1569–1648

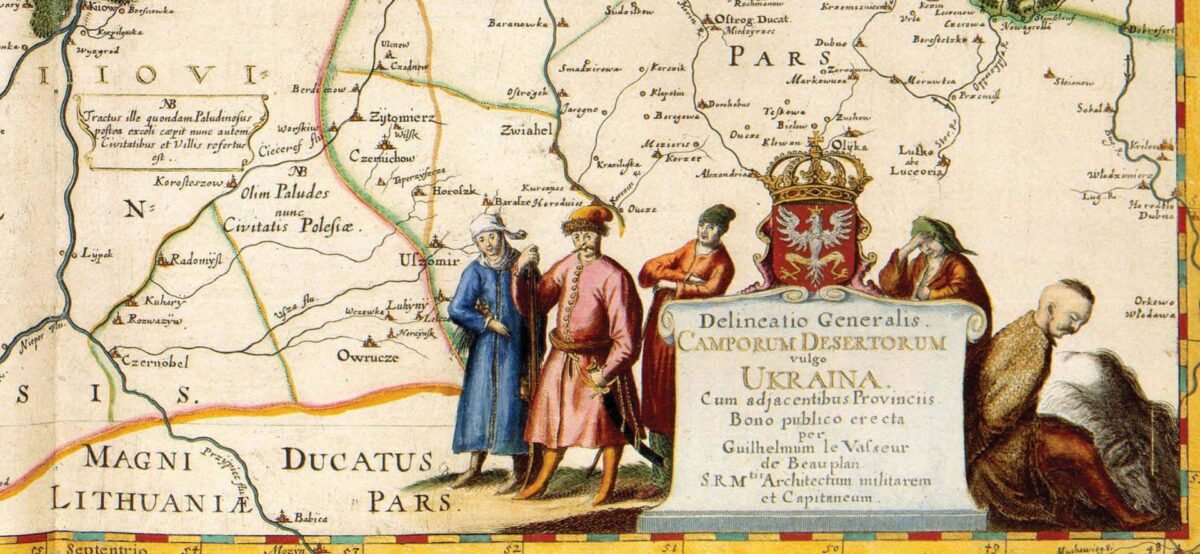

The creation of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth set in motion the migration of large numbers of peasants, as well as a wave of Jewish migration to Ukrainian lands further east.

