870s–1054

Kyivan Rus'

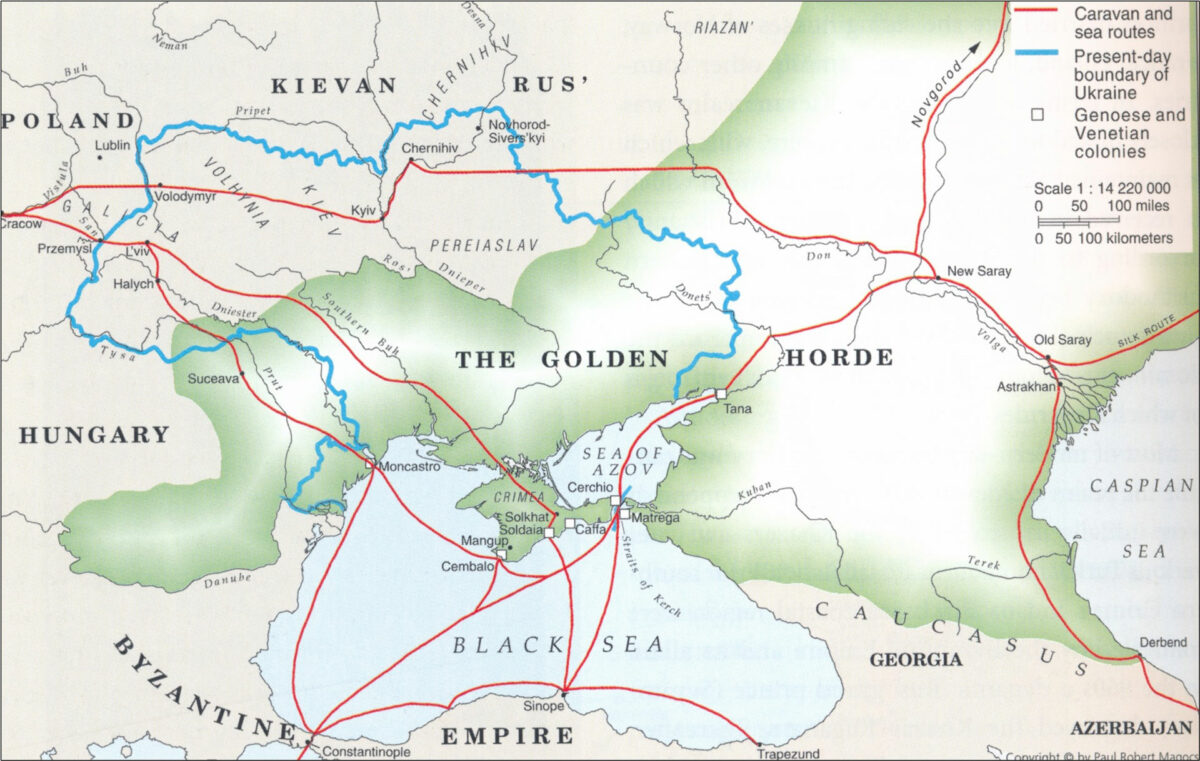

Scandinavian voyagers (called Varangians) discovered water routes through the East European forests and steppe, leading to the major trading hub, Constantinople. Along the way, they set up trading posts, including in Kyiv on the Dnipro River, which evolved into towns that eventually united to become the political entity known as Kyivan Rus'. In medieval times that state was known simply as Rus' and from the eleventh century also as Ruthenia. These names are distinct from the modern name of Russia, which came into use in the fifteenth century. Both Ukrainian and Russian historians treat Kyivan Rus' as an integral part of their respective national histories.

The origins of the Rus' people and their state are shrouded in uncertainty and controversy. Historians believe that Kyivan Rus' was inhabited mainly by East Slavs, who established several tribal unions, each with its own political and economic stronghold. The Varangians gradually mixed with the Slavic nobility and assimilated into the local culture. During this period, the Kyivan state maintained contacts with Western and Central European countries, including by intermarriage of its rulers with European dynasties. A small number of Jews resided in Kyivan Rus' alongside the East Slavic majority.

Read more...

Rus' written sources refer to groups of Jews living in the Podil district in the lower section of Kyiv already in the early tenth century. The leaders of the community included not only Jews from the Khazar Empire and local Jews who adopted Slavic names but also Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazi migrants, likely from Bohemia and Moravia (present-day Czech Republic), who maintained links with Jews in Germanic lands.

In the first formative stage of Kyivan Rus' (878–972), rulers of Scandinavian origin succeeded in bringing the East Slavic and Finnic tribes under their control. After the dynamic Rus' grand prince Sviatoslav destroyed the Khazar Empire in the late 960s, the rule of the Rus' princes extended as far as the steppe. The steppe, however, was an unstable region inhabited by warring nomadic Turkic tribes, who often engaged in battle with the Rus' princes.

