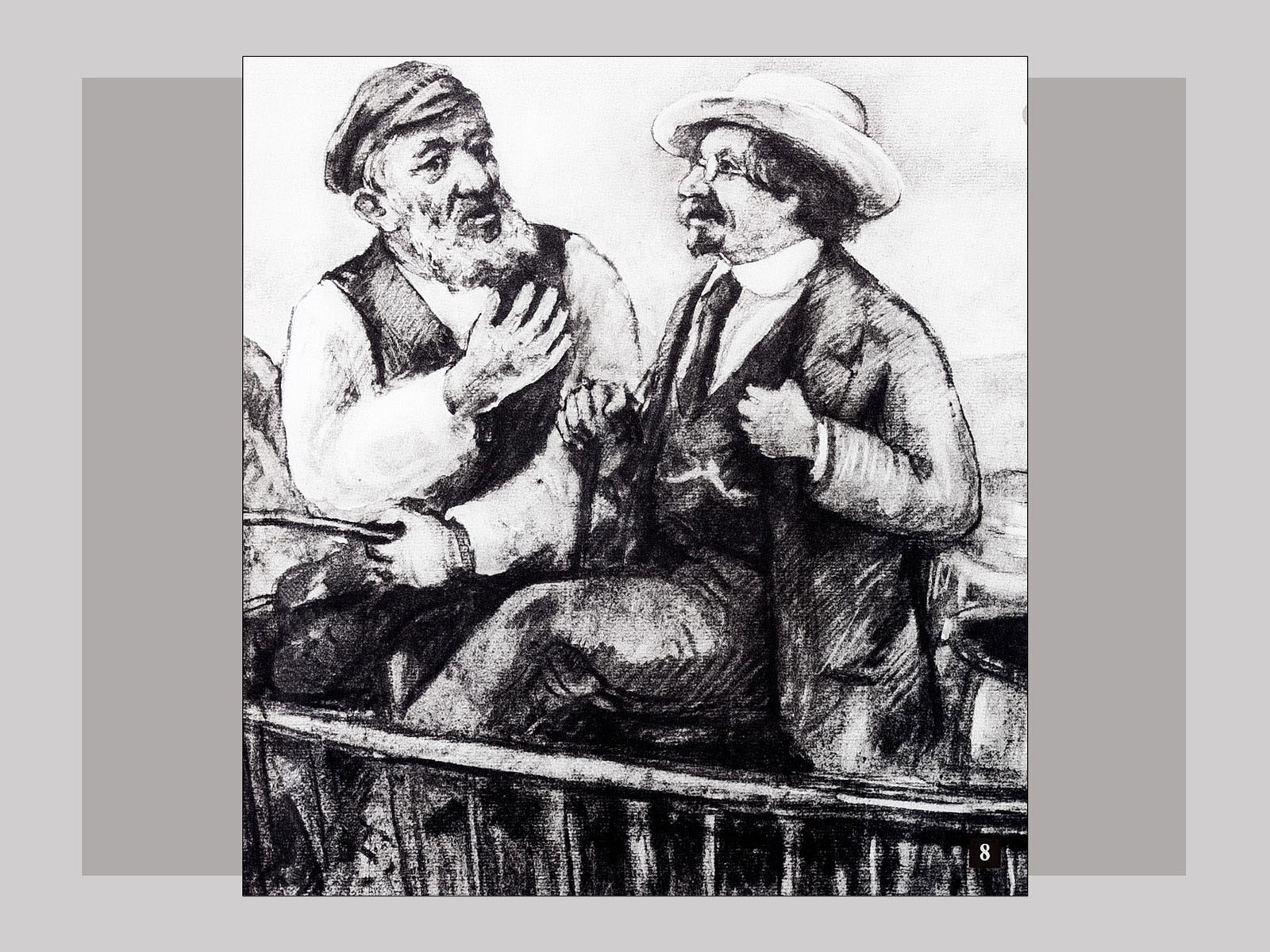

1865

The Yiddish novel Dos kleyne mentshele (The Little Man) by Sholem Yankev Abramovitsh was published, soon making the author's literary persona (and the author's pen name), Mendele Moykher-Sforim, a household name in the Yiddish-speaking world. With this story, Abramovitsh introduced Yiddish, the spoken language of Eastern European Jews, as a literary language on a par with Hebrew. The inspiration for creating the fictional character Mendele, a narrator of many other stories by Abramovitsh, came from Rudyi Panko ("Red-Haired Panko"), a narrator of the Dykanka stories by Nikolai Gogol, the most famous Russian writer of Ukrainian origin and one of Abramovitsh's favourite writers. Both Mendele Moykher-Sforim and Sholem Aleichem — the former dubbed the "grandfather" and the latter the "father" of Yiddish literature — admired Gogol's literary talents, despite the Judeophobic stereotypes contained in his writings.

sources and related

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. II, 239.

Related

Chapter 6.4 1860s–1900s

1869–1878

Ethnographic expeditions in Right-Bank Ukraine in 1869–70, led by Pavlo Chubynsky, produced a wealth of material on Ukrainian dialects, folklore, customs, and folk beliefs. Under the direction of Chubynsky, the Southwestern Branch of the Imperial Russian Geographic Society in Kyiv (founded in 1873) inaugurated a new period in the history of Ukrainian ethnography, as researchers advanced from producing individual publications to the large-scale codification of ethnographic materials and the publication of several large-scale series.

Read more...

Volume 7 of the series entitled The Works of the Ethnographic and Statistical Expedition to the West Russian Land (7 volumes, 1872-1878) was devoted to the socioeconomic and cultural situation of Poles and Jews in Right-Bank Ukraine. It contained valuable statistical information about Jews, but the editor's commentary was not devoid of anti-Jewish motifs regarding the perceived negative economic role of Jews in rural Ukraine.

For his extensive research, Chubynsky was awarded a gold medal by the Russian Geographic Society in 1873, a gold medal at the International Exhibition in Paris in 1875, and the Uvarov Prize by the Russian Academy of Sciences in 1879. Chubynsky also published a collection of poetry, entitled Sopilka (The Reed Pipe, Kyiv 1871) and wrote the words to 'Shche ne vmerla Ukraïna' (Ukraine Has Not Yet Died), later the anthem of the Ukrainian National Republic and of modern Ukraine. Chubynsky's work stimulated a generation of scholars, including Mykhailo Drahomanov, who developed the theory of borrowed and migrating themes and motifs in folklore.

sources

- Petro Odarchenko, "Ethnography" and "Chubynsky, Pavlo," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1984).

1876

Tsar Alexander II issued the Ems Ukase (decree), accepting all the prohibitory measures recommended by a commission appointed a year earlier to investigate "Ukrainophile propaganda in the southern provinces of Russia." The commission's finding was that the "activity of the Ukrainophiles" presented a danger to the state. This finding served as justification for the decree's severe measures prohibiting the publication of all Ukrainian books (including belles lettres), as well as their importation from abroad. The decree also banned plays and public readings in Ukrainian and even the printing of Ukrainian lyrics to musical works.

Read more...

The decree coincided with the closing of Ukrainian organizations and newspapers deemed suspect and the removal of "dangerous" pro-Ukrainian teachers from classrooms, including a young history professor at Kyiv University, Mykhailo Drahomanov. The experience led Drahomanov to emigrate to Switzerland, where he developed the ideological foundations of Ukrainian liberalism and socialism.

The Ems Ukase, which represented a continuation of the repressive anti-Ukrainian 1863 Valuev circular, dealt a crushing blow to the expansion of Ukrainian culture in tsarist Russia. In 1878 at the International Literary Congress in Paris, Drahomanov severely condemned the Ems Ukase and defended the Ukrainian language in his brochure La littérature ukrainienne, proscrite par le gouvernement russe.

sources and related

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 395–97;

- "Ems Ukase," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine;

- Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe (New York, 2015), 362.

Related

Chapter 6.4 1863

1876

Avrom Goldfaden established the first Jewish modern theatre in the Yiddish language in Iași, Romania, and then proceeded to animate Yiddish stage production in many Ukrainian towns and in New York. After Iași, he collaborated with the famous "Broder zingers" (from Brody) and toured with his company across the Pale of Settlement. He then moved to Odesa, where he founded the Mariinsky Yiddish theatre and composed and produced a large corpus of works for the stage, including musicals, vaudeville and burlesque, as well as epic and biblical-themed plays.

Read more...