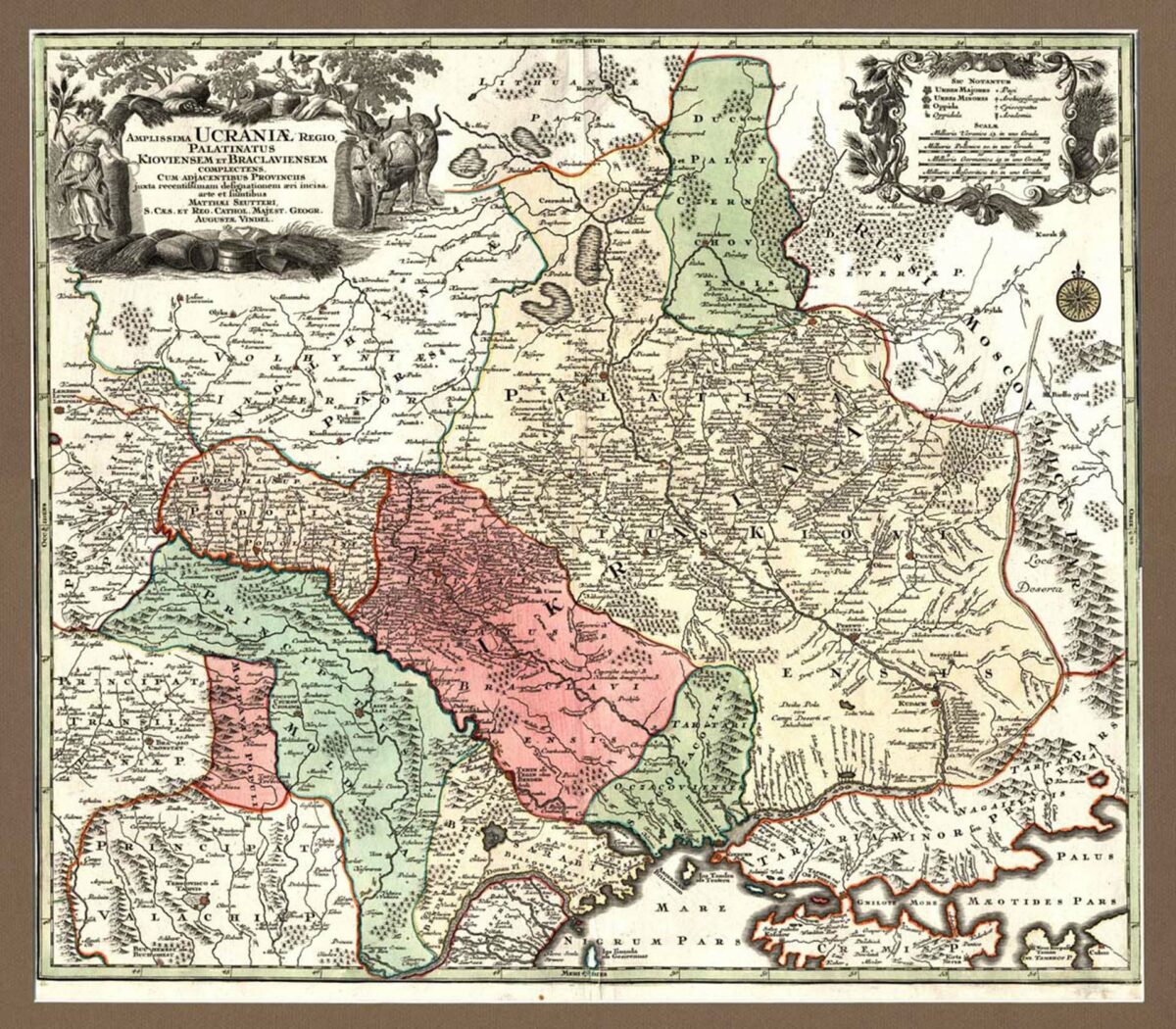

The estimated number of inhabitants in the Ukrainian territories annexed by Poland in 1569 was approximately 937,000. In addition, there were about 573,000 inhabitants in the largely Ukrainian-inhabited palatinates of Rus' (Galicia), Belz, and Podolia, which were already part of Poland. By the second half of the sixteenth century, Ukrainian-inhabited Galicia and western Volhynia, where serfdom had become widespread, became densely populated (14 inhabitants per square kilometre). In contrast, the eastern regions of Volhynia, Kyiv, and Bratslav, where large manorial estates (latifundia) were being formed and peasants had not yet been enserfed, were less densely populated (8 inhabitants per square kilometre).

Read more...

Settlement of the more easterly Ukrainian lands occurred under the auspices of magnates of both Rus' (Ukrainian) and Polish origin. The king granted the magnates official posts and vast tracts of lands on condition that they develop and attract settlers to these lands. A prime example is the Rus' Prince Kostiantyn Vasyl Ostrozky, who by 1590 owned, in the Kyiv, Galician, and Volhynian palatinates, approximately 1,300 villages, 100 towns, 40 castles, and 600 churches. A couple of decades later, the Vyshnevetsky family owned nearly the entire Left Bank of the Kyiv palatinate (then comprising 230,000 inhabitants), while in Volhynia, 13 noble families owned 57 percent of the land.

The Polish and Rus' magnates encouraged peasants from the more densely populated western regions to migrate to the lands they owned by offering them a significant period of exemptions from obligatory unpaid labour (corvée) and other concessions. They also invited Jews (and others) to inhabit and help develop the economy in the private towns they established and to manage their vast, newly acquired estates, often as leaseholders. At times, a Jewish leaseholder was able to sublease parts of his leased holdings to secondary leaseholders, often to other Jews, eventually leading to the formation of communities.

