1720s–1790s

Until the 1720s, Jews were almost totally absent in the Russian Empire, except for occasional travellers and migrant merchants. Motivated by traditional Christian hostility, the Russian state continued to ban Jews from settling in its interior in the following decades. In the early 1740s, Empress Elizabeth overruled the senate's favourable response to petitions from authorities in Ukrainian regions of the empire, requesting that Jews be granted at least temporary residence and be allowed to attend the fairs, which were a vital element of Ukrainian economic life. Explaining her decision, Elizabeth stated: "I desire no profit from the enemies of Jesus Christ."

Read more...

At the start of her reign in 1762, Catherine II reaffirmed the ban on Jewish settlement, not wanting to antagonize public opinion. After 1778, Jews were classed as urban and as members of two estates — merchants and townspeople — leading to harassment by Christian counterparts resenting the Jewish competition. As merchants, Jews were also barred from the countryside, where they might 'enrich themselves' at the expense of the peasants.

A 1786 decree, reflecting Enlightenment principles, allowed for some exceptions to the residence restrictions in rural regions. This decree was especially significant in Ukraine, where many Jews settled in villages. Periodically, the exceptions were rescinded, and Jews were again banned from the countryside and forced to move to towns and cities. Jews (and some later historians) considered such measures as discriminatory and oppressive. Imperial policies regarding Jewish settlement evolved after the mid-1790s when Russia annexed Polish-Lithuanian territories containing the largest Jewish population in the world.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. I, 325–333;

- Michael Stanislawski, "Russia: Russian Empire," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1825–1855

Policies affecting Jews under Tsar Nicholas I (and his successors) were dominated by a strong belief that Jews had a harmful impact on the surrounding population and that Jewish "exploitation" was responsible for the miserable state of the peasantry. Tsar Nicholas I allowed Jews to live in Kyiv temporarily because of their usefulness in developing the city's commerce but then compelled them to leave in 1835. An exception was made for the few Jewish contractors tasked with building the fortress of Kyiv and the University of St. Volodymyr.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. II, 182.

1845

An imperial decree prohibited traditional Jewish dress that "distinguishes Jews from their neighbours so that they form a distinct caste and remain steeped in their prejudices despite the government's best efforts." The decree was at times enforced with gratuitous brutality, as suggested in a petition from the Jewish community of Zhytomyr: "On the streets, district inspectors tear the wigs off Jewish women's heads, bonnets, and other head attire; they pull them by their hair to the police station and pour a few buckets of cold water on them; they keep them under arrest for 48 hours, and then finally make them sweep the streets in public."

sources

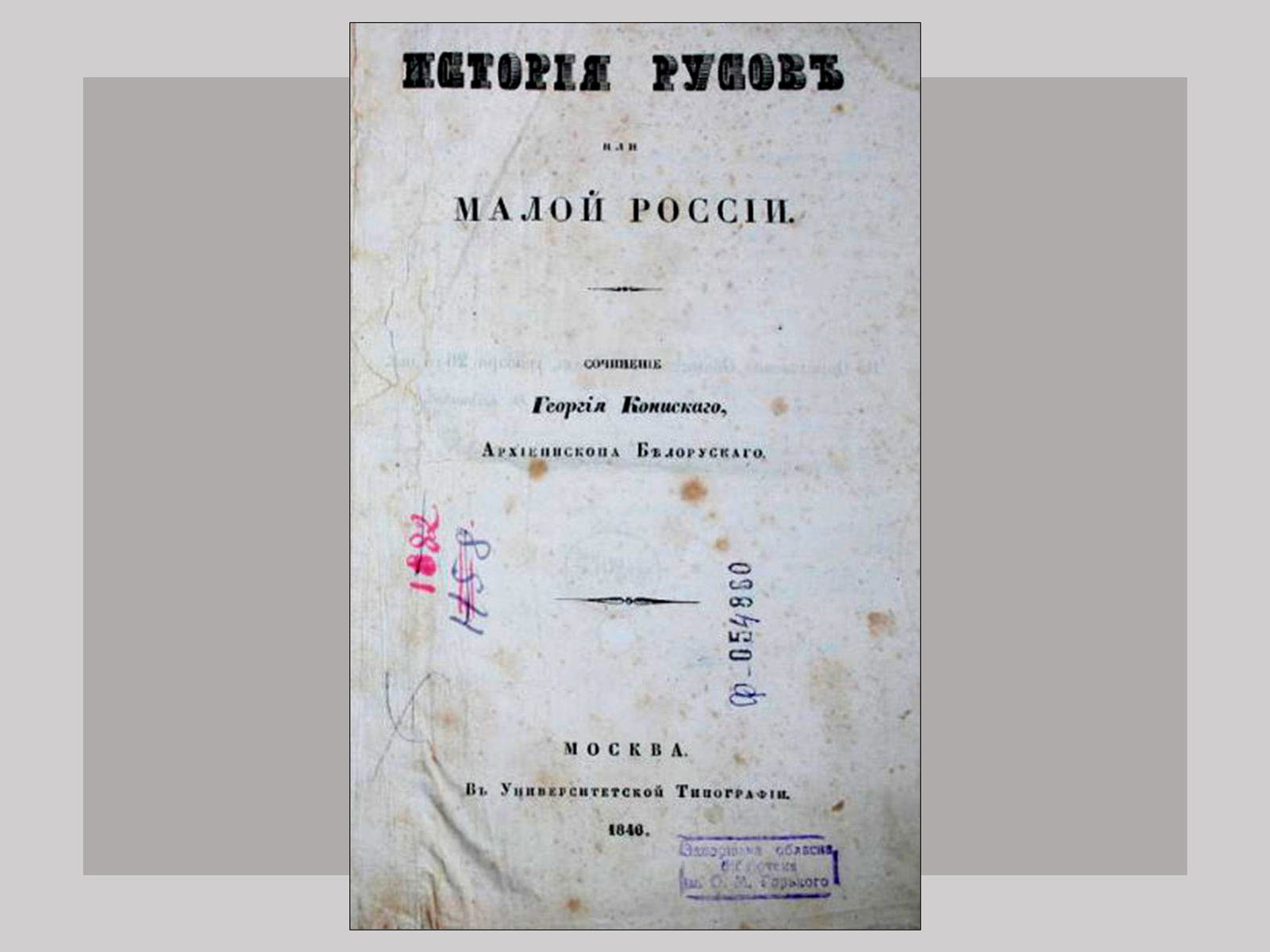

1846

A highly influential book, author anonymous, was published in Moscow — Istoriia Rusov ili Maloi Rossii (A History of the Rus' People or of Little Russia). This book idealizes the heroic struggles of the Ukrainian Cossacks while conveying anti-Polish and anti-Jewish motifs. One of its most resonant motifs, borrowed from Polish literature, depicts the stereotypical exploitative Jewish leaseholder who "holds the keys to the church" — who humiliates Orthodox Christians by demanding payment from them for attending church services. Historian Judith Kalik has found archival references to Catholic landowning magnates sealing Catholic churches due to unpaid debts, and also synagogues sealed for failure to pay interest on loans. These findings may be the grain of truth in a stereotype that took on a life of its own.

Read more...

Historian Serhii Plokhy describes the Istoriia (which circulated in manuscript for over two decades before it was published) as "by far the most important text in the formation of the Cossack myth and Ukrainian historical identity." Plokhy considers that the Istoriia is "neither a conscious manifesto of Russo-Ukrainian unity nor of rising Ukrainian nationalism — the two opposing interpretations advanced by modern scholarship — but rather an attempt on the part of the Cossack officer elite to negotiate the best possible conditions for their incorporation into the [Russian] empire." Plokhy also notes that the Istoriia treats Jews for the first time in Ukrainian tradition as an ethnic or racial category rather than a religious one, promoting the view that Jews cannot escape their Jewish essence and character by converting to Christianity.

