1858

In one of the first public protests against antisemitism in the Russian Empire, an open letter, signed by 140 prominent personalities, was published in Russkii vestnik (Russian Herald) in defence of two Jewish publicists libelled in an anonymous column in the St. Petersburg journal Illiustratsiia. Signatories to the letter included historian and publicist Mykola Kostomarov and celebrated Ukrainian writers Taras Shevchenko and Marko Vovchok (pen name of Mariia Vilinska). Symptomatic of the time, however, the letter drafted by Panteleimon Kulish itself contained embedded stereotypes about both Jews and Ukrainians. It asserted that Jews "became, and could not help but become, sworn enemies of people of other religions who heaped abuse on their [Jewish] faith…. Hampered everywhere by the laws themselves, the Jews unwillingly turned to slyness and trickery…." Perhaps in a well-meaning but still stereotypical vein, the letter added that "only education and equality of civil rights can cleanse the Jewish nation of all that is hostile in it to the people of other faiths."

Read more...

The letter also stated how remarkable it was that eminent Ukrainians protested Illiustratsiia's defamatory characterization of Jews because the Ukrainian nation "more than the Great Russians and the Poles has suffered from the Jews and in days gone by expressed its hatred toward the Jews in thousands of bloody victims... [that they] avenged themselves on the Jews with such simple-hearted conviction of the justice of blood-letting that they even glorified their terrible feats in their genuinely poetic songs."

Ironically, as both the celebrated Ukrainian writer Ivan Franko and the eminent Ukrainian historian Mykhailo Hrushevsky noted, Kulish himself was responsible for propagating anti-Jewish motifs by altering the text of traditional poetic ballads (dumy), which in turn conveyed such motifs to nineteenth-century Ukrainian literature.

sources and related

- Myroslav Shkandrij, Jews in Ukrainian Literature. Representation and Identity (New Haven, 2009), 16–17, 20–22;

- George G. Grabowicz, "The Jewish Theme in Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Ukrainian Literature," in Peter Potichnyj, Howard Aster, eds. Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective (Edmonton, 1988), 333–334.

Related

Chapter 6.4 1890s–1900s (Ukrainian ethnography)

Chapter 6.5 1862 (Mykola Kostomarov)

Chapter 6.5 1876–1883

1861–1862

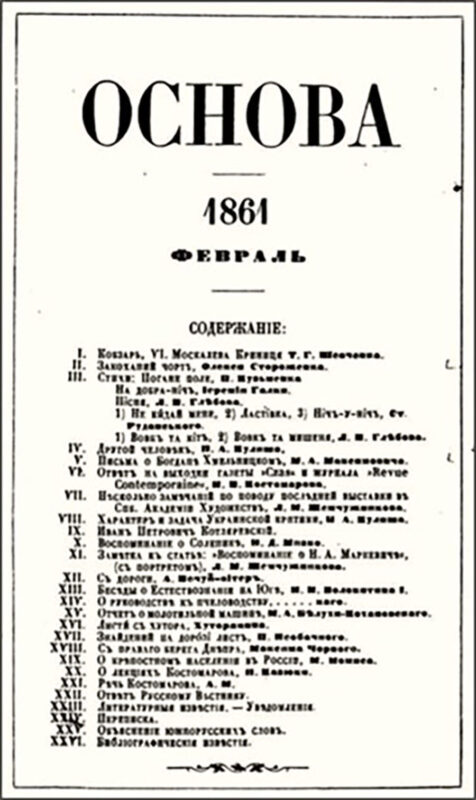

The first public debate in modern times on Ukrainian-Jewish relations took place on the pages of Sion, the Russian-language Jewish journal published in Odesa, and the Ukrainian publication Osnova, a progressive journal and the only legal organ of Ukrainophiles in the Russian empire. Veniamin Portugalov, a Jewish activist from Poltava province, initiated the debate when he came across the word zhid in Osnova. In Russian usage, the term zhid/zhyd ("Yid") was regarded as derogatory, the preferred neutral term being evrei.

Osnova's editor Panteleimon Kulish responded that the term zhid/zhyd in Ukrainian is sanctioned by long usage and is not pejorative. He then added that the real obstacle in Jewish-Ukrainian relations was the voluntary isolation of Jews from the Ukrainian population — a theme Kulish elaborated in immoderate language in articles published in Osnova, explaining why there was mutual antagonism between Jews and Ukrainians.

Read more...

Osnova responded, willing to accept zhid/zhyd as a legitimate designation for a Jew. However, as stated by historian Roman Serbyn, Sion rebuffed Osnova's complaint regarding "the lack of Jewish integration into the Ukrainian community with the counter-proposition that Ukrainians were pursuing their own narrow, 'exclusivist national' interests."

According to literary historian Myroslav Shkandrij, underlying the debate was the aspiration of the Jewish intelligentsia "to overcome linguistic, cultural, and territorial isolation through integration into the whole Russian Empire" and its perception of Ukrainian particularism as a threat to such integration. In contrast, the Ukrainian intelligentsia perceived the gravitation of Jews to the Russian language and culture as advancing Russification and in tension with their own drive for Ukrainian national and cultural emancipation.

sources

- Roman Serbyn, "The Sion-Osnova Controversy of 1861–1862," in Peter Potichnyj, Howard Aster, eds. Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective (Edmonton, 1988), 85, 91–93;

- Myroslav Shkandrij, Jews in Ukrainian Literature. Representation and Identity (New Haven, 2009), 35–38.

