1764–1786

Under Catherine II (Catherine the Great), Russia expanded into Ukrainian lands by both military and diplomatic means. Russia progressively abolished and absorbed the Ukrainian Cossack (Hetman) state (1764 and 1782); liquidated the Zaporozhian Host (1775) on the lower Dnieper following the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774; and eliminated the Crimean Khanate, annexing its territories (1783).

Read more...

In addition to acquiring territory in what today is southern Ukraine, the Russian empire began to colonize the region by establishing new cities, such as Kherson, Mykolaiv, and Odesa, and many towns and villages.

The expansion of Catherine the Great’s rule also meant the extension of serfdom to populations that had not previously known it, and the imposition of an administration and a culture that many would have perceived as foreign.

sources

- Lev Okinshevych, Arkadii Zhukovsky, "Hetman state," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1989);

- Arkadii Zhukovsky, "Zaporozhian Sich," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1993);

- Iaroslav Boiko, Zaselenie Iuzhnoi Ukrainy. Formirovanie etnicheskogo sostava naseleniia kraiia: russkie I ukraintsy (konets XVIII-nachalo XXI v.). Etnostatisticheskii ocherk (Cherkassy: Vertikal', 2007).

1792–1795

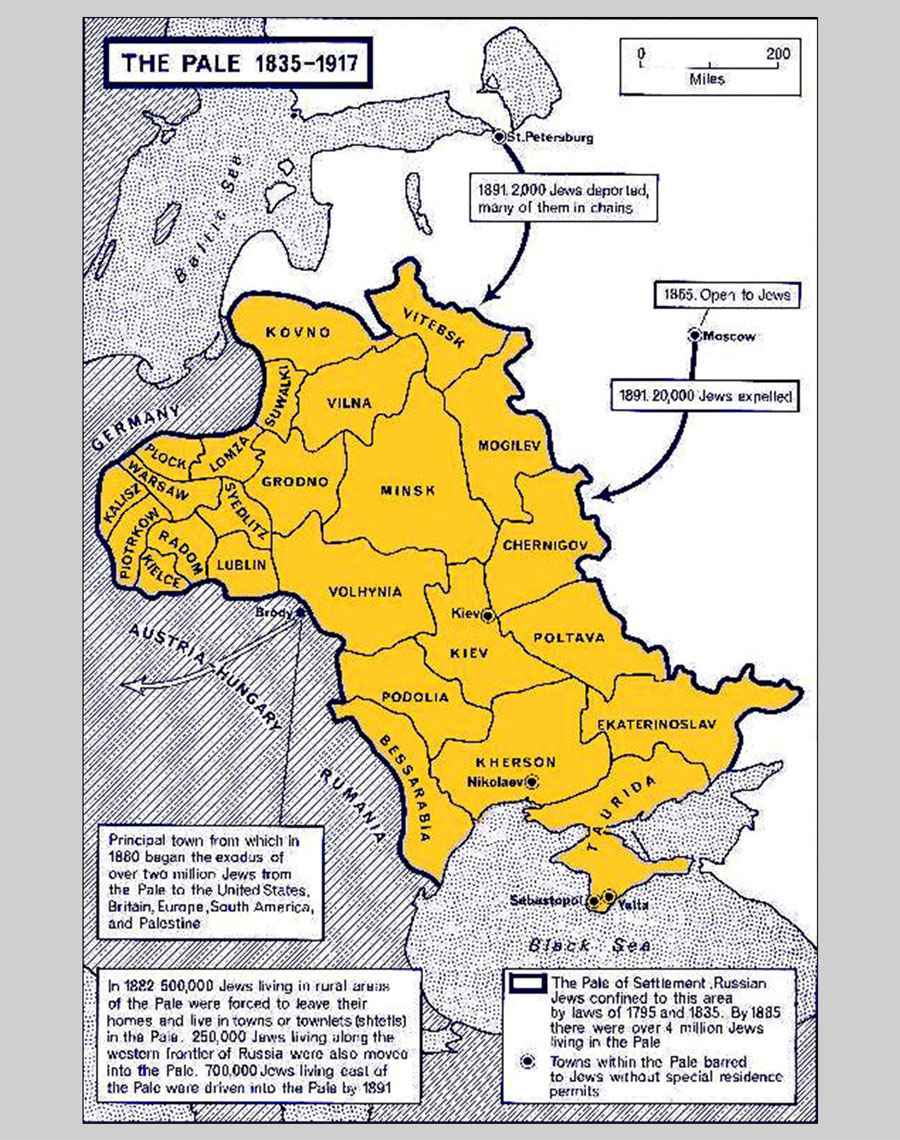

With the second and third partitions of Poland, the Russian Empire included close to 85 percent of Ukrainian lands. Empress Catherine II now ruled over 85 percent of the ethnic Ukrainian population and acquired the largest Jewish population in the world, numbering between 400,000 and 500,000 people. The Empress created what came to be known as the Pale of Settlement, prohibiting former Polish and Lithuanian Jewry from moving into the Russian heartland. Ukrainian lands became part of the Pale, with the incorporation into the Russian Empire of the palatinates of Kyiv, Bratslav, Podolia, and eastern Volhynia in 1793, and western Volhynia and Chełm (east of the Buh River) in 1795. The Russian Empire also consolidated its control over what today is southern Ukraine, following its victory over the Ottomans in 1792.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 318–19;

- Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe (New York, 2015), 361.

