1370s–1430s

Initially, the Lithuanians tended not to disturb the existing religion and culture in the territories they conquered — a policy credited for their success, as summed up by one grand duke: "we are not introducing anything new, and we will not disturb what is old." As long as the Lithuanians remained pagan, they were, for the most part, tolerant toward the Orthodox Rus'. Some Lithuanian princes converted to Orthodoxy and protected the jurisdictional status of the Orthodox Church within their realm. However, policies changed after the conversion of Lithuanian Prince Jogaila/Jagiełło and his realm to Roman Catholicism in 1387. The conversion had favourable results for members of the Lithuanian nobility who converted to Roman Catholicism but negative repercussions for the vast numbers of inhabitants in the Grand Duchy who were Orthodox Rus'. These trends in the direction of religious intolerance and discrimination against the Orthodox Rus' eventually contributed to rebellions.

sources and related

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Ukraine: An Illustrated History (Toronto, Second Edition, 2007), 59–60;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 136–137, 139.

Related

Chapter 3.1 1340s–1500s

1450s

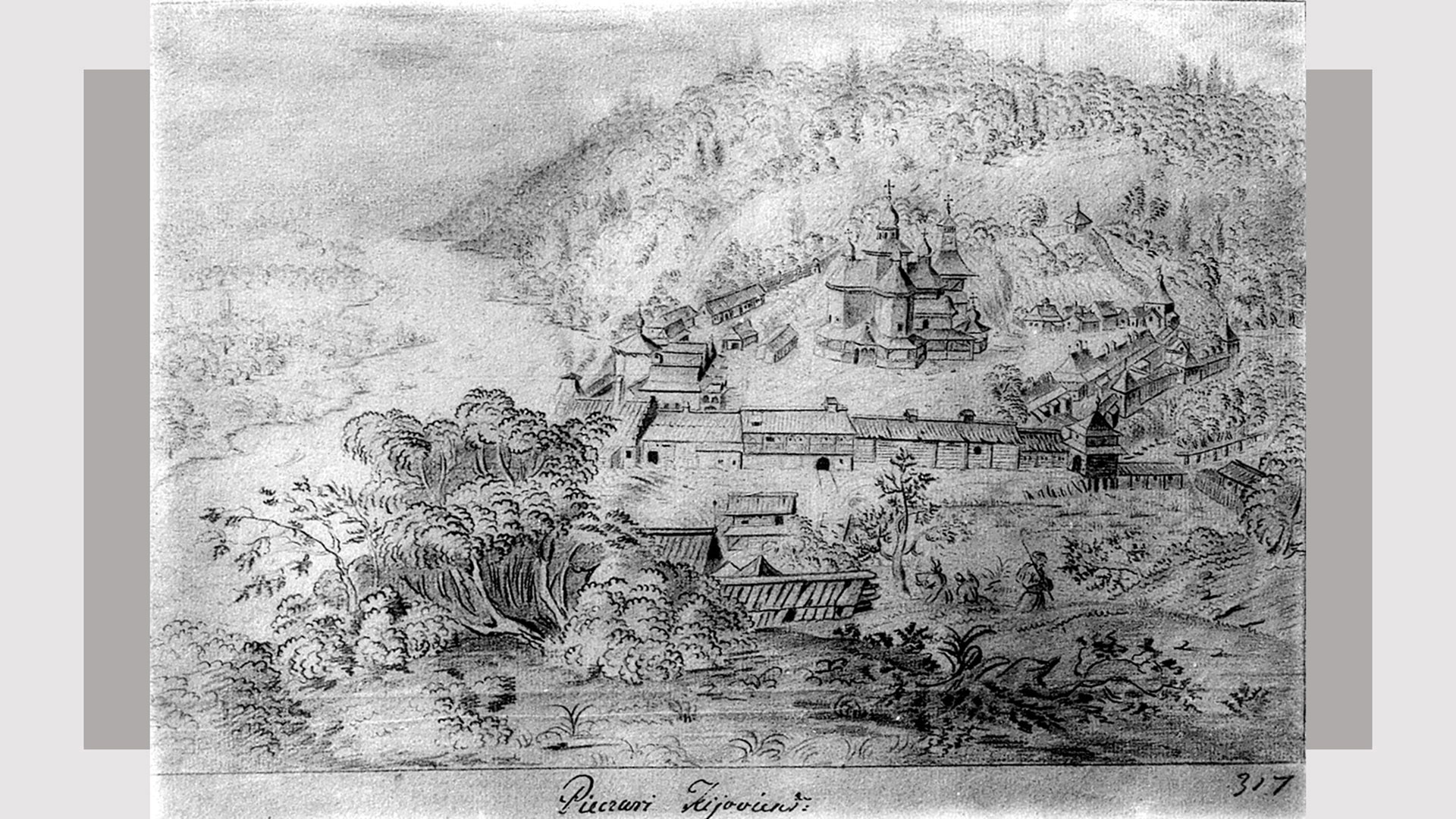

The Principality of Kyiv, an autonomous polity under semi-independent rulers from the Lithuanian dynasty, became an important intellectual center by the mid-fifteenth century. When the Ottoman Turks conquered Constantinople in 1453, politically stable and culturally reborn Orthodox Kyiv became a place of refuge for Christian and Jewish intellectuals leaving Byzantium.