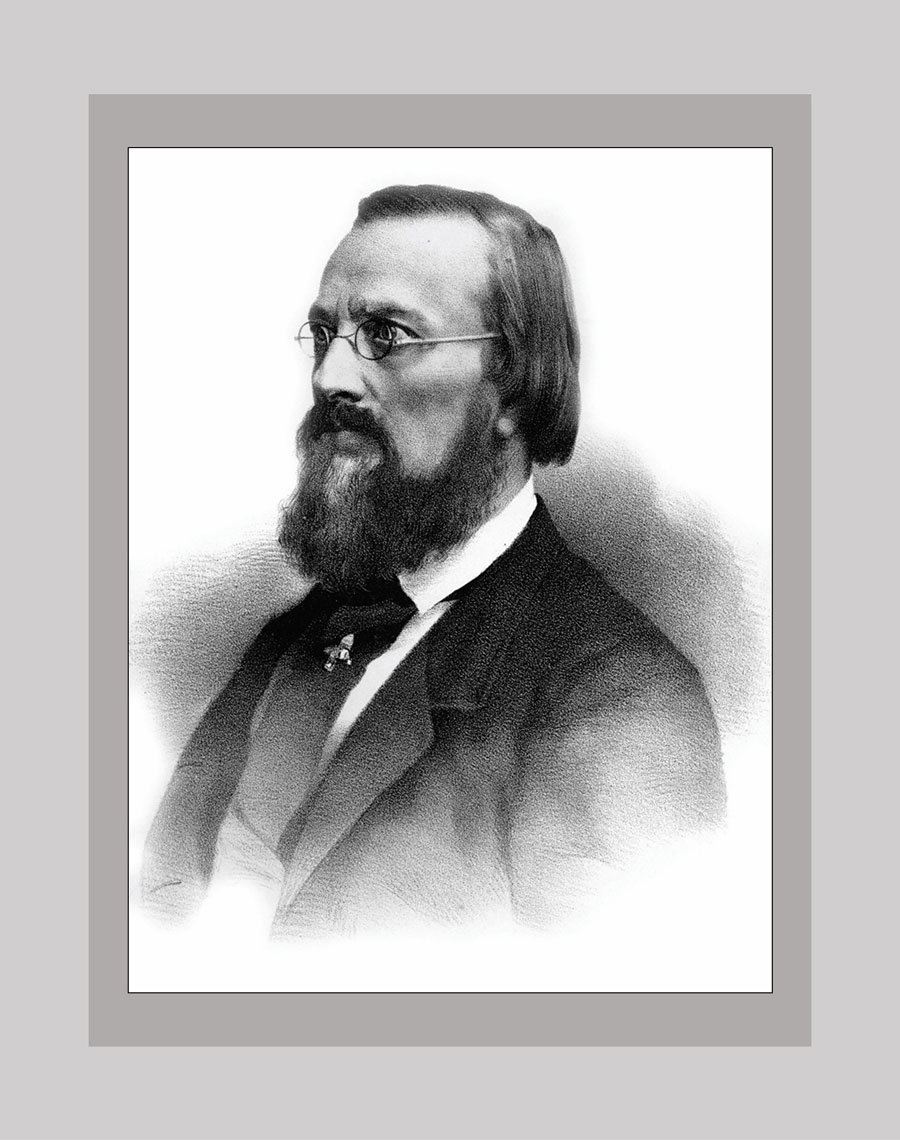

Whatever its original intent, and though not regarded as a work of historical scholarship, the Istoriia had an enormous impact on Ukrainian folklore and writers who shaped the Ukrainian national awakening. In his early writings, Taras Shevchenko, the foremost Ukrainian poet of the nineteenth century, read the work as "a quest for national liberation." The influential writers Panteleimon Kulish and Mykola Kostomarov likely picked up the "keys to the church" motif from the Istoriia and introduced it into Ukrainian literature as part of their depiction of the exploitative Jewish leaseholder.

Scholars judge that Kostomarov and Kulish, in their ambition to develop a compelling national epic narrative, amplified themes that would elicit outrage at the humiliation and oppression of the Ukrainian people. Kostomarov used the "keys to the church" motif as the master plot in Pereiaslavska nich: Trahediia (Pereiaslav Night Tragedy, 1841), a play set in 1649, and also propagated this motif in his influential histories. Thus, the persecution of Jews in the period of Khmelnytsky came to be linked not only to a narrative of economic exploitation but also national and religious humiliation. Kulish went so far as to alter traditional duma to include anti-Jewish motifs by replacing mentions of Polish landlords with "Jewish leaseholders." The celebrated Ukrainian writer Ivan Franko and the prominent Ukrainian historian Mykhailo Hrushevsky both noted these alterations and deemed them regrettable.

sources

- Serhii Plokhy, The Cossack Myth: History and Nationhood in the Age of Empire (Cambridge, 2012), 4, 6, 179, 304–306;

- Myroslav Shkandrij, Jews in Ukrainian Literature. Representation and Identity (New Haven, 2009), 11–18, 30–31;

- Myroslav Shkandrij, “There are problems in Ukraine that are challenging historians, writers, and civil society,” Hadashot, English translation on UJE website, 18 December 2019.

