1772–1897

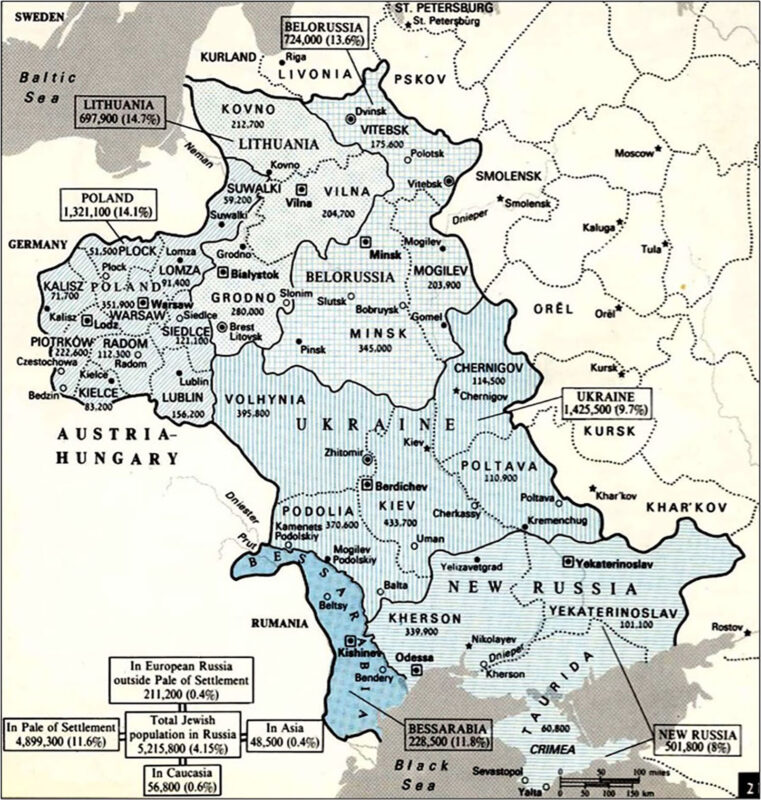

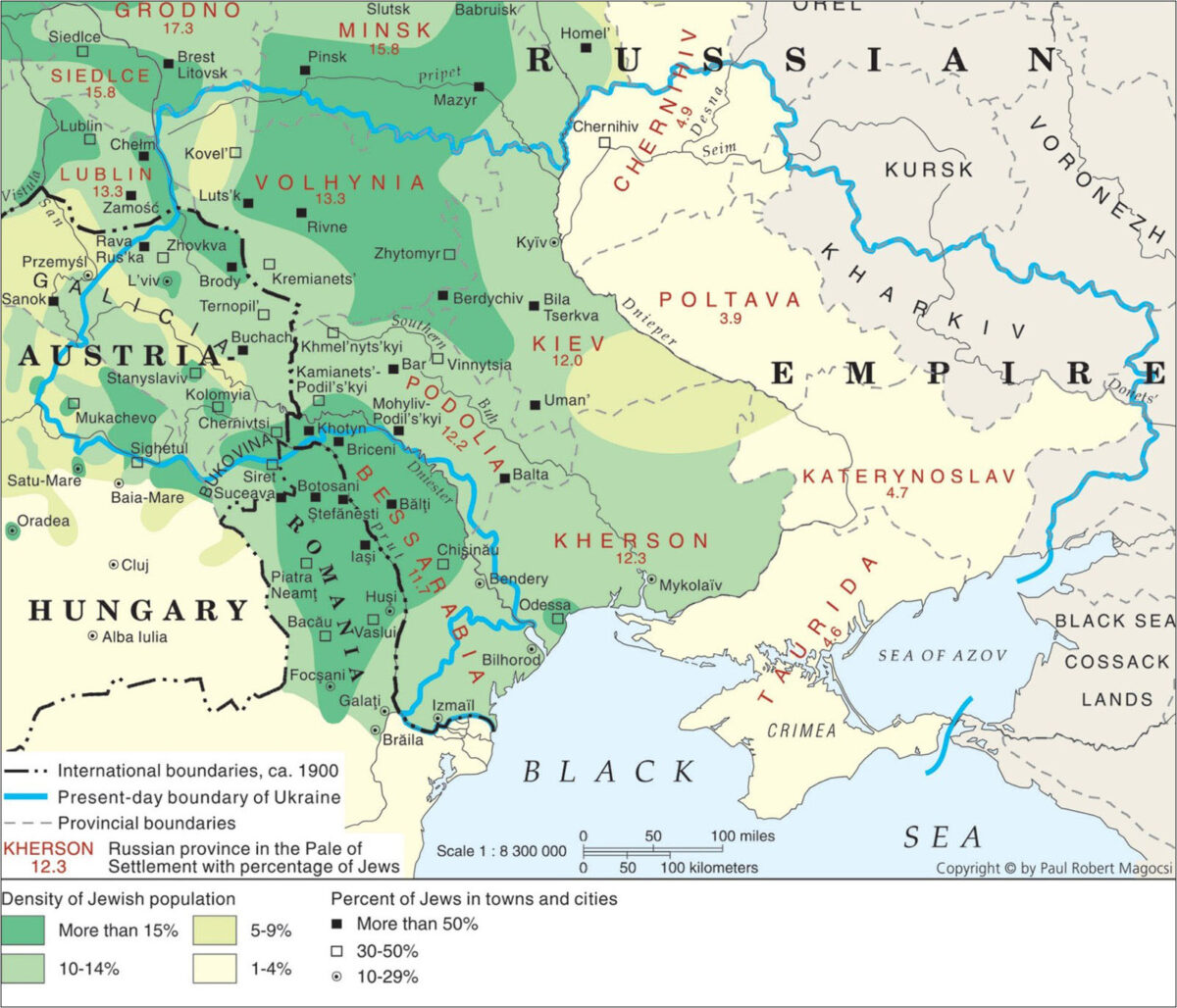

While no accurate statistics exist for the period before 1897, the best estimates suggest that there were approximately one million Jews in the Russian Empire after the partitions of Poland in the mid-1790s. In Dnieper Ukraine, their numbers grew from over 300,000 at the end of the eighteenth century to 900,000 in the middle of the nineteenth century to over two million in 1897. The vast majority lived in the Right Bank, reflecting the preference of the tsars to confine Jews to the territories acquired from the partitioned Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. These territories, which came to be known as the Pale of Settlement, included the tsarist provinces in what is today Poland, Lithuania, and Belarus, as well as all the provinces of Dnieper Ukraine, except for Kharkiv. A large proportion of the Jews lived in regions where Greek Orthodox Ukrainians were the majority population.