1569–1600s

A new economic order emerged in Europe, which had profound implications for Ukrainians, Jews, and the evolution of Ukrainian-Jewish relations. In the new economic order, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth functioned as a supplier of raw materials to western European countries, with the grain trade as its most profitable sector. The primary beneficiaries of the thriving international trade were the Polish and Rus' (Ukrainian) nobles who established large estates on Ukrainian lands. To monetize these estates, they often engaged Jews as managers, using the arenda system of lease-holding. Jews thus became intermediaries between the nobles and the labouring peasant serfs.

Read more...

Polish and Rus' (Ukrainian) nobles, who had been granted extensive tracts of land (latifundia) in the newly acquired Ukrainian territories, established large manorial estates (filvarky) and either owned or controlled various enterprises mostly related to the new economic order. As they had neither the capacity nor interest in administering these estates and enterprises on their own, they turned to the so-called arenda or lease-holding system. The arenda system enabled them to lease to individual managers their fixed assets, such as grain mills, breweries, distilleries, manorial farms, and even the right to collect taxes and customs duties in their name. Their preferred managers were Jews, not only because they believed Jews had economic skills but also because Jews were less likely to acquire political power and challenge their noble patrons than Christian townspeople.

As leaseholders, Jews paid cash for land use or the exercise of the landowners' various monopoly rights; any income made beyond the cost of the leasehold would be their profit. As servitors of the Polish and Ukrainian landowners, however, the Jewish leaseholders were also liable to be depicted, in the words of historian Simon Dubnow, as "sponges to convey the wealth of the country and the toil of its inhabitants into the pockets of the lords."

Jews were also invited to settle and develop the economy in the nobles' private towns, where they engaged in trade (specializing in textiles, skins, furs, wax, lead, and salt) and crafts (as furriers, tanners, and tailors). They also served as haberdashers, butchers, and bakers. Offering goods and services, they became active in the local marketplaces, connecting the towns to the hinterland.

At the same time, more severe demands were made of the Ukrainian peasantry, increasingly reduced to serfdom. After the Union of Lublin, the Polish magnates and nobles extended to Ukrainian lands feudal practices prevalent in Poland, based on legislation they had won over decades, which gave them complete autonomy in managing their landed estates. The amount of labour demanded of the serfs and all other matters affecting them were left to the decision of the nobles, their tenants, or their stewards. Compensation to the nobles for the strips of land worked by the serfs usually took the form of obligatory unpaid labour (corvée). Historians have contrasted the arbitrary nature of this arrangement with the uniform system of serf obligations and relations maintained on the royal estates, where serfs generally received better treatment than on the private noble estates. As the burden and exploitation of the peasants increased, some fled to the territories under Cossack control and joined the Cossack uprisings.

sources and related

- Judith Kalik, "Leaseholding," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010);

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 151–156;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Ukraine: An Illustrated History (Toronto, Second Edition, 2007), 67–71;

- Adam Teller and Igor Kakolewski, "Paradisus Iudaeorum, 1569–1648," Polin: 1000 Year History of Polish Jews (Warsaw, 2014), 115–116, 118.

Related

Chapter 3.1 1539

Chapter 3.3 1400s–1500s (Read More)