1875–1883

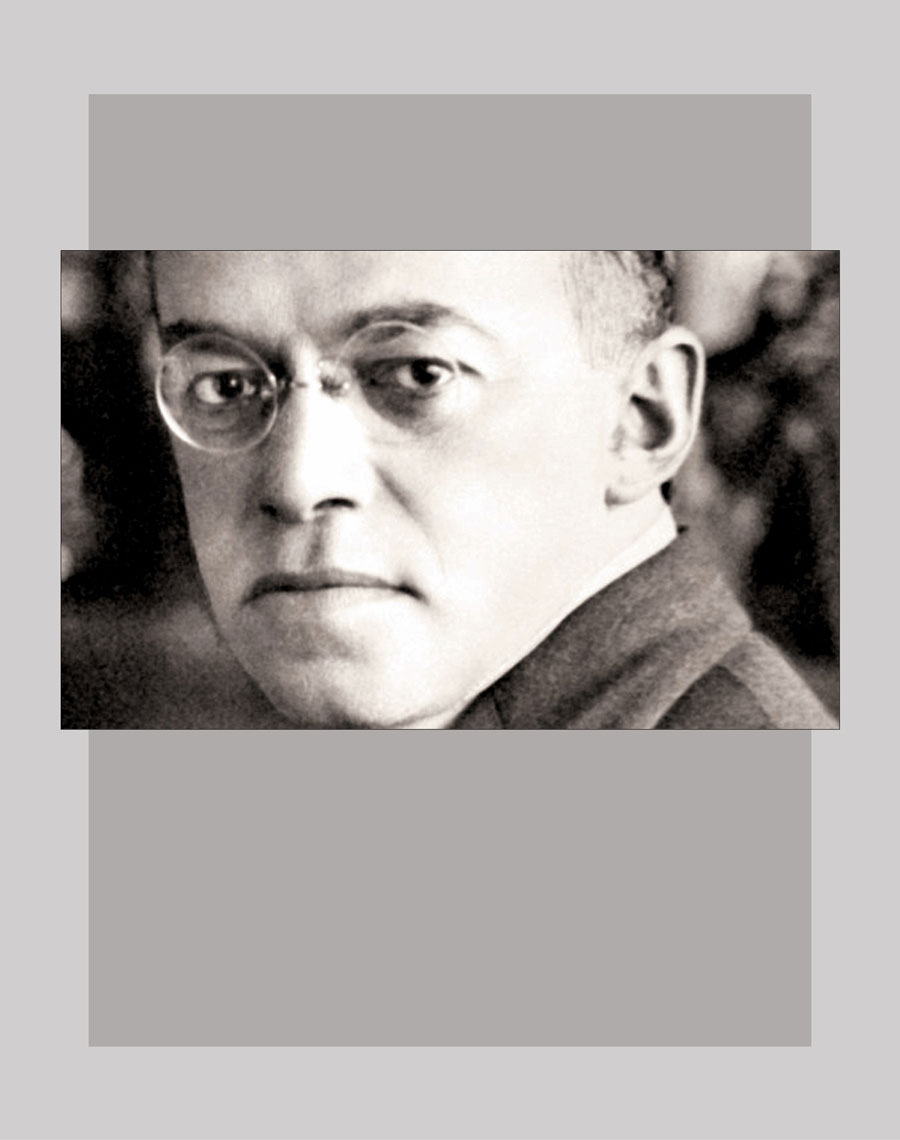

Mykhailo Drahomanov, an influential figure in formulating the Ukrainian national movement's stance on 'the Jewish question,' published his article "Jews and Poles in the South-Western Land" (1875). In this article, he argued that the Jews represent a "parasitic class" in relation to the Ukrainian peasantry as the majority of Jews were petty tradesmen, innkeepers, and middlemen. In later articles published in Geneva (1881–1883), he reiterated the view that the majority of Jews were part of the capitalist system that exploited the masses — that "the Jewish nation (natsiia) is not only largely composed of one estate (soslovie), but that this estate is parasitic."

Drahomanov later qualified this harsh judgment by noting that one-third of Jews in Ukrainian lands were workingmen, and most were very poor. His proposed solution was a socioeconomic restructuring of both the Jewish community and Ukrainian society. His emphasis on social solidarity above national solidarity enabled him to appeal to Ukrainian radicals to nurture "goodwill toward working Jews."

Read more...

At the same time, he considered Jews a distinct nation and was among the first Ukrainian intellectuals to propose that Jews be granted civil rights and national autonomy, protected by constitutional guarantees — though neglecting to acknowledge Judaism as a foundation of Jewish self-identity.

sources

- Moshe Mishkinsky, "The Attitudes of the Ukrainian Socialists to Jewish Problems in the 1870s," in Peter Potichnyj, Howard Aster, eds. Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective (Edmonton, 1988), 57, 61, 68;

- Myroslav Shkandrij, Jews in Ukrainian Literature. Representation and Identity (New Haven, 2009), 51;

- Yaroslav Hrytsak, Ivan Franko and His Community (Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, 2018), 317.