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, Second Edition, 2010), 358;

- Michael Stanislawski, "Russia: Russian Empire," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1783–1860s

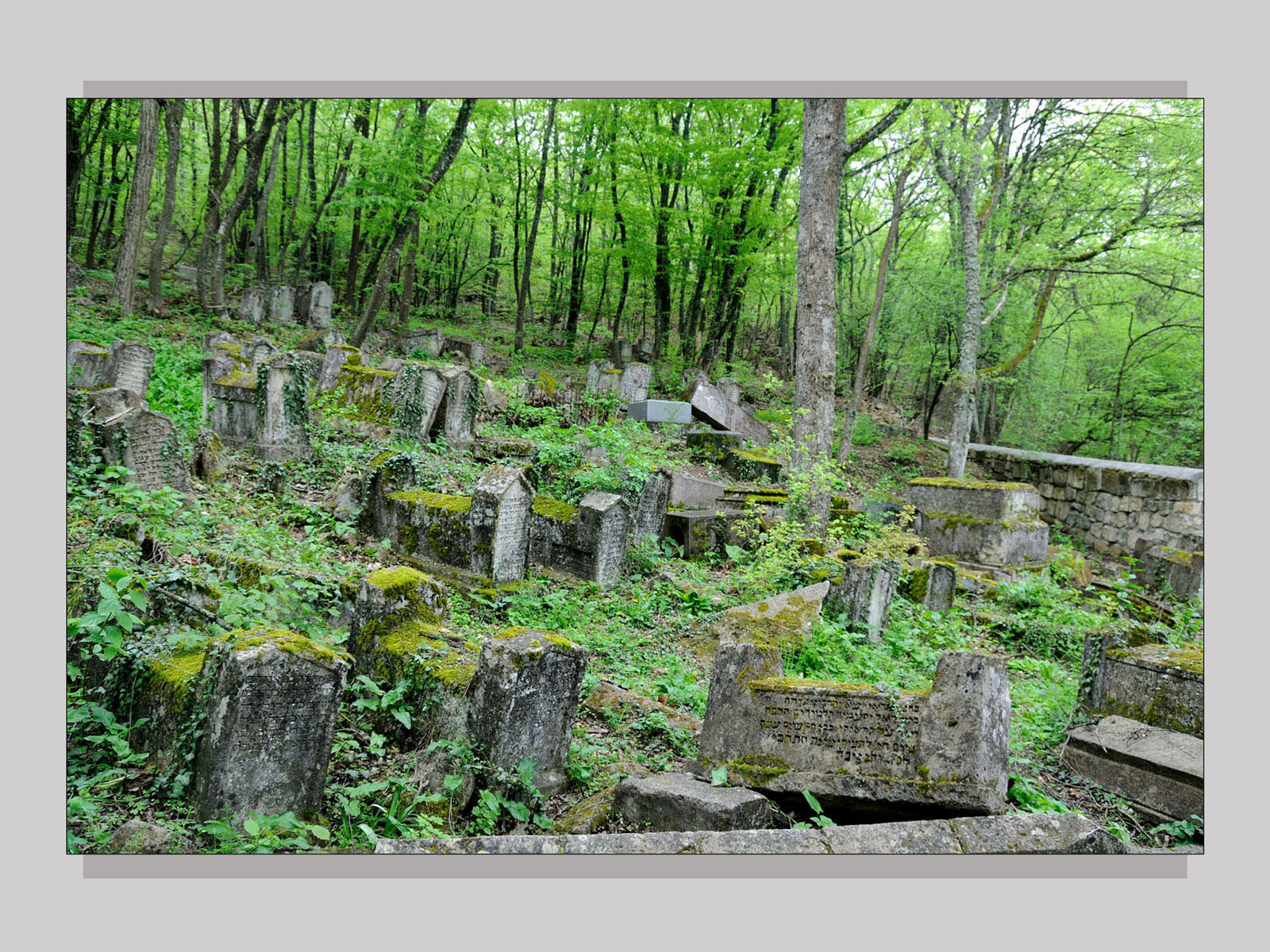

With Russia's annexation of the Crimea in 1783 and the incorporation of parts of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth into Russia in 1772–1795, most Karaite settlements in Eastern Europe became part of the Russian Empire, as did the Krymchaks (the Rabbinite Jews of the Crimea). The number of Karaites and Krymchaks in the Russian Empire was very small and concentrated in the Crimea. In 1897, there were 9,725 Karaites, of whom 5,400 lived in the Crimea, and 3,481 Rabbinite Jews (whose mother tongue was Turkish-Tatar), of whom 95 percent lived in the Crimea.