After 1883, when tsarist policy undermined Yiddish theatre in Russia, Goldfaden wandered across Europe and America. He settled in Lviv/Lemberg, where he served as director of a Yiddish theatre in 1894–1895. One of his most ambitious productions was Meshiekh's tsaytn?! ("Messianic Times?!"), a panorama in time and space of East European Jewry from a Ukrainian shtetl to Kyiv, New York, and Palestine. Goldfaden's numerous operettas contributed to the Yiddish popular song repertoire; his most famous song, based in part on a folk melody, is the lullaby "Rozhinkes mit Mandlen" (Raisins and Almonds). In 1903, Goldfaden returned to America, where he lived in poverty. More than 100,000 people attended his funeral in New York City.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. II, 390–394;

- "Goldfadn, Avrom" by Seth L. Wolitz and "Songs and Songwriters" by Robert A. Rothstein, YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1881–1900s

The Russian government granted Ukrainians permission in 1881 to create travelling theatres. It was almost the only form of Ukrainian cultural expression permitted in the empire. However, these theatres were banned from performing in Kyiv and a number of regions; ironically, they could perform in St. Petersburg and Moscow as long as the performances stayed within the bounds of (in Myroslav Shkandrij's words) "charming ethnographic curiosities." Restrictions were imposed on topics treated, and certain conditions applied. For example, middle- and upper-class characters were to speak in Russian, Ukrainian was to be depicted as a folk culture, and a Ukrainian-language play could be staged only if a Russian-language play of the same length preceded it the same night. Despite these conditions, amateur Ukrainian theatre groups proliferated in towns and villages across Ukraine in the following decades. How were Jews depicted in these plays?

Read more...

Some earlier plays contained typical, negative stereotypes of the Jewish orendar (leaseholder) and Jewish tavernkeeper. A later play by Mykhailo Starytsky, Iurko Dovbysh (1888, 1910), offered a sympathetic portrayal of a Jewish tavern-keeping family. This play was inspired by stories from Ukrainian and Jewish folklore, which describe a friendly relationship between the legendary outlaw Dovbush and the legendary founder of Hasidism, the Ba'al Shem Tov. Popular plays, such as this one, were often intended for both Ukrainian and Jewish audiences, especially when performed by travelling troupes.

The travelling theatrical troupes, both Ukrainian and Jewish, were immensely popular. Jews in the shtetls flocked to see not only the Yiddish plays but also the Ukrainian theatrical performances, which reconstructed a world with which they were very familiar.

sources

- Myroslav Shkandrij, Jews in Ukrainian Literature. Representation and Identity (New Haven, 2009), 58–61;

- Myroslav Shkandrij, “There are problems in Ukraine that are challenging historians, writers, and civil society,” Hadashot, English translation on UJE website, 18 December 2019.