According to a 1980s scholarly estimate, the number of Jews in the four provinces of Volhynia, Podolia, Kyiv, and Bratslav rose thirteenfold in the eighty years after 1569, from 4,000 to 52,000. The increase reflects the migration of Jews from Poland, Lithuania, Italy, Moravia, and Germany, who settled into a frontier-like lifestyle, alongside non-Jewish neighbours, in 115 towns on the territory of Ukraine. A more recent estimate is that by 1648 there were about 40,000 Jews concentrated in around 200 communities in these same provinces, including Red Rus' (Red Ruthenia).

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 141, 151;

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford and Portland, OR, 2010), vol. I, 84;

- Shmuel Ettinger, "Jewish Participation in the Settlement of Ukraine in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries," in Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective, Peter Potichnyj & Howard Aster, eds. (Edmonton, 1988), 25;

- Shaul Stampfer, "Gzeyres Takh Vetat," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1567–1635

There was a Sephardi Jewish community in Lviv, consisting of around thirty merchants from Turkey and their families. They maintained links with Joseph Nasi, a court Jew of the Ottoman Sultans.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford and Portland, OR, 2010), vol. I, 13.

1600s–1760s

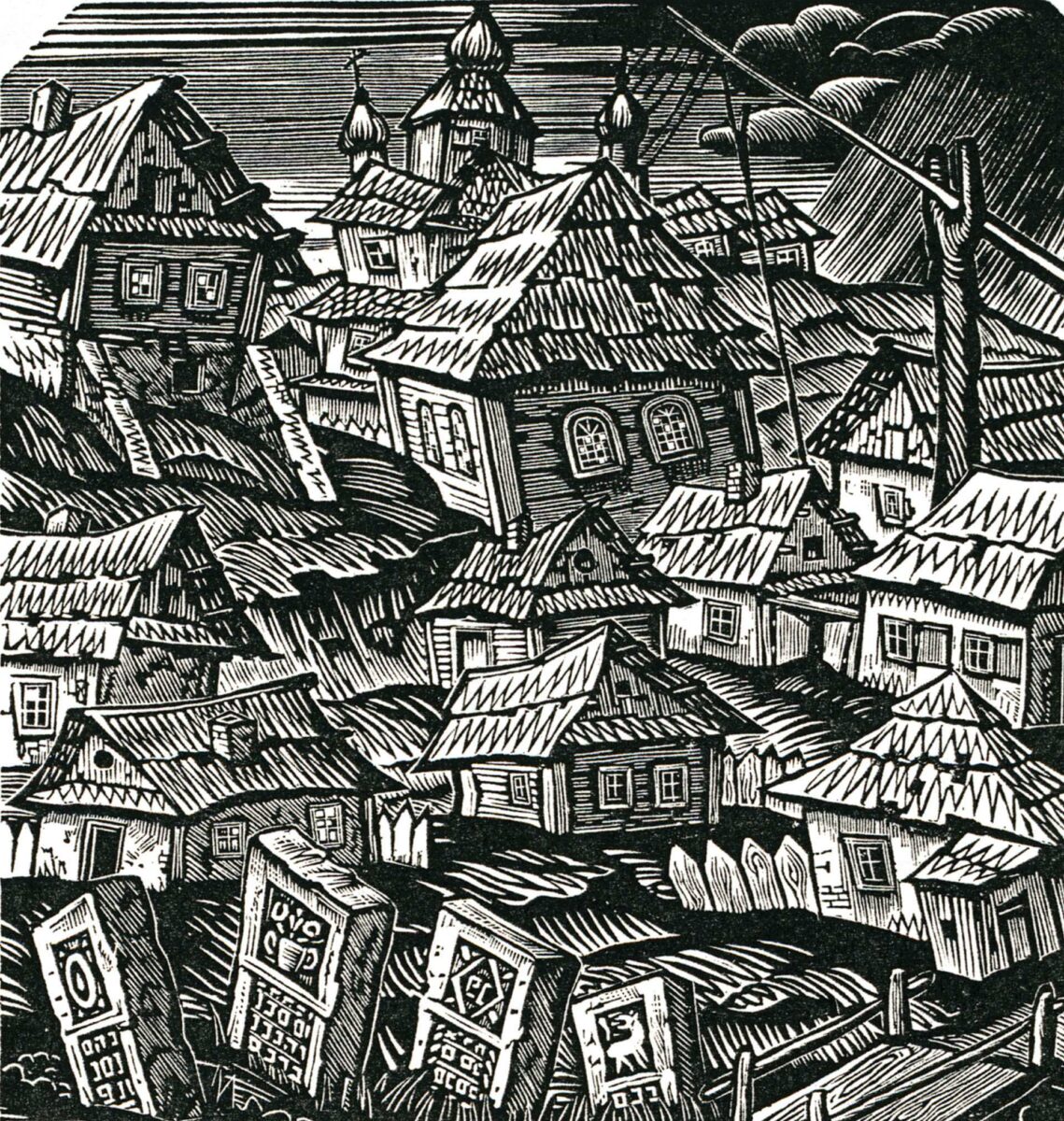

During this period, many of the Commonwealth's small private towns established on the estates of the nobility acquired significant Jewish populations, giving rise to the phenomenon of the shtetl (Yiddish: "small town"— akin to the Ukrainian word mistechko), later idealized in Jewish lore. The Jewish inhabitants of the shtetls were mostly Yiddish-speaking Jews of the Ashkenazi tradition, descendants of Germanic Jews who had settled in Bohemia, Poland and Lithuania since the twelfth century and migrated to Ukrainian lands since the sixteenth century.

Read more...

By 1764, some 750,000 Jews resided in nearly 1,150 Jewish communities on the territory of Poland-Lithuania, making it the largest Jewish center in the world. Of the sixteen largest Jewish communities, ten were in private towns, owned and controlled by nobles. Royal towns (such as Lviv, Cracow, and Vilna) remained important areas where Jews had their own sacred spaces, a sophisticated Jewish intellectual life, and opportunities to interact with the broader society. It is in some of the private towns, however, that Jews constituted a larger proportion (sometimes the majority) of the population and had more of a role in running the town's affairs and its economy.

