1340s–1500s

Grand Duchy of Lithuania

While Poland was consolidating its rule over Galicia, the other half of the Rus' kingdom, Volhynia, was conquered by Lithuania (1340s). Within the next two decades, the Lithuanians successfully challenged the Golden Horde (1362) and incorporated not only the former principalities of Kyivan Rus' but also the steppe lands, eventually reaching the shores of the Black Sea. Most of the Ukrainian lands then became part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Power struggles in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, coinciding with a royal succession crisis in Poland in the 1380s, were resolved by the marriage of Lithuanian Prince Jogaila/Jagiełło and Polish Queen Jadwiga. The marriage initiated the gradual unification of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the conversion of Jagiełło and most of the Lithuanian elite from paganism or Eastern Orthodoxy to Roman Catholicism. In addition, Jagiełło had to agree to meet the demands of Poland's nobles to respect their existing privileges (such as exemption from taxes and the exclusive right to hold key administrative positions in the various provinces).

Read more...

With Jadwiga's untimely death (1399), the dynastic connection between Lithuania and Poland was interrupted but restored when Jagiełło's son by a later marriage, Casimir IV, was chosen by Lithuanian boyars to be Grand Duke (r. 1440–1492) and then became King of Poland (r. 1447–1492). In the following decades, the Polish palatinate administrative structure, which had already been established in Galicia by 1440, was gradually introduced also in the Rus’-inhabited lands of Kyiv (1471), Volhynia (1566), and Bratslav (1566).

In these lands, nobles of the Catholic faith were favoured in significant ways over Eastern Orthodox Rus' nobles; but the latter rebelled (1430–1434) and won full political rights. In contrast, Orthodox Rus' leaders in Galicia experienced a continual decline in status under Polish rule. Previously politically powerful Orthodox boyars were forced to leave the area and were replaced by Polish officials, while gentry of the Catholic faith received large tracts of land. The Rus' leaders responded by forming alliances with Orthodox Moldavian leaders (1457–1504) and staging a rebellion. The rebellion (1490–1492), organized by local leader Petro Mukha, engaged nearly 10,000 Moldavian and Rus' peasants, as well as petty nobles and townspeople, in an unsuccessful attempt to overthrow Polish rule in southern Galicia.

In the mid-1500s, Muscovy's rulers began to act on their claim that they were the descendants of Riuryk, the declared founder of Kyivan Rus', and therefore the legitimate heirs of the territory of Kyivan Rus'. The threat from Muscovy and the acquisition by Ivan IV ("the Dread," r. 1547–1584) of several borderland strongholds from Lithuania (including Chernihiv) led to the second stage of Lithuania's increasingly closer association with Poland.

sources and related

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Ukraine: An Illustrated History (Toronto, Second Edition, 2007), 57, 63–64, 157;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 136–140;

- Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe (New York, 2015), 359;

- "Mukha rebellion," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1993).

Related

Chapter 3.4 1370s–1430s

1507

The Lithuanian Grand Duke and Polish King Zygmunt I granted the Jews a charter of protection, which gave Jews the right to practise their religion, exemption from the jurisdiction of municipal authorities, and security measures against physical attack. To enhance the importance and antiquity of the document, the charter was backdated to 1388 and attributed to Grand Duke Vytautus/Vitold (r. 1392–1430), the first Catholic ruler of Lithuania.

The charter sheds light on the status of Jews in the hierarchical corporate structure of European medieval feudal society. It also illustrates how the tenth-century Magdeburg Law (relating to town privileges) was implemented in many Eastern and Central European municipalities.

sources

- Omeljan Pritsak, "The Pre-Ashkenazic Jews of Eastern Europe in Relation to the Khazars, the Rus' and the Lithuanians," in Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective, Peter Potichnyj & Howard Aster, eds. (Edmonton, 1988), 16–17.