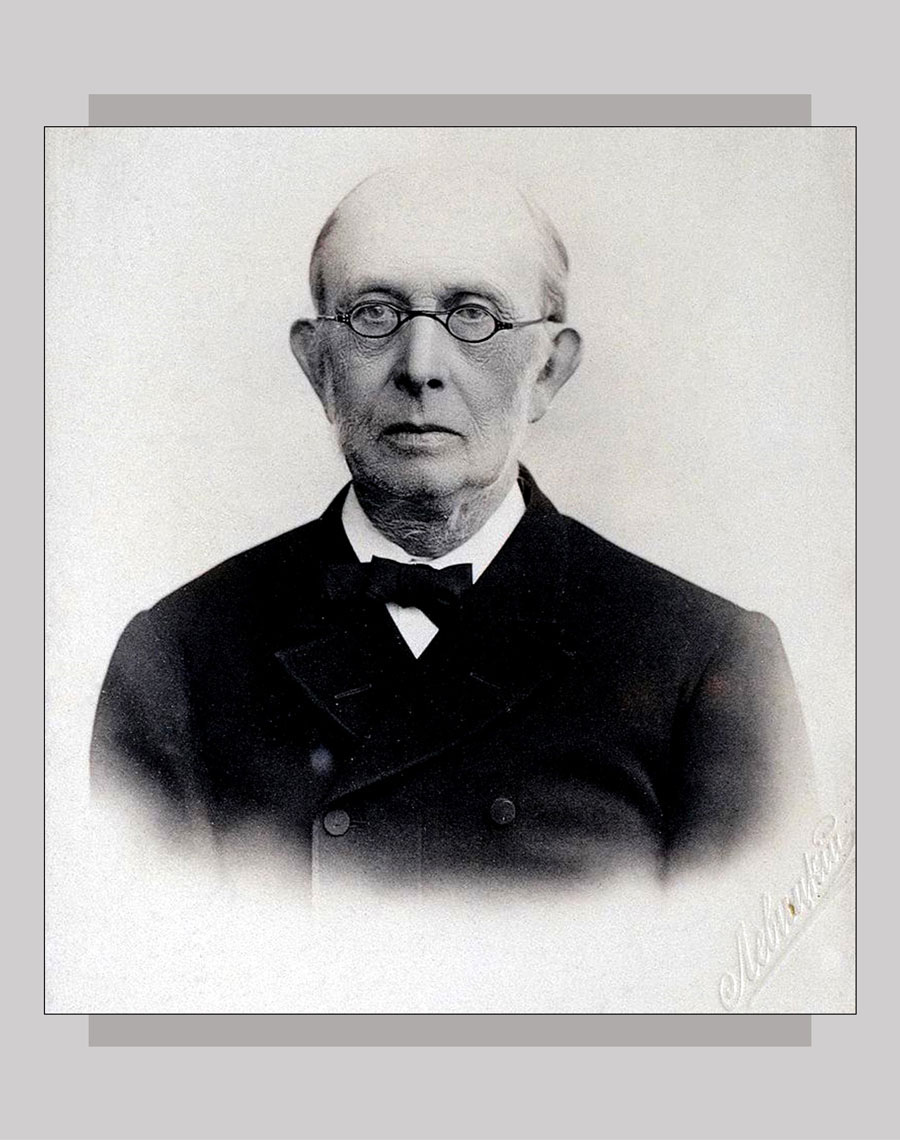

1862

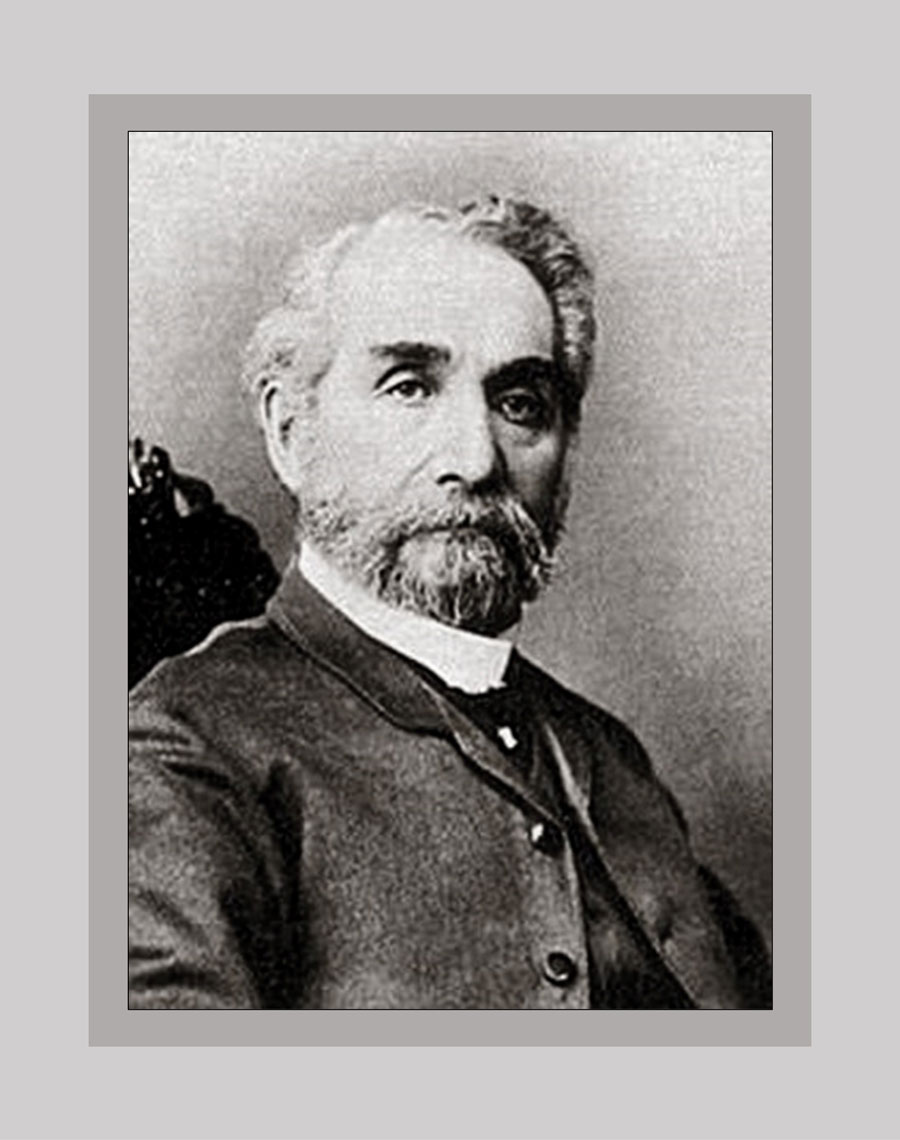

Mykola Kostomarov's article "Iudeiam" (To the Jews) — the first major Ukrainian statement concerning Ukrainian-Jewish relations — was published in the St. Petersburg Ukrainian monthly Osnova. In this article, Kostomarov levels charges against Jews as selfish and callous, supporting his argument with antisemitic tropes found in the Istoriia Rusov about the role of Jews in past social exploitation and humiliation of Ukrainians, fused with condemnation of their role in present-day injustices.

Read more...

Kostomarov accuses Jews collectively not only of lacking sympathy for Ukrainian national aspirations but also of taking advantage of the moral failings of others. His charges include that they loan money for alcohol to "the backward muzhyk" and "lead the debtor to ruin; they incite theft, and they facilitate debauchery." The accusations are generalized in a manner that leads the reader to think that one is dealing with Jews in all places and at all times.

At the same time, Kostomarov opposed the first design of the Bohdan Khmelnytsky monument in Kyiv, which depicted a Polish nobleman, a Jewish leaseholder, and a Jesuit beneath the hooves of the hetman’s horse. Kostomarov also spoke out in favour of lifting existing legal restrictions on Jews. According to the historian and statesman Mykhailo Hrushevsky, Kostomarov's subjective emotions prevented him from elucidating the causes of Ukrainian-Jewish friction adequately, although wishing to overcome it.

sources and related

- Myroslav Shkandrij, Jews in Ukrainian Literature. Representation and Identity (New Haven, 2009), 33–35;

- Myroslav Shkandrij, “There are problems in Ukraine that are challenging historians, writers, and civil society,” Hadashot, English translation on UJE website, 18 December 2019;

- Ivan Rudnytsky, "Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Nineteenth-Century Ukrainian Political Thought," in Peter Potichnyj, Howard Aster, eds. Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective (Edmonton, 1988), 70–71.

Related

Chapter 6.4 1890s–1900s (Ukrainian ethnography)

Chapter 6.5 1876–1883

Chapter 6.6 1858 (Kostomarov re: open letter)

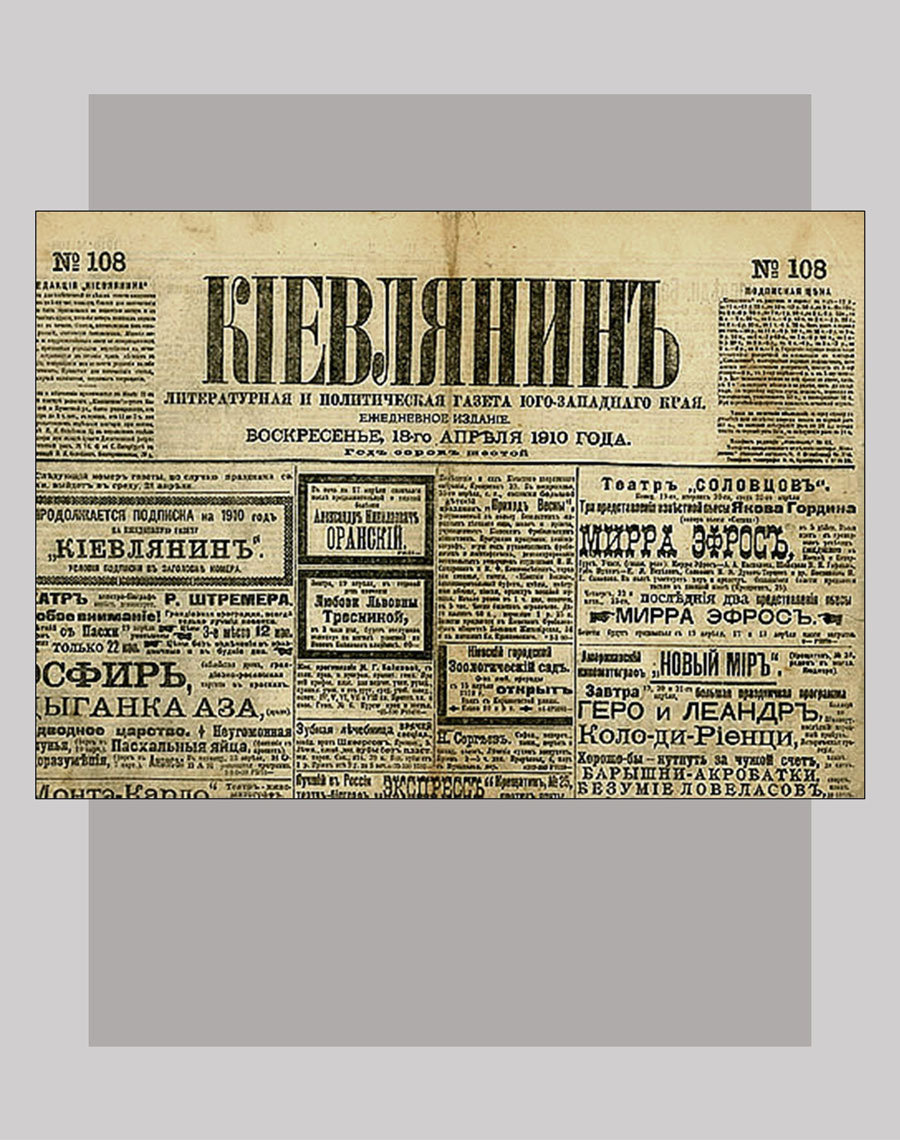

1864–1913

Kievlianin, a Russian-language newspaper subsidized by the tsarist government, noted for its rigid anti-Ukrainian policy and its extreme hostility to Jews, was founded in Kyiv by Vitalii Shulgin. Its editorials attacked any expression of Ukrainophilism as Ukrainian separatism. Its views on Jews, as articulated by Shulgin in 1870, were profoundly antisemitic: "…many horrendous things flourish [among the Jewish people] — the obscurantism of diabolical superstition and fanaticism — and many thousands of Jewish heads are crammed with perverted conceptions, but the moral responsibility for all this mess falls exclusively upon Jewish institutions and on the Jewish government."

Read more...

