1780s–1800s

Galicia

Empress Maria Theresa and her son Joseph II introduced measures to raise the status of the previously somewhat oppressed Greek Catholic majority in Galicia. The Empress renamed the confession Greek Catholic (rather than Uniate) to symbolize equality with the Roman Catholic church. In 1784 they established a university in Lviv and created a general seminary there to train Greek Catholic priests. In 1808 they re-established the Greek Catholic metropolitanate of St. George in Lviv.

The thrust of the measures adopted towards Jews — ranging from integrationist to assimilationist — were widely perceived as undermining traditional Jewish religious and community life.

Read more...

Measures introduced to "integrate" Jews culturally include compulsory German-language primary education and access to higher learning; adoption of German surnames to enable mandatory recordkeeping of vital records; and declaring Jewish marriages to be civil contracts requiring government-issued certificates. At the same time, the authorities required normal-school certification and civilian marriage certificates as prerequisites for engaging in certain occupations, including the rabbinate.

More ruthless assimilationist measures included the abolition of the traditional Jewish system of local self-government (1785) and the authority of rabbinical civil law, which had previously governed the community, and Jewish military conscription (1788) without provision for the observance of religious practices.

While some segments of Galician Jewry, in particular the proponents of the Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment) movement, welcomed the integrationist reforms, the traditional majority of Galicia's Jewish population regarded such reforms as undermining Jewish religious and cultural life.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 420;

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. I, 251–254.

1780s–1790s

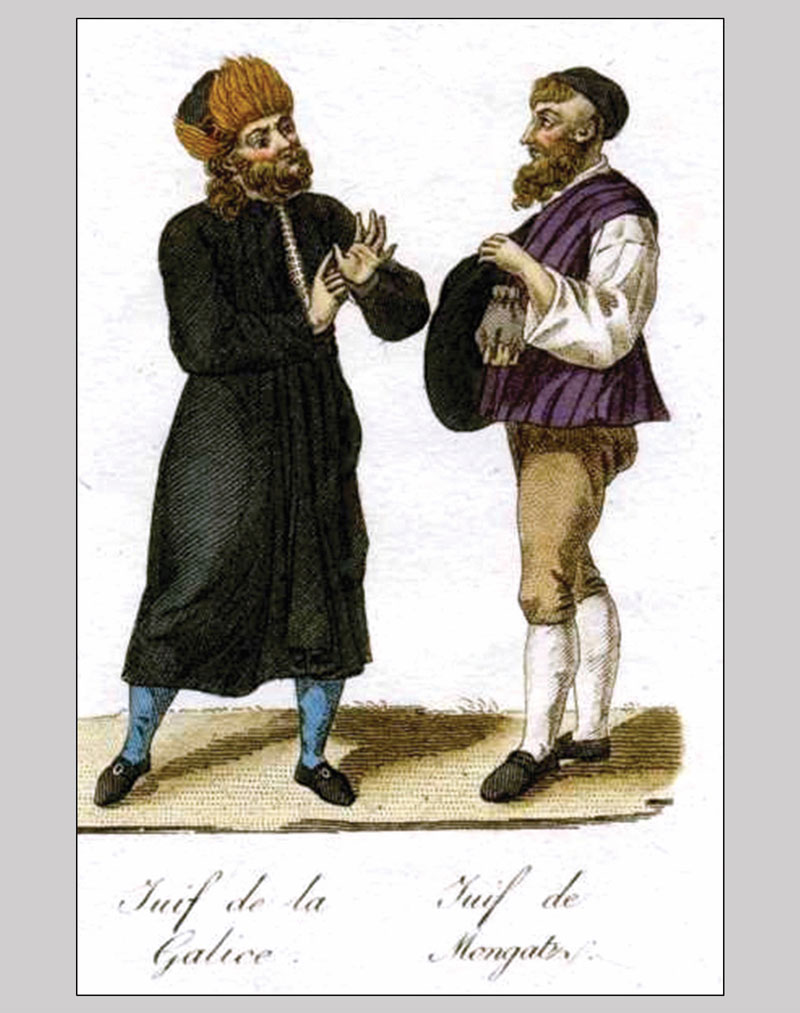

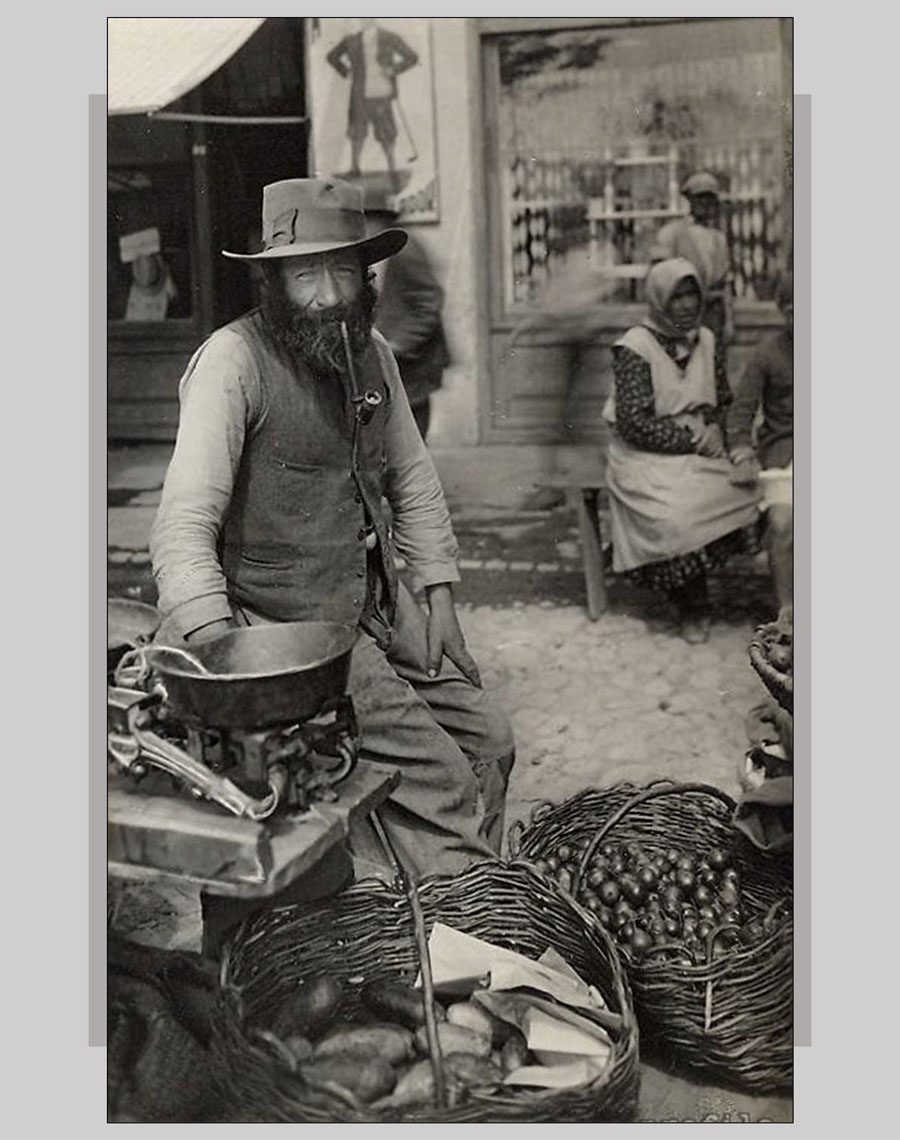

Ber Birkenthal's memoirs vividly depict Jewish life in Galicia, both before and during Austrian rule. On the one hand, they reveal aspects of society, as perceived by a Jewish merchant during his adventurous and arduous wine-buying journeys from Galicia to Hungary, including experiences of flea-infested inns and attacks by robbers. On the other hand, they shed light on a stratum of enlightened, worldly Jews living on these territories during this period. Birkenthal was tutored in Polish, Latin, French, and German from an early age and was well-read. He believed that these assets enabled him to intercede with the noble landlords and the authorities on behalf of the Jewish community to make the case against unfair economic treatment and dangerous slander, such as the blood libel. Both in his memoirs and in "Divre binah" (Words of Wisdom; unpublished, ca. 1780–1800), Birkenthal discussed the Sabbatian movement and Frankist sectarianism, including his role as a translator at the 1759 public disputation between the Frankists and the Jewish community. His memoirs also provide insights into local political intrigue, trade relations between neighbouring towns, friendships with other Jews and non-Jews, and the circumstances under which the town of Bolechów/Bolechiv was burned down.

sources

- Ruth Ellen Gruber; Nancy Sinkoff, "Ber of Bolechów," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1790s–1800s

Bukovina

Under pressure from the authorities, the first German-language Jewish schools were established in Bukovina. The acquisition of bourgeois values and the study of German language and culture stimulated the assimilationist enthusiasm of the Jewish urban class, which focused on social mobility and rapid integration into the broader society. More common folk retained their attachment to Jewish orthodox traditions, especially Hasidism, which attracted numerous adherents in Bukovina.

sources

- Andrei Corbea-Hoisie, "Bucovina," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1787–1819

The Haskalah in Galicia

Herz Homberg and Joseph Perl were among the most prominent supporters of the Austrian regime's policy of imposing enlightenment and integrating Jews through educational reforms. Both were influenced by Naftali Herz Wessely (1725–1805), the Prussian-born proponent of secular humanistic education for Jews, as set out in his 1782 pamphlet, Divrei shalom ve'emet (Words of Peace and Truth). Both Homberg and Perl also pennedfierce critiques of the Hasidic movement.

Read more...

Homberg worked closely with the authorities as supervisor of the German Jewish school system in Galicia and founded around 100 schools. His ambitious program of coercive educational reform according to Haskalah-inspired norms, in addition to his role as assistant censor of Jewish books, did not endear him to traditional Jews. Most Jews tried to avoid sending their children to these schools, which they regarded as instruments of assimilation and conversion to Christianity. Homberg was ruthless in denouncing to the authorities religious Jews who refused to comply with the requirements he formulated. Following rumours and scandals, the Austrian authorities abrogated this school system by 1806.

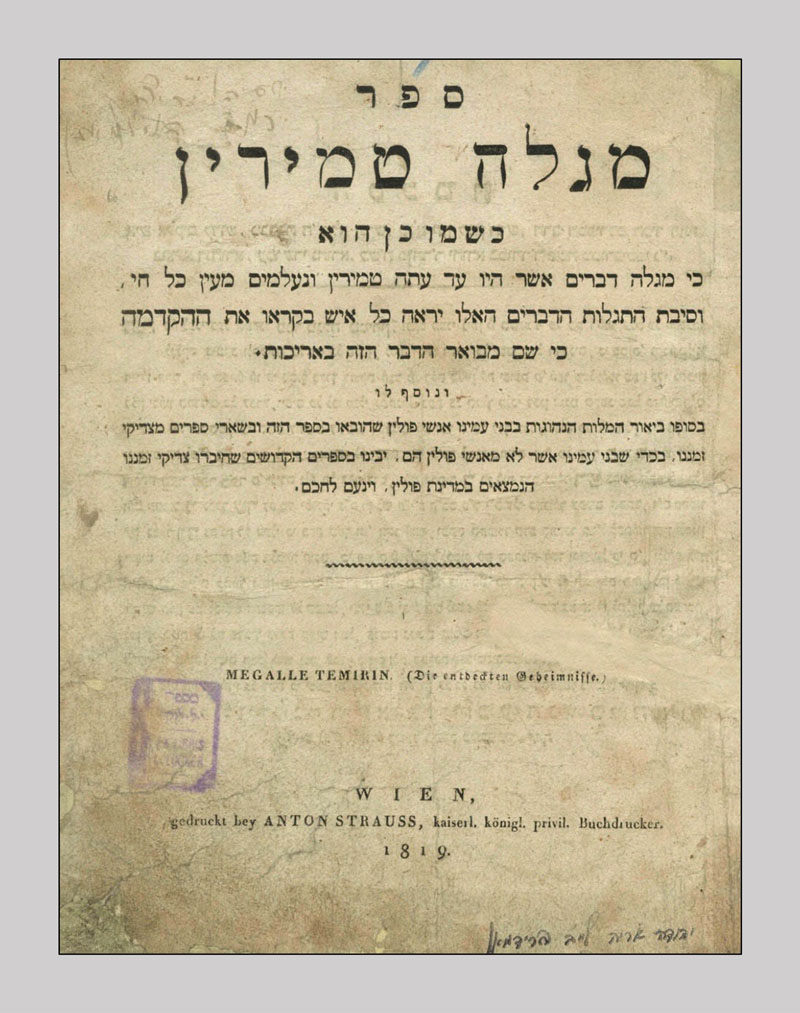

In 1813 Joseph Perl established the first Jewish school based on the principles of the Haskalah in Ternopil (then under Russian rule). The school prospered in the following decades when Austria ruled the area. Following the 1806 closure of German-language schools for Jews, Perl and other Jewish reformers revitalized a network of modern Jewish schools in Galicia. By the 1850s, Jewish state schools, both primary and secondary, based on Haskalah principles and generally using German as the language of instruction, were functioning in fourteen towns, including Lviv, Brody, and Przemyśl, with some 3,000 students attending. Perl's creative literary works, such as Megaleh temirin (The Revealer of Secrets), published in Vienna in 1819, opened up the genre of anti-Hasidic satire among proponents of the Haskalah. His activism also led to restrictive laws governing Hasidic prayer groups and police searches that resulted in the confiscation of "forbidden" Hasidic books.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. I, 255;

- Riety van Luit, "Homberg, Herz" and Jonatan Meir, "Perl, Yosef," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1804

Jakob Rappaport, the first Jewish physician to graduate from Lemberg University, went on to manage a successful medical practice in Lemberg for four decades. His services, which crossed ethnic and religious boundaries, included tending to the sick during the 1831 cholera epidemic. Rappaport was also an influential member of the local Jewish community, and in 1840 lent his support to the establishment of Lemberg's Reform synagogue.