sources

- Omeljan Pritsak, "The Pre-Ashkenazic Jews of Eastern Europe in Relation to the Khazars, the Rus' and the Lithuanians," in Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective, Peter Potichnyj & Howard Aster, eds. (Edmonton, 1988), 14–15.

1470s

According to sources from the period, a controversial but highly intellectual Christian sect called Judaizanti or zhidovstvuiushchie (Judaizers) by its foes had settled in Kyiv. Members of the sect, who likely had Jewish roots, held beliefs perceived as heretical by the Orthodox Church and adopted certain Jewish religious practices, such as observing the Sabbath. When their beliefs began to spread to Moscow, they were regarded as a threat to Russian Orthodoxy and banned.

sources

- Omeljan Pritsak, "The Pre-Ashkenazic Jews of Eastern Europe in Relation to the Khazars, the Rus' and the Lithuanians," in Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective, Peter Potichnyj & Howard Aster, eds. (Edmonton, 1988), 15.

1470s–1520

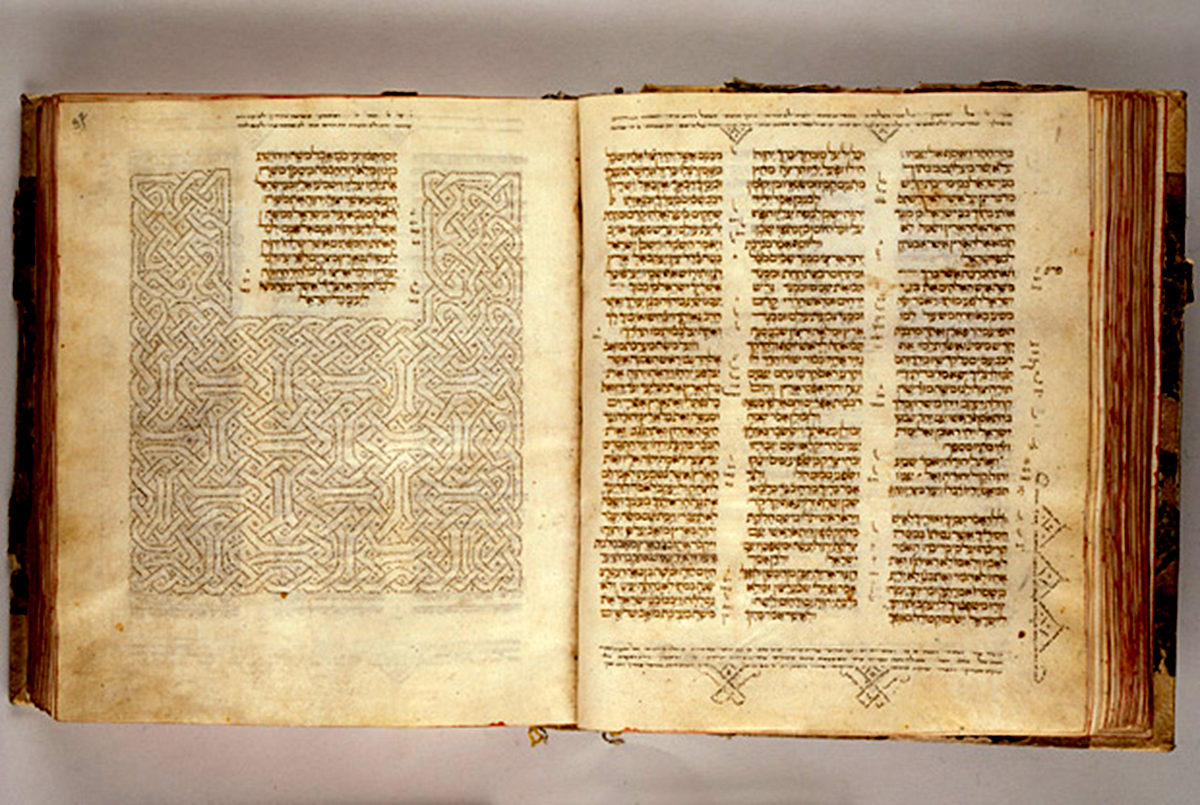

Moses ben Jacob (Moses of Kyiv II), a prominent Jewish scholar, was born, lived, and worked in Kyiv. A polymath scholar, he contributed to Biblical exegesis, Talmudic studies, Kabbalah, Hebrew grammar, and calendar formulation. His creativity was interrupted during the 1482 Tatar attack on Kyiv, when his library was plundered, and he was taken captive to the Crimea. He was soon ransomed and returned to Kyiv, but interrupted again in 1495, when Jews were expelled from Kyiv, then part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. During the last years of his life in Caffa/Kefe, he developed a new liturgical rite that came to be accepted by all traditional Jews of the Crimea.