Shtetl Jews regularly interacted with village Jews. Twenty-seven percent of the Jewish population (according to the 1764 census) lived in small rural communities, mainly in the eastern part of Polish-Lithuania. They were often the only or one of very few Jewish families in their village, and therefore would travel to a nearby shtetl for special occasions, sabbaths, and holidays.

As owners of houses and shops facing the market square, shtetl Jews also interacted with non-Jews of every class, including rural folk, who on market days would bring fresh produce to the town while looking for goods and services not available in their villages.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford and Portland, OR, 2010), vol. I, 84–88;

- Adam Teller, "The Jewish Town, 1648–1772, "Polin: 1000 Year History of Polish Jews (Warsaw, 2014), 134–135, 138.

1700s

The number of Jews in the Cossack Hetmanate was minuscule — about six hundred in the eighteenth century. Their absence was the result of a series of decrees issued by the Russian imperial government in response to Cossack leaders' demands to ban Jewish settlement on the Left Bank of the Dnieper. The majority of the Jews fled or were exiled westward to the Polish-ruled Right Bank; the few who remained converted to Christian Orthodoxy.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 295–96.

1764

The majority of Polish-Lithuanian Jews lived east of the Vistula in the regions of the Commonwealth where non-Polish ethnic groups predominated. Of the 750,000 Jews living in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, 44 percent (or 330,000) resided in Ukraine-Ruthenia). Of the 44 towns in the Commonwealth with a Jewish population of over one thousand, 27 were in Ukraine-Ruthenia. Nearly three-quarters lived in towns and villages controlled by local noblemen (rather than under royal authority). With 7,400 Jews, Lviv became the second-largest Jewish community in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The largest was in the private town of Brody, where 8,600 Jews resided.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford and Portland, OR, 2010), vol. I, 14–15, 71, 86;

- Moshe Rosman, "Poland: Poland before 1795," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).