1809

Cultural Revival among Transcarpathia's Ukrainians

Bishop Andrei Bachynsky, a prominent figure of the Enlightenment, ushered in a national, religious, cultural and economic revival for Carpatho-Ukrainians (Ruthenians). His efforts contributed to the establishment of elementary schools in every parish church. In the sphere of higher education, a college for the training of teachers and a theological seminary for the education of Ruthenian priests, where some courses were taught in the Ruthenian language, were established in Uzhhorod.

sources

- Alexander Baran, "Jewish-Ukrainian Relations in Transcarpathia," in Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective, Peter Potichnyj & Howard Aster, eds. (Edmonton, 1988), 161–162;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, The People from Nowhere: an illustrated history of Carpatho-Rusyns (Uzhorod, 2006), 50.

1815–1867

Hasidism in Galicia

While Podolia and Volhynia were the cradles of Hasidism until 1772, by 1815, the center of gravity of the movement had significantly shifted to Galicia. During this period, at least 26 major Hasidic centers emerged in the Austrian-ruled province. In the decades after 1815, there were further remarkable transformations in the geography of Hasidism, as the movement began to expand to Hungary and Romania and gained absolute dominance in Galicia by the mid-nineteenth century.

Adherents of Hasidism during this period continued to encounter opposition from traditionalist religious Jews (the misnagdim, literally "opponents"); they were also disdained and satirized by the modernist proponents of the Jewish enlightenment (the maskilim).

Many more tsadikim (Hasidic leaders) had set up their "courts" or compounds in Galicia than in any other area in Eastern Europe. A typical Hasidic court would accommodate the family of the tsadik, a permanent staff, and a resident circle of the closest disciples. While some courts were luxurious, most were very modest.

Read more...

The majority of Hasidim lived at a distance from their leader, whose court they would visit only on special occasions. For the rest of the year, local adherents of a particular leader (or several leaders) would pray, study, and fraternize in one or more small local prayer houses called shtiblekh (sing. shtibl).

Among the most influential Hasidic dynasties in Austrian-ruled Galicia and Bukovina (as measured by the number of shtiblekh associated with them) were those established in Belz, Chortkiv, Sadagura/Sadhora (Yid. Sadigura), Husyatin, and Vizhnitz/Vyzhnytsia. In his detailed study of the expansion of Hasidism, Marcin Wodziński suggests two models: the nuclear model in which each tsadik builds his own network of influence, and the dynastic model, exemplified by Sadagura's Friedman dynasty, in which interrelated tsadikim from one dynasty divide territory among themselves.

Hasidism also expanded during this period in regions that today are part of Poland, Russia, Transcarpathia, and Romania. Although Hasidism largely transcended political boundaries, the varieties that evolved under Habsburg rule differed from those that emerged in tsarist Russia and the Congress Kingdom of Poland. The differences manifested in the patterns of leadership, literary legacies, responses to modernity, and openness to cross-cultural borrowing (particularly of songs and melodies) from neighbouring peoples.

sources and related

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. I, 258;

- Marcin Wodziński, Historical Atlas of Hasidism (Princeton University Press, 2018), 38–40, 91–93, 107, 118–122;

- David Assaf, "Hasidism: Historical Overview," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

Related

Chapter 4.4 1742–1790s (Read More)

Chapter 6.4 1790s–1820s

1830s

The Ukrainian National Awakening

Three Galician writers — Markiian Shashkevych, Yakiv Holovatsky, and Ivan Vahylevych — published Rusalka Dnistrovaia (The Nymph of the Dniester), an anthology of Ukrainian folklore that used the Ukrainian vernacular and a simplified form of the Cyrillic alphabet for the first time in Austrian Galicia. The collection, which included folkloric texts, translations from European literature, and philological studies, frightened the Habsburg authorities, who perceived the innovation in language and alphabet as a threat to the established social order. The works of these writers contributed significantly to a cultural-national awakening among Ukrainians in Galicia.

The initiators of the Ukrainian national awakening under Habsburg rule were mostly priests or the sons of priests of the Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church, in contrast with the national awakeners in tsarist Russia, who were mostly the offspring of Cossacks of the Orthodox faith. This trend continued after Austria introduced a constitution, limited suffrage, and civil freedoms in 1867.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence (Toronto, Second Edition, 2018), 88–89.

- John-Paul Himka, Ten Turning Points: A Brief History of Ukraine.

1840s

Jewish modernists vs traditionalists

The conflict between the supporters and opponents of Jewish integration into the broader society intensified, especially with respect to education and religious reform. It was particularly bitter in Lviv, which had a large Orthodox and Hasidic population, alongside the Westernized Jewish minority. Many Jewish youths began to attend German schools, much to the dismay of the Orthodox. In 1844 a modern synagogue, the Deutsch-Israelitisches Bethaus, was established in Lviv. Its first rabbi, Abraham Kohn, was poisoned in 1848 by an Orthodox fanatic. Despite the advances made by the Haskalah in Galicia, it was the Hasidic movement that became the dominant way of life of Galician Jewry.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. I, 260–261;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 420.

1848–1851

The year 1848 witnessed a surge of significant achievements in the Ukrainian cultural realm, including a remarkable increase in Ukrainian-language publications and the creation of organizations and societies promoting Ukrainian scholarship, education and popular culture. The establishment of a Ukrainian "National Home" in Lviv under the auspices of the Supreme Ruthenian Council eventually led to the construction of a new center in 1864, which included a museum, a printing shop, and a library and the first Ukrainian professional theatre.

Read more...

A critical and enduring development for Ukrainian scholarship and education was the Imperial government's decision in December 1848 to establish a Department of Ruthenian Language and Literature in the faculty of philosophy at the University of Lviv — the Department functioned until 1939.

Forty-two Jewish students enrolled at the University of Lviv in the faculties of law and philosophy in 1851.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 439–440;

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. I, 255.