1539

Legislation was passed giving owners of private towns (more than half of the realm's towns) exclusive jurisdiction over their Jewish communities. This arrangement was at the origin of the peculiar marriage of convenience between Jews and the nobility, as the nobles engaged the services of Jews in managing their estates, and Jews depended on the nobility for protection and their livelihood. As observed by the chancellor to Zygmunt I, "there is hardly a magnate who does not hand over the management of his estates to a Jew, and more zealously protects them against any wrong, real or imaginary, than he protects Christians." The taxation system, lease-holding (arenda) system, and alcohol monopolies connected with this arrangement fueled enduring intergroup tensions and episodes of violence.

sources and related

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford and Portland, OR, 2010), vol. I, 35.

Related

Chapter 4.3 1569–1600s

1449–1783

The Crimean Khanate

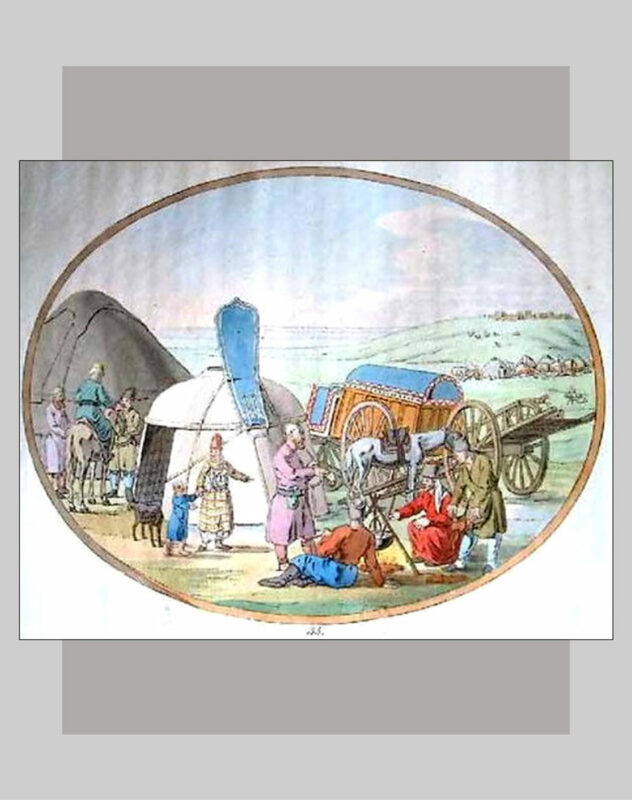

Successors of the Mongol Golden Horde formed their own Khanate along the northern coast of the Black Sea in the Crimean Peninsula and the southern Ukrainian steppes. The Crimean Khanate became a protectorate of the Ottoman Empire in 1475, after the conqueror of Constantinople, Sultan Mehmed II (r. 1451–1481), drove out the Genoese from the Crimean coastal region. Under Ottoman rule, the Khanate's port city Kefe (formerly Caffa, today Feodosiia) became, by the early seventeenth century, one of the largest cities in Eastern Europe and a major center of the slave trade.

Read more...

The governing elite of the Crimean Khanate included the extended Giray family (direct descendants of Chinggis/Genghis Khan) based in Bakhchysaray and their allies, the Tatar tribal clan leaders. The latter administered large tracts of land in the Crimean steppe hinterland and mountainous regions. Most important for Ukrainian history were the Nogay tribes, who dominated the southern steppe of Ukraine. A portion of the Nogay Tatars became a nominal vassalage of the Crimean Khanate in the late sixteenth century. Though the Nogays often rebelled against the Crimean Khanate, they served a useful purpose from the Khanate's perspective — they prevented stable Slavic settlement of the steppes and were key provisioners of the Crimean slave market.

The Nogays engaged in regular raids on the East Slav populations, capturing hundreds of thousands to sell as slaves in the port of Kefe for the Crimean Khanate's massive slave trade with the Ottoman Empire. As a result, a large area of the steppes became mostly uninhabited no-man's-land, known as the Wild Fields. Both the Polish-Lithuanian state and Muscovy regarded this area as a borderland under the nomads' control and hired frontiersmen (who came to be known as Cossacks) to guard the restless borderlands.

sources and related

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 179–180, 187–188;

- "Nogay Tatars," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (2014).

Related

Chapter 4.1 1550s–1630s