Chapter 4.5 1637–1639

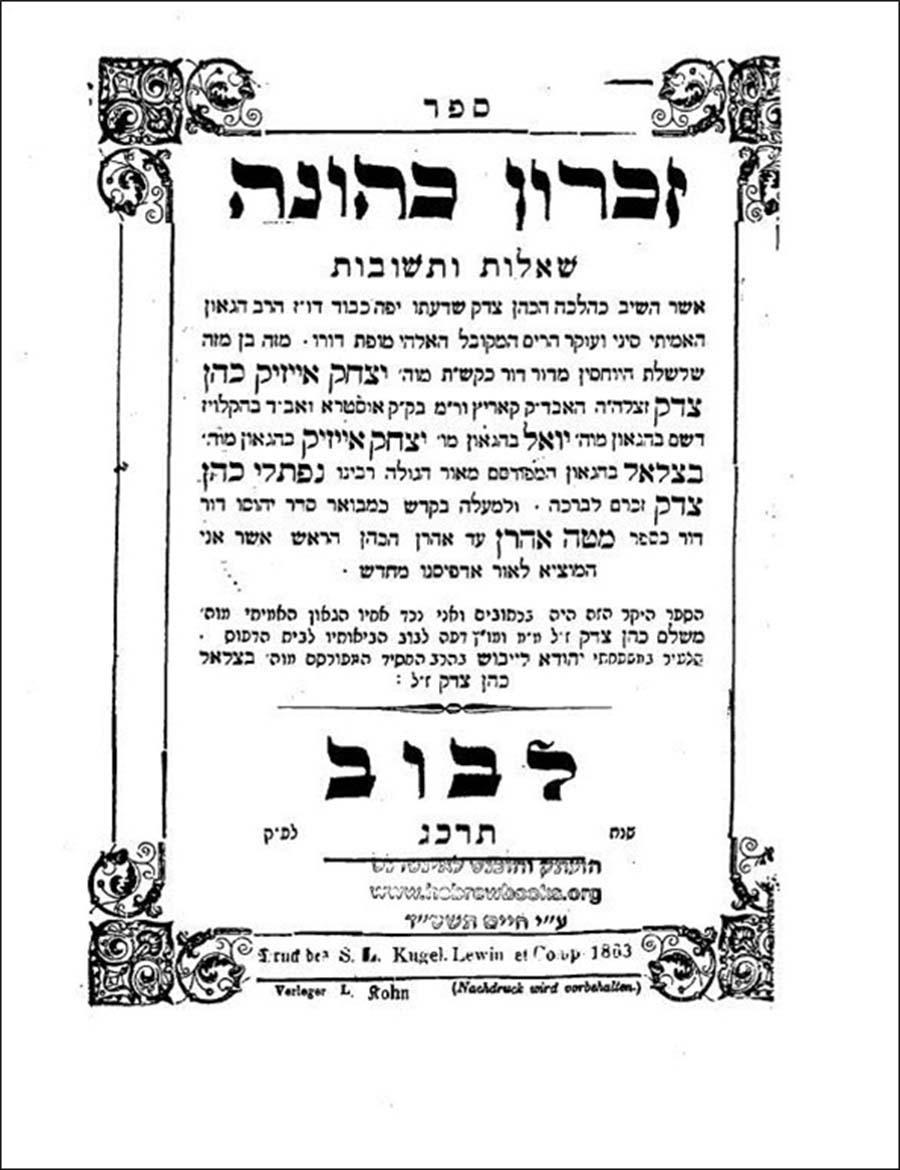

1580s–1690s

Rabbinic responsa literature (responses to queries from individuals relating to specific issues in Jewish law) and town documents from this period indicate that Jews in some localities enjoyed specified civic and economic liberties granted by the Polish crown. A royal edict of 1580, for example, demanded that the burghers of Lutsk give local Jews a share of their "liberties" (economic privileges) since the Jews contributed money to the town to pay for these privileges. Jews were also represented in the autonomous organization of towns and cities, and their artisans could establish guilds. There is a reference, for example, to a Jewish tailors' guild in Żółkiew/Zhovkva in 1693. In their desire to encourage Jewish merchants and entrepreneurs to settle in their private towns, nobles offered privileges to the Jewish communities, such as economic rights, freedom to practice their religion, and protection from the animosity of Christian burghers resenting competition. Zhovkva's rapidly growing Jewish community (90 families in 1680, a third of the population) soon came to rival nearby Lviv as a leading center of Jewish life in the Commonwealth.

sources

- Shmuel Ettinger, "Jewish Participation in the Settlement of Ukraine in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries," in Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective, Peter Potichnyj & Howard Aster, eds. (Edmonton, 1988), 28;

- Adam Teller, "The Jewish Town, 1648–1772," Polin: 1000 Year History of Polish Jews (Warsaw, 2014), 116, 130–132.