1900–1906

The Revolutionary Ukrainian Party (RUP), the first Ukrainian political party in the Russian Empire, and the splinter groups that emerged from it developed differing agendas in relation to Jews. The RUP, created in Kharkiv by a group of students, sought to merge socialist and Ukrainian nationalist ideas to reach out to the peasantry and rural proletariat. Its initial program, elaborated in a pamphlet written in 1900 by Kharkiv lawyer Mykola Mikhnovsky, clearly stated that RUP's goal was Ukrainian independence. By 1902, however, most RUP members sought autonomy in a democratic federal Russia, not outright independence.

Read more...

Mikhnovsky then organized the clandestine Ukrainian People's Party (UPP), re-asserting commitment to an independent Ukrainian state. Another splinter group, Spilka (Union), formed in December 1904, was multiethnic in composition and had close ties to the Russian Social Democrats and the Jewish Bund. Spilka opted for national-territorial autonomy for Ukraine within a federated, democratic Russia.

The RUP founder, Dmytro Antonovych, promoted stronger formal ties with the Jewish socialist party, the Bund. Under his leadership, the RUP issued proclamations and published articles in its periodicals highlighting the Russian government's persecution of the Jews in Ukraine and showing how the overwhelming majority of the Jewish population lived in poverty and therefore could not be considered an exploiting nation. As described by Volodymyr Doroshenko, a member of the RUP: "The struggle for national self-expression and political freedom united the Jewish and Ukrainian youth in the gymnasiums, the university, and beyond the lecture rooms. Such unity was manifest in Poltava, Lubny, Pryluky, Nizhyn, and Kyiv, which I know from personal experience."

In contrast, the UPP, led by Mikhnovsky, preached exclusion of 'foreigners,' including Jews, from Ukrainian society. Its platform stood for a "free, independent, democratic Ukraine without lord and slave" and "free of foreigners." The UPP's pamphlet, The Ten Commandments of the UPP, explained to Ukrainians that "all peoples are your brothers, but the Russians, Poles, Hungarians, Romanians, and Jews — these are the enemies of our nation as long as they rule over us and exploit us."

sources

- Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe (New York, 2015), 192–193;

- Arkadii Zhukovsky, "Revolutionary Ukrainian party" and Roman Senkus, "Ukrainian Social Democratic Spilka," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1993);

- Yury Boshyk, "Between Socialism and Nationalism: Jewish-Ukrainian Political Relations in Imperial Russia, 1900–1917," in Peter Potichnyj, Howard Aster, eds. Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective (Edmonton, 1988), 176–177, 181.

1905–1907

Two Ukrainian-language dramas, published in 1906, treated the theme of Ukrainian-Jewish relations in the context of the pogroms current at the time: Lykholittia (Hard Times) by Hnat Khotkevych and Dysharmoniia (Disharmony) by Volodymyr Vynnychenko. The two playwrights were representative of the generation of modernists who implicitly endorsed religious tolerance and equality before the law, affirmed solidarity between Jews and Ukrainians against the same oppressive system, and expressed commitment to revolutionary change.

Read more...

While both works delve into the psychology and organizational methods of the notorious Black Hundreds, they differ in their understanding of recent events. For Khotkevych, the pogroms and the failed 1905 revolution were a political setback and a great human tragedy, made additionally meaningful (as observed by George Grabowicz) as "a noble legacy of common effort and common martyrdom." Vynnychenko's stance was more pessimistic. While demonstrating how the pogromists were manipulated, provoked, and sometimes paid by the pro-government forces to use violence, Vynnychenko also drew attention to antisemitism among the revolutionaries themselves. As observed by Myroslav Shkandrij, Vynnychenko was struck by their political naiveté — "their innocent faith in universal brotherhood and democratic liberties" and their tendency to underestimate "not only the importance of the national question, but also the ugly reality of racial, social, and political prejudices."

sources

- Myroslav Shkandrij, Jews in Ukrainian Literature. Representation and Identity (New Haven, 2009), 83–85, 88–89;

- Mykola Iv. Soroka, "Jewish Themes in Volodymyr Vynnychenko's Writing," in Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern and Antony Polonsky, Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry, Volume 26, Jews and Ukrainians, (Oxford, 2014), 215–217;

- George G. Grabowicz, "The Jewish Theme in Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Ukrainian Literature," in Peter Potichnyj, Howard Aster, eds. Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective (Edmonton, 1988), 340–341.

