1569–1648

The Union of Lublin agreement between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of Poland created the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (Rzeczpospolita), transforming the relationship between Poland and Lithuania from that of a personal dynastic compact to that of a federated state. Poland established its jurisdiction over Ukraine in the new political arrangement, while Lithuania maintained its rule over Belarus. By the early seventeenth century, the combined territories of the Commonwealth also became home to the largest and most vibrant Jewish community in the world.

Read more...

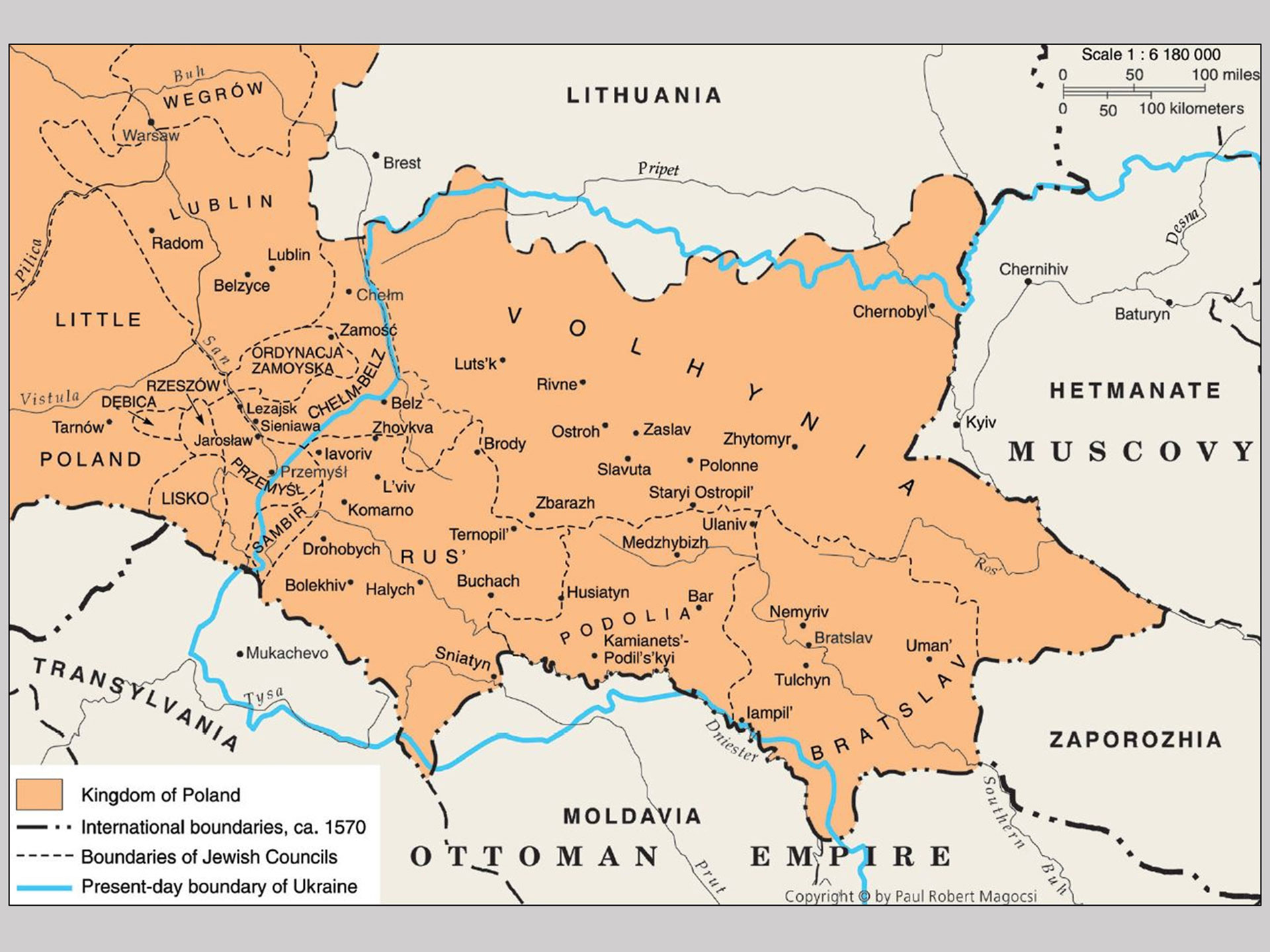

The motivation for the Union was to strengthen both Poland and Lithuania against continuing aggressive advances by Muscovy and to facilitate eastward expansion. As a single, federated state, ruled by a jointly elected monarch, it was to have a common parliament (diet), foreign policy, monetary system, and property law, but separate administrations, law courts, treasuries, and armies. Poland, the dominant partner, already controlled the predominantly Ukrainian/Ruthenian palatinates of Galicia (known as palatinate Rus'), Belz, and Podolia; it now also acquired Volhynia and the palatinates of Bratslav, Kyiv, and Chernihiv.

Most of the Orthodox Ruthenian (Ukrainian) nobility welcomed the Union. They were granted equal rights with their Polish counterparts and looked forward to benefitting from the political and economic advantages that came with being part of the Polish sphere. They were also attracted to the then flourishing Western-oriented Polish culture and soon took on a Polish political identity. For the elite of Ukrainian society, the Union had ushered in a cultural revival — in theological and secular education, literature and the fine arts, and the introduction of printing.