1815–1861

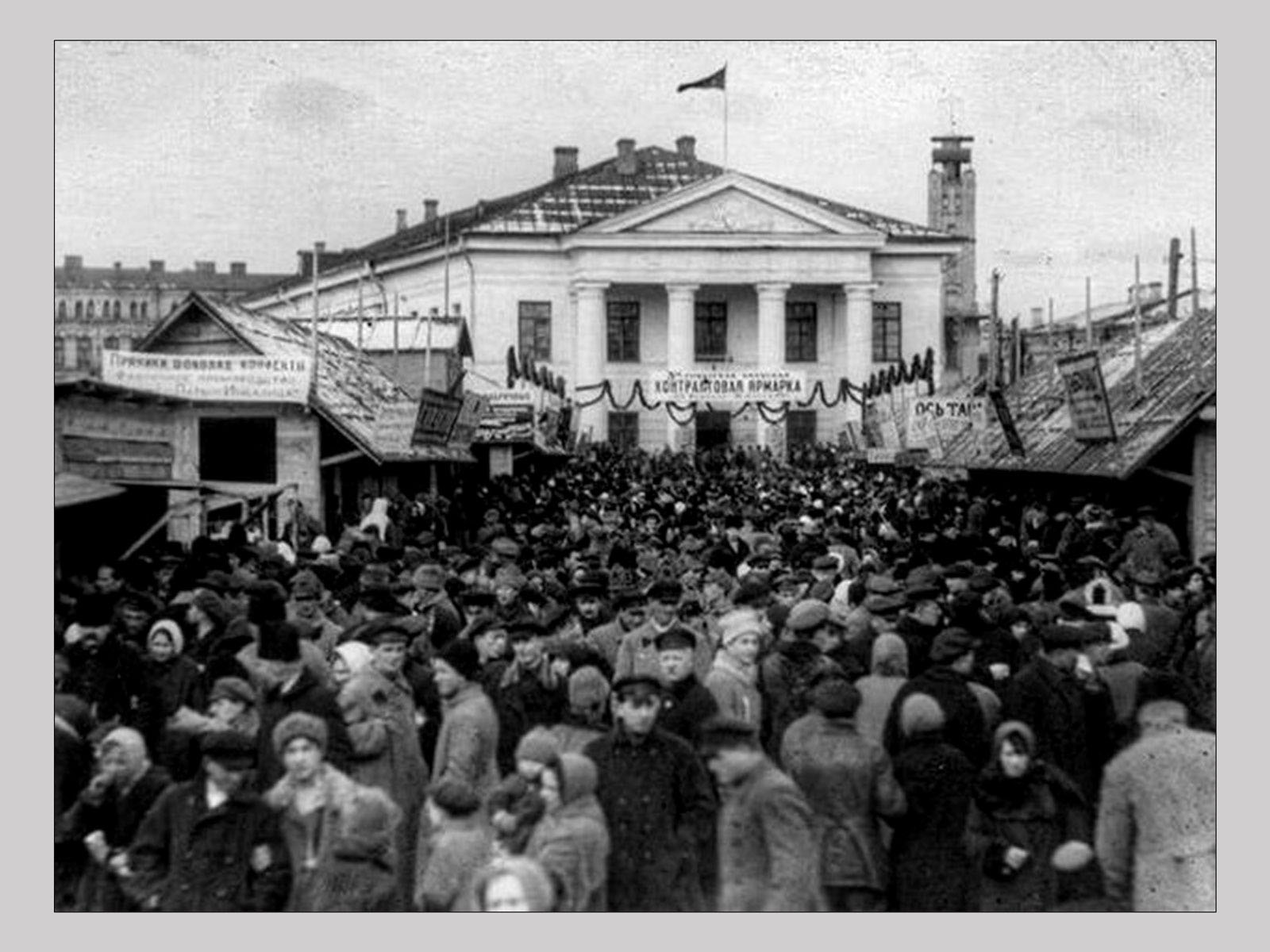

Restrictions on Jewish settlement in Kyiv

Some 4,500 Jews resided in the suburbs of Kyiv, including Demiivka, Solomianka, and Podil, in 1815. Nicholas I expelled Kyiv's Jews in 1835, likely in response to the demands from Kyiv's Christian merchants, unhappy with competition from Jewish traders. After that, Jewish merchants were permitted into the city for stays of only several days and were required to lodge in two Jewish inns leased out by the municipality. During the Contract Fair, however, they could enter the city freely.

Read more...

Alexander II's 1859 decree allowed only first-guild Jewish merchants to settle in the interior provinces and Kyiv; in 1861, second-guild merchants were also allowed. Later, artisans, post-service soldiers, and graduates of institutions were also allowed, though Jews continued to be restricted to specified neighbourhoods.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) II, 182;

- Natan M. Meir, Kiev, Jewish Metropolis: A History, 1859–1914 (Indiana University Press, 2010), 24.