1907

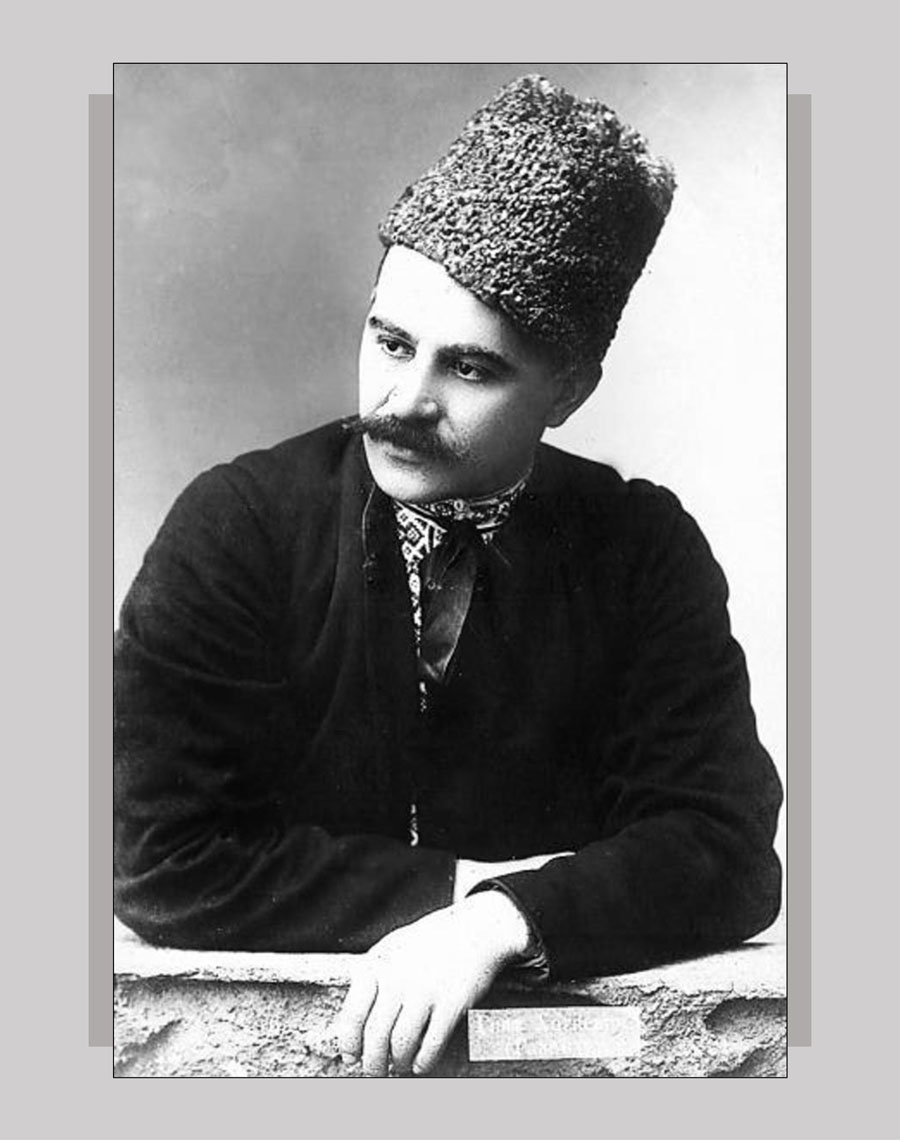

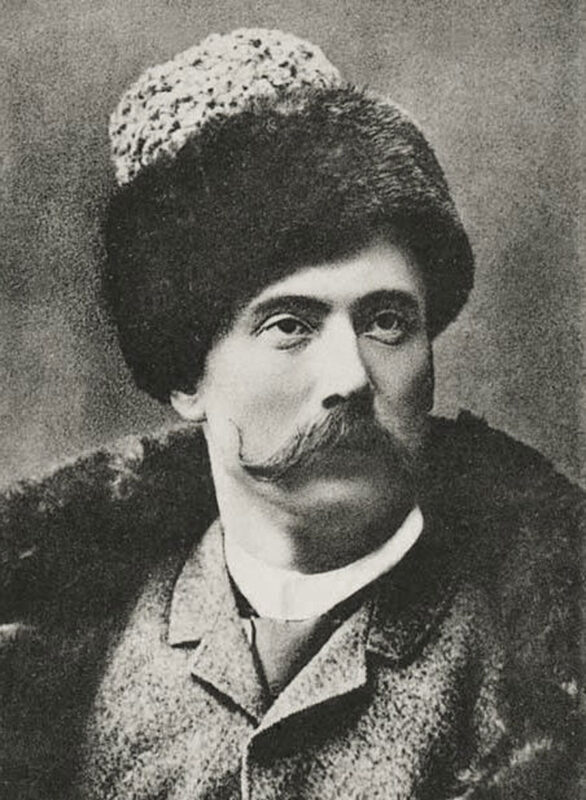

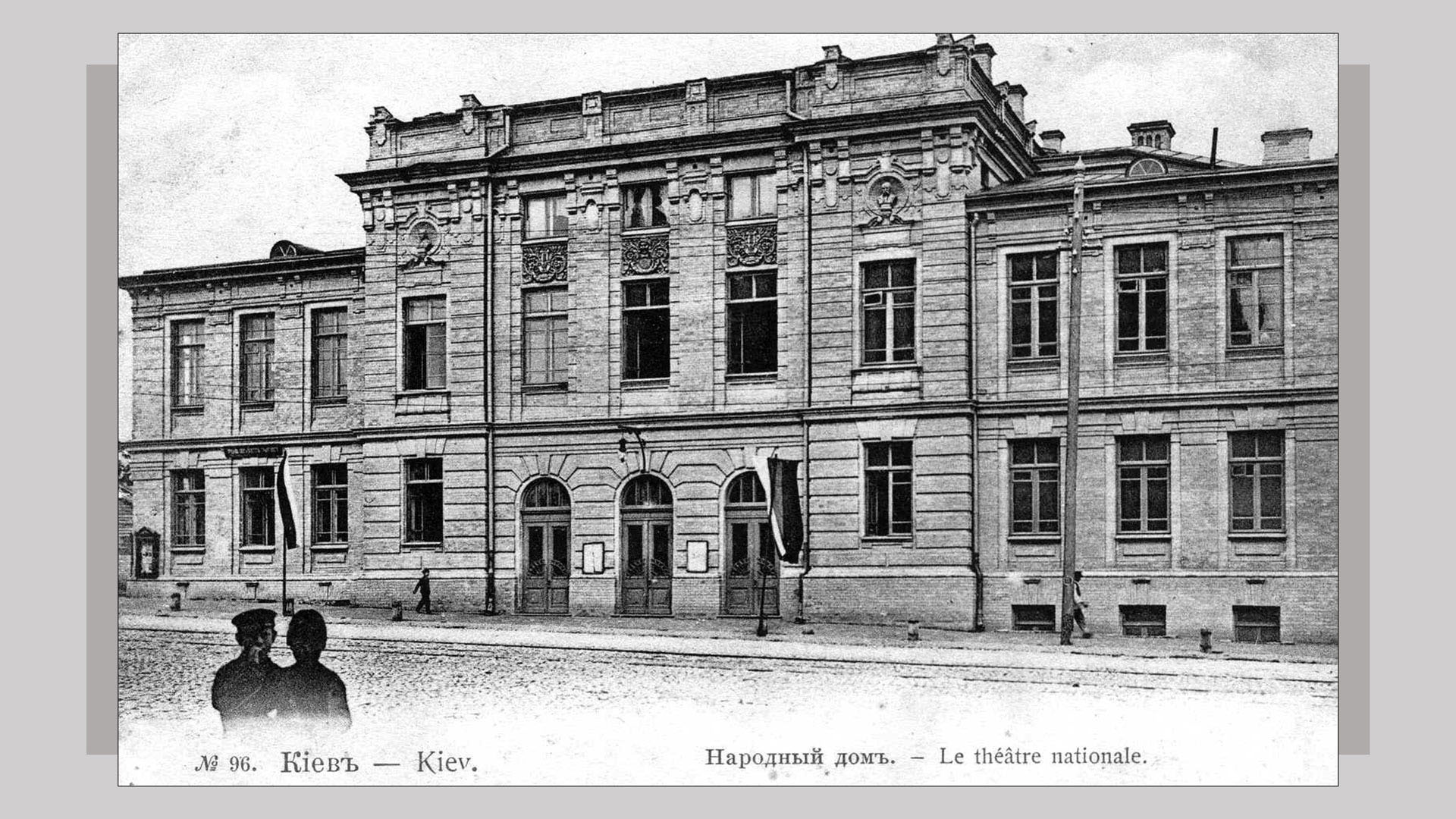

After the draconian restrictions imposed by the 1876 Ems Ukase (decree) were lifted in 1905, Mykola Sadovsky established the first permanent Ukrainian theatre in Kyiv. His theatre was especially successful in producing Ukrainian historical dramas, such as Mykhailo Starytsky's Bohdan Khmelnytsky, and staging Ukrainian operas. From the start, Sadovsky's theatre included in its repertoire plays by Jewish playwrights, such as Avram Goldfaden, Sholem Asch, and Jacob Gordin, and employed many Jewish musicians — thereby attracting audiences from Kyiv's growing Jewish population.

Read more...