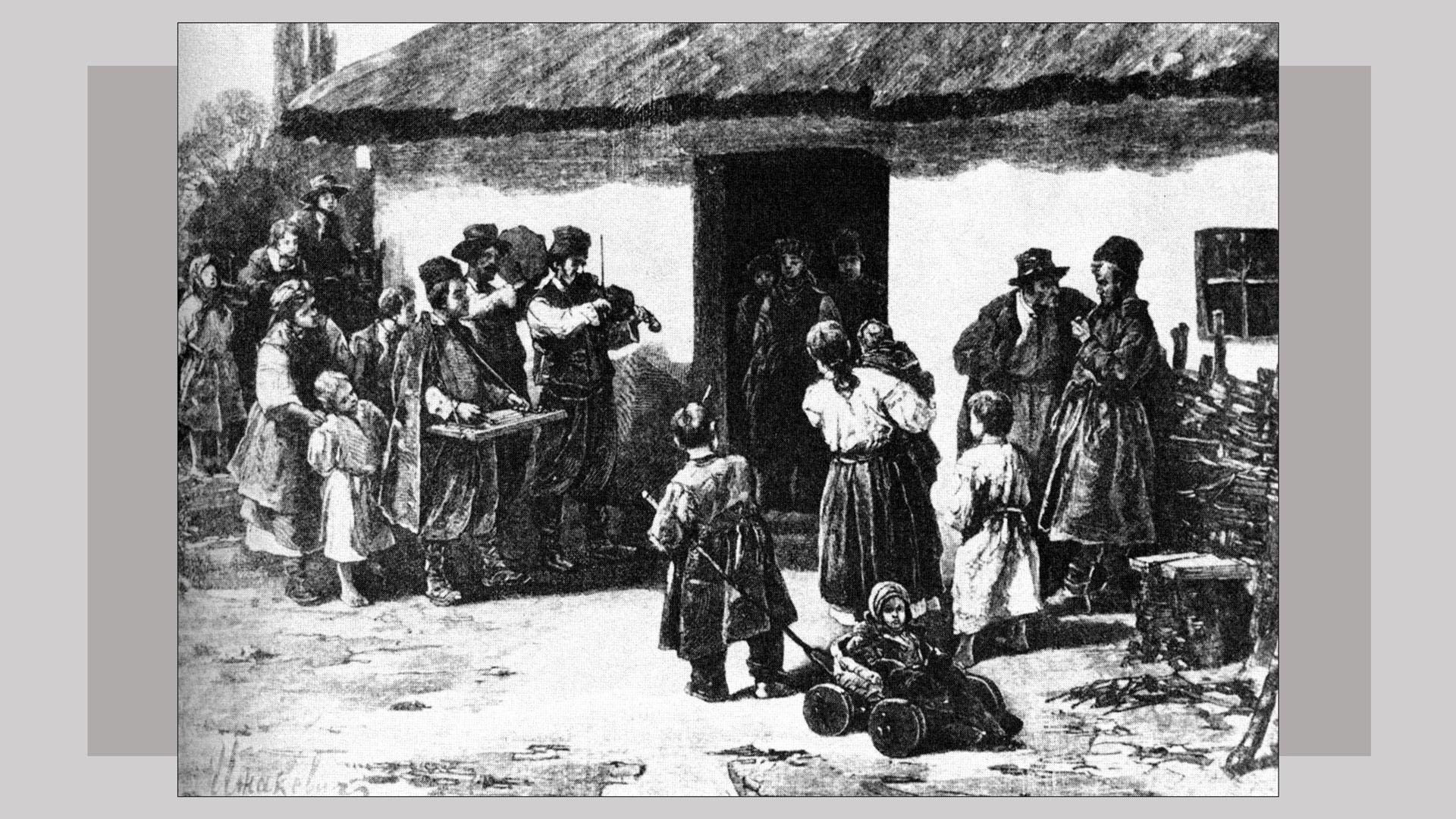

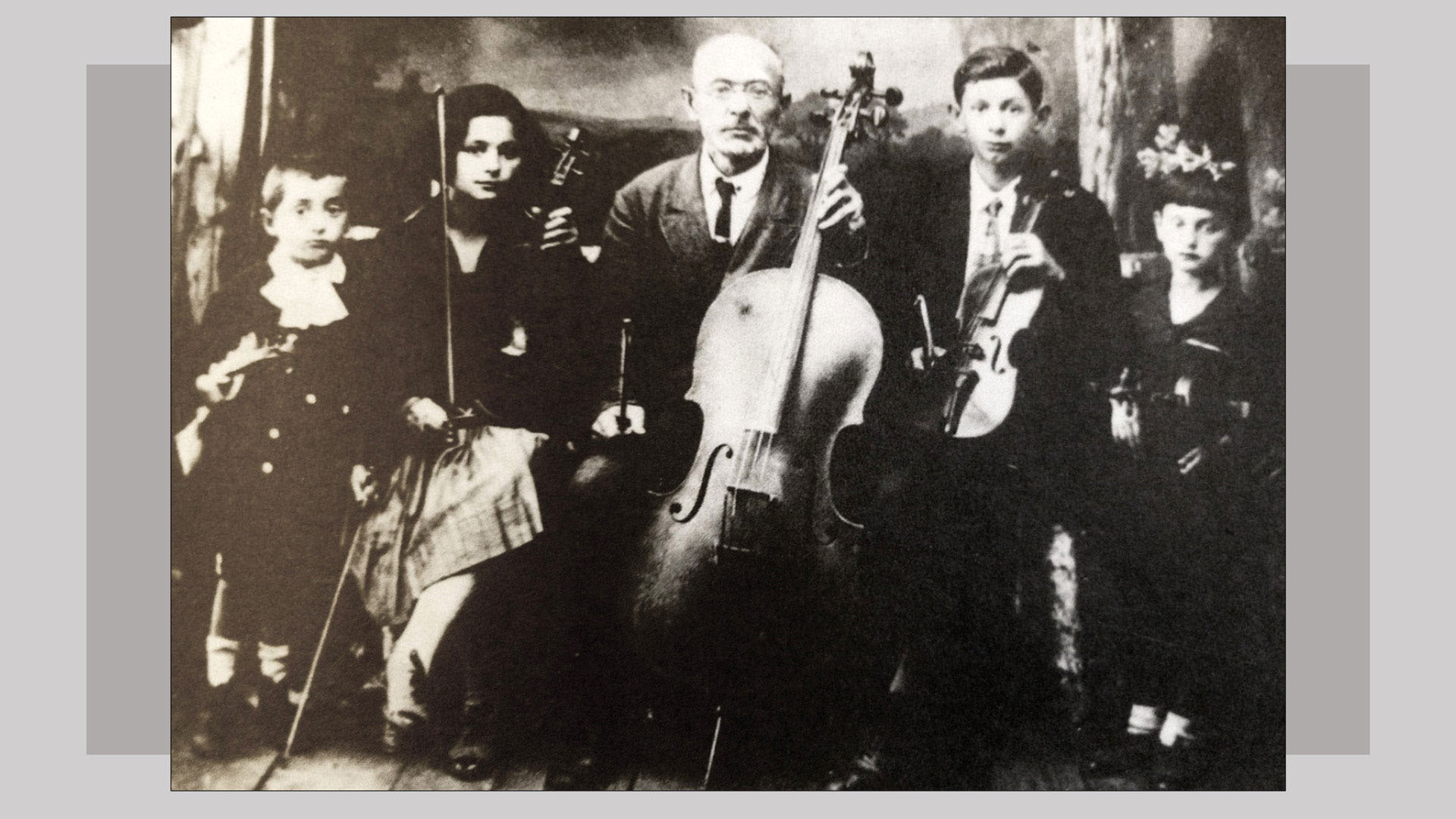

1880s–1900s

Klezmer bands

Klezmer bands proliferated across the Pale of Settlement during this period. The word "klezmer" (from Hebrew, kley zemer, "vessels/instruments of song") refers to a musical genre of East European Jews, played by professional musicians called klezmorim, in ensembles known as kapelye, or larger bands called kompaniya.Their repertoire consisted largely of dance tunes and instrumental pieces, played mostly at weddings.

Read more...

Samples of klezmer music were recorded on wax phonograph cylinders during the 1912–1914 ethnographic expeditions led by S. An-sky in Podilia and Volhynia. (The cylinders, thought to have been lost during the Second World War, were discovered in the Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine in Kyiv in the 1990s.)

The career of bandleader A.Y. Makonovetsky is typical. The son of a klezmorist, he taught himself to play all the klezmer instruments and then formed a group that played not only at Jewish weddings but also at local Ukrainian, German, Czech and Polish weddings. Berdychiv produced several pioneer klezmer musicians. The most famous was Avram Moyshe Kholodenko (1828–1902), known as "Pedotser." An active performer and composer, Pedotser's tunes became common property after his retirement. Another was the itinerant musician Yoysef/Yossele Drucker (1822–1879), known as "Stempenyu," who was the inspiration for Sholem Aleichem's 1889 romantic novel Stempenyu (later transformed into a theatrical production).

The evolution of the klezmer genre illustrates a high degree of Ukrainian-Jewish interaction in the musical domain. Jewish klezmorim knew Ukrainian folk dance music well and played it at both Jewish and non-Jewish weddings and inns. Some klezmer ensembles (especially in Galicia and Bukovina) included Ukrainian musicians. Over time, most peasant string bands in these multi-ethnic regions adopted the klezmer genre. In addition to mutual borrowing, both Jewish and Ukrainian musicians were receptive to common "third source" influences, in particular Moldavian, Romanian, Romani, and Turkic music.

sources

- Walter Zev Feldman, Klezmer: Music, History, and Memory (Oxford, 2016) 26–27, 94, 149–150.

1882–1883

Jewish women made up 15.8 percent of the auditors in women's higher education (equivalent of university) courses in Kyiv.

Two decades earlier, in response to student demonstrations, a statute had been enacted in 1863 banning women from all universities in the Russian Empire. As many women, including Jewish women, were emigrating to study abroad, the authorities in the early 1870s set up special higher education institutions offering courses for women in both the sciences and humanities. Most graduates from these institutions became teachers in state schools; however, Jews were barred from that career.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. II, 354.