1850s

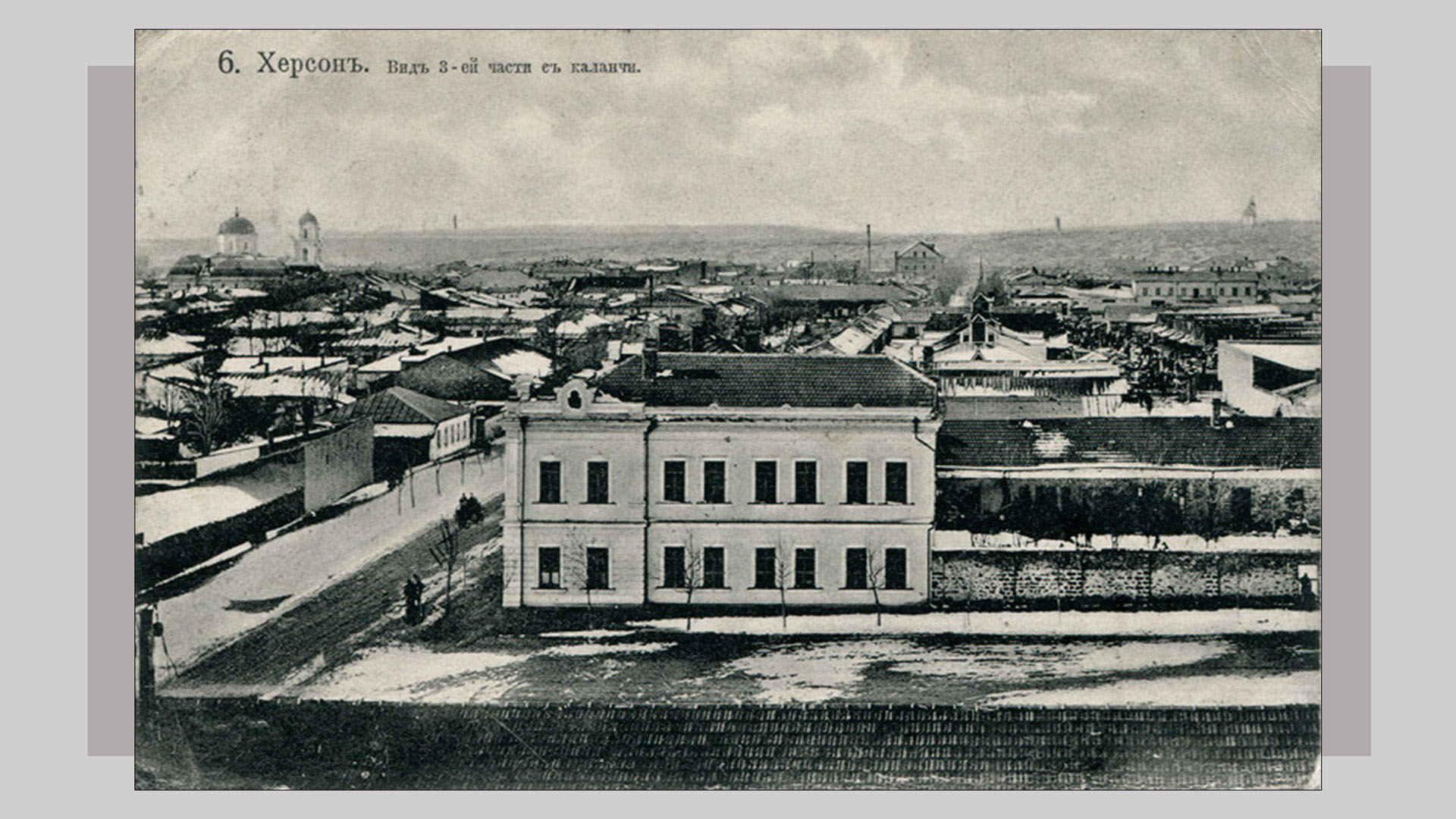

The Jewish population in the Russian Empire grew most rapidly in the provinces of Chernihiv, Kherson, and Poltava. These were the areas that benefitted from the expansion of the grain trade, where some Jewish agricultural settlement was possible, and where poorer parts of the population had a better chance to escape conscription.

sources

1860s–1913

Tsar Alexander II lifted certain restrictions on Jewish residence in the Russian Empire, permitting some Jews to live in parts of Kyiv and other previously restricted cities. These included important trading centres from which Jews had been excluded even though technically they were within the Pale.

Read more...

As only limited Jewish settlement was permitted in Kyiv, many Jews lived there illegally, setting the stage for frequent raids and forcible expulsions. The general climate in Kyiv was uncomfortable for Jews, which is why Sholem Aleichem, who lived in Kyiv, referred to the city in his stories as Yehupetz, probably a play on the Russian word for Egypt, Yegipt, in its Ukrainian pronunciation, Yehypet.

Nonetheless, the size of Kyiv's Jewish population grew considerably beyond official data, not taking into account persons with temporary resident status. Historians estimate that Kyiv’s Jewish population grew from about 3,000 in 1863 to 14,000 in 1872, reaching 32,000 in 1897 and 81,000 in 1913 (representing 13 percent of the total population).

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) I, 400, vol. II, 182;

- Natan Meir, "Kiev," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2011).

1872–1890s

There were 721,000 Jews living in the provinces of Kyiv, Volhynia, and Podolia in 1872, comprising 13 percent of the total population in the area. In the towns, they constituted 32 percent of the inhabitants, in some small towns, 53 percent, and in rural settlements, 14 percent.

Read more...

By the 1890s, nearly three-fifths (1.2 million) of the Jews in Dnieper Ukraine lived in the Right Bank provinces (Kyiv, Volhynia, and Podolia) due to the Russian government's residence restrictions. The vast majority of the Jews were concentrated in towns and cities. In three-fifths of those towns, they comprised about 40 percent of the population.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) I, 429;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 358.