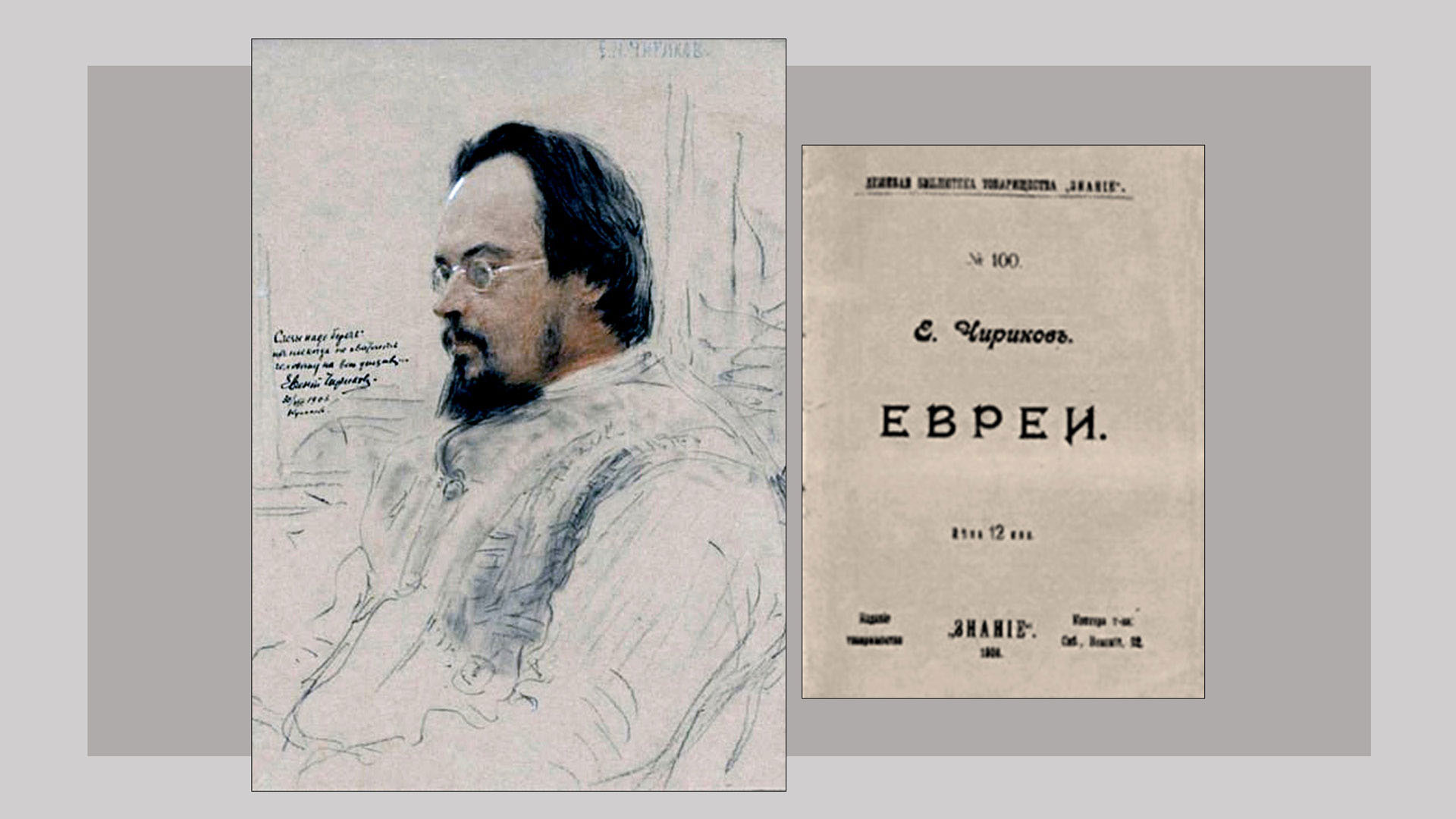

For the theatre opening, Sadovsky had planned to stage a Ukrainian translation of the 1903 play Evrei (Jews) by Russian writer Evgenii Chirikov. However, the police banned the play because it seemed to be targeting the autocratic tsarist regime. The play, a response to the 1905 pogroms, was performed in the following season. Interestingly, the Ukrainian translation of Evrei (published in 1907) included a foreword by the journalist (later Ukrainian political leader) Symon Petliura, in which he wrote: "The suffering of Nachman in Chirikov's Evreiwill evoke profound sympathy in everyone, regardless of whether they belong to this nation whose historical destiny has been to carry the heavy cross of oppression and violence." During this period, Petliura edited the Kyivan newspaper Slovo (The Word), which exposed the antisemitic views of some writers published in the newspapers Rada (The Council) and Ridnyi krai (The Native Land).

sources

- Myroslav Shkandrij, Jews in Ukrainian Literature: Representation and Identity (New Haven & London, 2009), 60–64;

- Myroslav Shkandrij, “There are problems in Ukraine that are challenging historians, writers, and civil society,” Hadashot, English translation on UJE website, 18 December 2019;

- Nikolayev, Bibliographic Dictionary of Russian Writers, Vol. 2 (lib.ru., 1990, Russian).

1906–1908

In the wake of the 1905 Russian revolution, Ukrainian and Jewish political parties in the Russian Empire developed close cooperation in both official and underground political activity. During the elections to the First and Second State Duma (1906–1907), the influential Ukrainian Democratic Party formed electoral blocks with Jewish organizations and parties, such as the Union for Attainment of Equal Rights for the Jews and Zionists (Union for Jewish Equality). The liberal Constitutional Democratic (Kadet) Party (Konstitutsionno-Demokraticheskaya Partiya, K-D) advocated for a constitutional monarchy and full citizenship for all Russia's minorities, including recognition of the right of the non-Russian peoples to develop their national cultures. This party drew significant support from both Jews and Ukrainians and won one-third of the seats in the First Russian Duma. In 1908, following the tsarist government's purges of Ukrainian nationalist organizations and parties, Jewish and Ukrainian parties cooperated in smuggling wanted men and women out of Russia. The Jewish Bund (The Union of Jewish Workers in Lithuania, Poland and Russia) helped Symon Petliura and other Ukrainian social democrats escape to Lviv in Austrian Galicia.

sources

- Yury Boshyk, "Between Socialism and Nationalism: Jewish-Ukrainian Political Relations in Imperial Russia, 1900–1917," in Peter Potichnyj, Howard Aster, eds. Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective (Edmonton, 1988), 184–185;

- Hans Rogger, Jewish Policies and Right-wing Politics in Imperial Russia (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1996), 20.