1888

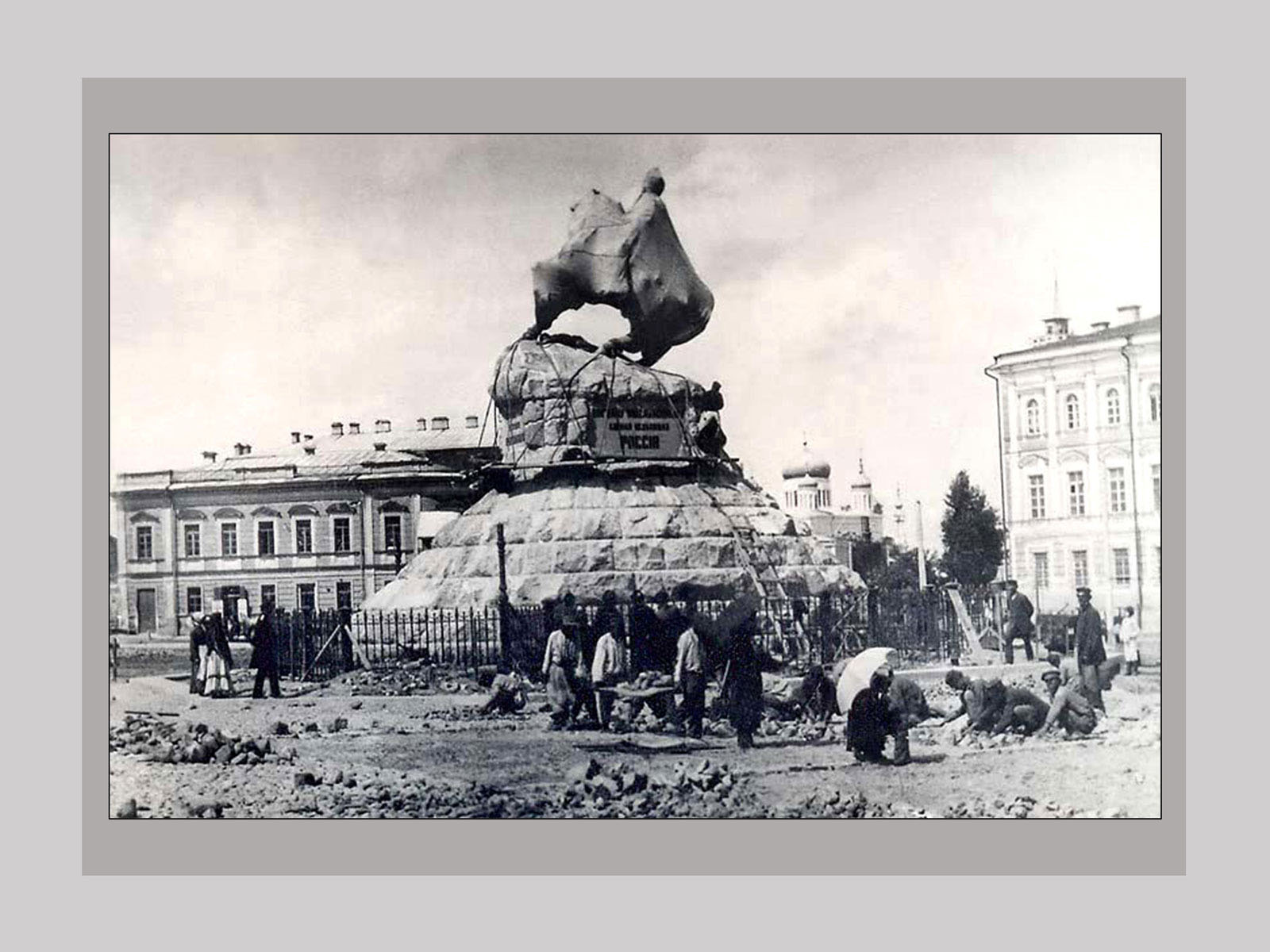

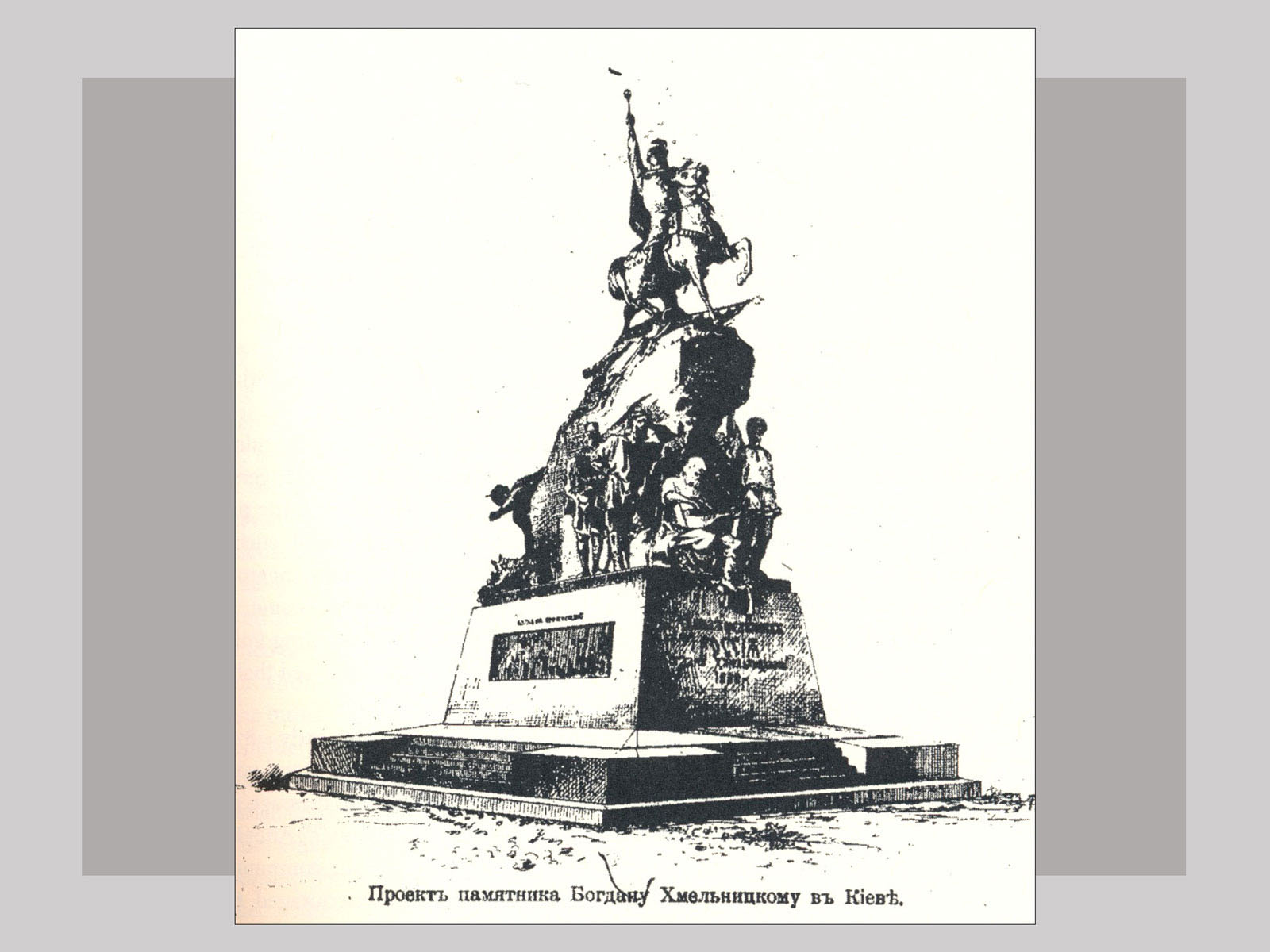

After more than three decades of delays and controversy, a monument dedicated to the Cossack leader Bohdan Khmelnytsky was installed in Kyiv's main square near Sophia Cathedral. The idea of the monument, commissioned by the Russian nationalist and Ukrainophobe Mikhail Yuzefovich, was to present Khmelnytsky as a national hero of Russia for bringing Ukraine into Great Russia. (Note: Yuzefovich was then deputy commissioner of the Kyiv school district and chairman of the Kyiv Archeographic Commission. Years earlier, he was a key member of the imperial commission whose recommendations led to the repressive 1876 Ems Ukase that had severely restricted the use of the Ukrainian language.)

Read more...

The original blueprint and prototype for the monument, prepared by the sculptor M.O. Mikeshin in 1869, featured Khmelnytsky on a horse. Below the horse's hooves were the trampled bodies of (in the artist's words) "the three enemies against whom Khmelnytsky fought so gloriously in Ukraine." These included a Jesuit priest covered by a tattered Polish flag, a Polish noble, and a Jew holding stolen ritual objects and money in his hands. The prototype included additional bas-relief figures — a blind kobzar (itinerant bard) and various ethnic types representing the various "children of Rus'."

On the pedestal supporting the statue, Mikeshin inscribed a traditional folk song, said to date from the seventeenth century: "Oh, it will be better / oh, it will be more beautiful / When in our Ukraine / There are no Jews, no Poles / and no Union" — the latter referring to the Union of Brest which established the Uniate (Greek Catholic) Church.

The blueprint was approved by Tsar Alexander II, the province's Governor-General Dondukov-Korsakov, and the editors of Kievlianin, among others. However, representatives of the Jewish and Catholic communities and members of the Ukrainian intelligentsia and liberal circles objected to these symbols. Some, including the tsar's brother Grand Duke Konstantin, were concerned that such a design would encourage "incitement of national hatred" and the "kindling of anti-social passions." The tsar and the Ministry of Internal Affairs eventually sided with the project's critics and ordered that the figures be removed, leaving only the hetman on his steed. A legend propagated in Soviet times was that the mace in the sculpture pointing towards Moscow symbolized Khmelnytsky's geopolitical choice.

sources

- Faith Hillis, Children of Rus': Right-Bank Ukraine and the Invention of a Russian Nation (Ithaca and London, 2013), 81–85;

- "Yuzefovich, Mikhail," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1993).

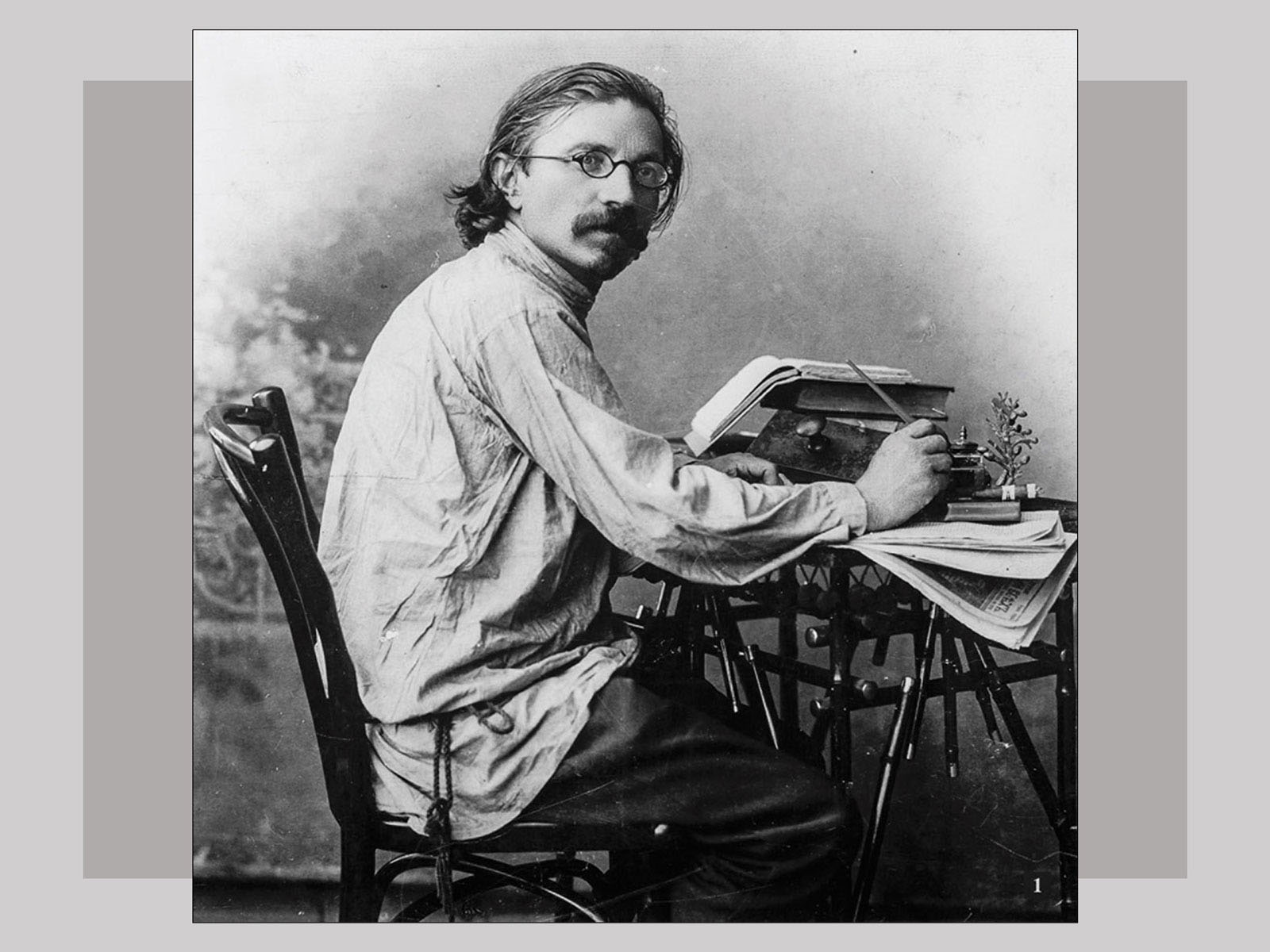

1894–1911

Sholem Aleichem published a series of short stories that would form his best-known work, Tevye der milkhiker(Tevye the Milkman). The Tevye stories eventually appeared in book form in 1911, with another episode added in 1914. The stories are held together by the personality of Tevye, its narrator-protagonist, a traditional but flamboyant and humorously loquacious village Jew who delivers dairy products to the wealthy inhabitants of "Boyberik" (Boyarka), a summer colony adjacent to the great "Yehupets" (Kyiv). The stories are essentially about generational change and the fate of Jews in the Russian Empire, exemplified by the life choices made by Tevye's daughters.