In 1869, Kievlianin undertook a major campaign against the evils of Jewish lease holding. This campaign probably induced the local governor, Prince Dondukov-Korsakov, to propose measures to forbid Jews to lease or purchase estates in his jurisdiction and re-introduce restrictions on Jews trading in liquor in rural areas of the Pale.

Kievlianin continued its anti-Jewish campaign until Shulgin's death and, under the editorship of his son Vasilii(1878–1976), into the 1910s. Both father and son were right-wing Russian monarchists. In 1913, however, Vasilii strongly criticized the Russian government for its role in the Beilis blood libel trial.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. I, 404, 426, 429;

- "Kievlianin," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1988).

1871

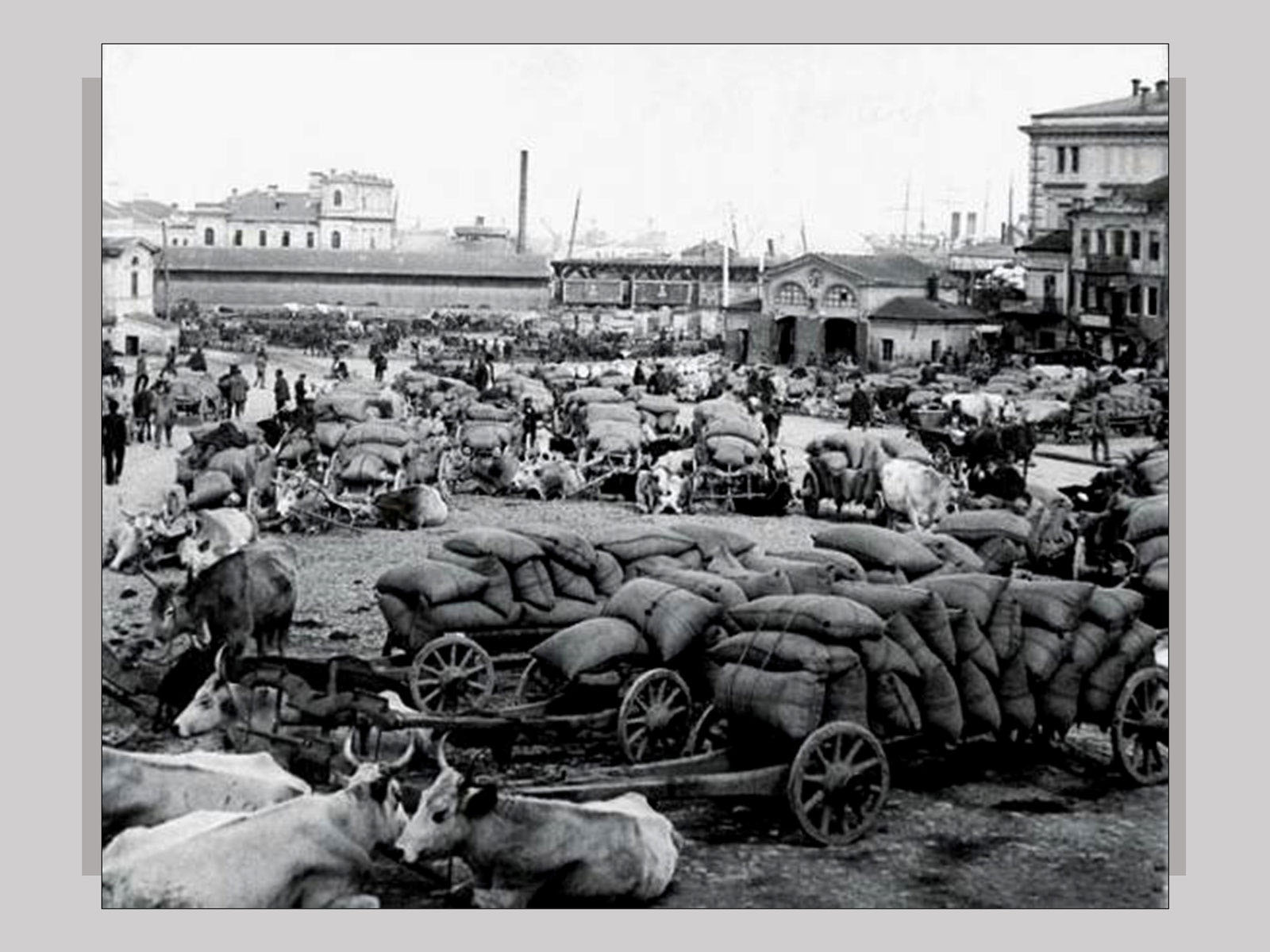

A pogrom was carried out during Holy Week by a mob of Greeks and Russians against Jews in Odesa, a leading centre of Russian acculturation. Anti-Jewish pogroms had also occurred in 1821 and 1859. The 1871 pogrom was motivated by growing commercial rivalry in the grain trade between the Greek community and Jews, and also religious antipathy towards Jews. As reported by the Governor-General of New Russia, Count Kotsebue: "In the crowds of Christians there were often heard the words 'the Jews offended our Christ, they grow rich, and they suck our blood'."

Read more...

The rioting and destruction — in which eight people died, twenty-one were seriously injured, and thousands were rendered homeless (especially in the Jewish suburb of Moldavanka) — was compounded by Kotsebue's response and that of the city's non-Jewish intellectuals, blaming Jews for starting the violence.

The disturbing events and the authorities' lack of support during the four-day pogrom caused Jewish leaders to reappraise their faith in eventually overcoming what they now saw as rooted Judeophobia. A noteworthy example is the publicist/writer Peretz Smolenskin, who began to question the possibility of Jewish integration into the broader Christian society and became among the first to promote Jewish nationalism.

sources

- John Klier, "Pogroms," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010);

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. I, 428;

- Zipperstein, The Jews of Odessa: A Cultural History, 1794–1881 (Stanford University Press, 1986), 114–128.