1908–1911

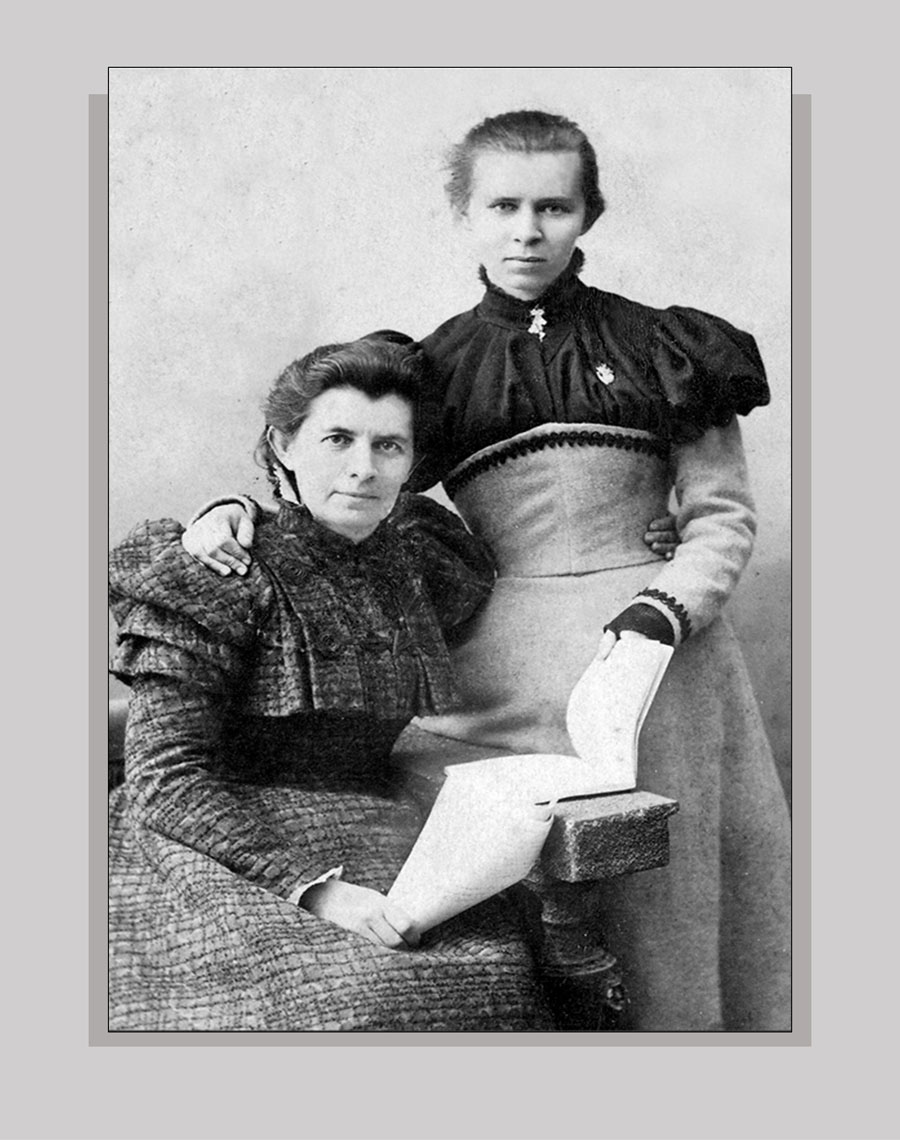

Olena Pchilka, the prominent Ukrainian writer and nationalist, published an article, "Nasha sprava s zhydamy" (Our Case with Jews), in the Ukrainian-language periodical Ridnyi krai, of which she was the editor. She used this platform to complain about the "progressive" Jewish intelligentsia that hindered Ukrainian cultural and national strivings by always choosing to join the ranks of the "ruling nations" — such as Russians, Germans, or Poles. Some members of the Ukrainian intelligentsia regarded this view as chauvinistic.

In 1911, as if responding to Pchilka, the prominent Zionist leader Vladimir Jabotinsky, writing to Ukrainian newspaper editors in Kyiv, argued that Ukrainian nationalists and Zionists had identical enemies and goals; and that national schools and the fight against Russifiers and Polonizers were issues on the agendas of both nations. Jabotinsky went on to promise that the Zionist press would show the Jews "that they must turn their attention toward Ukrainians and not be Russifiers."

Read more...

Jabotinsky later believed that Jews had to form a state of their own because their integration into non-Jewish society was impossible. In his view, the major obstacle to integration was the unavoidable "antisemitism of things," inherent in the inevitable economic conflict caused by the competition between Jewish middlemen and the rising middle class of nations, such as Poles and Ukrainians.

sources

- Yury Boshyk, "Between Socialism and Nationalism: Jewish-Ukrainian Political Relations in Imperial Russia, 1900–1917" and Martha Bohachevsky-Chomiak, "Jewish and Ukrainian Women," in Peter Potichnyj, Howard Aster, eds. Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective (Edmonton, 1988), 186–8, 365;

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. II, 23.