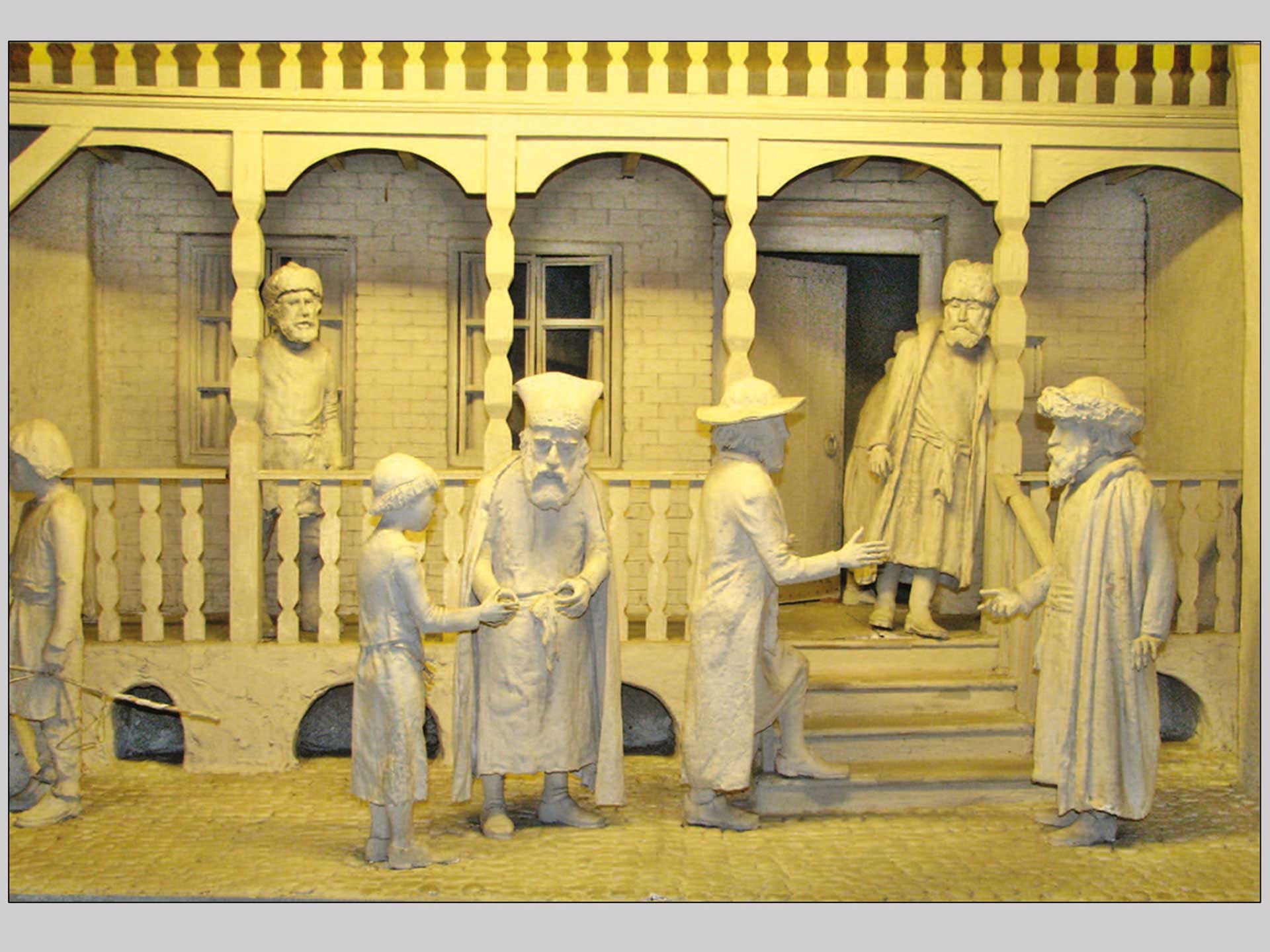

The Union also provided additional resources for the colonization of the previously unsettled areas, where the nobility — Ruthenian and Polish — acquired vast landholdings, for which they needed managers and leaseholders. To fill these roles, they turned to Jews (among others), encouraging a wave of Jewish migration eastward and the establishment of new Jewish communities on Ukrainian lands. However, for the Ukrainian peasantry, the Union created economic burdens and increasingly entrenched serfdom, leading to growing socio-economic, religious, and national tensions, which peaked in a full-scale uprising that engulfed the Commonwealth in 1648.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 140–143, 151, 157;

- "Poland," "Lithuania," "Union of Lublin" Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1993 articles);

- Aliaksei Adamovitch and Ilya Andreyeu, "An unusual, hand-drawn map of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth from the first half of the 17th century."

1550s–1630s

Cossacks

Adventurers, former dwellers of borderland towns, and fugitives from serfdom who settled in the Ukrainian steppe gave rise to a social class known as Cossacks (from the Turkic term "qazaq," meaning freebooting warrior or raider). Over time they were also joined by Tatars and individuals from various nomadic groups from the steppe. Of necessity, the Cossacks became skilled in the art of self-defence and gained a reputation for defending the region against Nogay and other raiders — and also for attacking merchant caravans and Crimean commercial centers.

Read more...

By the end of the sixteenth century, several categories of Cossacks emerged. Those engaged in defending the Duchy of Lithuania's southern frontier settlements became known as "town Cossacks." Powerful Rus' magnates and Poland's kings also employed Cossacks to help defend the Commonwealth's borders. In 1572, the Polish king introduced the "registered Cossacks" system, in effect until 1648, whereby select Cossacks were granted designated rights, such as the right to own land and exemption from taxes, in exchange for their service. Registered Cossacks thus had a vested interest in maintaining stability in the Commonwealth.

Most resonant historically are the non-registered Cossacks living in Zaporizhia (the area beyond the cataracts in the Dnieper River). These Cossacks lived around an administrative and military center known as the sich, which was relatively independent of the Polish political system. The ranks of the Zaporozhian Cossacks continued to be increased by peasant fugitives from serfdom and dissatisfied townspeople. Most were Orthodox Slavs and ancestors of modern-day Ukrainians. They acquired military strength and prestige as they battled the Turks and rescued captives destined for the Ottoman slave markets — themes that became part of Ukrainian folklore.