1660s–1730s

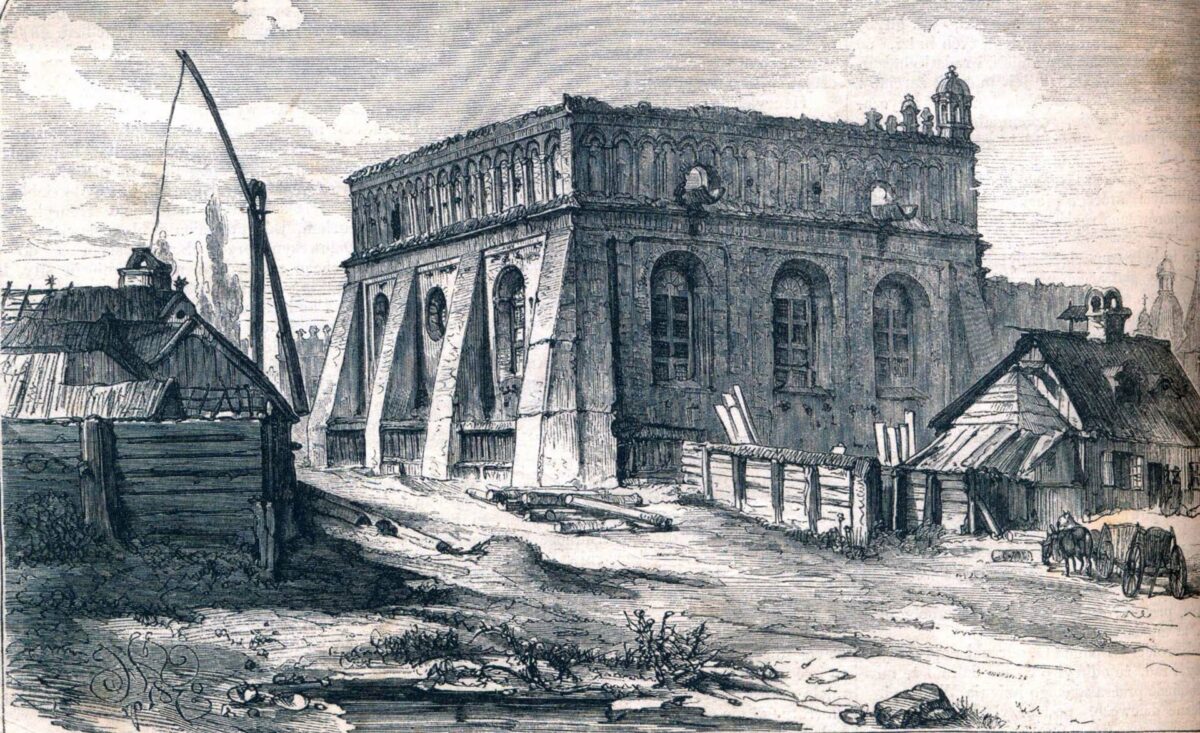

In response to local pressure, Lviv's Polish city officials initiated lawsuits and disputes with the Jewish community about the ambit of economic and residential restrictions. The disputes generally revolved around the implementation of royal decrees, often contradictory, relating to housing permitted to Jews or governing the economic activities of Jews — particularly in retail trade, the crafts, the sale of liquor, and the operation of wax refineries. Often, restrictive royal decrees were not enforced.

sources

- Myron Kapral, "The Jews of Lviv and the City Council in the Early Modern Period," in Polin Studies in Polish Jewry, Volume 26, Jews and Ukrainians, eds. Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Antony Polonsky (Oxford, 2014), 84–92.

1670s–1680s

Polish King Jan Sobieski entrusted his "factor" (agent/trustee) Jakub Bezalel ben Nathan, one of the wealthiest Jews in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, with the responsibility for the collection of all royal tariffs in Podolia and Ukraine.

1700s

Lviv continued to be an important center in the trade of luxury goods with the East, with Jews dominating trade with Turkey and Armenians preeminent in trade with Persia. Jews from Ukrainian lands were also prominent in overland trade with Germany and other central and west European countries, facilitated by their participation in the Leipzig fairs.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford and Portland, OR, 2010), vol. I, 110.

1700s

Leasing certain monopoly rights became the backbone of the Jewish economy in the Ruthenian/Ukrainian lands of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. A 1753 census indicates that more than one-third of employed Jews were leaseholders of various kinds. These included milling, fishing, forest produce, the sale of salt and tobacco, and especially the propinacja — the exclusive right to produce, distribute, and sell alcoholic beverages. Nobles preferred to entrust the production of alcohol — a key source of their revenue — to Jews who had the capital for development and who were judged disinclined to consume it to excess themselves. Jews thus came to play a key role in the alcohol trade in the region on behalf of their lessors, including as managers of inns and taverns in the case of Jews of modest means. The fact that there were so many Jews producing and selling alcohol influenced relations both within the Jewish community and between Jews and Christians, especially burghers displaced from the sector and others resentful of an economic system run along feudal lines. In addition to being engaged in distilling and innkeeping, Jews who lived in villages were sometimes farmers, particularly dairy farmers, or involved in milling and small-scale credit provision.

sources

- Shmuel Ettinger, "Jewish Participation in the Settlement of Ukraine in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries," in Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective, Peter Potichnyj & Howard Aster, eds. (Edmonton, 1988), 28;

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford and Portland, OR, 2010), vol. I, 89, 101;

- Judith Kalik, "Leaseholding," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010);

- Jacob Goldberg, "Tavernkeeping," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2014).