Read more...

In the 1960s, Sholem Aleichem's Tevye stories were transformed into Fiddler on the Roof, the Broadway musical classic. A theatrical adaptation in Ukrainian has been the longest-running play in Kyiv. In addition to the Tevye stories, Sholem Aleichem published extensively in many genres, in Russian, Hebrew, and Yiddish, including six novel-length works of fiction by 1890. As observed by Dan Miron, Yiddish literature before then “lacked cultural status and artistic respectability….Most of its writers hid behind pseudonyms, saving their real names for their productions in other languages." Sholem Aleichem's wanted to elevate Yiddish literature to the status of a Jewish national literature, together with Hebrew.

After 1890 — when Sholem Aleichem moved from Kyiv to Odesa following irresponsible business transactions that led him to bankruptcy — he depended on income from rapidly produced feuilletonistic sequences. Popular literary output in this format — such as the Tevye stories and the tales of the quintessential shtetl, Kasrilevke — made Sholem Aleichem a household name in the Yiddish world. In 1908, he toured throughout the Jewish Pale of Settlement, performing monologues spoken by specific characters and often addressed to a fictionalized interlocutor (such as "Sholem Aleichem" in the Tevye stories or the character "Menachem Mendl" who accompanied the author throughout most of his creative life, especially in the later political feuilletons in the form of letters). By artfully blending comedy and tragedy, Sholem Aleichem's monologues often conveyed messages of universal import.

sources and related

- Dan Miron, "Sholem Aleichem," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (online update, 2013);

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. II, 244.

Related

Chapter 6.4 1860s–1900s

1898

Lazar Brodsky paid 95,000 rubles for building the Choral Synagogue at 13 Mala Vasylkivska Street in Kyiv. The following year his brother Lev built the Merchant Synagogue on the same street.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. II, 195.

1898–1911

While continuing his work on the multi-volume Istoriia Ukraïny-Rusy (History of Ukraine-Rus'), Mykhailo Hrushevsky also produced popular single-volume histories of Ukraine. These include Ocherk istorii ukrainskogo naroda (Survey of the History of the Ukrainian People), a general overview of Ukrainian history based on the course he had taught at the Russian Higher School of Social Studies in Paris in 1903, and the popular Iliustrovana istoriia Ukraïny (Illustrated History of Ukraine), published in 1911.

Read more...

Hrushevsky was also an essayist, belletrist, author of tales, dramas, and short stories, and contributor to the history of Ukrainian literature and other facets of Ukrainian culture. In 1904, Hrushevsky published perhaps his most influential essay — "Zvychaina skhema "ruskoï" istoriï i sprava ratsional'noho ukladu istoriï skhidn'oho slov'ianstva" (The Traditional Scheme of 'Russian' History and the Problem of a Rational Ordering of the History of the Eastern Slavs). While most Russian historians did not accept the essay's central argument — that the Ukrainian nation was distinct from the Russian nation in its origin and its political, economic, and cultural development — they nonetheless accepted Hrushevsky's scheme and periodization of Ukrainian history.

Hrushevsky's multi-volume Istoriia Ukraïny-Rusy (published between 1898 and 1937) has been regarded as the most comprehensive account of the ancient, medieval, and early modern history of the Ukrainian people. In its very title, this work challenged the Russians' monopoly on the name Rus' and asserted the uniqueness of the history and culture of the Ukrainian nation.

Note: The Istoriia won international acclaim at the time of its publication, but in Soviet Ukraine, after the 1930s, no scholarly references to it were permitted, and later Soviet publications dismissed Hrushevsky as a "nationalist historian." Attempts in the 1960s to "rehabilitate" him and his works failed; it was only in the late 1980s that the Ukrainian public began to regain access to his magnum opus.

sources and related

- Oleksander Ohloblyn and Lubomyr Wynar, "Mykhailo Hrushevsky," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine, (1989);

- Frank E. Sysyn, "Mykhailo Hrushevsky and the History of Ukraine-Rus'," "Who was Mykhailo Hrushevsky?" and ciuspress.com.

Related

Chapter 6.1 1906–1912 (Hrushevsky)