1700s–1870s

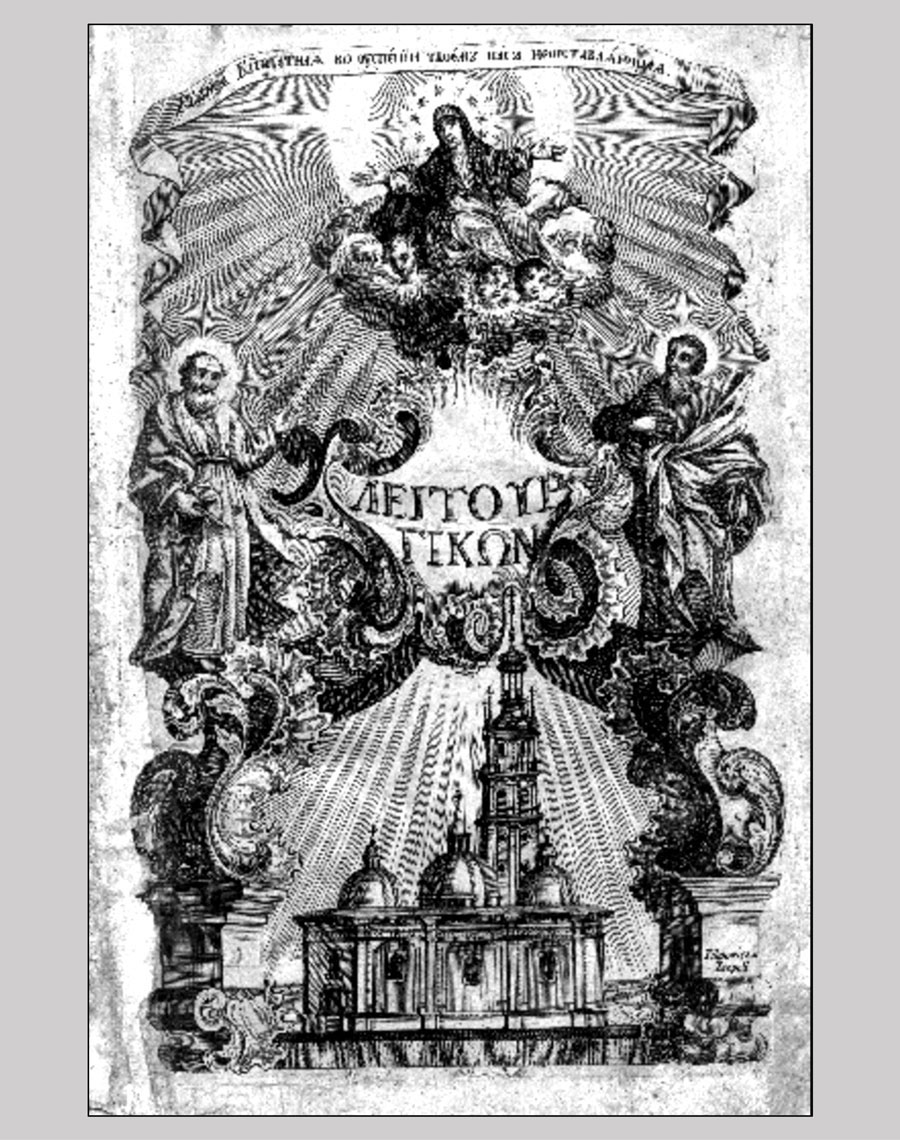

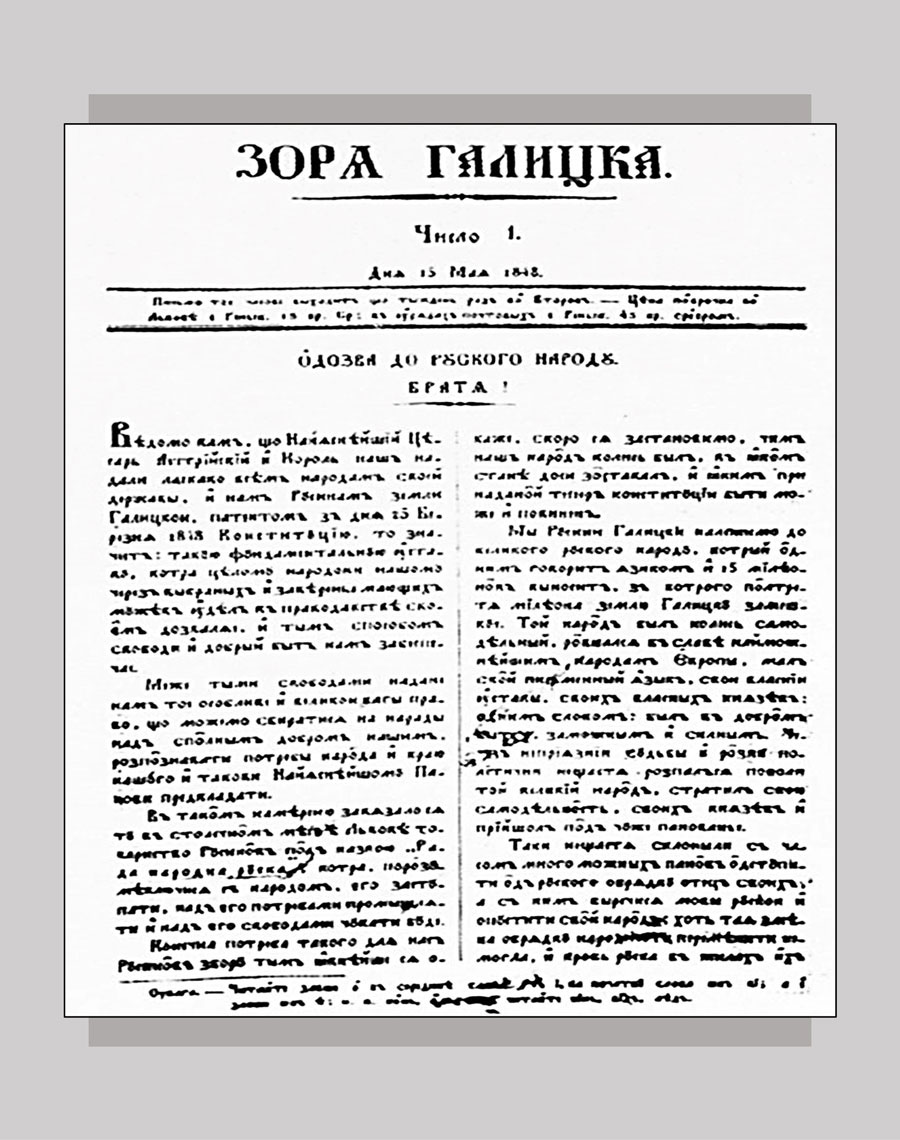

Ukrainian printing

Lviv was a key center of book production and printing in the Cyrillic alphabet two centuries before Austria annexed Habsburg Galicia. The first Cyrillic press in Ukrainian lands was established in the 1570s in Lviv by Ivan Fedorov (who later founded the famous printing press in Ostroh). After that, Lviv became a significant printing center also for Polish, Armenian, Cyrillic and Hebrew/Yiddish presses.

Securing Cyrillic typefaces was a challenge in Polish-ruled lands where the Roman or Latin alphabet was the norm. An additional challenge emerged in the early eighteenth century when Russian Tsar Peter I introduced a revised, simpler Cyrillic civil script, which eventually became the standard for all publications other than church books.

Read more...

Challenges notwithstanding, printing and publishing represented a remarkable achievement of the Galician Ukrainian national movement in the mid-nineteenth century under Austrian rule. The first Ukrainian newspaper, Zoria halytska, was published from May 1848 to 1857, and a number of other Ukrainian journals were launched in Galicia and Bukovina at the time of the Springtime of Nations revolution. As for books, in 1848 alone 156 titles appeared, almost five times as many as in every previous year, and in stark contrast with Ukrainian lands under tsarist rule, where in the same year only one book and a few pages in two other books appeared in Ukrainian. Also remarkable is that most of these publications appeared in the Galician-Ukrainian vernacular, though using the Church Slavonic alphabet.

The wide dissemination of books, journals, pamphlets, and newspapers had practical national and social implications as the main instruments for preserving and promoting the Ukrainian language, culture, and identity. And so, in the relatively tolerant atmosphere of late-nineteenth-century Habsburg-ruled Galicia, Ruthenian cultural and civic organizations sought to produce their publications in large quantities, with some books having print-runs up to 100,000 copies.

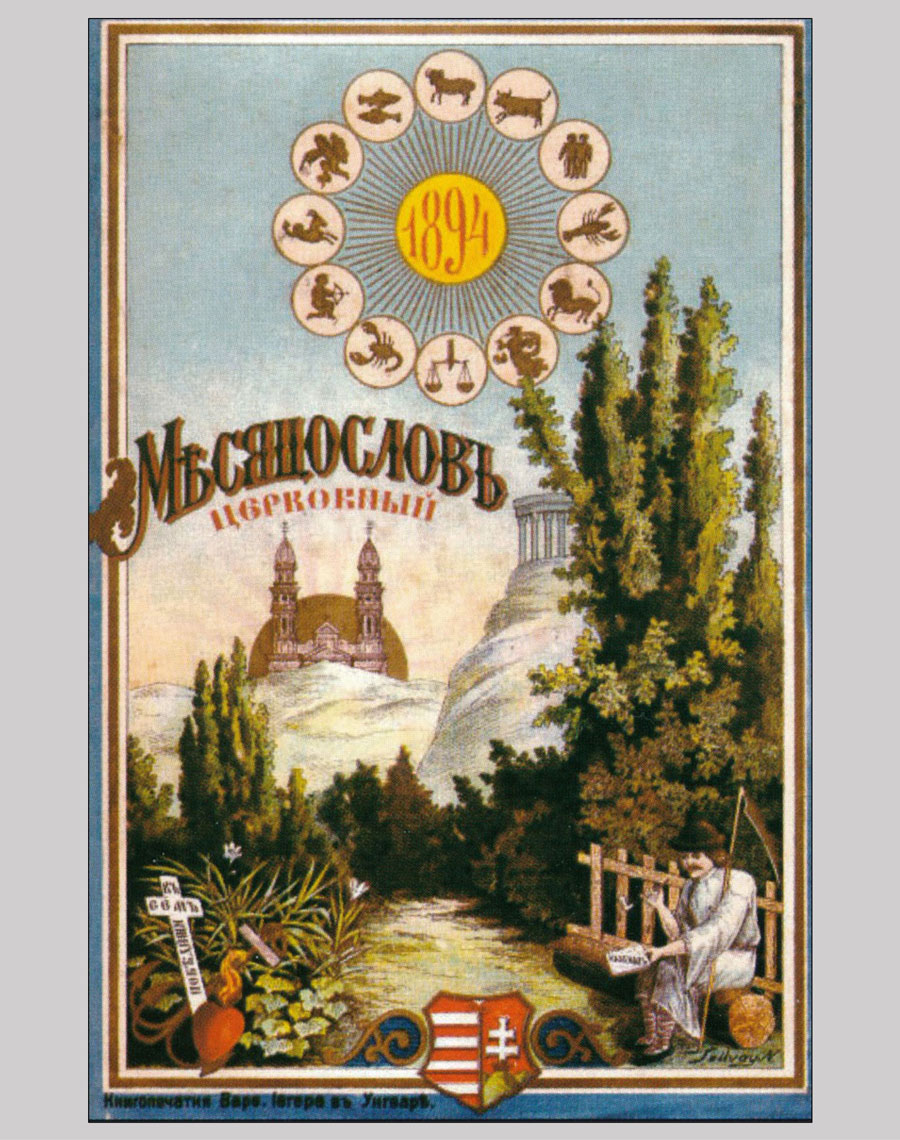

The prohibitive conditions for Ukrainian publications in tsarist Russia after 1863 contributed to Galicia (and Lviv in particular) becoming the center of Ukrainian book publishing. In 1875 more books were published in Galicia (62, 42 of them in Lviv) than in all of Russian-ruled Ukraine. In 1894, 177 books were published in Galicia (136 in Lviv), compared to 30 in eastern and central Ukraine. Russian censorship eased somewhat after the 1905 Revolution, enabling the publication of 246 Ukrainian-language books in 1913. That same year 326 books appeared in Galicia (238 in Lviv). Thus, Galicia maintained its status as the leading producer of Ukrainian books until the First World War.

Bukovina had ready access to Galician publications. Nonetheless, local publishers began to produce general educational literature and belles lettres in Ukrainian in the 1870s. By 1918 they published about 270 titles. In Transcarpathia, Ukrainian publishing developed later — four books were published there in 1875, three in 1894, and 22 in 1913.

sources and related

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 435, 439–440;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence (Toronto, Second Edition, 2018), 153–155;

- "Printing," "Book publishing, "Univ," "Zoria halytska," and "Museum of the Book and Printing of Ukraine," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine.