Cossack armies engaged in a series of uprisings (1590–1638) that established their reputation as a formidable military force and Cossacks as a distinct social order that challenged the authority of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The revolts were motivated primarily by the Polish administration's non-recognition of Cossacks as a separate social estate with distinct privileges, such as accorded to the szlachta. After 1620, the Cossack uprisings acquired religious overtones in response to tensions arising from the regime's promotion ofthe Roman Catholic Church and the Uniate Church and its repression of the Orthodox Church. Following the failure of the revolts, the Polish authorities treated the Zaporozhian Cossacks as outlaws. Deep-seated mutual distrust intensified as the rebel Cossacks came to be viewed and viewed themselves as defenders of the peasantry and the Orthodox faith.

At the same time, the Cossack victories over the Tatars incentivized Polish and Lithuanian magnates to promote rural and urban settlement on the vast territories of the Ukrainian steppe east of the Dnieper River, opening the possibility for Jews to settle there.

sources and related

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Ukraine: An Illustrated History (Toronto, Second Edition, 2007), 85–88;

- Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe (New York, 2015), 75–77, 359–360;

- Albert Seaton, The Horsemen of the Steppes. The Story of the Cossacks (New York: Hippocrene Books, 1985), 17–20, 29–31.

Related

Chapter 3.1 1449–1783 (Read More)