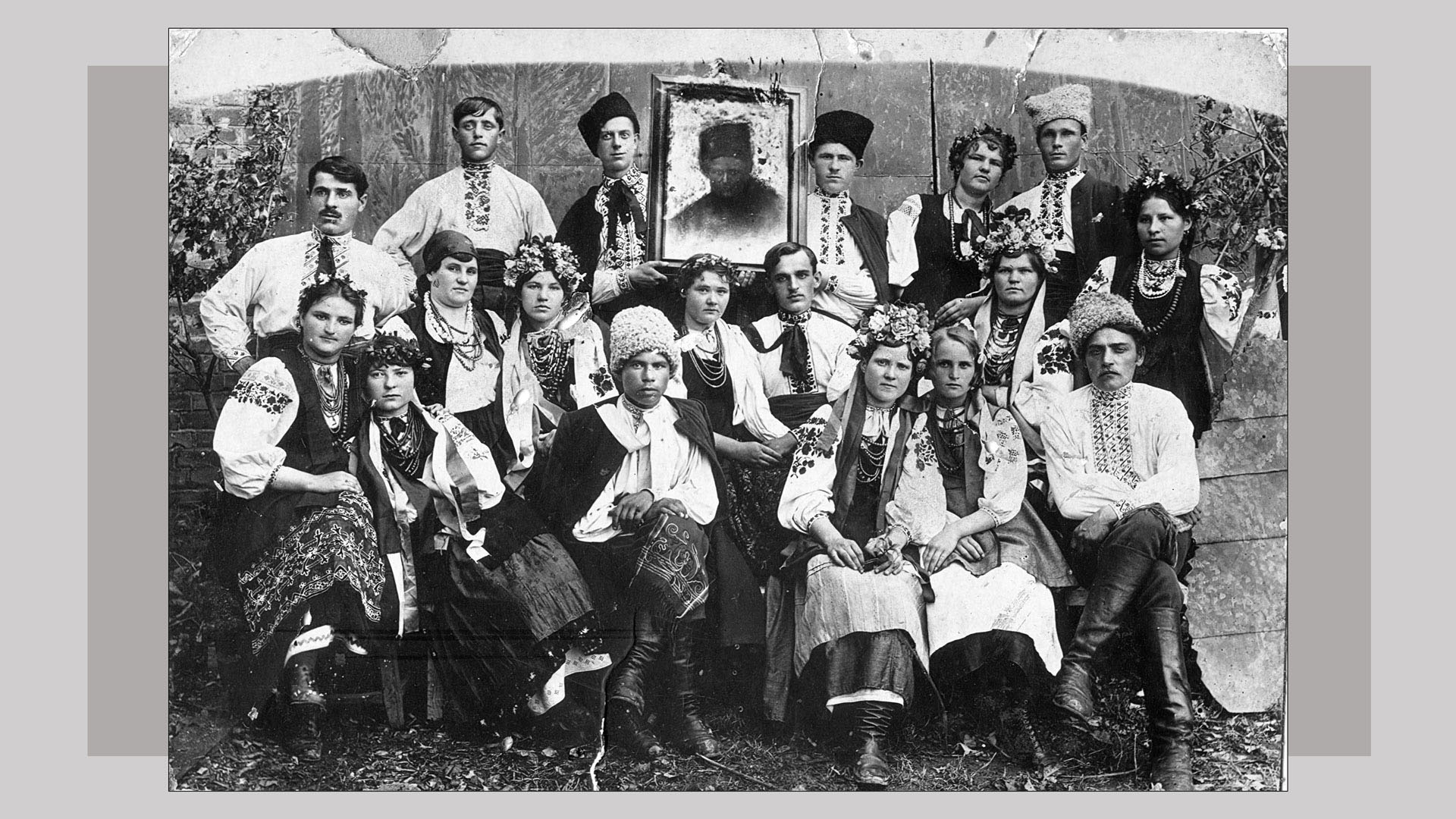

1890s–1900s

Ukrainian ethnography

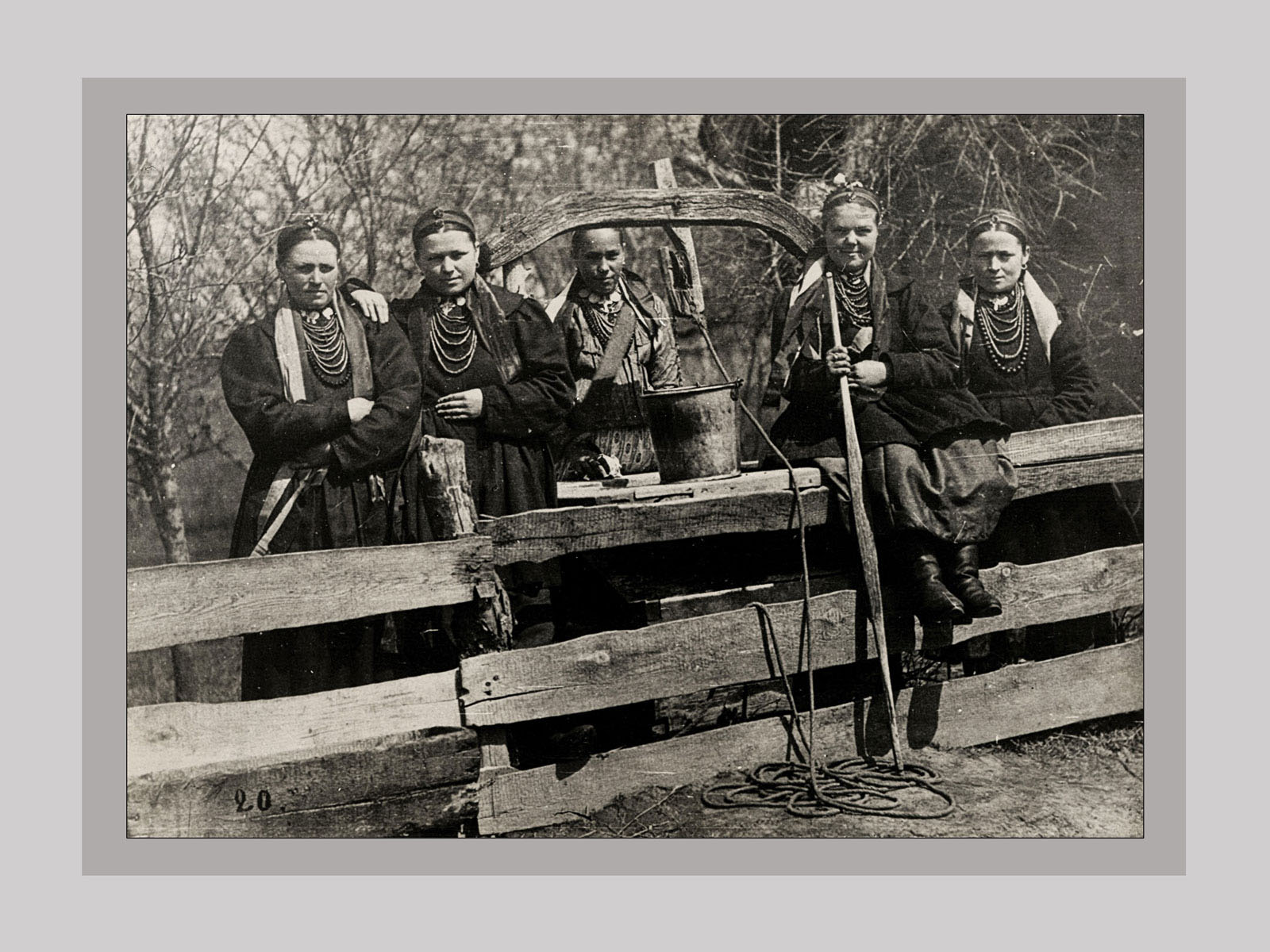

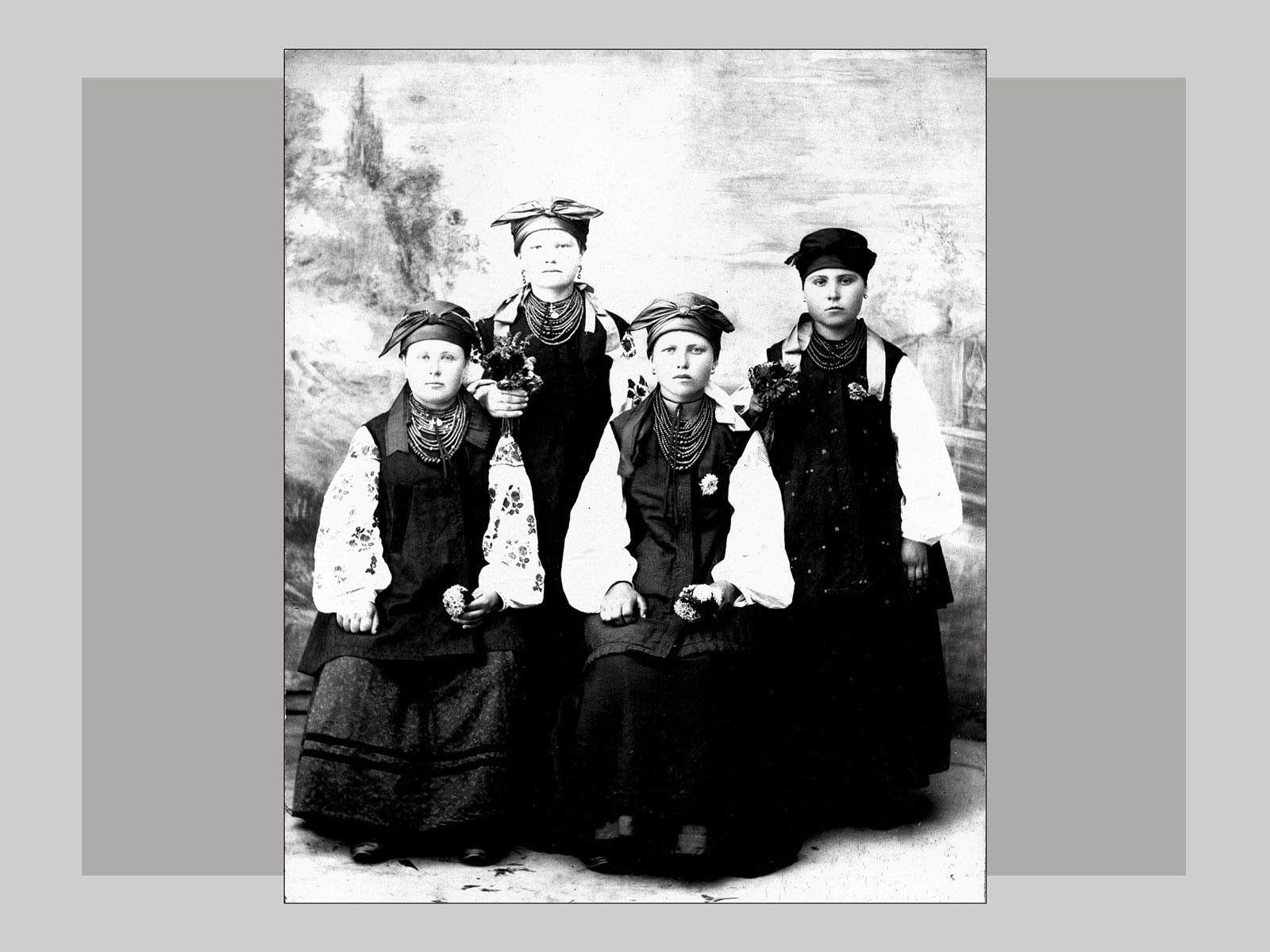

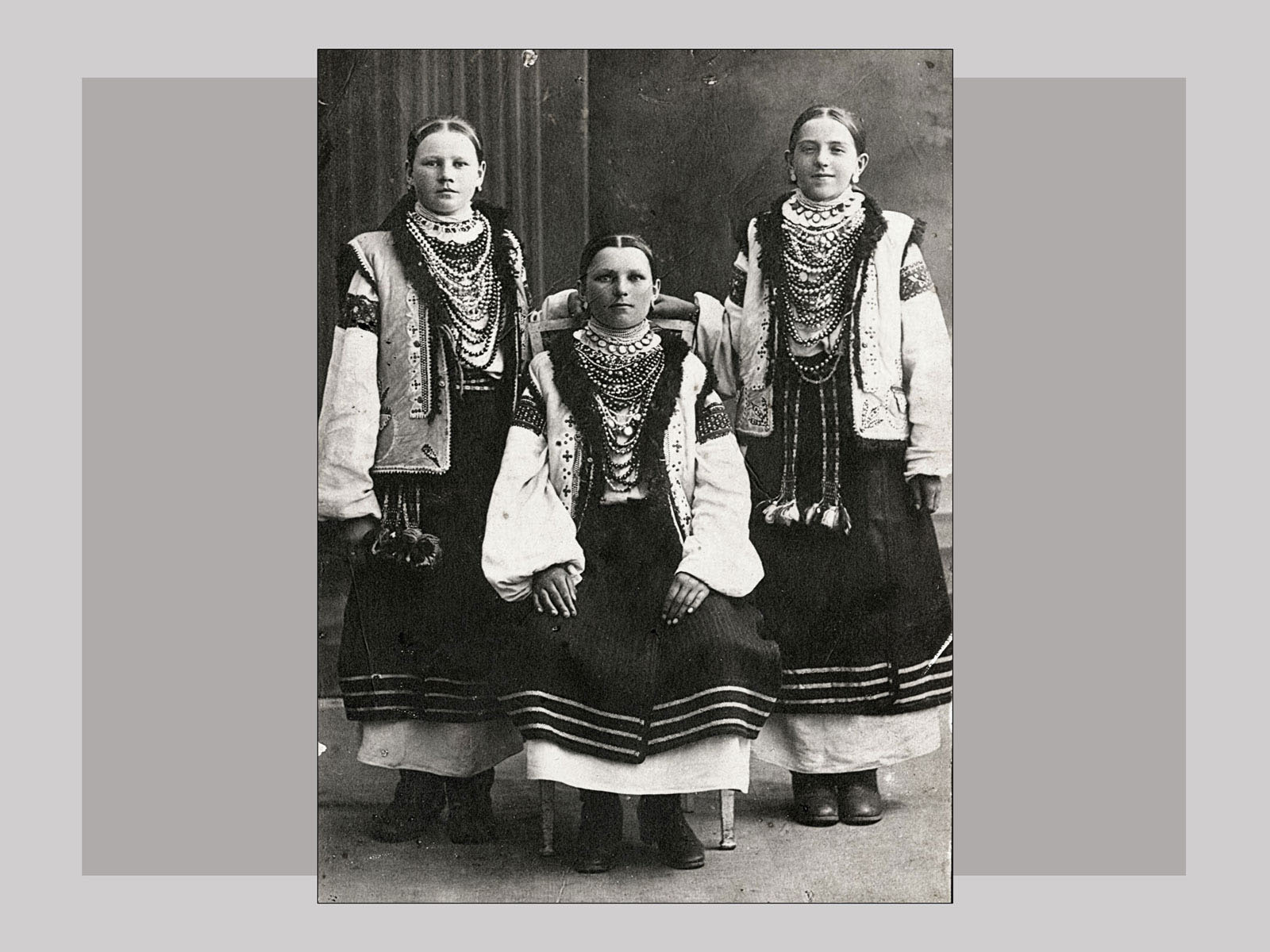

During this period, ethnographic photography proliferated in Ukraine, building upon the increased interest in ethnography more broadly among the Ukrainian intelligentsia. Many of the personalities who influenced the Ukrainian national awakening — including Mykhailo Maksymovych, Panteleimon Kulish, Mykola Kostomarov, Mykhailo Drahomanov, and Ivan Franko — attached great importance to ethnography as a means of strengthening the "national spirit" of the Ukrainian people. Their legacy is preserved in the rich ethnographic collections now held in Ukrainian museums, including songs and stories of the common folk, a wide variety of artifacts, and an abundance of vivid photographs depicting costumes and daily life in the different regions of Ukraine.

sources and related

Related

Chapter 6.4 1827–1849 (Mykhailo Maksymovych )

Chapter 6.6 1858 (Panteleimon Kulish, re: open letter)

Chapter 6.5 1862 (Mykola Kostomarov)

Chapter 6.5 1876–1883

Chapter 6.6 1858 (Kostomarov re: open letter)

1890s–1900s

The sages of Odesa

Odesa's stature as a Jewish intellectual hub was strengthened at the turn of the century. As the centre with the second-largest Jewish population in the Russian Empire (after Warsaw), its Jewish communal institutional life was rich and varied. In addition to its modernist synagogues, the city's modern Jewish schools and literary and philanthropic associations attracted maskilim from smaller towns.

Read more...

The city's local Talmud Torah (headed for many years by the celebrated Hebrew and Yiddish writer Mendele Moykher-Sforim) was widely lauded. The local Jewish clerks' association boasted one of the finest lending libraries in the Pale of Settlement; its holdings in Hebrew and Yiddish were catalogued by the intellectual founder of cultural Zionism Ahad Ha-am and the historian and ideologue of Jewish national autonomismSimon Dubnow. Historians have dubbed these intellectual and cultural leaders "the sages of Odesa."