Related

Chapter 4.4. 1560s–1600s

1780s–1870s

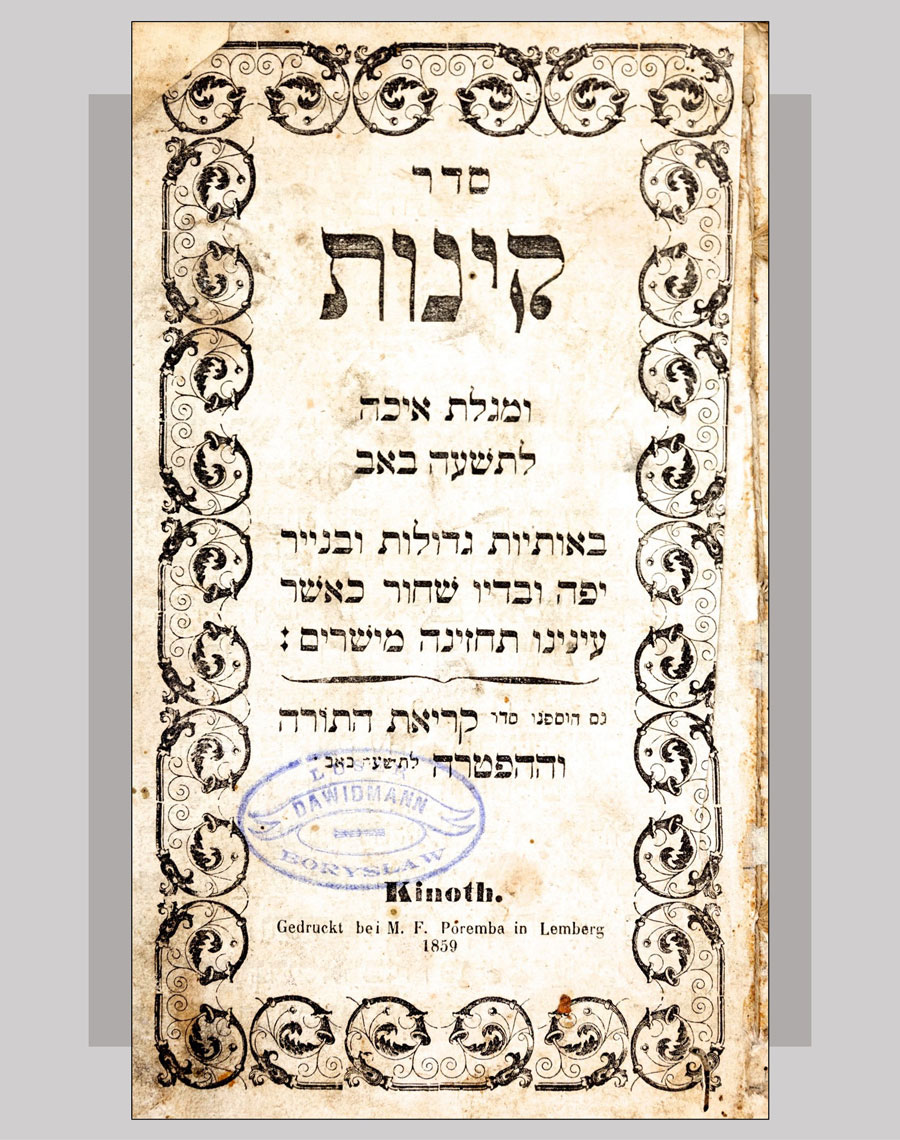

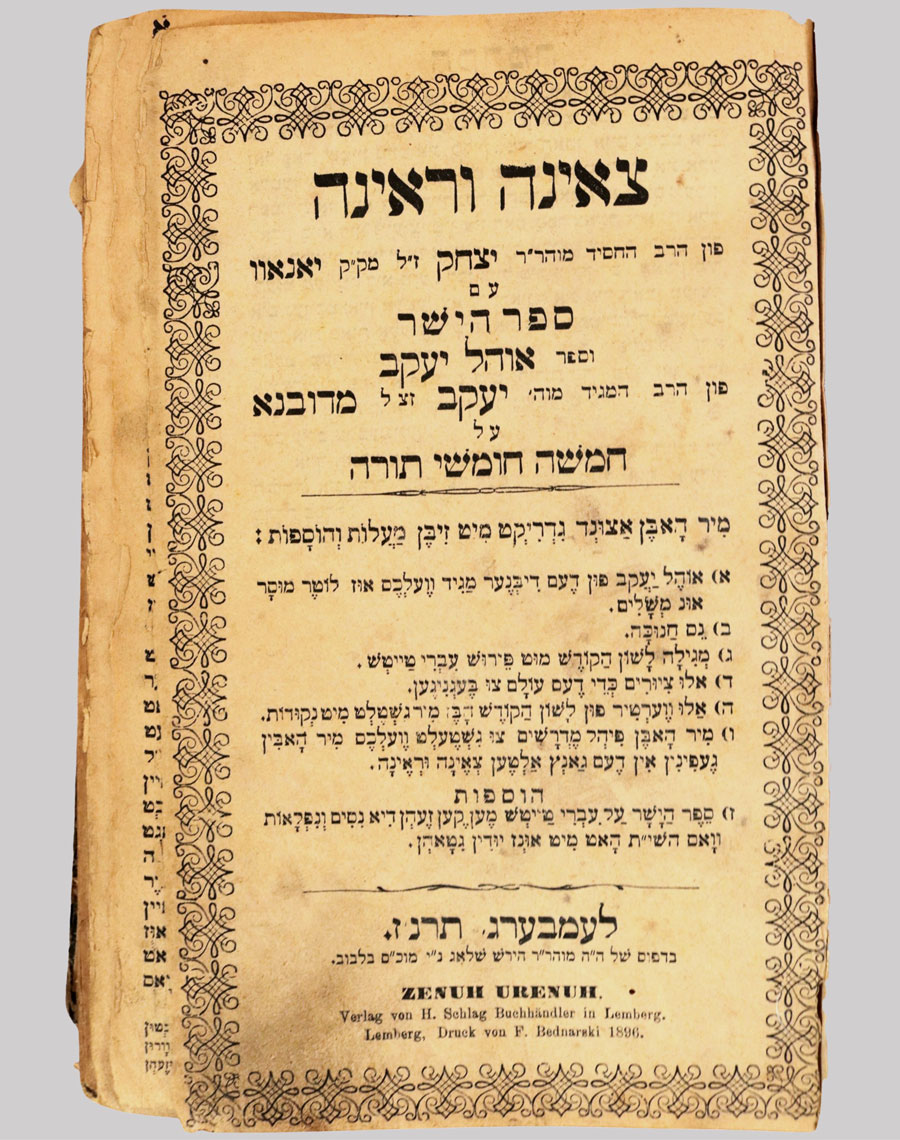

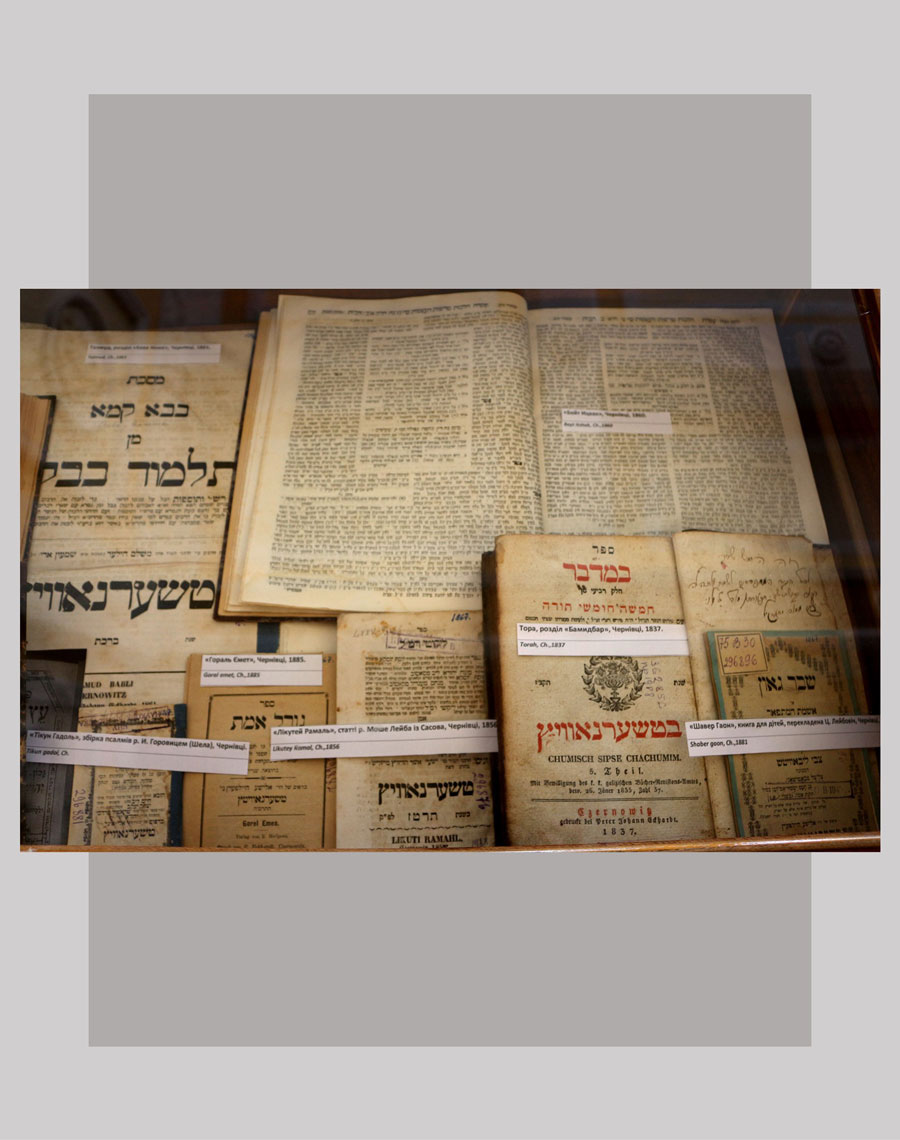

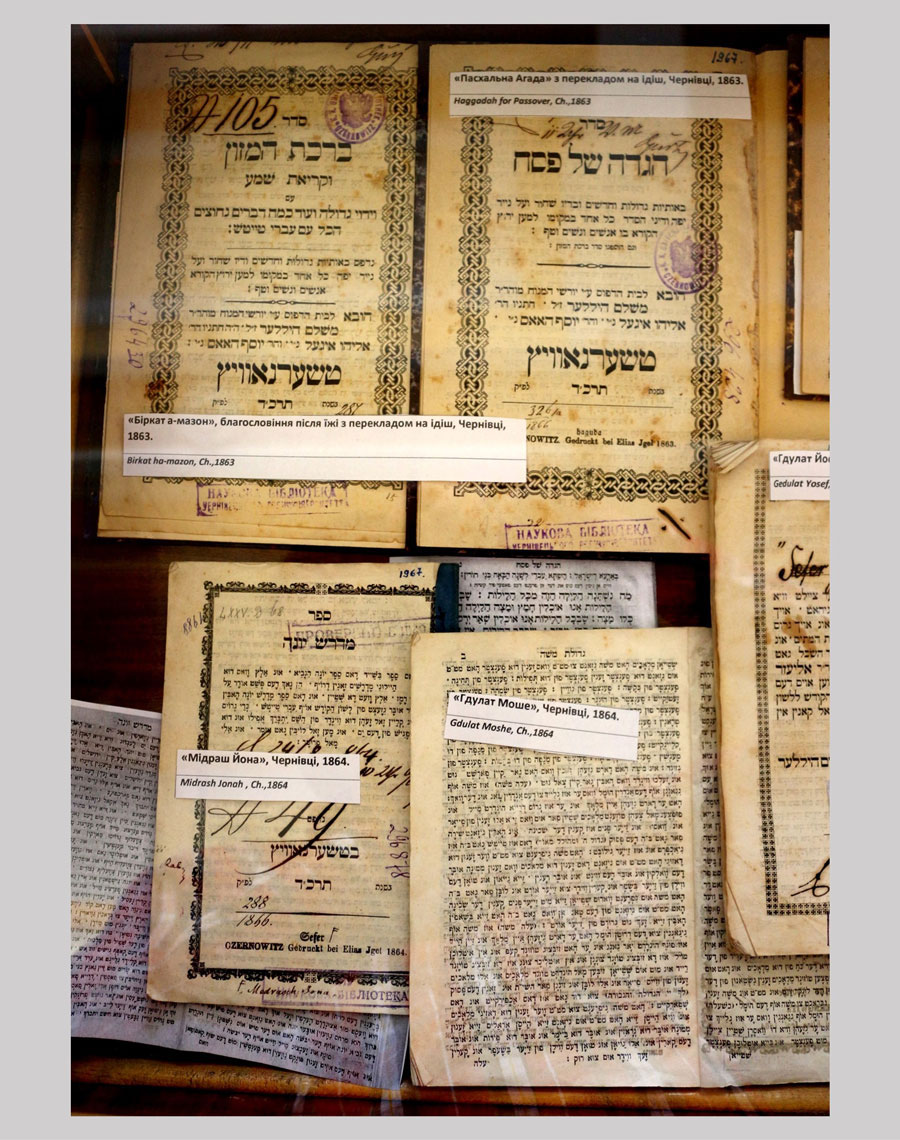

Hebrew/Yiddish printing

Lviv gained a reputation as a major center of Hebrew printing following a 1782 Habsburg governmental decree that required Hebrew presses to move to the city where a centralized censor's office had been established. Notably, two of the most prominent Hebrew printing houses in Lviv were directed by women. With the relaxation of censorship, Hebrew and Yiddish printing establishments proliferated, partly in response to the dramatic population growth that increased demand for prayer books and other religious texts. The growing strength of Hasidism also contributed to an increase in Hebrew and Yiddish publications, reflecting the polemics between the Hasidim and their opponents — both the Misnagdim (traditionalists) and Maskilim (modernists) — and the numerous compilations of hagiographic tales about Hasidic leaders and their teachings.

Read more...

Russian Jewish writers from tsarist Russia often printed their books in Lviv and Cracow in order to escape Russian censors. Lviv became not only a regional printing center but also an exporter to the Balkans. In 1863 alone, Lviv's Jewish printers (Madfes, Kugel-Levin, and Shtand) produced 112 Hebrew or Yiddish books, ranging from Hasidic and kabbalistic texts to works on Jewish history and Haskalah poetry. In Czernowitz (Chernivtsi), the non-Jewish firm of Johann Eckhardt brought in Jewish print specialists and began in 1835 to produce not only standard texts for routine religious uses but also esoteric texts and an ambitious line of biblical commentaries. Active Hebrew printing press also functioned in Transcarpathia — in Uzhhorod (1864) and Mukachevo (1871), where mostly rabbinic texts were produced.

sources

- Kenneth B. Moss, "Printing and Publishing: Printing and Publishing after 1800," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010),

- Israel Bartal, The Jews of Eastern Europe, 1772–1881 (Philadelphia, 2006), 42, 126.

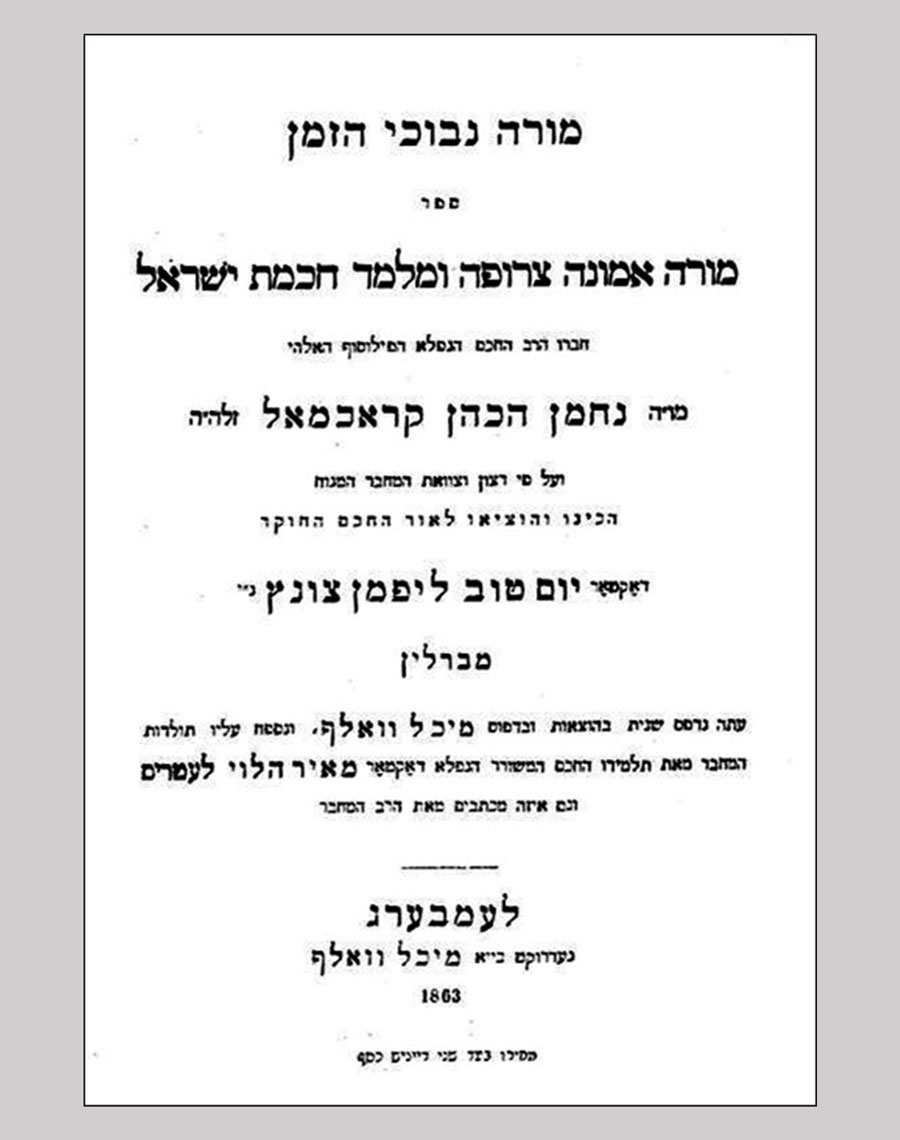

1851

The influential work, More Nevukhei ha-Zman ("Guide for the Perplexed of Our Time") by Nachman Krochmal was published in Lviv. In this book, Krochmal — a philosopher, theologian, historian, and one of the principal exponents of the Haskalah in Galicia — attempted to combine the Hegelian idealist conception of history with a modernized version of the Jewish historical mission. Krochmal had a significant influence on almost all those associated with the Haskalah in Eastern Europe.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. I, 259.