1580–1764

Development of Jewish self-governance

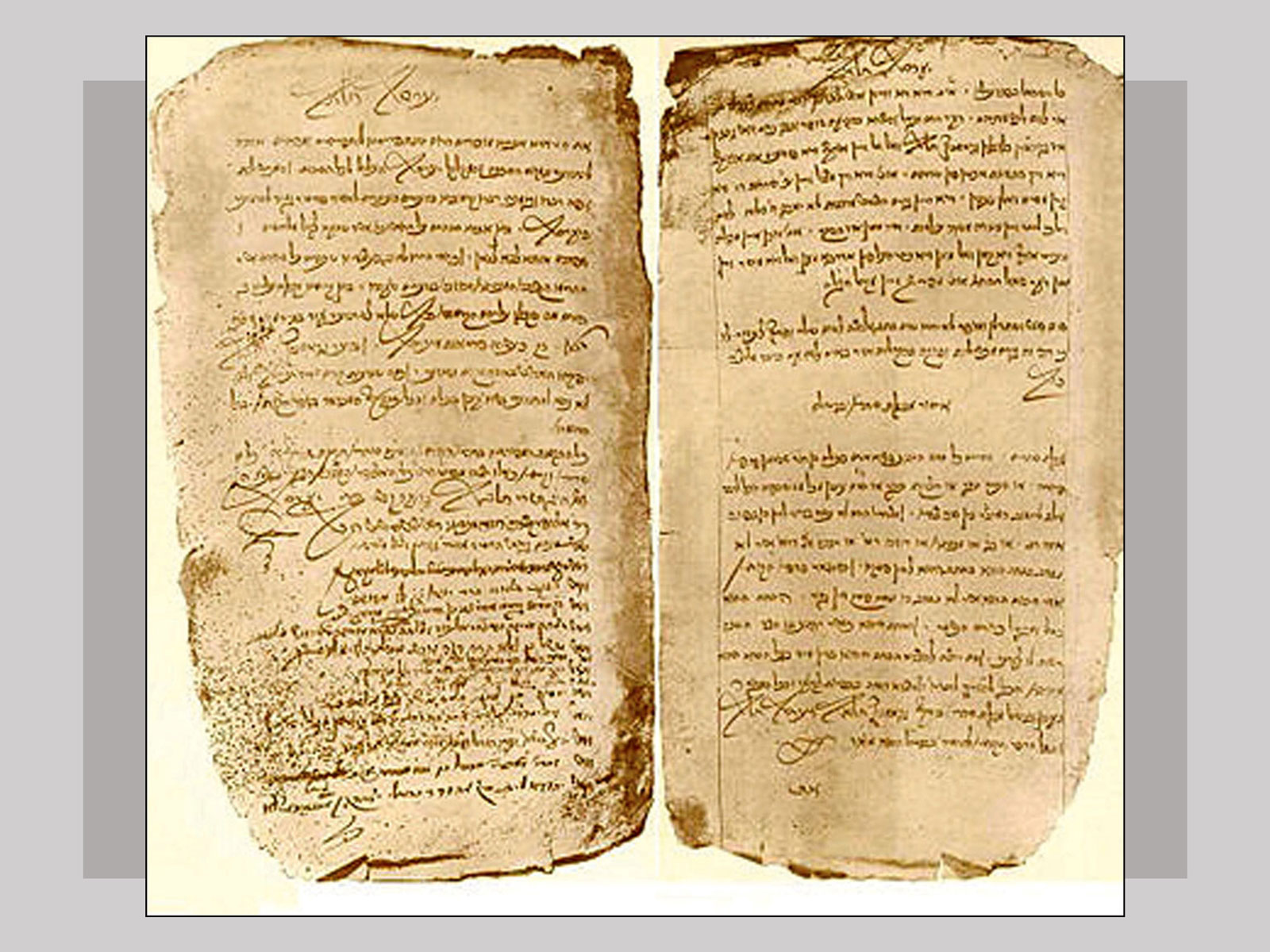

The Council of Four Lands (Heb. va'ad arba' aratsot) emerged (ca. 1580) as the central institution of Jewish self-governing limited autonomy in Poland-Lithuania, largely in response to the authorities' decision to reimpose a Jewish collective poll tax.

Read more...

The initial "four lands" were Greater Poland, Little Poland, Ruthenia (Galicia), and Volhynia. (The Jewish communities in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania formed a separate council in 1623.) The Council's principal function was to apportion the collective tax burden among the Jewish communities and to settle disputes in this regard. It took on additional essential functions, however, such as serving as a unified voice for ongoing representation of Jewish interests to the Polish crown and central government institutions, as well as coordinating lobbying activities at times of crisis, when individuals or communities came under attack, or in cases of blood libel accusations, or impending unfavourable legislation.

The Council met twice yearly at Poland-Lithuania's most important trade fairs, where provincial parliaments of the local nobility also convened. Much of the Council's activity was concerned with helping to preserve communal and inter-communal harmony. Though it had limited jurisdiction over the individual communities that made it up, it could act as a court of appeal from decisions of Jewish local and regional courts. Though it was initially a lay body with no rabbinic members, it enjoyed considerable prestige, functioning alongside a national tribunal of eminent rabbis, with whom it would meet, when important matters arose, to draft legislative decisions for approval by individual communities.