1910–1912

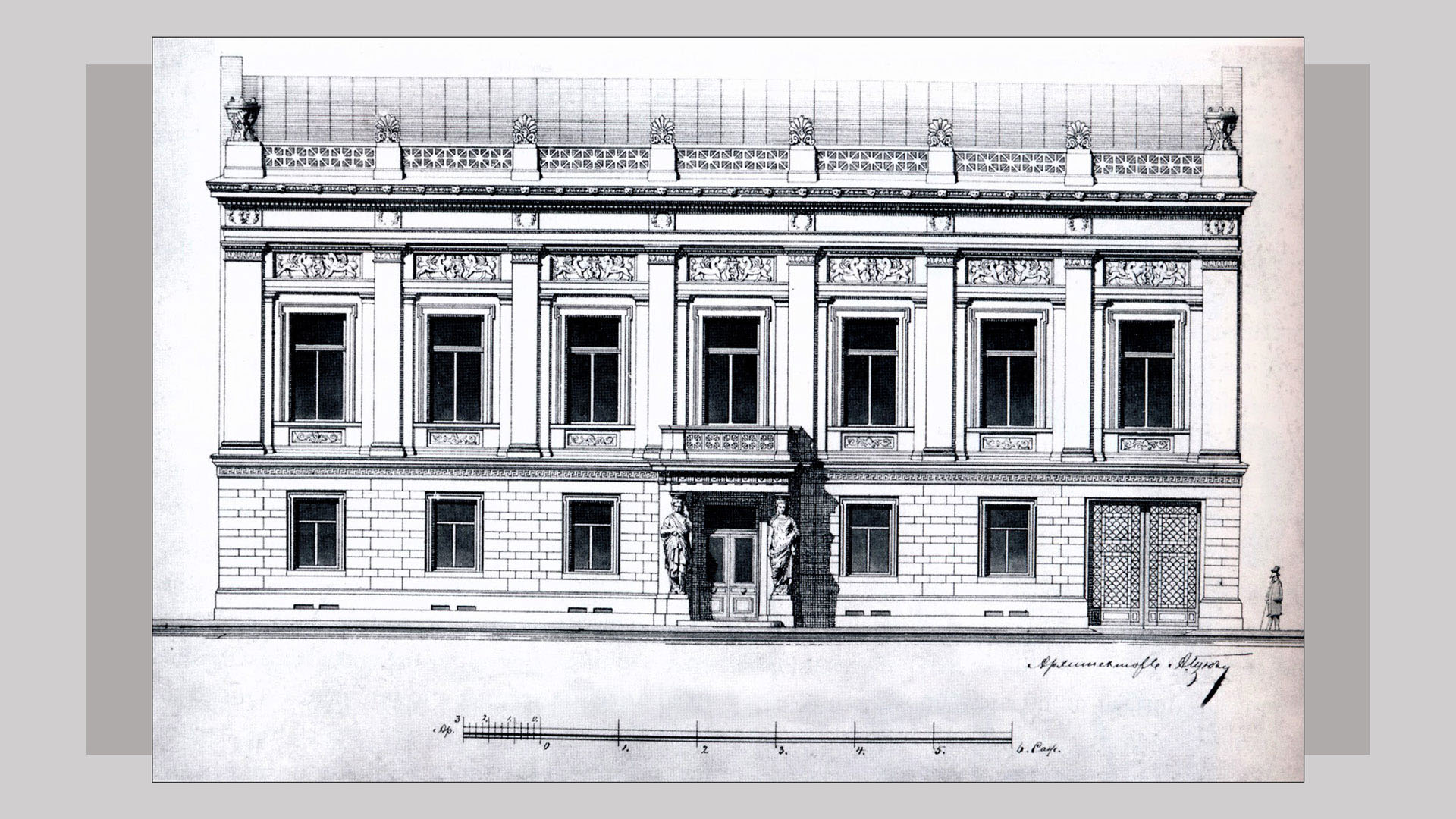

In Kyiv, the close working relationship between the Jewish Brodsky family and the Ukrainian Tereshchenko family in the sugar-refining industry also extended to their philanthropy. Both families sponsored major philanthropic projects in Kyiv, which benefited both Jewish and non-Jewish cultural and welfare institutions and the wider public. In addition to dignified synagogues, the Brodskys helped fund a hospital, a bacteriological institute, and a polytechnic institute. In his will, Lazar Brodsky bequeathed funds for the construction in Kyiv of the Besarabsky Covered Market (still in use today) on the condition that the income from the market would be used to support his favourite charities. The Tereshchenkos gave Ukraine numerous stately buildings, support for cultural and educational institutions, and art collections now kept in the Kyiv museums they helped establish. They were also among the few Christian families who supported Jewish causes.

sources

- Natan Meir, Kiev: Jewish Metropolis (Bloomington and Indianapolis, 2010), 195–196;

- Natan Meir, "Brodskii Family," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010);

- Oleksandr Surhay, "Oleksandr Tereshchenko: Founder of Kyiv's Educational Institutions," Den (6 June 2000);

- Arkadii Zhukovsky, "Tereshchenko," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1993).