1861

The Ruthenian Club (Ruska Besida) was established in Lviv by young populists as a cultural-educational society to spread Ukrainian culture among the rural peasant population. Three years later, the Ruthenian Club established the first Ukrainian theatre anywhere and propagated the vernacular through plays staged in Lviv and the surrounding countryside. The Ruska Besida branched out to Chernivtsi in 1869.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 473;

- "Ruska Besida in Bukovyna," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1993).

1865–1907

Jewish children increasingly attended German public schools in Bukovina. In 1865, Jewish students represented 100 out of 162 students; in 1905, the figure was 664 out of 970. The proportion of Jewish students enrolled at the German-language university of Chernivtsi increased from 25 percent in 1883 to 42 percent in 1904.

sources

- Andrei Corbea-Hoisie, "Bucovina," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

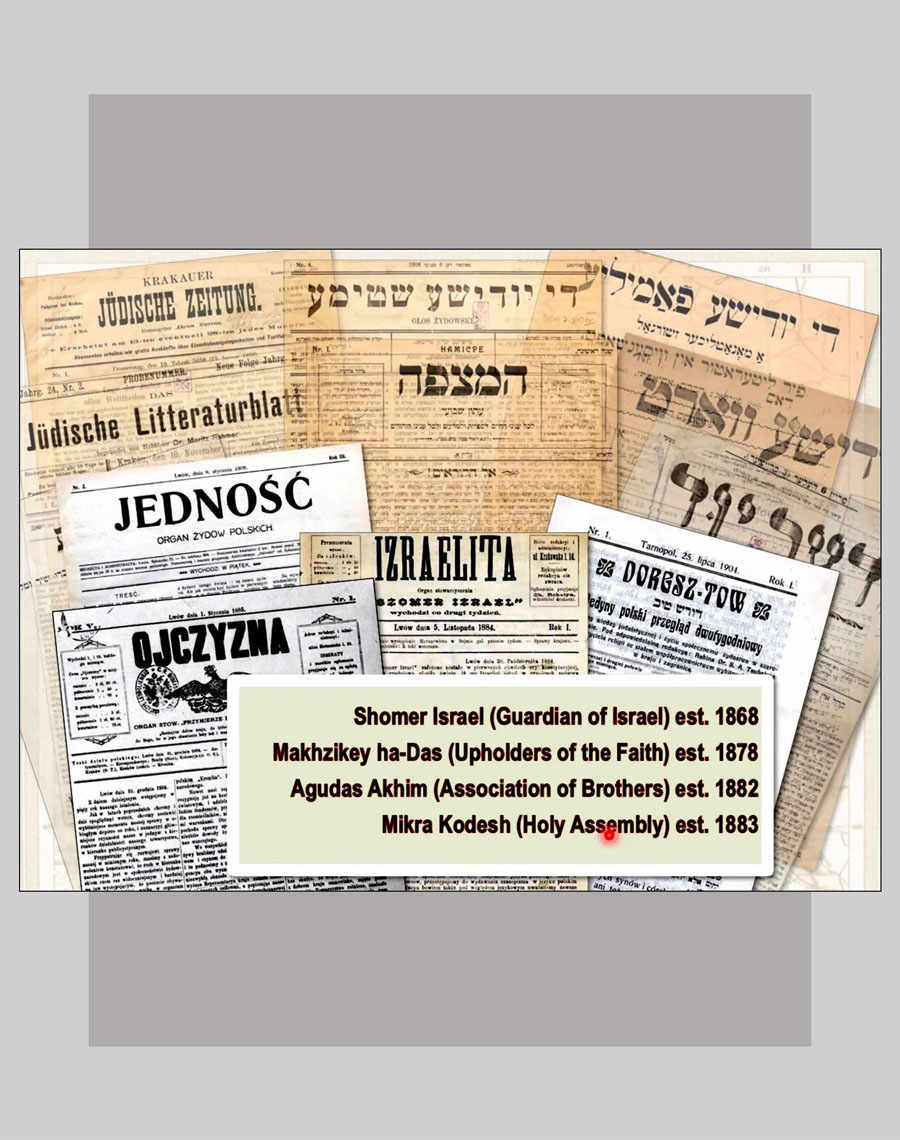

1868–1883

Ideological and political orientations among Jews in Galicia

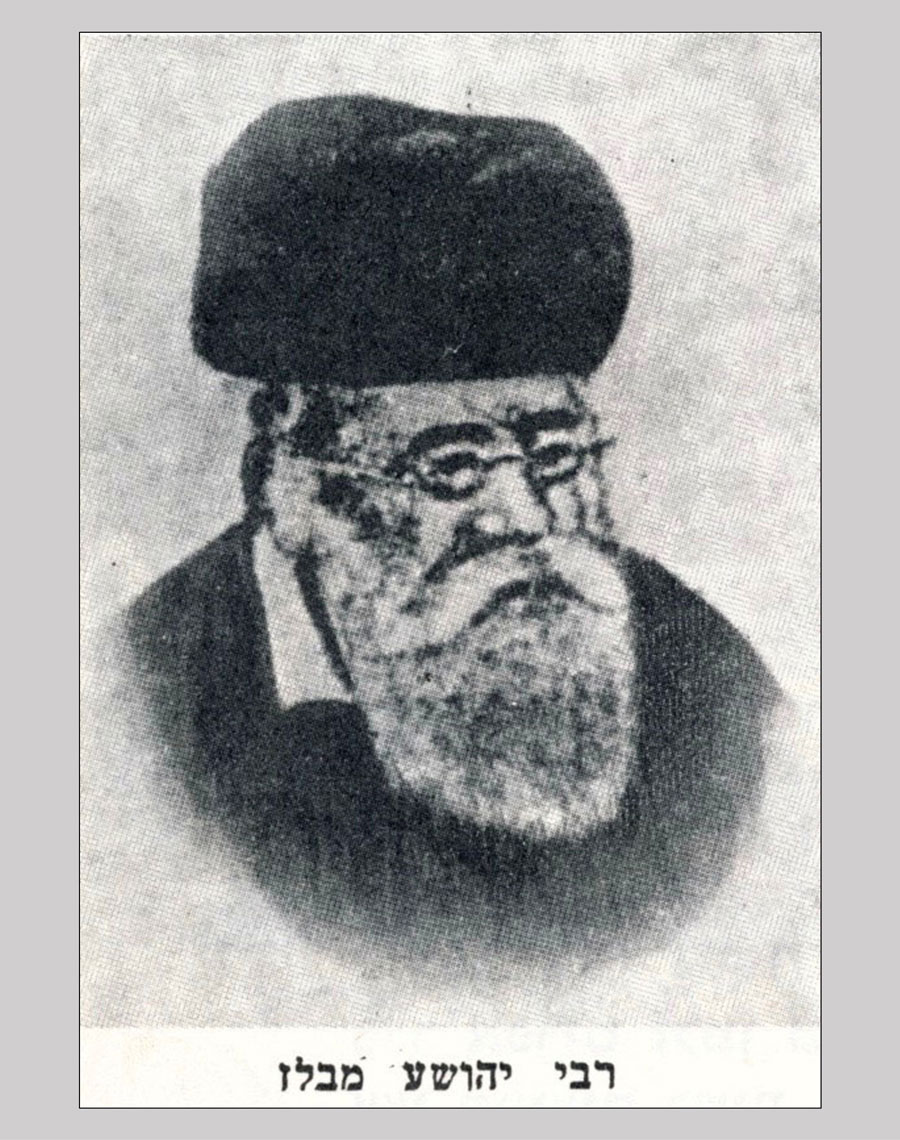

A variety of groups with conflicting cultural (and political) orientations emerged within Galician Jewry during this period — pro-Austrian assimilationist, pro-Polish assimilationist, Orthodox traditionalist, and Jewish nationalist. The first group, Shomer Yisrael, was founded in 1868 by liberal Jewish modernist professionals (physicians, lawyers, graduates of universities in Galicia or Vienna) who advocated the integration of Jews into Austrian-German society and culture. A different cultural scene emerged after a decade of de facto autonomy for Galicia under Polish domination and the active dissemination of the Polish language and culture through Galicia's educational system. In 1882, Jewish graduates of Polish schools and gymnasia, imbued with Polish patriotism, established an association Agudas Akhim (Przymierze Braci, Alliance of Brothers) to promote the assimilation of the Jews into Polish society, reaching out especially to youth. In contrast, in 1883, the Mikra Kodesh (Holy Convocation) Society was formed, with a Jewish nationalist orientation, attracting students from Polonized backgrounds who felt an increasing sense of rejection by antisemitic Polish nationalists.

Read more...

For its part, the large Jewish Orthodox sector had viewed all the modernizing trends with alarm for some time. In 1878 Shomer Yisrael appeared to be gaining increasing political influence and advancing its objectives to spread secular education among Galicia's Jews. In response, the Chief Rabbi of Cracow Shimon Sofer and the rebbe (spiritual leader) of the Belzer Hasidim, Yehoshua Rokeach, founded a political party, Mahzikei Hadas (Upholders of the Faith) to counter the threat they judged the assimilationists posed for traditional Judaism. Mahzikei Hadas, which by 1883 had some 40,000 registered members with branches across Galicia, tried unsuccessfully to obtain government approval for a statute that would require Jewish communities to be governed in accordance with Jewish religious law. Their proposal to split Jewish communities along ideological lines (as was the case in Germany and Hungary) was also rejected. Also unsuccessful was their effort to ensure the election of Orthodox representatives to communal and governmental institutions.

sources and related

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. I, 119–121;

- Rachel Manekin, "Galicia," "Shomer Yisra'el," "Agudas Akhim," "Makhzikey ha-Das," and Joshua Shanes, "Mikra Kodesh," entries in YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