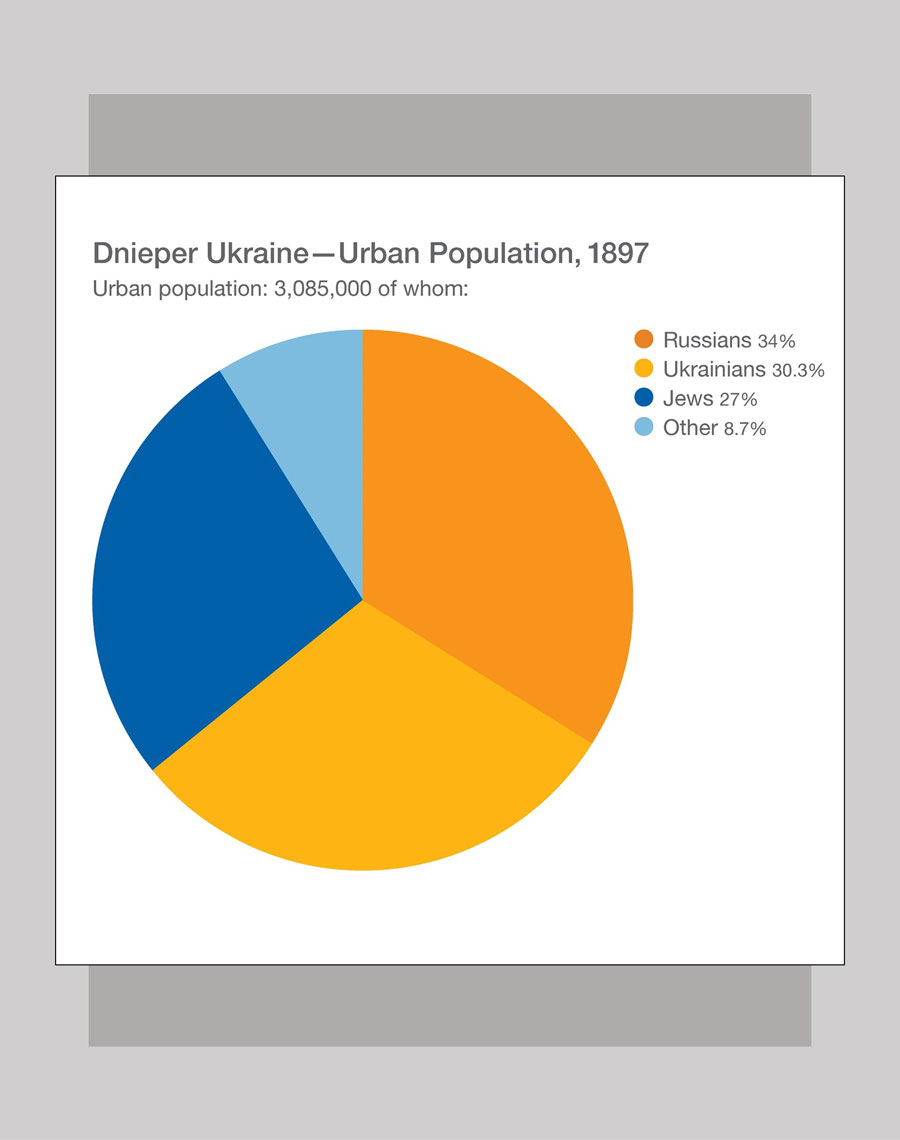

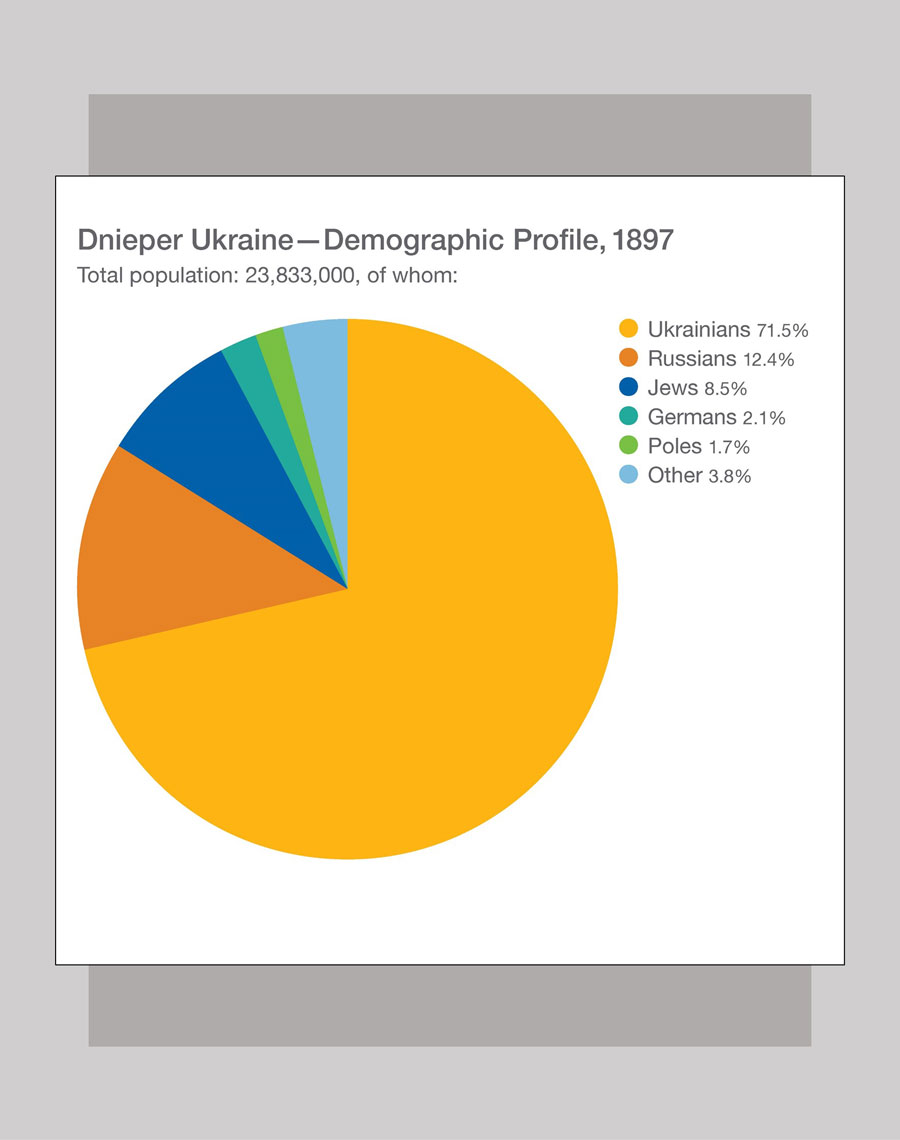

1897

The population census of 1897, the first and only universal census conducted in the Russian Empire, showedover two million Jews in Dnieper Ukraine, nearly three-fifths of whom (1.2 million) lived in the Right Bank. At the time, there were 5,198,401 Jews in the entire Russian Empire, a little more than 4 percent of the total population. Of Dnieper Ukraine's total population of 23,833,000, 71.5 percent were Ukrainians, 12.4 percent Russians, 8.5 percent Jews, 2.1 percent Germans, and 1.7 percent Poles.

Read more...

The last third of the nineteenth century saw dramatic growth in the overall urban population of Dnieper Ukraine and the proportion of Jews in urban centres in particular. Between 1863 and 1897, Dnieper Ukraine's urban population more than doubled, reaching over three million inhabitants living in 130 towns and cities. The five largest cities — Odesa, Kyiv, Kharkiv, Katerynoslav (Dnipro), and Mykolaiv — each at least tripled or quadrupled in size. According to the 1897 census, Dnieper Ukraine's total urban population was 3,085,000, of whom 34 percent were Russians, 30.3 percent Ukrainians, and 27 percent Jews.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 342, 350–351, 358;

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) II, 182;

- Michael Stanislawski, "Russia: Russian Empire," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

