1772–1840s

Modern historians agree that Maria Theresa was perhaps the most anti-Jewish monarch of her day. Her antipathy was manifest in policies that created considerable hardship for the Jews in her realm, including the expulsion of the Jews from Prague in 1744 and extremely high taxes on Jewish subjects. As late as 1777, she reaffirmed her opposition to a Jewish community in the imperial capital of Vienna, penning the much-cited antisemitic statement: "I know of no greater plague than this race, which on account of its deceit, usury and avarice is driving my subjects to beggary. Therefore as far as possible, the Jews are to be kept away and avoided."

During the first years of Galicia's annexation to the Habsburg Empire, Galician Jews were subject to discriminatory taxation policies, residence restrictions, and exclusion from a range of occupations. The discriminatory policies were introduced by Empress Maria Theresa and Joseph II in 1776; they were mostly maintained (and even increased) by their successors until October 1848.

Read more...

Most onerous was the special tolerance tax on Jews and the expulsion of those who failed to make regular payments. Other special Jewish taxes were introduced — for registering a marriage, for example. In response to pressure from burghers, restrictions were imposed on where Jews could live, leading to the assignment of ghetto-like special Jewish districts in Lviv, Sambir, and Horodok. Jews were effectively barred from merchant and artisan guilds and from occupations such as pharmacist (until 1831), brewer, distiller, and miller. They could not be appointed to positions in the state, municipal, or judicial system, nor could they be teachers in the state schools.

While Austrian officials provided security from pogroms for Jewish residents, they actively interfered in the life of the Jewish community, including deportation of the poor, and severely restricted their sources of livelihood.

sources

- Marc Saperstein, "In Praise of an Anti-Jewish Empress," Shofar (Purdue University Press, Fall 1987), 20-25;

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. I, 254–257;

- Myron Kapral, "The Jews of Lviv and the City Council in the Early Modern Period," in Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry, Volume 26, Jews and Ukrainians, eds. Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Antony Polonsky (Oxford, 2014), 100.

1850s–1900s

The Roman and Greek Catholic churches in Galicia shared the standing Christian attitudes toward Jews. Until well past the middle of the nineteenth century, Catholic bishops in Galicia issued pastoral letters that reflected medieval Christian prejudices against Jews, notably the perception of Jews as Christ-killers.

By the mid-nineteenth century, modern socioeconomic motifs entered the anti-Jewish discourse. The anti-alcohol campaign, in which priests were active, often included anti-Jewish hostility, lending support to the boycott of Jewish shops. The well-educated priest, Mykhailo Zubrytsky, advocated "economic antisemitism" — including the displacement of Jews from trade — as an instrument for achieving the modernization of Ukrainians.

Read more...

By the 1880s Polish Roman Catholicism had begun to identify the Jews as proponents of secularization and doctrines deemed hostile to Christianity (especially socialism). Similar attitudes penetrated Greek Catholicism by the early twentieth century.

sources

- John-Paul Himka, "Dimensions of a Triangle: Polish-Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Austrian Galicia," Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry, 12, Israel Bartal & Antony Polonsky, eds. (London/Portland, 1999), 43;

- Andriy Kuzmyak, "Economic tensions between Ruthenians and Jews at the end of the 19th century as depicted in the writings of fr. Mykhailo Zubrytsky," paper presented at the Congress of the European Association for Jewish Studies in Kraków, 2018;

- "Zubrytsky, Mykhailo," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (article updated 2020).

1879–1883

The Ukrainian newspaper Batkivshchyna (Fatherland), founded in Lviv on the initiative of Yuliian Romanchuk, promoted antisemitic views in a series of articles. The first editorial of the first issue declared that Ukrainians in Galicia had "two terrible enemies: one of them is the clever Jew, who sucks our blood and gnaws our flesh; the other is the haughty Pole, who is after both our body and soul." Galician authorities suppressed four of the first eight issues of Batkivshchyna for propagating hatred of the Jews. In later years, however, as president (from 1899 to 1907) of the National Democratic Party, Romanchuk rejected antisemitism and supported Jewish national autonomy within Austria-Hungary.

sources

- John-Paul Himka, "Ukrainian-Jewish Antagonism in the Galician Countryside During the Late Nineteenth Century," in Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective, Peter Potichnyj & Howard Aster, eds. (Edmonton, 1988), 112;

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. II, 139–140.