Related

Chapter 5.1 1879–1880

1860s–1914

Ukrainian language and enlightenment

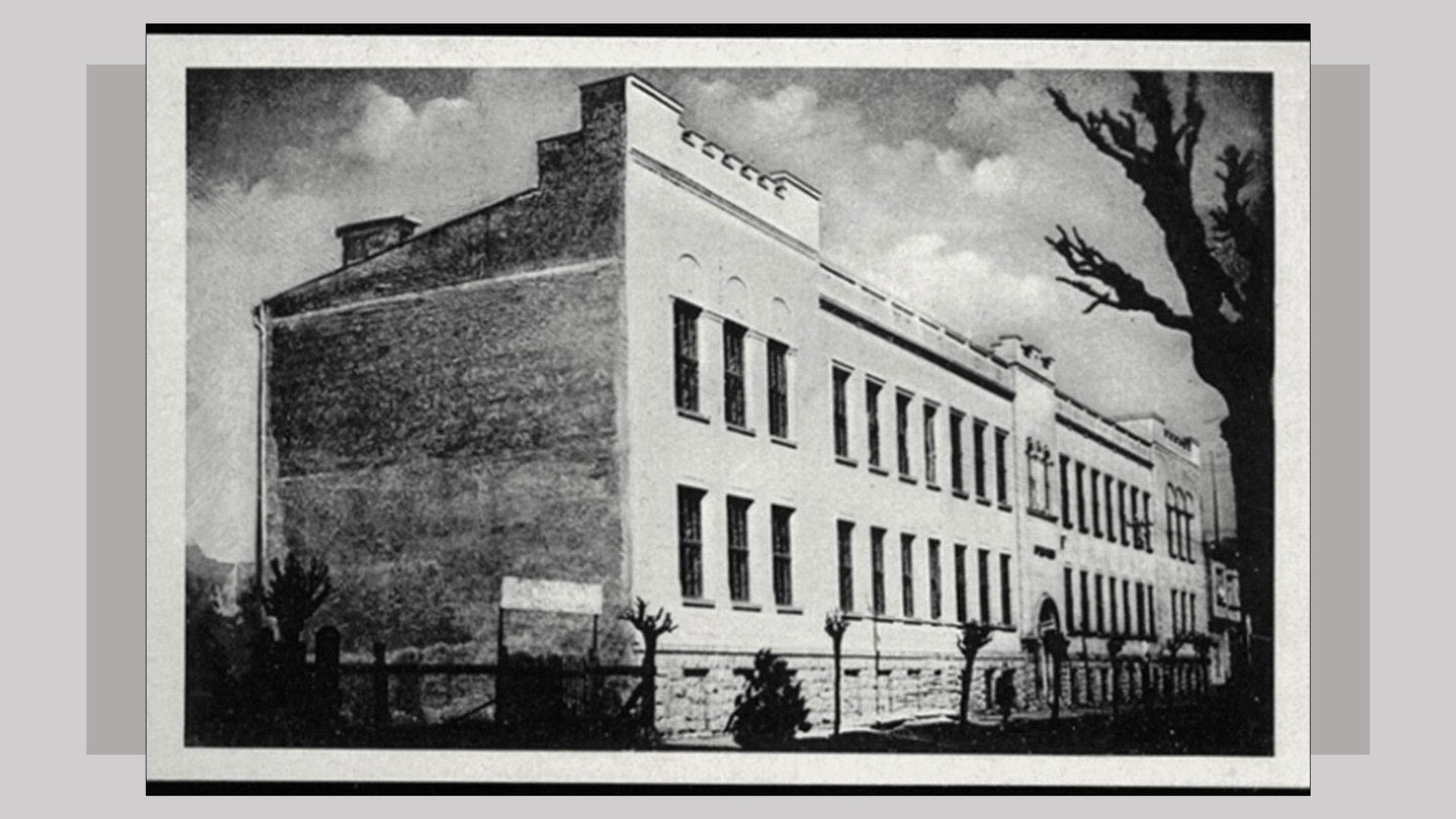

The Prosvita (Enlightenment) Society was founded in Lviv by a group of young populist intellectuals whose primary goal was to promote culture and education among the Ukrainian masses. It offered adult education classes, established village reading rooms and choirs, published textbooks and works in Ukrainian literature and history. In the 1890s, Prosvita also entered the economic sphere with a range of enterprises. By 1906, besides its headquarters in Lviv, it had a vast network throughout eastern Galicia, including 39 affiliates and branches, 1,700 reading rooms, and 10,000 members. By 1914, it had published 82 titles, which totalled 655,000 copies, all in vernacular Ukrainian. The Prosvita society was to become the most influential Ukrainian mass organization in Galicia and beyond.

Read more...

From the 1860s, the Habsburg authorities increasingly approved the use of the Ukrainian language in all spheres of public life, including in local administrative offices and the courts. By 1914 Ukrainian was the language of instruction in 2,500 elementary schools, sixteen secondary schools (gymnasia), ten teachers’ colleges, and ten departments at the University of Lviv.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 473;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Ukraine: An Illustrated History (Toronto, Second Edition, 2007), 183.

1864–1914

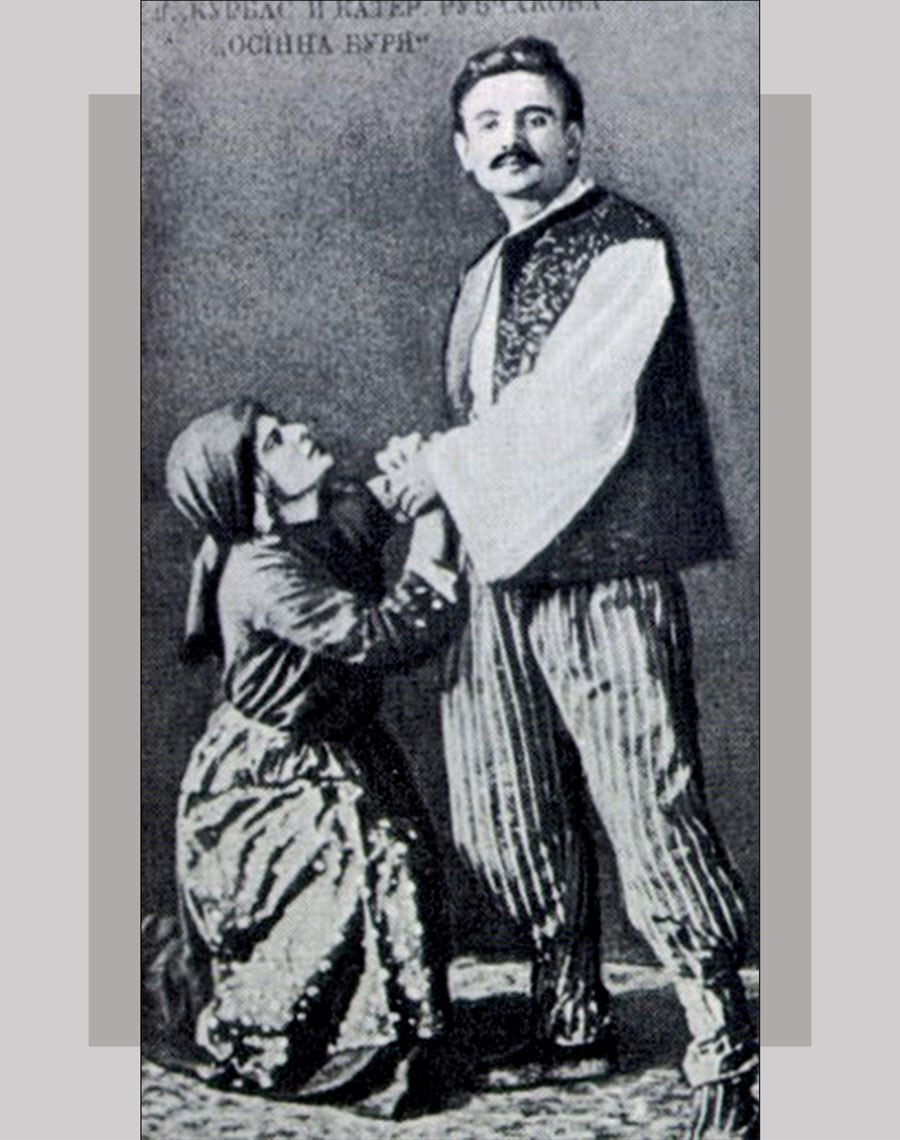

Ukrainian theatre in Galicia

Theatre contributed considerably to the awakening of national consciousness among Ukrainians. In an important landmark in the evolution of modern Ukrainian theatre, the Ruska (later Ukrainska) Besida Theatre, the first professional Ukrainian touring theatre in Austrian-ruled Galicia, was created in Lviv in 1864 and functioned for fifty years. Subsidized by the Ruska Besida Society in Lviv and occasionally supported by the Galician Diet, it served Galicia and Bukovina and also toured Poland and the Russian Empire. Its performances were mainly in the populist realist style.

Read more...

In its first years, it staged works from the Ukrainian classical repertoire (including Ivan Kotliarevsky and Taras Shevchenko) and works by contemporary Galician dramatists. During the 1870s–1880s, the theatre introduced local historical dramas and plays. In the 1890s, it staged Ivan Franko's realistic dramas, and after 1911, performances of Volodymyr Vynnychenko's psychological plays, Ukrainian operas, and many works in translation, including Western European and Russian plays and popular European operettas.

sources

- Valeriian Revutsky, "Theater," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1993).

1870s–1880s

Jewish performers in Galicia

The Broder Zingers, a group of itinerant Jewish singers from Brody, Galicia, pioneered a new entertainment genre — the revue show, which consisted of short sketches, songs, and dances staged at inns, restaurants, cafes, and beer gardens. The performers included former or current badhonim (traditional wedding entertainers) and singers in a cantor's choir. Their songs and performance style influenced Avrom Goldfaden, "the father of the Yiddish theatre," and his productions in Ukraine, Moldavia/Romania, and later in the United States. Among the first and most famous Broder Zingers was Berl Margulies, known as Berl Broder (ca. 1817–1886). The significance of Brody was that it was a stopping point on the travels of Jewish merchants to and from the Leipzig fair. Later the term 'Broder Singer' was applied to performers who had no connection with Brody but had adopted the genre.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. II, 389;

- Robert A. Rothstein, "Songs and Songwriters," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1870s

Education of Jewish and Ukrainian girls

After the introduction of compulsory secular education in Galicia, a custom developed among traditional Orthodox Jews to send their daughters to the government public schools. At the same time, they tried to protect their sons from the dangers of secularization by having them attend heders and yeshivas. In a parallel development, favouring girls for a state education was also the practice of the Ukrainian peasantry, who wanted their sons to work in the fields from an early age

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. II, 123;

- Gardetska, O. Trofymovska, "Education of Women," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1984).

1873–1898

The Shevchenko Scientific Society

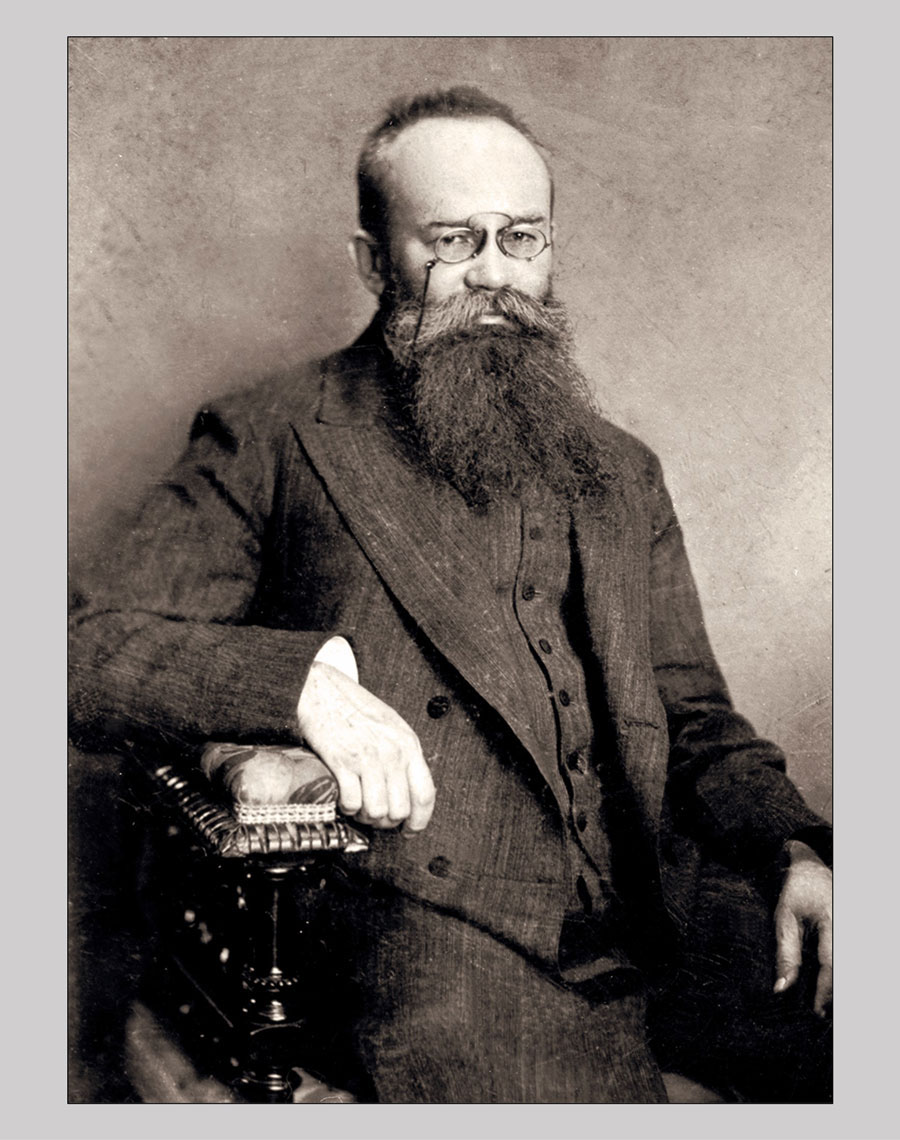

The Shevchenko Society was established in Lviv in 1873 by populist Ukrainophiles from Dnieper Ukraine to promote Ukrainian literature and literary scholarship. As Ukrainian scholarship was hampered in the following years by tsarist government restrictions, the initial literary orientation of the society was broadened in 1892 to include history and other academic disciplines, as reflected in its name change to the Shevchenko Scientific Society (NTSh). Under the dynamic presidency (1897–1913) of the eminent Ukrainian historian and political figure Mykhailo Hrushevsky (who had emigrated from the Russian Empire in 1894 to take up a professorship at the University of Lviv), the NTSh acquired pan-Ukrainian importance and academic prestige. Hrushevsky also served as director of the Historical-Philosophical Section, assisted by Volodymyr Hnatiuk as secretary (1898–1926), and headed the Society's Ethnographic Commission. With Hrushevsky's prominent role in the NTSh and Ivan Franko serving as director (1898–1908) of the Philological Section, the NTSh became a de-facto academy of sciences to which virtually all Ukrainian scholars belonged. The involvement of younger scholars gave the NTSh a quasi-university function. The participation of NTSh members in international congresses and conferences and the exchange of publications with nearly 250 foreign institutions established the Society's international reputation.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 473–474;