1768–1800s

The Polish sejm passed a resolution in 1768 forbidding Jews to keep inns and taverns without special permission from the local municipality. This resolution seems to have been largely ignored by the noble landowners reluctant to lose their income from these sources. However, continued attacks on the role of Jewish innkeepers eventually had some effect. One estimate indicates that as many as half of all Ukrainian inns passed from Jewish into non-Jewish hands between 1765 and 1784. Also, at the Four-Year Sejm (1788–1792), the idea of rescinding Jews' rights to lease taverns and breweries was incorporated into draft legislation for the social and cultural reform of the Jews.

Read more...

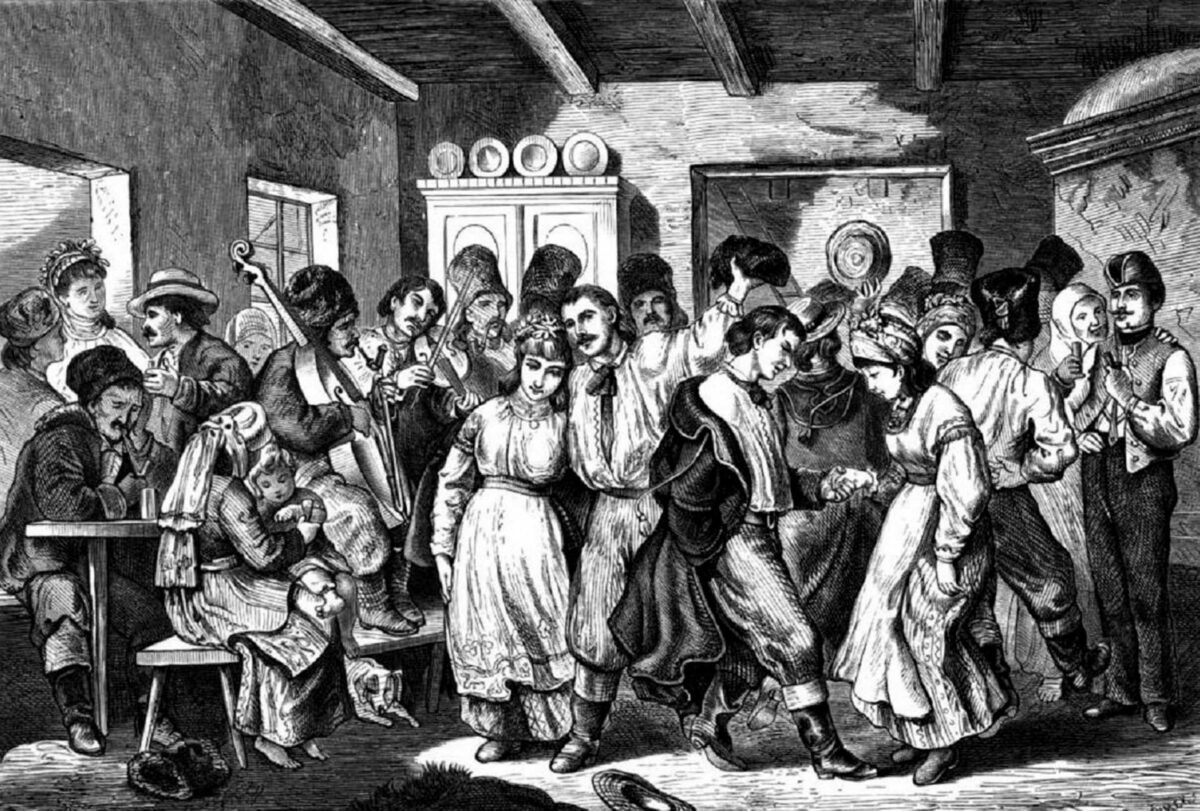

Reformers and government officials in the nineteenth century continued to blame Jewish tavernkeepers for poverty and alcoholism in rural areas and sought to drive Jews out of the liquor trade. They tended to overlook the vital role of inns and taverns as social and hospitality venues where celebrations and even religious festivities were held and as meeting places where community business was conducted, politics discussed, and advice received about medical remedies and other matters.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford and Portland, OR, 2010), vol. I, 101, 209–210;

- Glenn Dynner, Yankel's Tavern: Jews, Liquor, and Life in the Kingdom of Poland (Oxford, 2013).