1876–1883

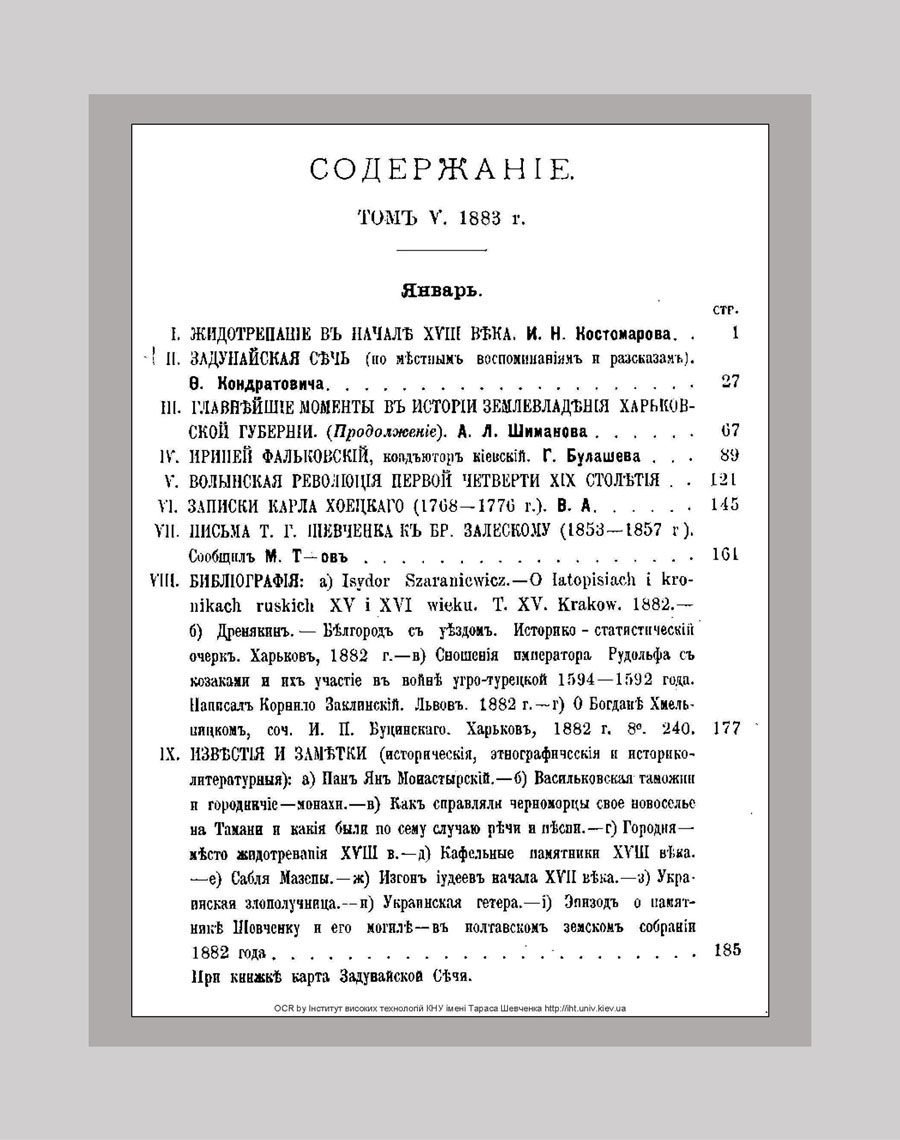

When Professor Daniel Khvolson republished his refutation of the blood libel in 1879, he was attacked in the newspaper Novoe Vremya by the historian Mykola Kostomarov, who claimed that "some" Jews engaged in ritual murder. Three years earlier, Kostomarov had given his scholarly imprimatur to a book accusing 'Jewish sectarians' of ritual murder, published by the disreputable and defrocked priest Hipolit Lutostański. In 1883, Kostomarov published "Zhidotrepanie v nachale XVIII veka" (Beating up zhids in the beginning of the eighteenth century), a fictionalized account of a Jewish ritual murder accusation in early eighteenth-century Ukraine, which led to a pogrom — clearly implying an analogy to the recent pogroms of 1881–82.

sources and related

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. I, 391, 435; vol. II, 10.

Related

Chapter 6.4 1890s–1900s (Ukrainian ethnography)

Chapter 6.5 1862 (Mykola Kostomarov)

Chapter 6.6 1858 (Kostomarov re: open letter)

1878–1881

Antisemitic rhetoric entered public discourse during this period, portraying Jews as a threat to the social order, whether it was for their supposed embodiment of revolutionary socialism, their 'nihilism,' or destructive capitalism.

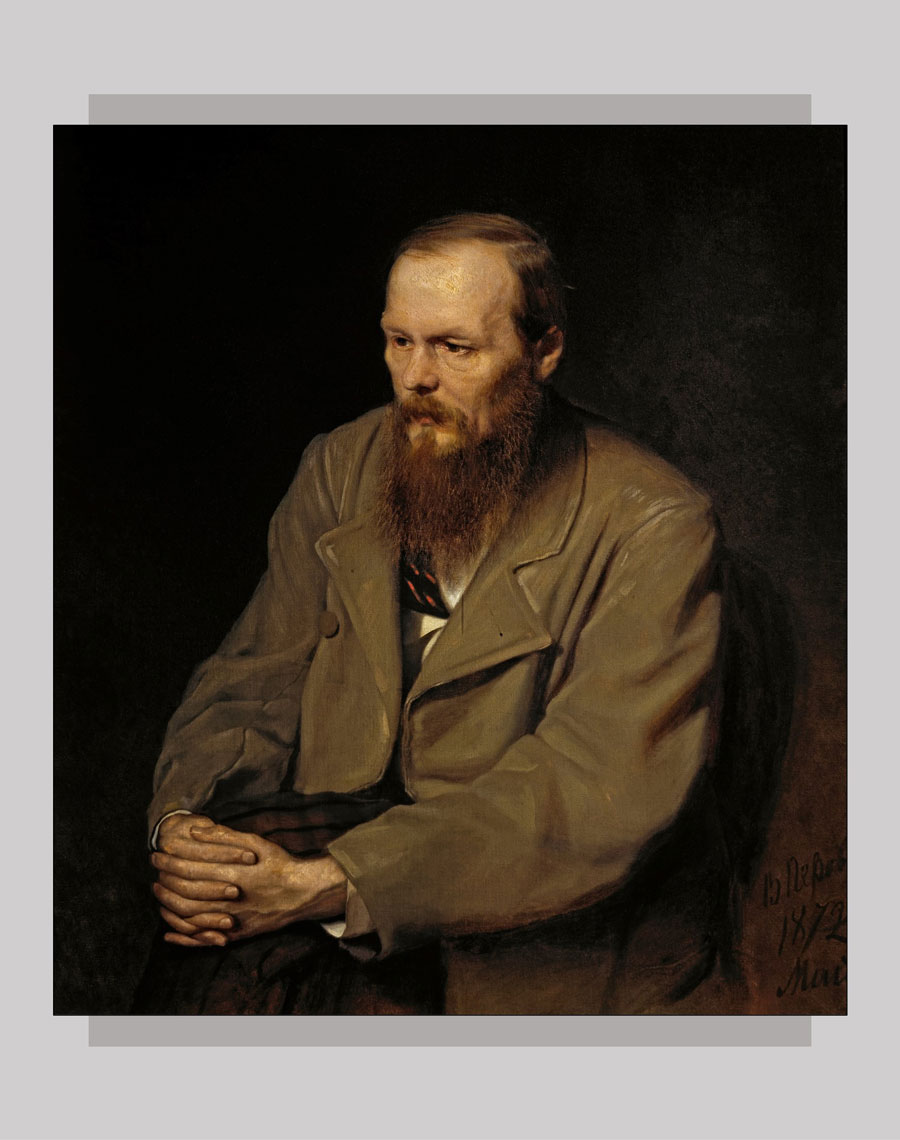

A letter to the editor in 1878 by the eminent Russian writer Fedor Dostoevsky was published in the Judeophobic newspaper Grazhdanin, blaming Jews collectively for the growing revolutionary unrest in the Empire. The letter stated that "Odesa, the city of Yids, is the centre of our rampant socialism" — though, at the time, Jewish participation in the socialist revolutionary movement was very small-scale.

Read more...

An 1879 article by V. Varzer, "Jewish Leaseholders in Chernihiv Province," published in the influential St. Petersburg monthly Otechestvennye zapiski, made the exaggerated and incendiary claim that Jewish leaseholders, "accidental people, with no ties to or respect for the land," already controlled 40 percent of the land in the province and exploited the peasants under their control. Public discourse during this period often compared Jews with kulaks, originally petty traders but increasingly in the post-emancipation era seen as rapacious peasants intent on acquiring land at the expense of their neighbours.

In 1880 Novoye vremya, a respected conservative newspaper in St. Petersburg, argued that the essence of Judaism was 'cosmopolitanism' — that for Jews, the whole world existed as an object of exploitation, that capitalism and socialism were simply parallel paths to the same goal.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. I, 432–434.

1880s–1890s

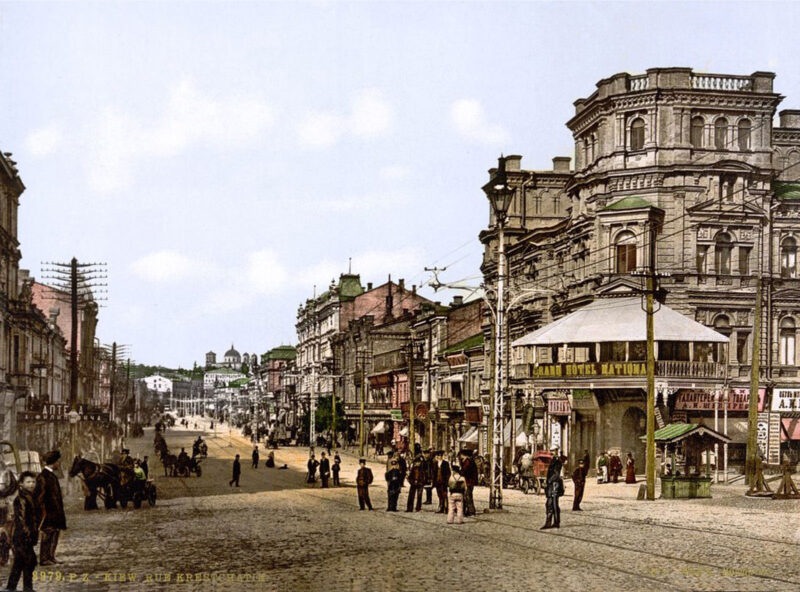

While the rise in Kyiv of a commercial elite, which included a few Jewish entrepreneurs (such as the Brodsky family), created a spirit of philanthropy, cooperation, and vibrant cultural life, it also provoked antisemitic reactions. Complaints came from both intellectuals and the city's growing leagues of workers about what they considered was overcharging for basic commodities and services (i.e., sugar, municipal utilities).

Lesser merchants of Orthodox Ukrainian background and residents of Kyiv's impoverished peripheral working-class neighbourhoods began to form associations around such grievances.

Read more...