- Bohdan Kravtsiv, Volodymyr Kubijovyč, "Shevchenko Scientific Society," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1993).

1885–1890

Depiction of Jews in Ukrainian literature

Natalia Kobrynska published a number of short stories that include depictions of Jews and Jewish life in Western Ukraine. Kobrynska's short stories deal with women's and social issues in a populist-realist style, showing modernist interest in individual psychology and folk beliefs. Born in the vicinity of Sniatyn and resident of Bolekhiv, Western Ukrainian towns with a high proportion of Jewish inhabitants, she learned Yiddish (in addition to German, French, Polish, and Russian) and became familiar with Jewish community life. Her familiarity with real Jews and interest in individual behaviour may explain why the Jewish characters in her stories are not stereotyped stock characters but rather individuals depicted as such. This perspective is evident in her portrayal of the diverse Jews who make up most of the crowd at a train station. These include a helpful Jewish woman who advises the main character on how to obtain a train ticket; a variety of Jews actively campaigning for their favoured political candidates; the Jewish wagon drivers; and a Jewish girl whose abject poverty leads to a fixation with thriftiness and self-denial.

sources

- Myroslav Shkandrij, Jews in Ukrainian Literature. Representation and Identity (New Haven, 2009), 68–69;

- Danylo Husar Struk, "Kobrynska, Nataliia," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1989).

1886

The Galicia-born poet Naftali Herz Imber, an unconventional vagabond figure, published his first book of poems,Barkai ("Morning Star"), in Jerusalem, at a time when he held a position as secretary to the eccentric Christian Zionist, Sir Laurence Oliphant. The book included a nine-verse poem called Tikvateinu ("Our Hope"), an adaptation of a purported earlier version written in 1878 when Imber was living in Iași Romania and was inspired by the Hovevei Zion pioneers who founded the village of Petah Tikvah in the Land of Israel. In 1886 the Chovevei Zion (Lovers of Zion) adopted the poem as their anthem. Later the new State of Israel adopted Imber's lyrics, with some changes, for the official national anthem, renaming it Hatikvah ("the Hope"). Imber eventually moved to the United States, where he died, ravaged by alcohol and impoverished — described by the prominent Yiddish journalist Abraham Cahan as a misunderstood tragic figure with a poetic soul. In 1953 Imber's remains were reburied in Jerusalem. The source of the melody for Hatikvah is disputed but widely attributed to Shmuel Cohen, a Moldavian-born resident of Rishon le-Zion, the second Jewish farm settlement established in Ottoman Palestine in 1882. In 1888, Cohen composed a melody for Imber's poem, based on a Romanian folk song "Cart with Oxen" — a melody itself inspired by "Die Moldau" by the Czech composer Bedřich Smetana.

sources

- Cecil Bloom, "Hatikvah - Imber, his poem and a national anthem," Jewish Historical Studies (Jewish Historical Society of England), Vol. 32 (1990-1992), 317–336.

1898–1937

Mykhailo Hrushevsky's “Istoriia”

The first volume of Mykhailo Hrushevsky's monumental Istoriia Ukraïny-Rusy (History of Ukraine-Rus') was published in Lviv in 1898, initiating the first major synthesis of Ukrainian history. By the time World War I broke, Hrushevsky was working on volume eight, at the same time as his political activities intensified. Thetenth and last volume of Hrushevsky's Istoriia, published posthumously in 1937, brought the project only up to the 1650s. This multi-volume work is still regarded as the most comprehensive account of the ancient, medieval, and early modern history of the Ukrainian people.

Read more...

The very title of Hrushevsky's Istoriia Ukraïny-Rusy was a programmatic statement regarding the continuity between Kyivan Rus′ and modern Ukraine. It challenged the Russians' monopoly on the name Rus' and asserted that the history and culture of the Ukrainian nation are unique and distinct from the Russian. Because of his emphasis on the lives of simple people rather than rulers and elites, Hrushevsky's approach has been described as belonging to the populist school of Ukrainian historiography. However, later in his career, the interests of state and nation also became prominent in his work.

While working on the Istoriia, Hrushevsky also produced popular single-volume histories of Ukraine and numerous influential articles. He was also a belletrist, author of tales, dramas, and short stories, and contributor to the history of Ukrainian literature and other facets of Ukrainian culture. Hrushevsky is credited with developing Ukrainian scholarly and cultural life in Lviv in the mid-1890s. After moving to Kyiv, he played an increasingly active political role in Russian-ruled Ukraine, leading to his election in 1918 as president of the Ukrainian National Republic (UNR). Hrushevsky returned to Soviet Ukraine in the 1920s and, in the context of Ukrainianization, worked at Kyiv University and was elected to the Academy of Sciences.

The Istoriia was internationally acclaimed at the time of its publication. However, in Soviet Ukraine after the 1930s, no scholarly references to it were permitted to appear, and later Soviet publications dismissed Hrushevsky as a "nationalist historian." Attempts in the 1960s to "rehabilitate" him and his works failed; it was only in the late 1980s that the Ukrainian public began to regain access to his magnum opus.

sources

- Frank E. Sysyn, "Mykhailo Hrushevsky and the History of Ukraine-Rus'," "Who was Mykhailo Hrushevsky?" and CIUS Press. On Hrushevsky in Soviet Ukraine, see the Ukrainian-language volumes by Iurii Shapoval.

1880s–1900s

Polonization of Galicia's Jews

While the majority of Galicia's Jewish population did not assimilate to any of the surrounding cultures, the active promotion of Polish-language secular education led to the emergence of a Polonized Jewish intelligentsia, including doctors, lawyers, and other professionals. Galician schools, run by a Council of Education dominated by Poles, were a powerful instrument in spreading the Polish language and culture in the province. It was only in 1890 that a Ukrainian was appointed, and in 1906 that a Jew sat on the Council. During the Austrian census of 1900, only 5 percent of Galician Jews gave Ukrainian as their language of daily usage, while 77 percent gave Polish and 17 percent German. (Yiddish was not considered a language in the Austrian census.)

sources

- John-Paul Himka, "Ukrainian-Jewish Antagonism in the Galician Countryside During the Late Nineteenth Century," in Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective, Peter Potichnyj & Howard Aster, eds. (Edmonton, 1988), 142;

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. II, 122–124.

1900–1913

Andrei Sheptytsky's contribution to culture in Galicia

Andrei Sheptytsky, a towering figure in both physical stature and sociocultural influence, was appointed Archbishop of Lviv and Metropolitan of Galicia, a position he held until his death in 1944. Born into a Polonized Ukrainian family, Sheptytsky rediscovered his Ukrainian roots and came to identify with the Ukrainian national cause. Because of his aristocratic status, wealth, and personal attributes, he was welcomed among both the Polish and Austrian elites and was influential in shaping developments in the religious and cultural spheres, including in education and the arts. He was particularly well-suited to furthering the cause of education and scholarship, including among the clergy, as he held three doctoral degrees (law, theology, and philosophy) and studied about a dozen foreign languages. He supported several monastic orders — especially the Studite order, which he helped restore (1904) — and their educational institutions, orphanages, and vocational and trade schools.

Read more...

Among his philanthropic projects was the establishment of the Ukrainian National Museum, beginning in 1905, to which he donated his private collections of folk and religious artifacts (some 10,000 items). Beyond serving as a storehouse for Ukrainian art, the Museum (which opened in 1913) advanced Sheptytsky's vision of the role it could play in countering ignorance about Ukraine's historical and cultural past.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 476;

- Ann Slusarczuk Sirka, "Sheptyts'kyi in Education and Philanthropy," and Myroslava M. Mudrak, "Sheptyts'kyi as Patron of the Arts," in Paul Robert Magocsi, editor, Morality and Reality: The Life and Times of Andrei Sheptyts'kyi (Edmonton, 1989), 271–272, 289–293.

1903–1906

Modernist Jewish art in Galicia

An etching by the Drohobych-born art nouveau illustrator and printmaker Ephraim Moses Lilien (1874–1925) has been described as perhaps the most vivid and best-known merger between Jewish martyrology and Christian iconography. The frequently reproduced 1903 etching bears the caption: Le-Metim 'al kiddush ha-shem be-Kishinov (Dedicated to the Martyrs of Kishinev). Lilien later joined the Lithuanian Jewish artist and sculptor Boris Schatz in establishing the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem, where a modern style of Jewish art was encouraged in painting, sculpture, and design. Lilien taught the Bezalel Academy's first class in 1906.

sources

- Olga Litvak, "Painting and Sculpture,"YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1905

Karl Emil Franzos published his novel Der Pojaz (The Clown), which encapsulates his views and aspirations for freeing Galicia — its Jewish inhabitants in particular — from religious obscurantism, backwardness and corrupt bureaucracy. At the centre of the novel is a young Jewish man who seeks, through a career in the theatre, to escape his confining circumstances and the rigid attitudes and religious practices of the Orthodox Jewish society. Though completed in 1893, the novel was published posthumously, possibly because Franzos lost faith in cultural assimilation as the way forward for Jews, as he witnessed rising antisemitism in the 1890s. Indeed, his critics have claimed that his depictions of East European Jewish life had the effect of reinforcing existing negative preconceptions. Much of his writing focused on relations between the different national groups in the region — Poles, Ukrainians, Russians, Germans and Jews — with empathy for the oppressed groups, the Ukrainian peasants and shtetl Jews in particular.

sources

- Ritchie Robertson, The 'Jewish Question' in German Literature, 1749–1939: Emancipation and its Discontents (Oxford, 2001), 413, 417–420.