In 1764, the Polish sejm (parliament) decided to abolish the Council of Four Lands, motivated by complaints from the nobility about how the poll tax had been administered, as well as an Enlightenment-inspired aversion to particularist jurisdictions.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford and Portland, OR, 2010), vol. I, 41, 48–49, 59–63;

- Adam Teller and Igor Kakolewski, "Paradisus Iudaeorum, 1569–1648," Polin: 1000 Year History of Polish Jews (Warsaw, 2014), 110;

- Moshe Rosman, "Poland: Poland before 1795," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1648–1654

The Khmelnytsky uprising and the Cossack state

Fueled by rising social, ethnic, military, and religious tensions, a major Cossack uprising in 1648, led by Bohdan Khmelnytsky against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, led to the expulsion of Polish landowners, massacres of Jews and Poles, and the creation of a Cossack state known as the Hetmanate. The success of the uprising may be attributed in part to an alliance Khmelnytsky forged with the Crimean Tatars and support from peasants rebelling against the burdens of serfdom and manorial duties. In Ukrainian historical memory, Khmelnytsky is regarded as a hero who led a war of national liberation. He became a central figure in the rich Ukrainian literary and oral bardic tradition that celebrates the Cossack age and associates it with freedom from oppression. From the Polish and Jewish perspectives, Khmelnytsky is a notorious figure, his troops having perpetrated unprecedented massacres of thousands of Roman Catholic Poles and Jews.

Read more...