sources

- Omeljan Pritsak, "The Pre-Ashkenazic Jews of Eastern Europe in Relation to the Khazars, the Rus' and the Lithuanians," in Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective, Peter Potichnyj & Howard Aster, eds. (Edmonton, 1988), 15.

1500s–1570s

Geopolitical developments since the late 1400s led to the isolation of Orthodox Christians on Ukrainian lands from their brethren in the faith in Muscovy, Constantinople, and Moldavia. Some responded to the isolation by withdrawing from the temporal world into the spiritual realm, fostering an increase in both new and restored monasteries. Monasteries, in turn, established schools and printing presses producing a variety of church books and religious literature. A small group of Orthodox Rus' magnates (such as Prince Kostiantyn Vasyl Ostrozky) became dedicated to raising the general level of their religiously based culture; they, too, established a network of schools and printing presses. For their part, Orthodox townspeople set up brotherhoods (bratstva) to support the social and educational interests of individual Orthodox parishes. The most important of the urban brotherhoods was the one associated with the Church of the Holy Dormition in Lviv. These developments reflect the considerable influence of the European Renaissance in Polish-ruled Ukrainian lands.

Read more...

The Polish nobility, then enjoying increasing economic wealth, experienced a cultural and religious renaissance, inspired by the Italian renaissance and the German and Czech religious reformation. The remarkable creativity of personalities of the Polish renaissance (such as astronomer Copernicus, poet Jan Kochanowski, and scholar of democracy Andrzej Frycz Modrzewski) and Poland's achievements in literature, scholarship, painting, sculpture, and architecture during this period enhanced Poland's reputation. Many Orthodox Rus' nobles were attracted to Polish culture, and in some cases, also to Roman Catholicism and the Polish political sphere.

The Counter-Reformation, launched by the Roman Catholic Church in reaction to the spread of the Protestant Reformation throughout Europe, reached Poland with the arrival of the Catholic Jesuit monastic order in 1564. Here, the Jesuits embarked on a polemical campaign directed not only at the Protestants but also the Orthodox. They set up Jesuit colleges (twenty-two on Ukrainian lands before 1648), Jesuit brotherhoods, and printing presses and succeeded in winning over converts to Catholicism. They also promoted the union of the Western (Roman) and eastern (Byzantine) churches. However, the actual initiative for church union came not from the Roman Catholics but rather from the Orthodox themselves. As perspectives changed, some Rus' magnates of Poland-Lithuania and Lviv's Stauropegial Brotherhood later became directly involved in the permanent division of the eastern-rite church in Ukraine.

One might reflect on the impact of growing divisiveness and religious zealotry (particularly on the part of the Jesuits) in shaping broader attitudes, including attitudes towards Jews.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Ukraine: An Illustrated History (Toronto, Second Edition, 2007), 73–78;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010) 157–166, 170–171.