Despite acculturation and Russification, Jewish cultural identification remained strong in Odesa. In 1911–1912, a mere 34.5 percent of the city's Jewish students said Russian rather than Yiddish was the spoken language in their parents' homes; only 16.1 percent said they had no interest in Jewish matters, and 40.6 percent claimed a good knowledge of Hebrew. Though Odesa was a city where acculturated, Russified local Jews held sway, it was also where intellectuals with cultural nationalist agendas, such as Hayim Nahman Bialik and Moshe Leib Lilienblum, made their mark.

sources

1903

Hayim Nahman Bialik, the poet laureate of the Zionist movement, published his poem Be'ir ha-haregah (In the City of Slaughter) upon visiting the site of the Kishinev pogrom in Bessarabia (today Moldova). The anger the poem expressed was so powerful that it could only be published in tsarist Russia under the title Masa Nemirov (A Tale of Nemyriv), as if it referred to a massacre that took place in Nemyriv during the Khmelnytsky Uprising in 1648–1649. The poem helped establish the violence in Kishinev as the archetypal pogrom. It also underlined the trope of Jewish passivity in the face of pogrom violence and inspired the creation of Jewish self-defence units.

sources and related

1903–1906

Lesia Ukrainka published a series of poetic dramas which describe the dispossession and subjugation of Jews exiled to Babylon and lament the fate of ancient Jerusalem. Among them are Vavylons'kyi polon (The Babylonian Captivity, 1903), Na ruïnakh (Upon the Ruins, 1904), and V domu roboty — v kraïni nevoli (In the House of Labor, In the Land of Slavery, 1906). Following advice from her maternal uncle, the influential scholar and publicist Mykhailo Drahomanov, she drew inspiration for her poetic works not only from Ukrainian history and folklore but also the Hebrew Bible. In a barely veiled manner, she used biblical themes to protest the injustice of the suppression of Ukrainians' cultural heritage within the Russian Empire, awaken national consciousness, and stimulate a struggle for freedom.

sources

- Myroslav Shkandrij, Jews in Ukrainian Literature. Representation and Identity (New Haven, 2009), 56;

- Petro Odarchenko, "Ukrainka, Lesia," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1993).