1905

Ukrainian writers

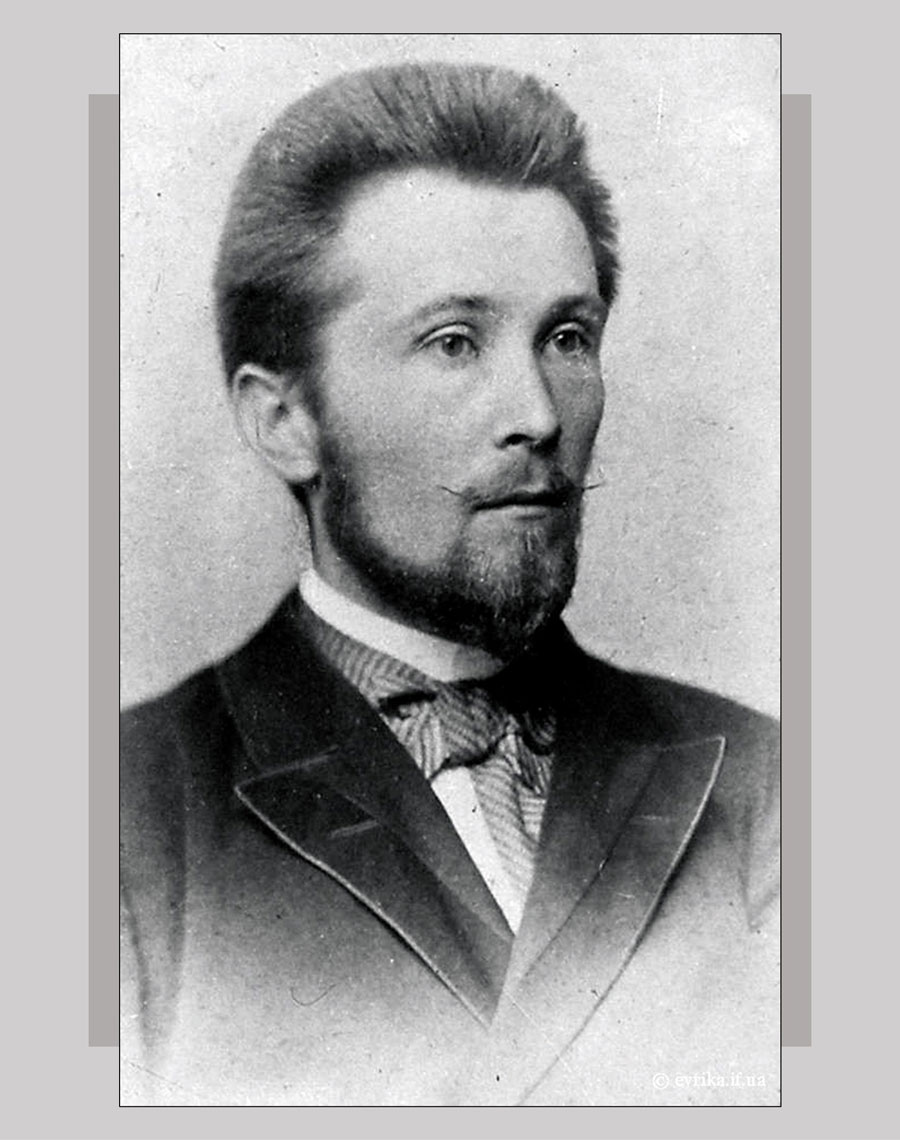

The publication of Ivan Franko's narrative poem Moisei (Moses) illustrates a growing trend among turn-of-the-century Ukrainian writers to draw inspiration for the Ukrainian national awakening from the Hebrew Bible. The poem is noteworthy for its masterful alignment of images of ancient Israel and contemporary Ukraine as subjugated nations and its declared admiration for a people struggling to assert its identity in the face of overwhelming hostility.

Read more...

As a prolific writer in a variety of genres (including drama, poetry, literary prose, linguistics, ethnography, history, and essays), Franko gained prominence as a central figure in Ukrainian political, civic, and cultural life. Franko also knew and wrote more on Jewish topics than any other Ukrainian author. He had studied Hebrew influences in Old Rus' literature and Ukrainian folklore and often included biblical motifs in his poetry. He also had a good command of the Yiddish language and familiarity with Galician Jewish life since childhood.

sources

- Ivan Rudnytsky, "Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Nineteenth-Century Ukrainian Political Thought," in Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective, Peter Potichnyj & Howard Aster, eds. (Edmonton, 1988), 78–79;

- Myroslav Shkandrij, Jews in Ukrainian Literature. Representation and Identity (New Haven, 2009), 55–56;

- Yaroslav Hrytsak, "A Strange Case of Antisemitism," in Omer Bartov and Eric D. Weitz, Shatterzone of Empires (Bloomington, Indiana, 2013), 228, 231.

1908

Yiddish writers

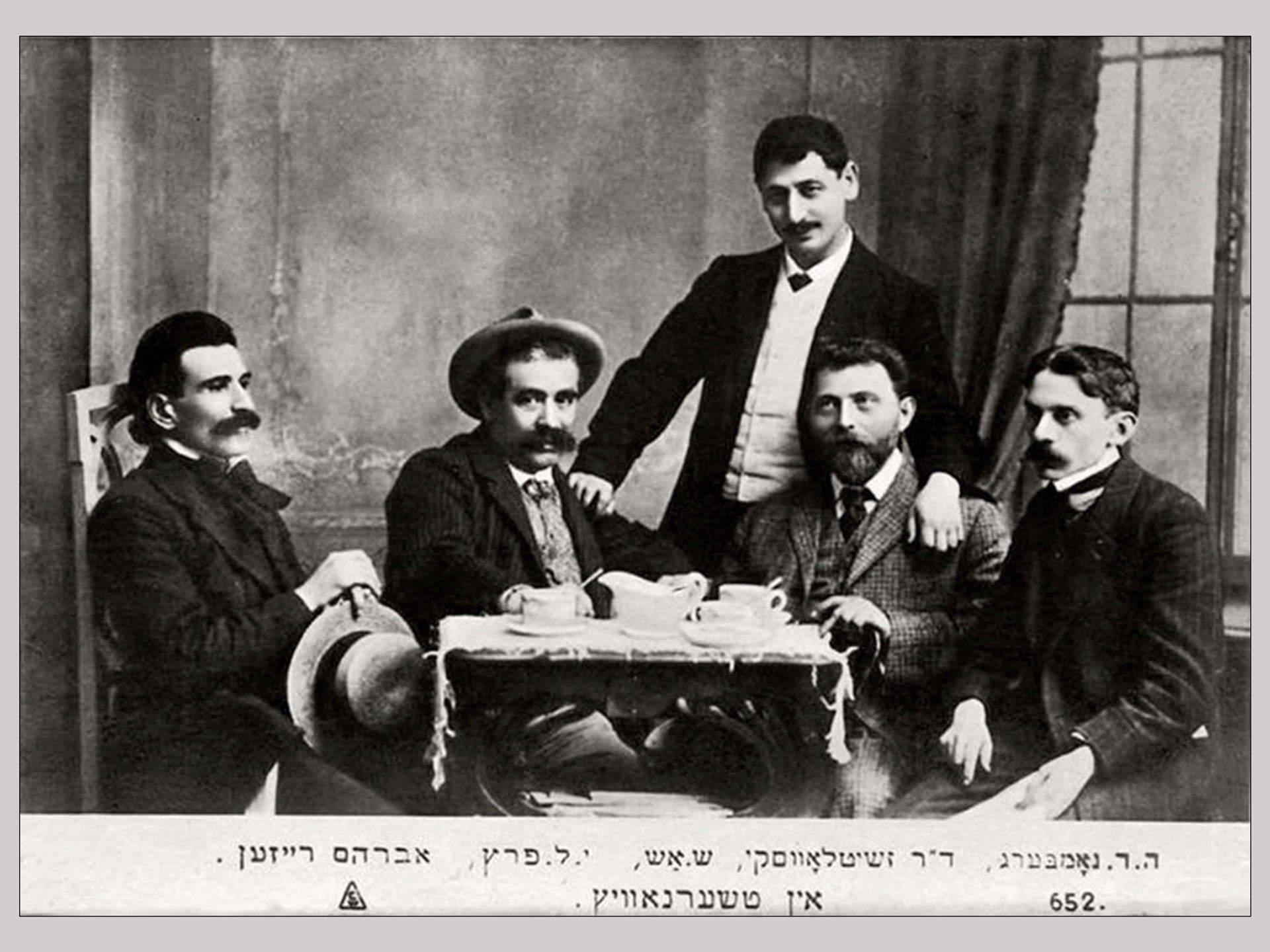

The first international conference on the Yiddish language and its role in Jewish life was convened in Czernowitz (Chernivtsi), then capital of the Austrian imperial province of Bukovina. The conference was the brainchild of Nathan Birnbaum (1864–1937), a Jewish educator, essayist, philosopher, politician, and social organizer. Leading Yiddish writers, such as Y.L. Peretz, and Sholem Asch, participated in the conference. Issues addressed include the need for Yiddish schools and teachers; support for the Yiddish press, theatre, and literature; and addressing the declining use of Yiddish by young people. A passionate debate focused on the status of Yiddish — whether Yiddish was "the" national language or only "a" national language of the Jewish people. Notwithstanding fierce opposition from those promoting the Hebrew language, the conference set in motion a process whereby Yiddish was eventually codified as a distinct literary language rather than a 'jargon.'

sources

- Joshua A. Fishman, "Czernowitz Conference," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010);

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 465.

1868–1900s

Magyarization of Ukrainians and Jews in Transcarpathia

The Hungarian authorities' assimilationist Magyarization policy in Transcarpathia, following the creation of the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary in 1868, undermined both Ukrainian and Jewish cultural life. It led to the suppression of institutionalized Ukrainian education, a decline in publications in the Cyrillic alphabet, and significant assimilation of both the Ukrainian and Jewish intelligentsia.

Read more...

By 1909, 90 percent of the Ukrainian (Ruthenian) schools in Transcarpathia were closed, and the remaining 10 percent had some kind of bilingual instruction. The population boycotted Hungarian-language schools, leading to extreme illiteracy among the Ukrainian peasants.

The majority of Jews in Transcarpathia had little or no secular schooling. According to one scholar, 30 percent of the Jews in Transcarpathia in 1900 were illiterate by Hungarian educational standards. They worked in agriculture and lived in the same poverty as their Ukrainian neighbours. Culturally, they were shaped primarily by Hasidism, dominated in this region by ultra-conservative, miracle-working rabbis.

Hungarian nationalist activists — in their attempt to increase the importance of the Hungarian language in a region where Ukrainians were the numerically dominant ethnic group — also promoted the establishment of secular Jewish schools in Transcarpathia, with Hungarian as the language of instruction. Such schools began to thrive in the 1870s, angering the ultra-Orthodox Jewish community.

As a result of the Magyarization policy, many members of the Ukrainian and Jewish intelligentsia, including middle-class professionals, assimilated into the Hungarian milieu. An indicator of the impact of Magyarization is that one-quarter of urban Jews in Transcarpathia did not register as being of Jewish nationality, only of the Jewish religion.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, The People from Nowhere: an illustrated history of Carpatho-Rusyns (Uzhorod, 2006), 61;

- Alexander Baran, "Jewish-Ukrainian Relations in Transcarpathia," in Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective, Peter Potichnyj & Howard Aster, eds. (Edmonton, 1988), 161, 163;

- Volodymyr Kubijovyč, Vasyl Markus, Ivan Lysiak Rudnytsky, Ihor Stebelsky, "Education," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1993);

- Yeshayahu A. Jelinek, The Carpathian Diaspora (New York, 2007), 94–96.

1909–1910

Boichukist Neo-Byzantine art

After establishing an art studio school in Paris, Mykhailo Boichuk and his students mounted a historic exhibition in 1910 at the Salon des Indépendants on the revival of Byzantine art. Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky enabled this achievement. As a serious collector of Ukrainian icons, Sheptytsky appreciated Boichuk's Neo-Byzantine style of painting. As observed by art historian Vita Susak: "it is doubtful if the School for the Revival of Byzantine Art…would have come to fruition without Sheptytsky's three-year-long sponsorship of Boichuk's stay in Paris." Following Boichuk's return from Paris, he restored numerous fifteenth- and sixteenth-century icons at the National Museum in Lviv.

Read more...

Vita Susak's analysis of the parallel development of "national styles" among early twentieth-century Ukrainian and Jewish artists highlights their similarities and mutual influences. Their respective modernist "national styles" "blended traditional folk motifs and local scenes with avant-garde ideas," giving rise to both the Ukrainian artistic school of Boichukism and the Jewish Kultur-Lige.

sources

- Vita Susak, "Parallels in Ukrainian and Jewish 'National Styles' in Art in the First Third of the Twentieth Century," in Wolf Moskovich and Alti Rodal, editors, The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter: Cultural Dimensions, Volume 25 of Jews and Slavs (Jerusalem: Hebrew University of Jerusalem, "Philobiblon" 2016) 116, 119.

1910

In Galicia, the vast majority of Jews (808,000 of 856,000) who gave their religion as Jewish identified Polish as their primary language; smaller numbers indicated German (26,000) or Ukrainian (22,000) as their primary language. While the vast majority of Galicia's Jews remained Hasidic traditionalists who eschewed contact with the non-Jewish world, the cultural elite favoured assimilation to either German or Polish culture, with the Polonophile tendency prevailing after the 1870s.

In 1910, 1,386 Jewish students enrolled at the University of Lviv (26 percent of the total student body), where the language of instruction was primarily Polish.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. II, 123, 139;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 449.