By the 1890s, class-conscious thought and anti-capitalist sentiment grew more powerful in the city. However, these groups overlooked the prominent elite Ukrainian and Russian families (such as the Tereshchenkos and the Bobrinskiis) in the local capitalist complex, focusing almost exclusively on the success of Jewish entrepreneurial families and blending their anti-capitalist criticism with antisemitic rhetoric.

In newspapers, city council meetings, and voluntary associations, antisemitic political activists began to speak of a Jewish conspiracy and demanded that the "Judeo-capitalist yoke" be destroyed. Some of Kyiv's populist, antisemitic activists dismissed liberal principles such as civic equality as a Jewish ploy to achieve domination over hapless peasants. Others participated in anti-Jewish incitement alongside local right-wing Russian nationalist groups, despite their national and ideological differences.

sources

- Faith Hillis, Children of Rus': Right-Bank Ukraine and the Invention of a Russian Nation (Ithaca and London, 2013), 127–138.

1881–1884

Anti-Jewish Pogroms

A wave of pogroms broke out in the southwestern provinces of the empire, prompted by a rumour that Jews had assassinated Tsar Alexander II and that, as a result, the government supposedly had authorized attacks on Jews. Some surviving members of the revolutionary Narodnaia Volia (People's Will) — the group that actually carried out the assassination of the tsar as part of its agenda to destabilize society — supported the pogroms. Though the Russian authorities feared that the pogroms might encourage further disruptions by the revolutionaries, they did not intervene in a concerted way to stop the violence at the start.

Read more...

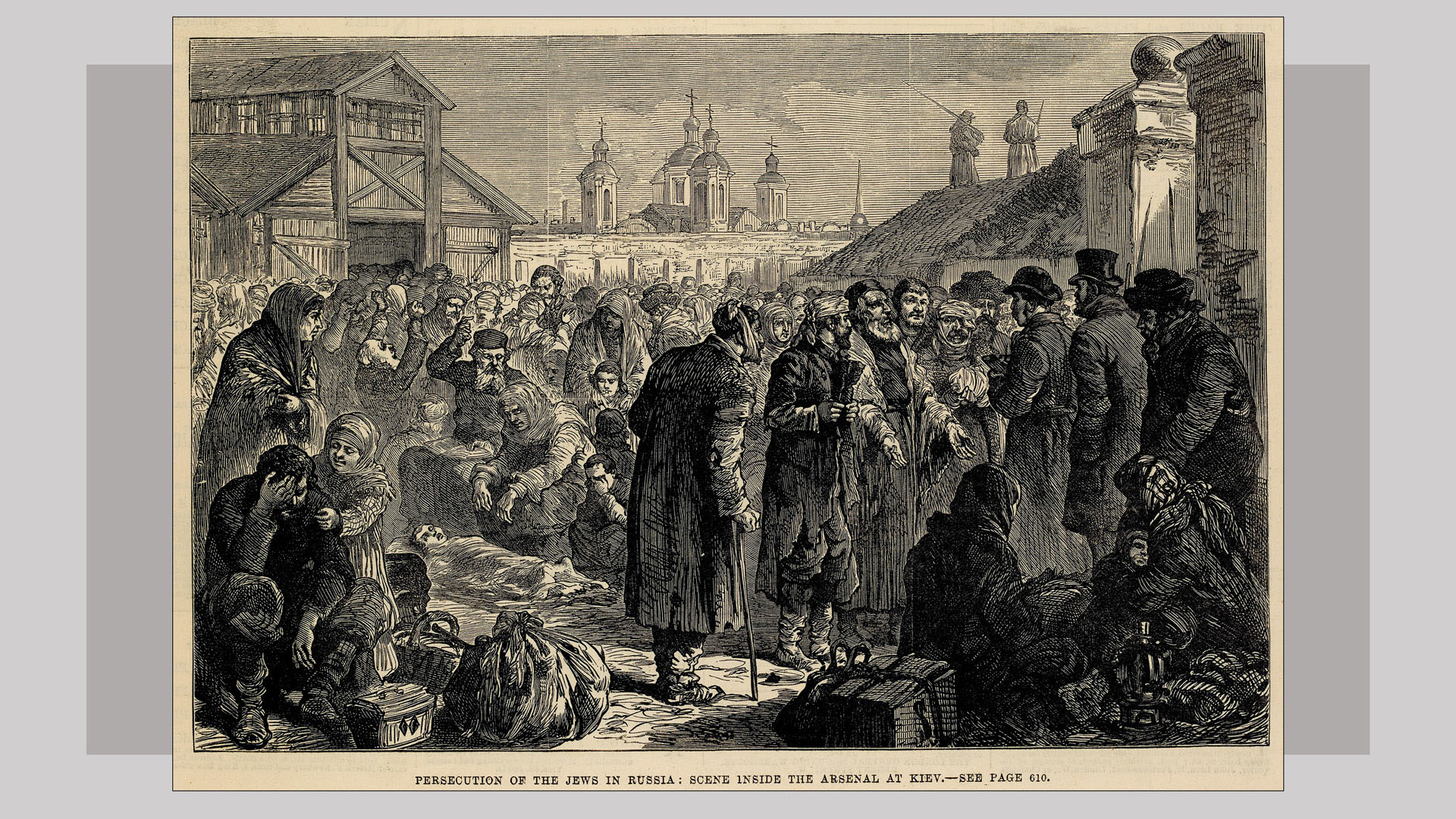

The pogroms — referred to by Jewish writers as "southern tempests" — were concentrated in Dnieper Ukraine, occurring first in Elisavetgrad (now, Kropyvnytskyi), then in Kherson province. A pogrom in Kyiv followed, which lasted three days. The violence then spread to villages in the Kyiv region and surrounding provinces. Of 259 pogroms, 219 occurred in villages, 4 in Jewish agricultural colonies, and 36 in cities and small towns. The violence consisted primarily of looting, as gangs of local townspeople and peasants plundered Jewish homes and shops. But there were also many rapes, at least 35 deaths, and many more injuries.

Officials and investigative commissions at the time explained the pogroms as a reaction to the predatory economic practices of Jews, which harmed the peasantry and common people. This theme was propagated by the Judeophobic press and echoed in government circles, including by the Governor-General of Kyiv and the new Minister of the Interior, Count Nikolay P. Ignatyev, who recommended renewing and expanding economic restrictions on Jews. This explanation of the pogroms proved particularly convenient for the ruling elite and Ignatyev himself, who wished to discredit the liberal reforms of the previous reign and encourage the new tsar's autocratic tendencies.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. II, 5;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 361;

- Shmuel Ettinger, "The Modern Period," in A History of the Jewish People, H.H. Ben Sasson (Cambridge, Mass., 1976), 881–883;

- John Klier, Shlomo Lambrosa, eds., Pogroms: Anti-Jewish Violence in Modern Russian History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 40–43 ff.

1882

The tsarist authorities' response to the 1881 pogroms was to establish special commissions in each district of the Pale of Settlement to examine the harms caused by Jewish economic activity. As these commissions were composed of representatives of groups hostile to and competing with Jews, their overall conclusion was that increased economic restrictions must be imposed on Jews.

The resulting anti-Jewish "May Laws," proposed by the minister of the interior Count Nikolay P. Ignatyev, were approved by Tsar Alexander III as temporary measures in May 1882 but lasted until 1917.

Read more...

These laws renewed and expanded anti-Jewish restrictions that had been lifted in the Great Reforms of the 1860s, including prohibiting any new settlement of Jews in rural areas (except for Jewish agricultural colonies). The May Laws also reintroduced numerus clausus in high schools and universities and quotas in the professions. The restrictive measures were presented as "protection of the primary population against Jewish exploitation."

Some officials opposed the draconian measures and were alarmed at the impact they might have on Russia's image abroad and on the economic stability of the empire. More balanced findings and recommendations were presented by another special commission but rejected by Tsar Alexander III, who held a hostile view of Jews. The tsar was likely influenced by his tutor Konstantin Pobedonostsev, who stated that restricting the harmful activities of the Jews was for their own good, purportedly to protect them against further outbursts from resentful peasants. In fact, these regulations severely affected the livelihood of Jews, the majority of whom were already struggling to eke out a living in the overcrowded small towns of the Pale.