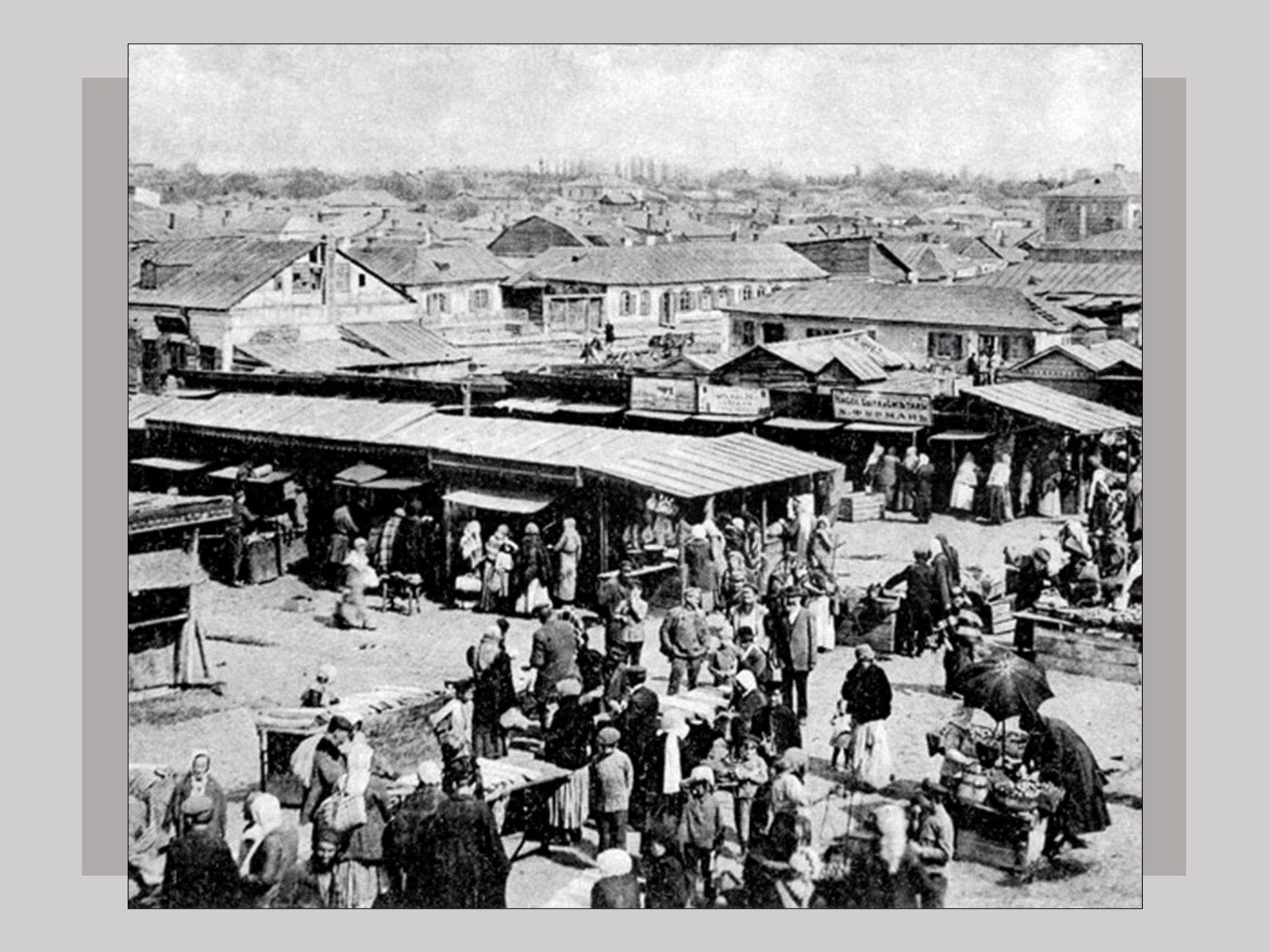

1900

The vast majority of Jews in Dnieper Ukraine lived in small towns and cities. In the Right Bank, 72 percent of Jews lived in towns with over 1,000 people; in three-fifths of those towns, they represented at least 40 percent of the population. In the Left Bank, 65 percent of Jews lived in towns with over 1,000 people, and in Steppe Ukraine, 65 percent. Among larger towns and cities, those with the largest percentage of Jewish inhabitants in 1900 were Berdychiv (78 percent), Uman (59 percent), Balta (57 percent), Rivne (56 percent), Mohyliv-Podilskyi (55 percent), Proskuriv (50 percent), Kamianets-Podilskyi (49 percent), Zhytomyr (47 percent), Vinnytsia (38 percent), and Odesa (34 percent). Of Kyiv's total population of 248,000, Russians and Russified Ukrainians constituted 52.9 percent, Ukrainians 22.1 percent, and Jews 13 percent. In Dnieper Ukraine as a whole, 26 percent of all Jews lived in twenty cities, each of which had over 10,000 Jews.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 358;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Ukraine: An Illustrated History (Toronto, 2007), 162.

1903–1904

Vyacheslav Plehve, the Minister of the Interior, who had in 1890 drafted a proposal for imposing more severe restrictions on Jews, later lifted restrictions on where Jews could reside. While prohibiting Jews from acquiring land outside the towns of the interior, he allowed Jewish settlement in over a hundred and fifty localities in the Pale, classed as towns. He also halted the expulsions of Jews from localities where they could not reside legally and rescinded the prohibition on Jewish residence within 30 miles of the western border.

sources

1911–1913

Although the vast majority of Jews resided in cities and towns, the tsarist government encouraged their resettlement in agricultural colonies in rural areas in the southern steppe of Ukraine. By 1913, over 42,000 Jews resided in 38 rural communities, mainly in Kherson and Katerynoslav provinces. These Jewish communities were largely destroyed in the anti-Jewish violence of 1919–20.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Ukraine: An Illustrated History (Toronto, Second Edition, 2007), 233.