Following Khmelnytsky's orders, the radical Cossack leaders Maksym Kryvonis and Danylo Nechai carried out the slaughter of the Jewish population of Medzhybizh and further serious atrocities throughout the Kyiv palatinate. The anti-Jewish violence, graphically described in Jewish chronicles of the period, had a profound and enduring impact on Jewish historical memory.

Khmelnytsky became controversial also because the accords he signed with the Muscovite tsar in 1654 led to increasing Russian control of Ukraine.

sources

- Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe (New York, 2015), 360;

- Frank E. Sysyn, "The Jewish Factor in the Khmelnytsky Uprising," in Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective, Peter Potichnyj & Howard Aster, eds. (Edmonton, 1988), 52;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 213–216;

- "Khmelnytsky, Bohdan," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1989);

- Shaul Stampfer, "Gzeyres Takh Vetat," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1649

The Cossack state (the Hetmanate) was established following an agreement with the Poles in Zboriv. The agreement defined Cossack territory as consisting of the palatinates of Kyiv, Chernihiv, and Bratslav, collectively designated as Ukraine. The Treaty of Zboriv specified the Cossacks' demand that Jews who did not convert be banned from the Cossack state. Some did convert and remained as urban-dwelling merchants and, in some instances, became Cossacks.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 219, 264, 267, 295–296.

1654–1686

In the Pereiaslav treaty (1654), the Cossack leader Bohdan Khmelnytsky recognized the suzerainty of the tsars of Muscovy, leading to a prolonged confrontation between Muscovy and Poland-Lithuania over control of Ukraine. The agreement, negotiated by the Orthodox Church, resulted in Muscovy's annexation of the Ukrainian-inhabited former Polish palatinates of Chernihiv, Kyiv and Bratslav, as well as the Zaporozhian steppe farther south on both sides of the Dnieper River. While Khmelnytsky and his Cossack successors viewed Pereiaslav as a voluntary political agreement open to further negotiations, Muscovy considered it an act of subordination and an opening to territorial annexation. For Ukraine, the treaty was followed by a period marked by anarchy, foreign invasion, civil war, and peasant revolts — the "Period of Ruin" (1657–1686).

sources

- Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe (New York, 2015), 360;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Ukraine: An Illustrated History (Toronto, Second Edition, 2007), 101–103.

1667–1686

The Truce of Andrusovo divided Ukraine more or less along the Dnieper River between Poland and Muscovy, provoking a Cossack uprising against both powers, led by Hetman Petro Doroshenko. The division split the Cossack Hetmanate into two parts, which at times were in conflict with each other. During this period, the Hetmanate also lost territory to the Ottomans, who took over a large swath of territory in Ukraine (including the Podolia, Bratslav, and southern Kyiv palatinates) after defeating the Poles in 1672. The so-called "Eternal Peace Treaty" of 1686 left Ukraine with little hope for independence or even broad autonomy, with its territory divided among Poland, Muscovy, and the Ottoman Empire. In what remained of the Cossack Hetmanate, two groups, the Rus' gentry and the Cossacks, had their status recognized. Others, such as Roman Catholic clergy and Jews, were driven out to Ukrainian territory under Polish rule. Some historians attribute the expulsion of the Jews from the Hetmanate to Muscovy's exclusionary policies towards Jews, in accordance with the anti-Jewish precepts of the Russian Orthodox Church.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 241, 247, 264;

- Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe (New York, 2015), 360.