The second stage (972–1132) was one of consolidation of Kyivan Rus' into a loose conglomerate of principalities linked by family ties, with administrative responsibility for a vast and expanding territory. Kyivan Rus' was at its peak during the reigns of Volodymyr ("the Great," r. 980–1015), marked by the Rus' adoption of Byzantine Christianity, and Yaroslav I ("the Wise," r. 1019–1054), whose reign was followed by the bitter schism between Roman Catholicism and Eastern orthodoxy. During this period, relations with the nomads of the steppe evolved beyond conflict — to trade, military alliances, and intermarriage.

sources

- Orest Subtelny, Ukraine (Toronto, Toronto University Press, Third Edition, 2000), 25–37, 52;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Toronto University Press, Second Edition, 2010), 55–59;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence (Toronto, Second Edition, 2018), 15–19.

- John-Paul Himka, Ten Turning Points: A Brief History of Ukraine.

1132–1240

Two contradictory trends marked this period: greater integration attributable to the spread of Christianity, and political disintegration due to a decrease in the authority of Kyiv and the emergence of alternative power centers among the principalities.

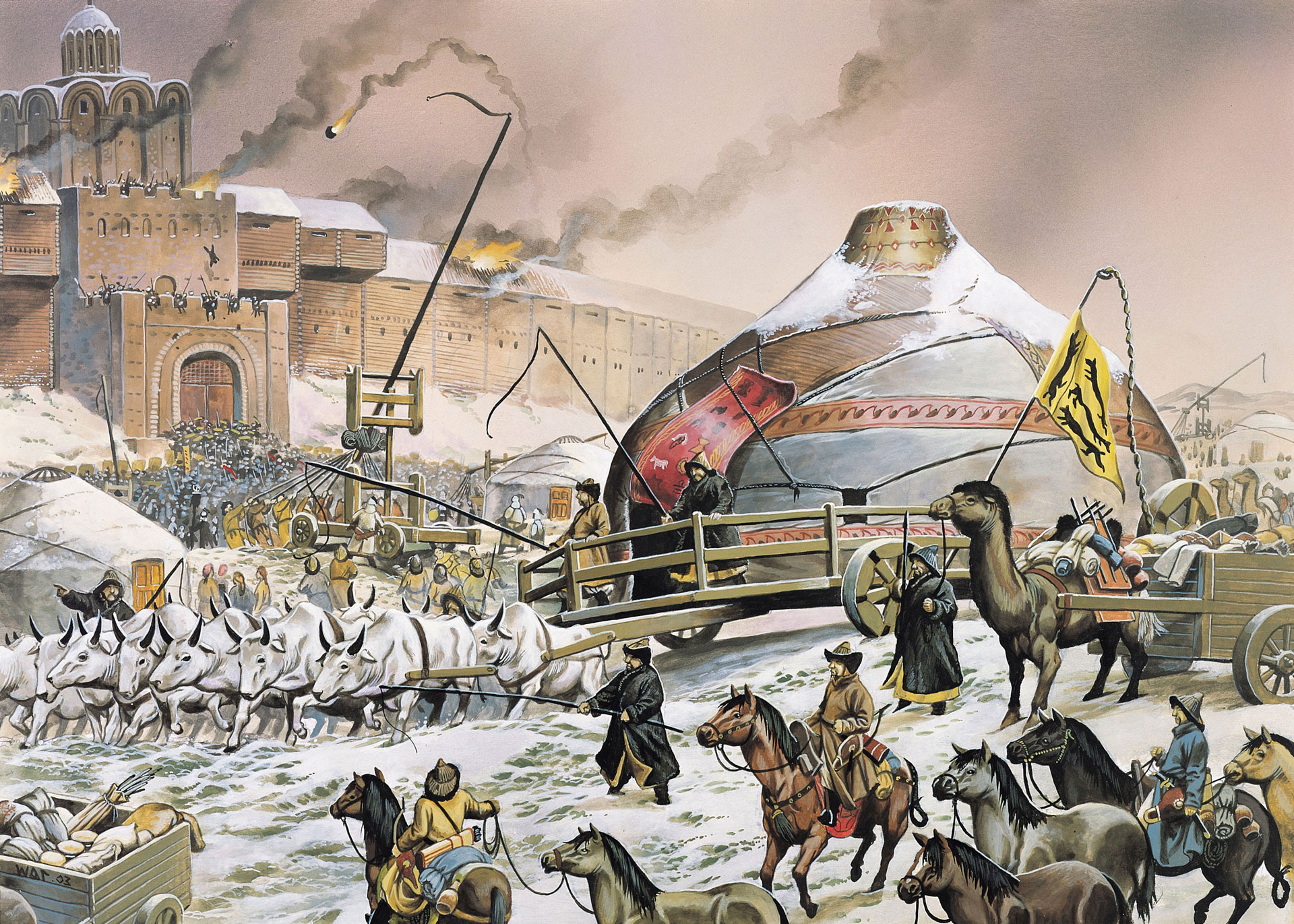

Civil strife between rival Rus' princes culminated in the disintegration of Kyivan Rus' into separate principalities, often attacked by Turkic warriors from the east. The most destructive attacks came from Mongol armies, comprised mainly of Turkic groups known by the generic name Tatars. An attack in 1223 by the armies of Chinggis (Genghis) Khan concluded with their retreat to Mongolia, even though they had routed a joint Rus'-Polovtsian force. Their return in 1236, however, with massive armies under the command of Chinggis Khan's grandson, Khan Batu, led to major Mongol conquests in eastern Europe, including of several Rus' principalities and, in December 1240, Kyiv itself.

The Mongol invasion is perceived historically as the beginning of a dark age of destruction, subjugation, and loss. At the same time, the Mongols sought to establish a stable political environment conducive to their control of the valuable trade routes that passed through the region. To maintain stability, they tolerated a continuing role for the Kyivan Rus' rulers, as long as they acknowledged and paid an annual tribute to the Mongol-Tatar authorities.

sources

- Orest Subtelny, Ukraine (Toronto, Toronto University Press, Third Edition, 2000), 37–41;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Ukraine: An Illustrated History (Toronto, 2007), 45–50;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence (Toronto, Second Edition, 2018), 15–17;

- "Batu Khan," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine.

1187

The oldest reference to the name Ukraїna is found in an early twelfth-century Kyivan Rus' chronicle, The Primary Chronicle, in connection with the death in 1187 of the Rus' Prince Volodymyr of Pereiaslav. According to a fifteenth-century copy (the Hypatian text) of The Primary Chronicle: "The Ukraїna groaned with grief for him." Scholars believe that the name Ukraїna referred to the steppe borderland from Pereiaslav in the east to Galicia in the west, rather than to a specific territory.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 189;

- Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe (New York, 2015), 358.

1238–1340s

Galicia-Volhynia

Together with the principality of Volhynia, Galicia functioned (until 1240) as a hub of both east-west trade linking Kyiv (via Cracow) to Hungary and north-south trade from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea. At the invitation of the politically influential land-owning social stratum (the boyars), the Romanovych dynasty became the rulers of Galicia and Volhynia as a united principality. After sacking Kyiv and other Rus' principalities, the armies of the Mongol ruler Batu Khan penetrated Galicia, Poland, and Hungary. By 1242, the Golden Horde's domain encompassed all of the southern steppe Ukraine and the Crimea.

Read more...

Batu prevailed on Prince Danylo to become his vassal and reap the benefits of the Pax Mongolica — the provision of peaceful stability in exchange for annual tributes of grain and other goods. Though perceived as a humiliation, the policy of submission to the Mongols ensured stability and prosperity in Galicia-Volhynia for several decades, a welcome change from the inter-princely wars and frequent nomadic raids that marked the previous era.

Prince Danylo and his successors ruled over the re-unified, independent Rus' principality and later kingdom of Galicia-Volhynia, which included most Jews then living on Ukrainian territory. During Danylo's reign and that of his son Lev, Galicia-Volhynia, with its capital in Lviv, reached the apex of its political power and economic influence.

During King Lev's reign, rulers in neighbouring Polish lands granted a number of formal privileges to Jews in order to regulate the conditions of their residence in the realm. These privileges and conditions set precedents for the toleration of Jewish communal life under subsequent Polish-ruled regimes on Ukrainian lands.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Ukraine: An Illustrated History (Toronto, 2007), 51–56;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 125–126, 154;

- "Batu Khan," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine;

- Moshe Rosman, "Poland: Poland before 1795," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010);

- Bernard D. Weinryb, The Jews of Poland (Philadelphia, JPSA, 1972), 134–155.

1340–1392

The once-powerful principality of Galicia-Volhynia entered a period of decline as a result of several factors. These include its anti-Mongol stance, challenges from the influential aristocratic landowners (the boyars), and the impact of two military campaigns (1340 and 1349) against the principality, led by Casimir III ("the Great") of Poland. While historical evidence does not support the claim that Casimir the Great brought Jews to Poland, he did grant Jews certain privileges in the lands under his rule, superior to those they enjoyed in other lands. By 1387, Galicia-Volhynia was divided, with Galicia becoming part of the Kingdom of Poland, and Volhynia, along with the Dnieper region, acquired by the Lithuanian princes.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Ukraine: An Illustrated History (Toronto, 2007), 56;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 129;

- Hanna Zaremska, "First Encounters, 960–1500," in Polin: 1000 Year History of Polish Jews (Warsaw, 2014), 70.