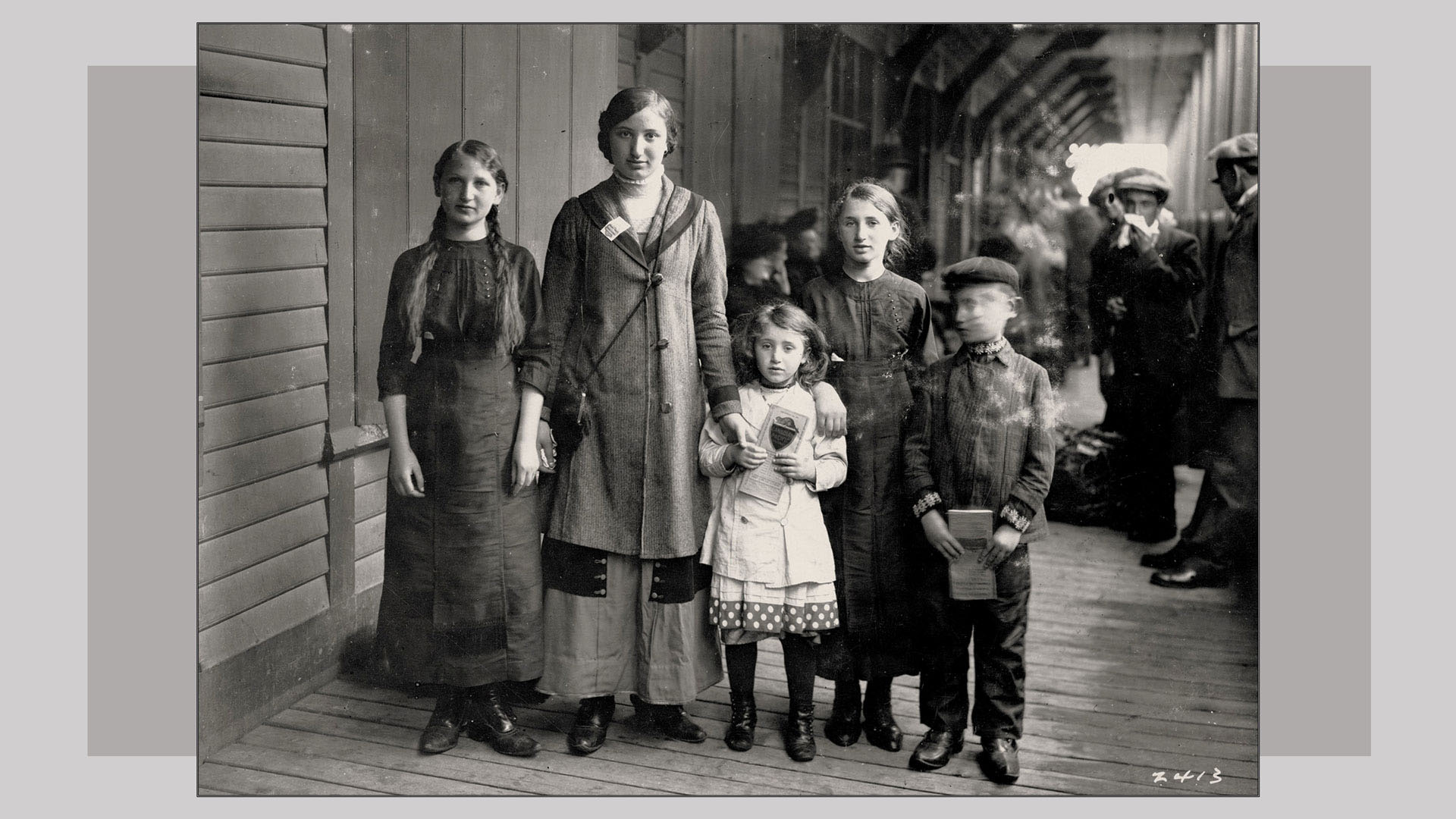

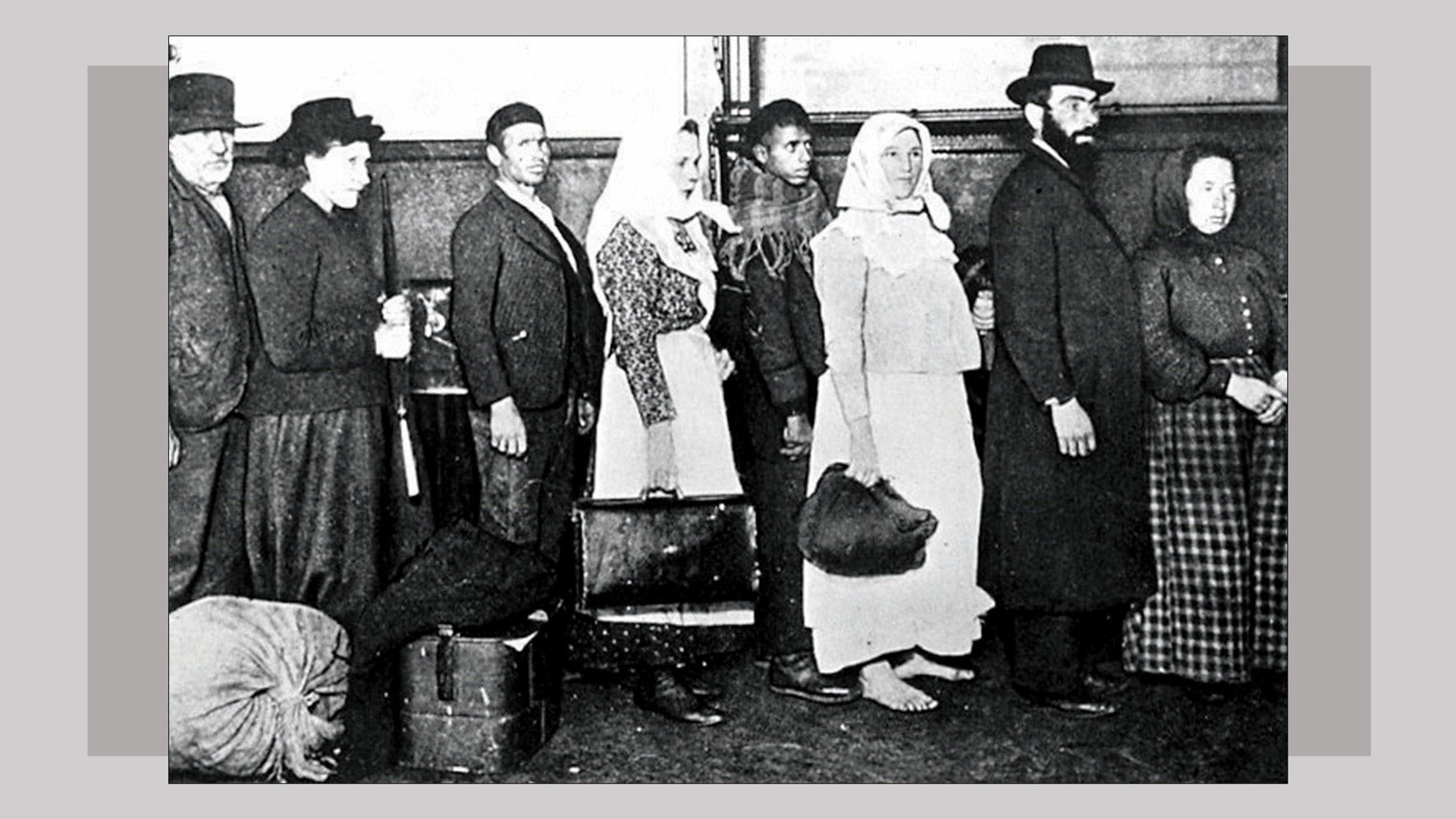

1880s–1914

Emigration

Jews and Ukrainians began to emigrate in large numbers from both tsarist Russia and Habsburg-ruled lands. Ukrainian peasantry, motivated primarily by the decreasing availability of land, emigrated from Austria-Hungary mainly to the United States and Canada, and from Russian-ruled Ukraine mainly to the North Caucasus and the Russian Far East. Many Jewish emigrants were motivated by a desire to escape poverty; they were also affected by the pogroms of the early 1880s, and especially by the more widespread and deadly pogroms that occurred in tsarist Russia in 1903–1906.

Read more...

More than two million Jews migrated to North America from Eastern Europe during this period, mainly from Ukrainian lands — about 1.6 million from the Russian Empire (including Poland). Between 1894 and 1914, Jews made up as much as 59 percent of all immigrants from the Russian Empire to the United States. Other destinations included Canada, Western Europe, Palestine, Latin America, and southern Africa. However, the mass emigration accounted for only one-third of the Jewish population of the Russian Empire — two-thirds of Russian Jews did not emigrate. The Jewish immigrants in North America and elsewhere soon established religious and communal organizations, including Landsmanschaft societies, that brought together immigrants from specific towns or regions in the old country.

By 1914, some 600,000 Ukrainian immigrants, almost all from Austrian-ruled Ukrainian lands, emigrated to the United States and Canada, mainly to the Prairie provinces. Determined to maintain their Ukrainian heritage, they established distinct community structures in North America, including a range of secular and religious, cultural, and benevolent organizations.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 363, 458–459;

- Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe (New York, 2015), 362;

- Michael Stanislawski, "Russia: Russian Empire," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).