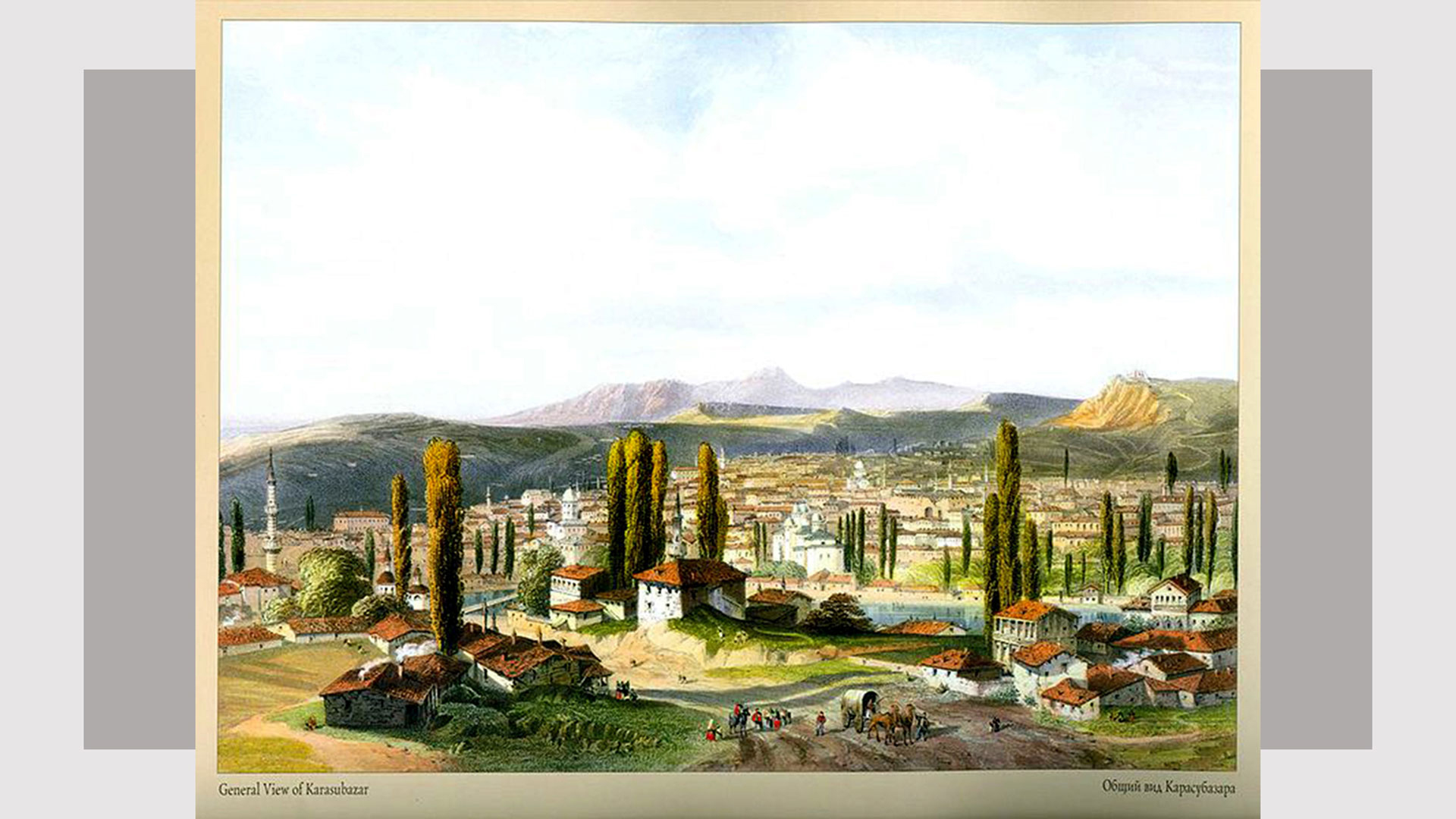

1500s–1783

The Crimean Khanate's Krymchaks and Karaites

The Crimean Khanate was a state governed by Islamic law, whose rulers and majority Tatar and Turkic population were Sunni Muslims. By the end of the sixteenth century, a small distinctive Jewish community emerged, that of the Krymchaks (Crimean Rabbanite Jews). The Krymchaks differed from all other Jewish communities, including the other small Crimean community with Jewish roots, the Karaites (who rejected rabbinic Judaism). The Krymchaks adopted the Crimean Tatar language for both speech and writing, using the Hebrew alphabet.

Read more...

By the seventeenth century, Chufut-Kale ("the Jews' Fortress" in Crimean Tatar) became a main center of the Karaites, described by some as a Karaite ghetto, especially after it received a large number of Karaite immigrants from Constantinople in the 1620s–1640s. Its inhabitants maintained contact with Karaite communities in Lithuania and western Ukraine (in Lutsk and Halych). Chufut-Kale was a flourishing Karaite cultural center in the eighteenth century, where books in Hebrew were printed and a Karaite Turkic literary language was fostered. That language used the Hebrew alphabet and later also the Cyrillic and Roman (Polish) alphabets.

The Muslim authorities of the Crimean Khanate tolerated both the Rabbanite Jews and the Karaites and differentiated between them as "Jews with earlocks" and "Jews without earlocks," respectively. However, discrimination prevailed against both. Until the Russian annexation of the Crimea in 1783, Jews and Christians (mainly Armenians and Greeks) were regulated according to the so-called Pact of Umar, which granted a degree of communal autonomy so long as certain (often humiliating) special obligations were fulfilled. Foremost among these was the requirement to pay a special poll tax, which was the source of a substantial portion of the khan's income. It was also forbidden for Jews to build houses and tombs higher than Muslim ones or ride on horseback. An especially humiliating duty — likely a local innovation as it was not part of the Pact of Umar — involved carrying Tatars across mud and slush.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, This Blessed Land (Toronto 2014), 41, 105–107;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Ukraine: An Illustrated History (Toronto, Second Edition, 2007), 182–184;

- Dan Shapira, "The First Jews of Ukraine," in Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry, Volume 26, Jews and Ukrainians, eds. Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Antony Polonsky (Oxford, 2014), 76–77;

- Michael Zand, "Krymchaks," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010);

- Golda Akhiezer, "Karaites," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).