1686–1711

The Cossack Hetmanate experienced a period of stability under Cossack leader Ivan Mazepa after Poland renounced claims to Left-Bank Ukraine and Kyiv and recognized Muscovite suzerainty over the Zaporizhian Cossacks. Mazepa's primary goal as hetman was to unite all Ukrainian territories in a unitary state that would be modelled on existing European states but would retain the features of the traditional Cossack order. When Muscovy appeared to be undermining Cossack rights and autonomy, Mazepa led a revolt against Tsar Peter I and forged an alliance with the advancing army of Charles XII of Sweden. A resounding Muscovite victory over the combined Swedish-Cossack armies at the Battle of Poltava in 1709 led to the abolition of the hetman's office and the slow erosion of the Hetmanate's autonomy. Thereafter, Mazepa was vilified as a traitor in imperial Russian (and Soviet) narratives but remained a symbol of Ukrainian independence.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 253, 258–;

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford and Portland, OR, 2010), vol. I, 173–74;

- Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe (New York, 2015), 361;

- Oleksander Ohloblyn, "Mazepa, Ivan," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (2008);

- Tatiana Tairova-Iakovleva, "Peter I's Administrative Reforms in the Hetmanate during the Northern War," in Serhii Plokhy (ed.), Poltava 1709: The Battle and the Myth (HURI, Harvard 2012).

1768

The Koliivshchyna uprising, the largest of a series of eighteenth-century revolts by bands called Haidamaky, brought unrest to many regions of Ukraine, including the Kyiv, Podolia, Bratslav, and Volhynia regions. The uprising culminated in Uman (in central Ukraine) with the massacre of several thousand Poles and Jews.

Read more...

Zaporozhian Cossack leader Maksym Zalizniak organized the uprising after Polish nobles formed the Confederation of Bar, which the rebels perceived as an alliance intent on destroying all adherents of the Orthodox faith. The rebel bands — consisting of fugitive Orthodox serfs, impoverished Cossacks, and disgruntled townspeople — plundered and burned towns and nobles' estates in the Kyiv palatinate and in Bratslav, Podolia, and Volhynia. In Uman, the captain of the Cossack militia, Ivan Gonta, abandoned the Polish nobles who employed him and joined Zalizniak's forces. The rebellion was soon crushed with the help of Russian troops, accompanied by Polish pacification actions in which thousands of peasants were killed. The Haidamaky revolts contributed to the weakening of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, paving the way for the Partitions of Poland and increasing Russian political and military influence in these lands.

Perhaps the most enduring impact of the 1768 revolt lies in the historical memory of Ukrainians, Poles, and Jews. For Ukrainians, it became a symbol of resistance to social oppression. For Poles, it was either an example of Cossack barbarism against Polish civilization or a lesson pointing to the need for a joint Polish-Ukrainian stand against tsarist oppression. For Jews, the Uman massacre is another historic instance of Jewish martyrdom, "the second Ukrainian catastrophe" (after the Khmelnytsky-era massacres). Uman would later become a major pilgrimage site because the Hasidic leader Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav chose to live and be buried there in order to be close to the Jewish martyrs of 1768.

sources and related

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 313–317;

- Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe (New York, 2015), 361.

Related

Chapter 4.5 1768

1772–1795

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was partitioned between Austria, Prussia, and Russia. Galicia, with its large population of Ukrainians, Poles, and Jews, came under Austrian Habsburg rule. Volhynia and Ukrainian lands further east came under Russian rule.

By the end of the eighteenth century, the vast majority of Ukrainian territories had come under Russian rule. The landowners in Ukraine east of the Dnipro, known as Left-Bank Ukraine, were Russophone Ukrainians or Russians. West of the Dnipro, in Right-Bank Ukraine, the majority of the landowners were Polish. In Galicia, the landlords were still Polish. In Transcarpathia, the elite was Hungarian. In Bukovina, where serfdom obligations were lighter, landlords could be Romanians, Greeks, or ethnic Ukrainians. Throughout these territories, the peasantry was enserfed and, for the most part, ethnically Ukrainian. Ukrainian lands were also home to a significant Jewish minority, primarily engaged in trade, crafts, and innkeeping. Jews made up about 12 percent of the population in the Right Bank and about 5 percent in the Left Bank. The southern Ukrainian lands also attracted Jewish settlers, especially merchants drawn to the trading centers of Odesa and Kherson. In Galicia, around 10 percent of the population was Jewish.

sources

- John-Paul Himka, Ten Turning Points: A Brief History of Ukraine.