The findings of current scholarship are that the 1881–1882 pogroms were not planned or approved by the authorities. However, the subsequent anti-Jewish legislation of the state contributed to the nearly universal perception at the time that the attacks were either contrived by or at least condoned by the tsarist regime.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. II, 8, 13–14;

- Shmuel Ettinger, "The Modern Period," in A History of the Jewish People, H.H. Ben Sasson (Cambridge, Mass., 1976), 881–885;

- Michael Stanislawski, "Russia: Russian Empire," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1884–1890s

The authorities re-introduced regulations restricting education and vocational training of Jews and zealously enforced anti-Jewish measures. In 1884 the only Jewish vocational school in the Russian Empire, functioning in Zhytomyr for over twenty years, was shut down. The justification for closing the school was that it afforded Jews an unfair advantage since the main population did not have such schools. In 1885, Kharkiv's Technological Institute applied a 10 percent quota for Jews. In 1887, a ministerial order established country-wide educational quotas for Jews in secondary schools and universities, as follows: 10 percent in the Pale, 5 percent in the rest of the country, and 3 percent in Moscow and St. Petersburg. Particularly burdensome was the 1886 regulation that imposed heavy fines on families of young Jews who failed to report for military service — many of whom had already emigrated, legally or otherwise, to North America.

Read more...

Expulsions of individuals or entire groups of Jews from Kyiv and other large cities became a regular occurrence. The police continually harassed Jews living outside the Pale, extracting random payments and organizing special night raids. Often it was because the authorities decided that a particular economic occupation (such as a specific category of artisans) would no longer count in granting Jews residence rights in the city. According to historian Simon Dubnow, around 2,000 Jewish families were expelled from Kyiv in 1886 (and around 20,000 Jews were summarily expelled from Moscow in 1891). There is little doubt that the clause in the 1882 May Laws forbidding "new settlement" by Jews in rural areas, followed by the educational, occupational, and residential restrictions in the next decade, contributed to the impoverishment of millions of the empire's Jews.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. II, 15;

- Shmuel Ettinger, "The Modern Period," in A History of the Jewish People, H.H. Ben Sasson (Cambridge, Mass., 1976), 883–885;

- Natan Meir, Kiev: Jewish Metropolis (Bloomington and Indianapolis, 2010), 103–106.

1903

Anti-Jewish violence erupted on Easter Day in Kishinev in the Empire's far southwestern province of Bessarabia. Forty-seven Jews were killed, hundreds more were raped or maimed, 700 houses were burnt, and 600 shops were looted. The Kishinev pogrom resonated across the region and provoked worldwide outrage, especially when it became known that the authorities did not intervene until the third day. Historians consider that it became the archetypal pogrom, beyond the scale of the suffering itself. In the following year, 43 more violent incidents in the region resulted in 36 deaths, many wounded, and much destruction of property. Almost half of these incidents were linked to ritual murder accusations, market brawls, tensions during Jewish and Christian religious holidays, and a general breakdown in law and order.

Read more...

Historians have long believed that the instigators of the Kishinev anti-Jewish violence were officials in the Russian imperial government. Recent research points instead to a clutch of local activists closely linked to a rabidly antisemitic newspaper, abetted by right-wing student radicals. However, it is clear that the police and local authorities did not act decisively to stop the violence or punish the perpetrators. Their apathetic response signalled to those who wanted to attack Jews that they could do so with impunity, setting the stage for the much more violent wave of pogroms that followed in the next two years across the Russian Empire.

The Kishinev pogrom had deeply significant consequences. It undermined the belief then held by many Jews that integration into the wider society was a realistic aspiration. It stimulated emigration, Zionism, and the organization of Jewish self-defence units that served as models for responding to later pogroms.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. II, 47–49;

- Michael Stanislawski, "Russia: Russian Empire," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010);

- Wolf Moskovich, "Kishinev," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010);

- John Klier, "Pogroms," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010);

- Steven J. Zipperstein, Pogrom: Kishinev and the Tilt of History (2018), 11, 90–99.

1903–1912

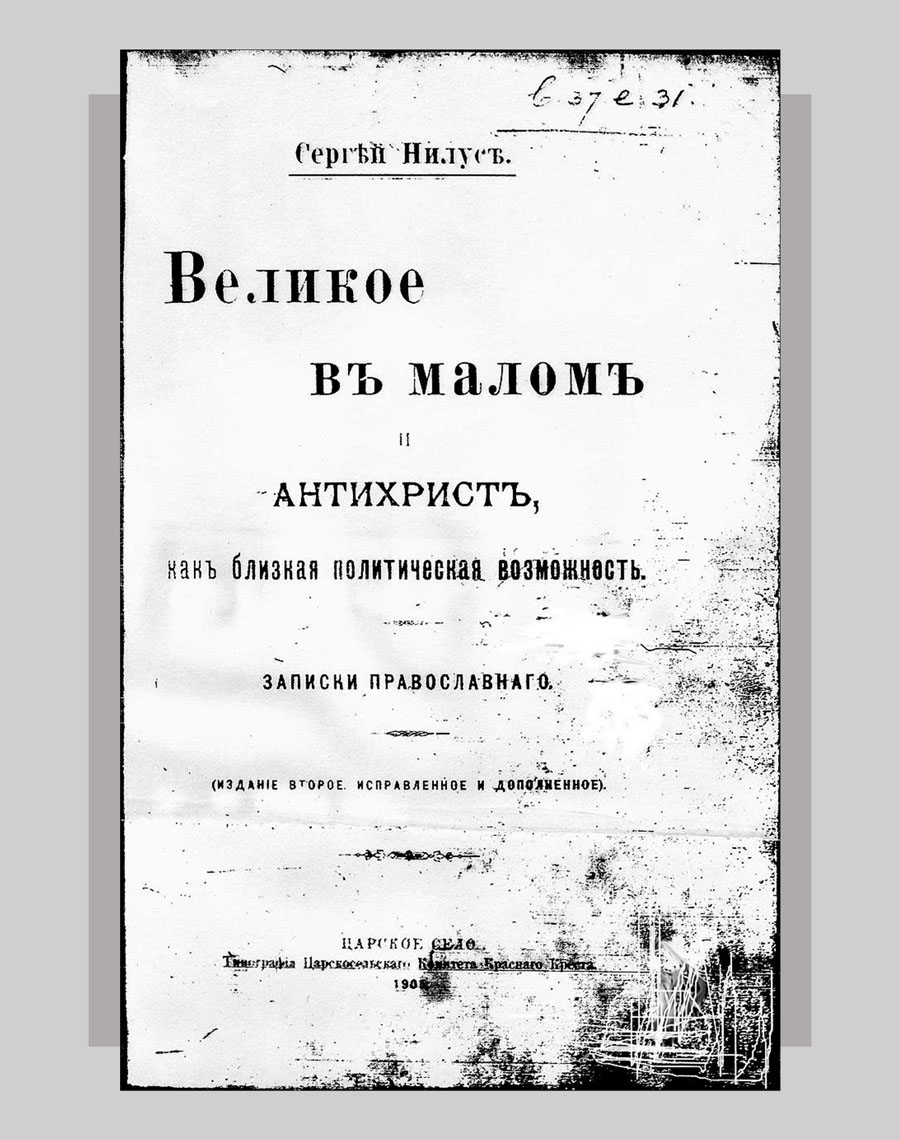

The notorious forgery known as The Protocols of the Elders of Zion — the most widely distributed antisemitic publication of the twentieth century (and still extant) — was created and propagated with the encouragement of individuals in the tsarist secret police. The Protocols, however crude, propagated the myth that Jewish leaders held secret meetings at which they conspired to dominate the world, economically and politically. In this account, Jews are depicted not only as anti-Christian but also as responsible for the evils of liberalism, capitalism, socialism, and all other ills of modernity.

Read more...

Portions of The Protocols were published in August–September 1903 in serialized form in Znamya (The Banner), an openly antisemitic Saint Petersburg daily newspaper. The newspaper's publisher, Pavel Krushevan, was a Russian ultra-nationalist monarchist and a key instigator of the Kishinev pogrom four months earlier. The Russian mystic Sergei Nilus published a fuller version of The Protocols in 1905 and circulated further editions in the following decade.

The antisemitic motifs in The Protocols resonated with the Black Hundreds who instigated anti-Jewish pogroms in Ukrainian lands in 1905–1906 and the Beilis trial in 1911–1913. After the Russian Revolution, The Protocols were widely disseminated in Europe and beyond by Russian émigré monarchists who sought to discredit the Bolsheviks by linking them with Jews. The Protocols' key motifs nurtured the Judeo-Bolshevik myth — the "belief" that Bolshevism is the product of an international Jewish conspiracy to undermine and destroy the Christian world and specific European nations from within. This myth was used by both the pro-monarchist Russian White Army and the troops of the fledgling Ukrainian state to justify murderous anti-Jewish pogroms in 1918–1919. It was also a central feature of German propaganda in Eastern Europe in preparation for and during World War II, fuelling radicalized anti-Soviet nationalism in the 1930s–early 1940s, including in Ukraine.

sources

- Daniel Pipes, Conspiracy: How the Paranoid Style Flourishes and Where It Comes From (Simon & Schuster, 1997), 85–87;

- Wayne Allensworth, The Russian Question: Nationalism, Modernization, and Post-Communist Russia (Rowman & Littlefield, 1998), 126–129;

- Norman Cohn, Warrant for Genocide: The Myth of the Jewish World Conspiracy and the Protocols of the Elders of Zion (London, 1996);

- Stephen Eric Bronner, A Rumor about the Jews: Antisemitism, Conspiracy, and the Protocols of Zion (Oxford, 2003);

- Paul Hanebrink, A Specter Haunting Europe: The Myth of Judeo-Bolshevism (Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2018).