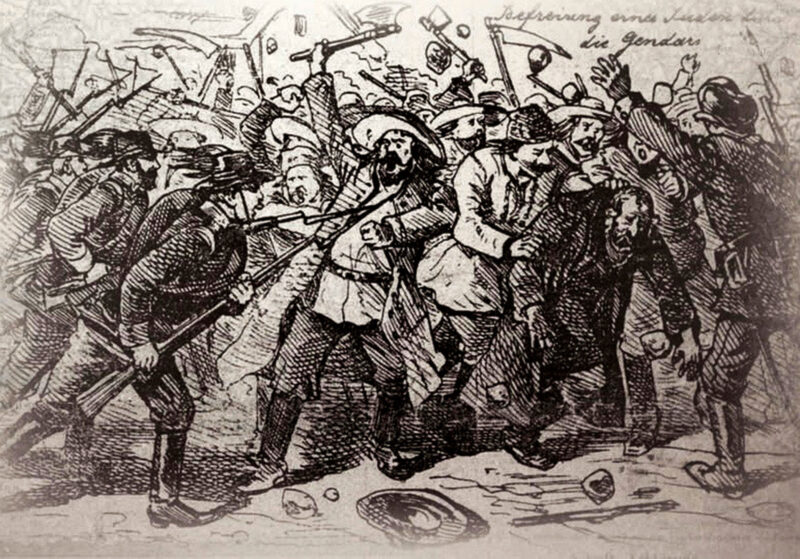

1898

Between February and June 1898, anti-Jewish violence erupted in 408 Galician communities — 21 in eastern Galicia, the rest in the western and central districts of the province. Bands of peasants broke into shops administered by Jews, bashing in windows and doors. They drank copious quantities of alcohol, shattered glasses, destroyed furniture, ransacked drawers, and attacked Jews with sticks and rocks. The primary objective of the attackers, joined by local townspeople, was to plunder, some loading their spoils onto carts driven into town for this purpose.

Read more...

No Jews were killed during the violence; at least eighteen rioters and bystanders were killed by the authorities in an attempt to restore law and order. By January 1899, prosecutors had charged 5,170 people. Most were Polish-speaking peasants, day labourers, miners, and railroad construction workers; there were also town council members, village leaders, teachers, and men and women of all ages. Galicia’s courts tried 3,816 people and sentenced 2,328 to prison terms lasting from a few days to three years. Relatively few Ruthenians/Ukrainians participated in the violence.

In his attempt to analyze the causes of the 1898 anti-Jewish riots and their aftermath, historian Daniel Unowsky found evidence of "a rural world rife with ignorance, drunkenness, and illiteracy, as well as medieval Catholic superstitions about the role of Jews in Host desecration, ritual murder, well-poisoning." However, Unowsky considers that the riots were not only a consequence of Galician backwardness. An additional critical factor was the arrival of modern political mobilization to the Galician countryside — in the context of suffrage reform, economic transformation, and efforts to harness popular political movements, using antisemitism as a tool.

As in other European countries at the turn of the century, antisemitism was openly expressed in Polish political culture, particularly after the emergence of the "National Democracy" movement (known from its abbreviation ND as Endecja) in the 1880s. This right-wing nationalist ideology became dominant also among the powerful Polish gentry in East Galicia, for whom modern political anti-Semitism became an enduring component of Polish patriotism. As Unowsky observes, "Polish peasant politicians would bring their interpretations of the 1898 violence into the newborn Poland after 1918: they argued that a modernization of the countryside that works for the benefit of Christians could come about only with the exclusion of the Jews."

sources

- Daniel Unowsky, The Plunder: The 1898 Anti-Jewish Riots in Habsburg Galicia (Stanford University Press, 2018), Introduction;

- John-Paul Himka, "Dimensions of a Triangle: Polish-Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Austrian Galicia," Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry, 12, Israel Bartal & Antony Polonsky, eds. (London/Portland, 1999), 37.