1905–1914

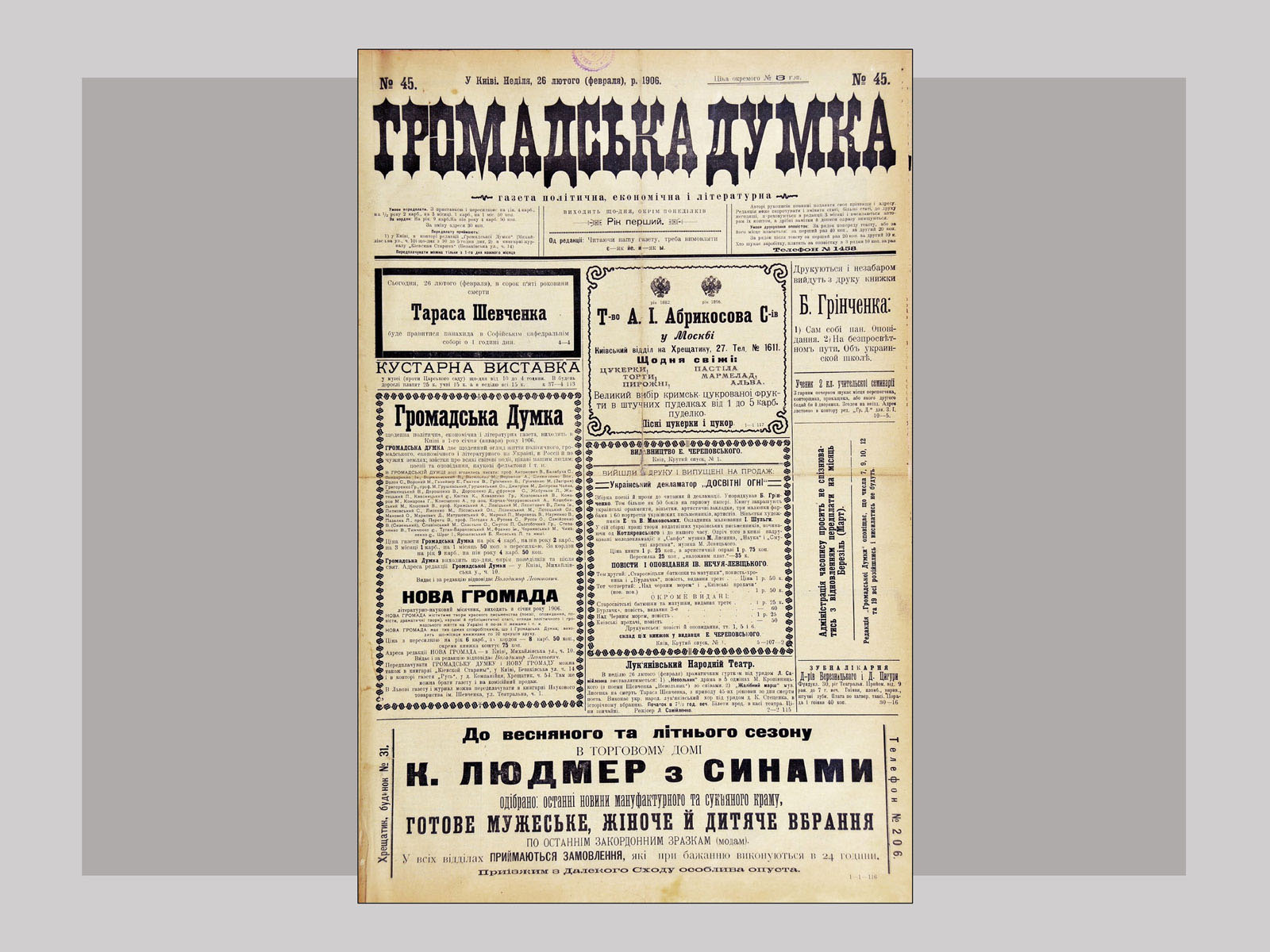

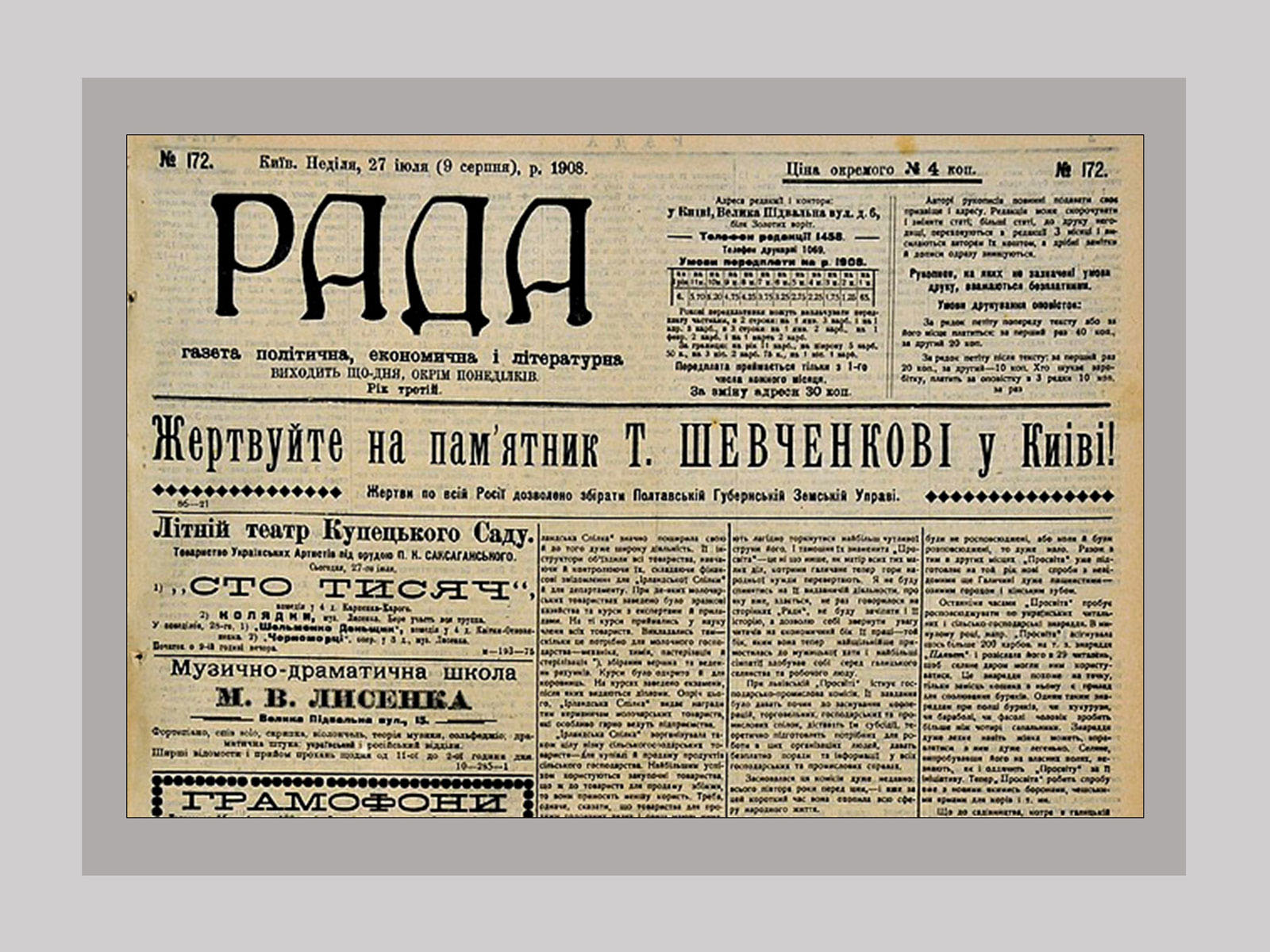

Promoters of the Ukrainian language and culture were encouraged by developments both before and immediately after the 1905 revolution. The Academy of Sciences in Saint Petersburg had declared in March 1905 that the Ukrainian language was not a dialect of Russian but an independent Slavic language and recommended that the restrictions placed on it by the Valuev Circular and Ems Ukase be lifted. In response to revolutionary unrest, the October Manifesto's promise of freedom of the press led to a proliferation of Ukrainian newspapers and journals in Kharkiv, Kyiv, Lubny, Odesa, Poltava, and elsewhere. Eighteen Ukrainian periodicals appeared in 1906; the most important was the daily Hromadska dumka, succeeded by the daily Rada (Kyiv), which initially was an organ of the Ukrainian Democratic Radical party. By 1907, there were nine Ukrainian-language newspapers, with a total print run of 20,000 copies.

Read more...

Inspired (and helped) by the achievements of Ukrainians in Austria-Hungary, Ukrainians in the Russian Empire in 1905–1906 also experienced a proliferation of Ukrainian voluntary associations (including branches of the adult educational and cultural society Prosvita in Kyiv, Odesa, and about a dozen other cities and numerous branches in villages) and a variety of musical, dramatic, and educational clubs.

Many of these achievements, however, were curtailed during the reactionary period that began in 1907. Nonetheless, Ukrainian-language publishing continued to flourish, the most popular genres being the humorously illustrated brochure (850,000 copies between 1908 and 1913) and poetry (600,000 copies).

sources

- John-Paul Himka, "Revolution of 1905," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1993);

- Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe (New York, 2015), 194.

1908

Hrytsko Kernerenko, one of the first Jewish authors to write in Ukrainian, published the poem "Ne ridnyi syn" ("Stepson"), which expresses feelings of loneliness, rejection, and disillusionment in his attempts to acculturate into Ukrainian society. In this poem, he portrays himself as an orphan, adopted by a stepmother, Ukraine. His life has been one of suffering because of the scornful attitude of the other children in the family toward him. He feels that he has to leave his stepmother, as she has been either unwilling or unable to shield this child of a different faith from mistreatment and insults by her own offspring. Yet, he proclaims his eternal love for her as a mother. The underlying message seems to be that even though his Ukrainian-Jewish identity remains a utopian aspiration, he will continue to cherish and reach for it, at least in his humanistic poetical constructs.

Read more...

Kernerenko's other writings, published in prestigious journals and anthologies, include poems and essays about Taras Shevchenko (which the tsarist censors banned) and Ukrainian translations of works by Heinrich Heine, Shimen Frug (who wrote in Russian and Yiddish), and Sholem Aleichem. Kernerenko created explicitly Ukrainian Jewish imagery in his poetry and prose narratives and interacted with leading Ukrainian literary figures. Among the latter, Ivan Franko and Khrystyna Alchevska welcomed him specifically as a Ukrainian-Jewish poet — in effect affirming the feasibility of Ukrainian-Jewish rapprochement in the literary domain.

sources

- Myroslav Shkandrij, Jews in Ukrainian Literature: Representation and Identity (New Haven & London, 2009), 81–83;

- Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, "Ukrainian Literature," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010);

- Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, The Anti-Imperial Choice: The Making of the Ukrainian Jew (New Haven & London, 2009), 50–52.

1912–1914

Jewish ethnography

An-sky led a series of ethnographic expeditions to record the folklore, folk art, and music of Jews in the Pale of Settlement, mainly in Podolia and Volhynia. Participants in the expeditions included a photographer (An-sky's nephew, Solomon Yudovin) and musicologists (Yu. D. Engel and Zusman Kiselgof). The pioneering expeditions collected written, oral and visual materials, as well as religious/ceremonial and household objects evoking images of Jewish life in Ukrainian territories before the First World War.

An-sky's group investigated about 70 towns in the Pale of Settlement, recording over 2,000 folktales, legends, and traditions; over 1,500 folk songs; around 1,000 instrumental and synagogue melodies and drinking songs, as well as customs, ceremonies, superstitions, incantations, proverbs, and parables.

sources

- Benyamin Lukin, "An-ski Ethnographic Expedition and Museum," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2017).