1905–1906

A wave of pogroms swept over 600 towns and villages, almost all in the Pale of Settlement, resulting in over 3,100 deaths, 17,000 wounded, and massive destruction of property. Nearly 87 percent (575) of the pogroms took place in the Ukrainian provinces of Chernihiv, Poltava, Katerynoslav, Kherson, Podolia, Kyiv, and Bessarabia.

Read more...

The violence was directly related to the government's struggle against the growing revolutionary movement and the concessions made to the revolutionaries by Tsar Nicholas II in the October Manifesto. More than four-fifths of the pogroms occurred in the sixty days following the issuing of the manifesto. During this period, large sections of the administration regarded 'the Jews' as the principal instigators of the revolution. In fact, Jews were a small minority among the revolutionary leaders.

Historians have documented the central government's complicity in the pogroms and the reluctance of provincial and local officials to act to control the violence. Other critical factors fueling the violence include the emergence of extremist right-wing political organizations that recruited government officials to their cause and the establishment of pro-monarchist vigilante groups, known as the Black Hundreds. These groups orchestrated and carried out most of the attacks, with support from sympathizers within the imperial state bureaucracy, the military, the police, and the conservative press (foremost, the newspaper Kievlianin), which repeatedly blamed revolutionary activity on Jews. Although Jews were the primary target, the Black Hundreds also used violence to intimidate liberals, democrats, socialists, Ukrainian cultural activists, and students suspected of supporting the revolutionary movement.

Research indicates that there were differing approaches within the government, especially in the later stages. Some officials encouraged or condoned demonstrations that supported the old order; some officials merely allowed them to take place, while others took action to prevent the violence from getting out of hand.

Different dynamics drove pogroms against Jews in the Donbas region in 1905. Violence was part of everyday life in workers' settlements' ethnically diverse, hard-drinking, and predominately male environment. Another factor was mass political mobilization, as both right- and left-wing political forces tried to rally the industrial proletariat in support of their respective causes, at times using antisemitic rhetoric. As economic and political frustrations increased, so did the workers' discontent with industrialists, the government, and the revolutionary leaders themselves — some of whom were Jewish. At times, the discontent degenerated into violence against Jews.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford and Portland, 2010), vol. II, 52, 54–57;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto: Second Edition, 2010), 361;

- John Klier, Shlomo Lambrosa, eds., Pogroms: Anti-Jewish Violence in Modern Russian History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 224–225, 240;

- Roman Senkus, "Union of the Russian People," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1993);

- Charters Wynn, Workers, Strikes, and Pogroms: The Donbass-Dnepr Bend in Late Imperial Russia, 1879–1905 (Princeton University Press, 1992).

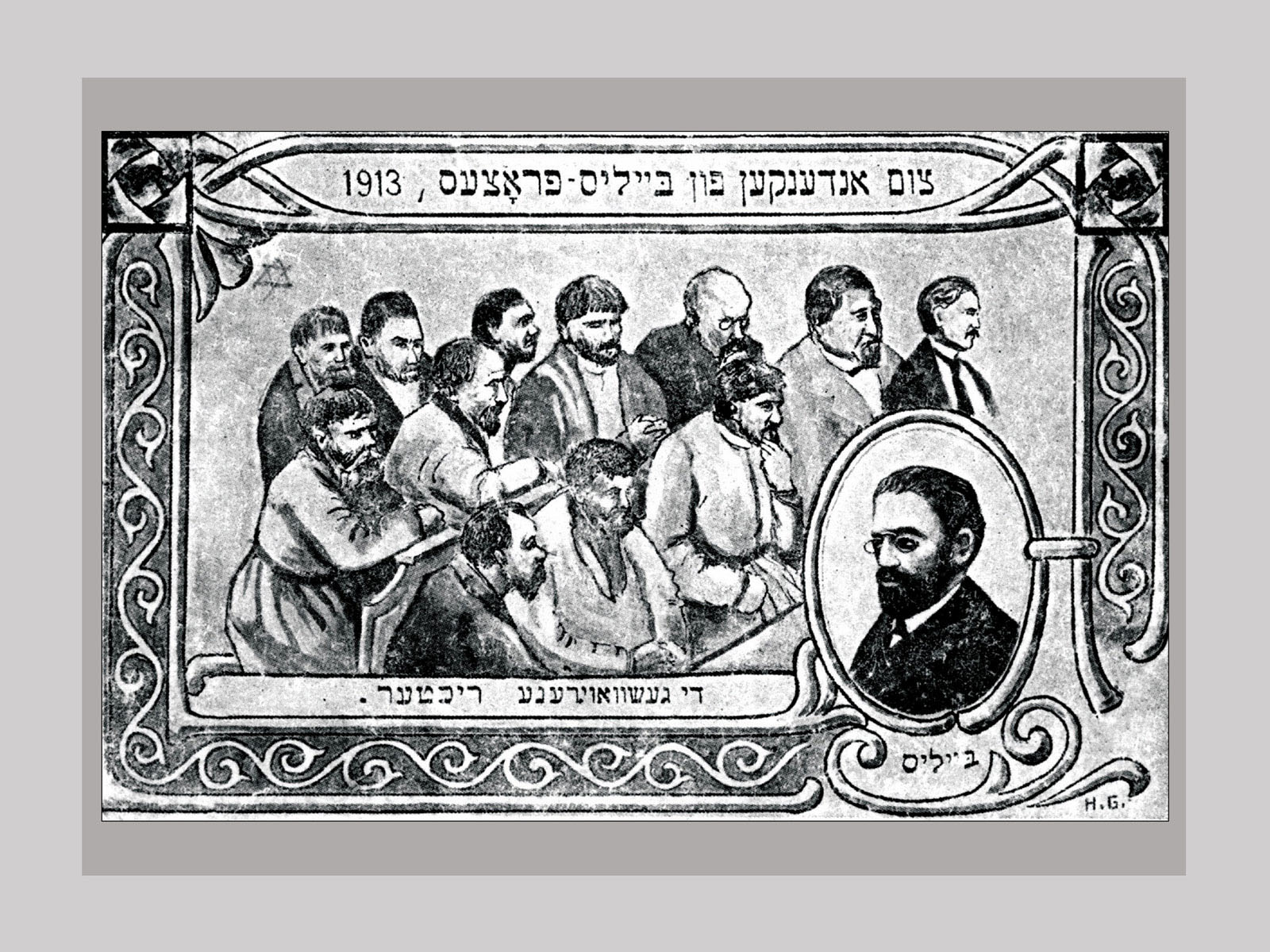

1911–1913

The Beilis Trial

Mendel Beilis, a Jewish superintendent at a brick factory in Kyiv, was falsely accused of killing the Christian boy, Andrei Yushchinsky, for ritual purposes. Documentary evidence indicates that the instigators of the case were fanatical antisemites in the office of the Kyiv prosecutor and their supporters in the imperial bureaucracy, in particular the police and the judiciary.

Read more...

Although the police knew the identity of the actual murderers, they cooperated with the officials in the Ministry of Justice and, for two years, prepared testimonies of various underworld figures and "experts" in support of the accusation. The investigation and trial attracted worldwide attention. It shook and divided society within the Russian Empire on the basis of antisemitic sentiments and opposition to such sentiments, in a manner comparable to France's Dreyfus Affair.

In the end, the Kyiv court acquitted Beilis after deliberations by a peasant-based jury, though finding nonetheless that a ritual murder had taken place. The authorities maintained an antisemitic stance, even after the verdict. As stated by Tsar Nicholas II, echoing the view expressed by the Minister of Justice Ivan Shcheglovitov: "It is certain that there was a ritual murder. But I am happy that Beilis has been acquitted, for he is innocent."

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. II, 72–74;

- Shmuel Ettinger, "The Modern Period," in A History of the Jewish People, H.H. Ben Sasson (Cambridge, Mass., 1976), 887–888.