1790s

Although Empress Catherine II was influenced by the principles of European-style emancipation, the Jews she came to rule were subjected to contradictory sets of restrictions and privileges outlined in Russia's social estates classification system. They were classified simultaneously as Jews and as members of the main urban estates — the meshchanstvo (artisans and petty traders) or the kupechestvo (merchants). This classification system determined, among other things, the taxes one paid, whether one was subject to military service, and one's freedom to travel. As Jews, Catherine's newly acquired subjects were subject to one set of restrictions and privileges; as artisans or merchants, they were subject to another. Also, as many Jews lived in rural areas, local officials and the Jews' economic rivals had ample scope to interpret the law in their own favour.

sources

- Benjamin Nathans, "Estate System," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1796

Emperor Paul I, Catherine II's successor, acted tolerantly towards Jews. He opposed the expulsion of Jews from Kamianets-Podilskyi and Kyiv; opposed advice to question the validity of the oaths of Jews before the courts; and rejected blood libel accusations levelled against Jews. However, Jews were not explicitly mentioned in the guarantees of religious and other freedoms issued after the second and third partitions, and the principle of double taxation of Jews was maintained, as were severe restrictions on where Jews could reside.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) I, 337.

1790s–1804

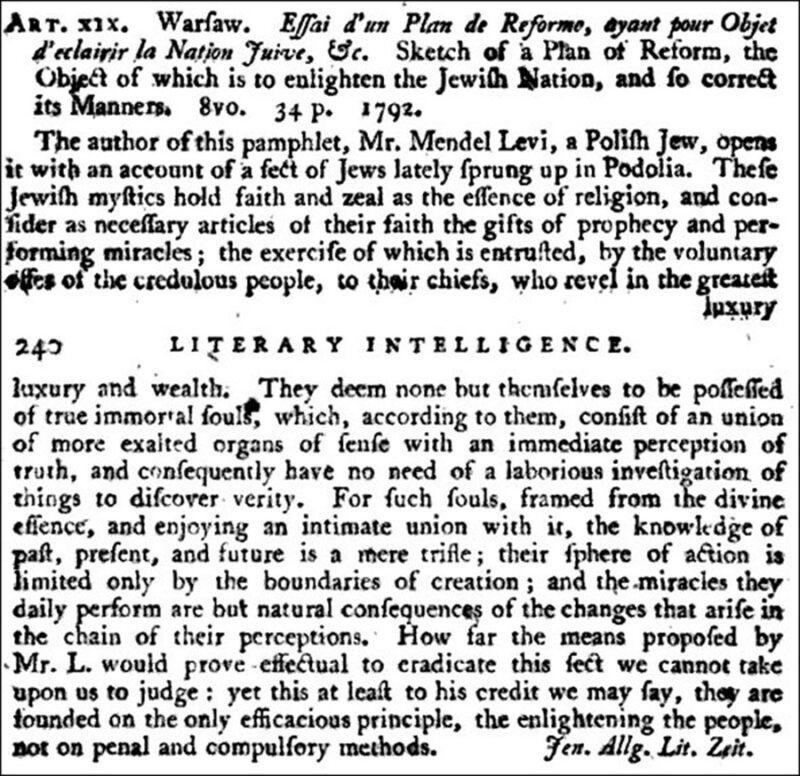

Influenced by the proponents of the Haskalah (the Jewish Enlightenment) in Berlin, Menahem Mendel Lefin of Sataniv (Podolia) published, anonymously, a French-language pamphlet (Essai d'un plan de réforme ayant pour objet d'éclairer la Nation Juive en Pologne et de redresser par là ses mœurs), which paved the way for bringing the Haskalah movement to Eastern Europe. Lefin called for the abolition of special taxes on Jews, in return for which the Jews would transform themselves through reform of their educational system, introduction of Polish as a language of instruction, and productive work in handicrafts and agriculture. Enabled by the patronage of Adam Kazimierz Czartoryski, a leading figure of the Polish Enlightenment, Lefin participated in the debates during the Four-Year Sejm (1788–1792) about reforms pertaining to Jews.

Read more...

After the 1795 partition of Poland, Lefin influenced discussions on reforms affecting Jews under Tsar Alexander I, including the edicts of 1804. Lefin later published critiques of the Hasidic movement, translations of European literature into Yiddish, and didactic works, including an ethical text, Sefer ḥeshbon ha-nefesh (Moral Accounting, 1808), inspired by Benjamin Franklin's program of moral self-improvement. In contrast with other pioneers of the Haskalah, who wrote in flowery Hebrew or German, Lefin chose to bring Enlightenment ideals to East European Jews in their own vernacular Yiddish. Lefin influenced a generation of leaders of the Haskalah in Austrian Galicia — in particular in Brody and Ternopil, where he resided in his later years.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) I, 206;

- Nancy Sinkoff, "Lefin, Menaḥem Mendel," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1804–1835

The Pale of Jewish Settlement

Two statutes — the first in 1804 and the second in 1835 — enacted measures to regulate the life of Jews in the empire, including where they could reside, their economic occupations, education, and taxation burden. The 1804 Statute on the Organization of the Jews, promulgated under Alexander I, limited Jewish settlement to the largely Ukrainian-inhabited provinces annexed from Poland and the areas north of the Black Sea, recently acquired from the Ottoman Empire. Preceded by deliberations of a special state committee established in 1802, the statute combined Enlightenment-derived ideas about "reforming" the Jews and a Russian preoccupation with the need to limit the "harmful impact" of Jews on the peasantry.

Read more...

Measures to reform the Jews included opening state schools to Jewish children, offering incentives for Jews to engage in industry and handicrafts (rather than commerce), and encouraging them to become farmers in the sparsely populated regions of southern Russia. At the same time, drastic measures were decreed to expel Jews from villages within three to four years and to prohibit them from lease holding, innkeeping and the sale of alcohol. The strong case made by the Jews' supporters — regarding the valuable role of Jews and local taverns in linking peasants with wider markets and providing needed goods not produced in the villages — had little impact. However, the statute did abolish the oppressive double taxation of Jews.

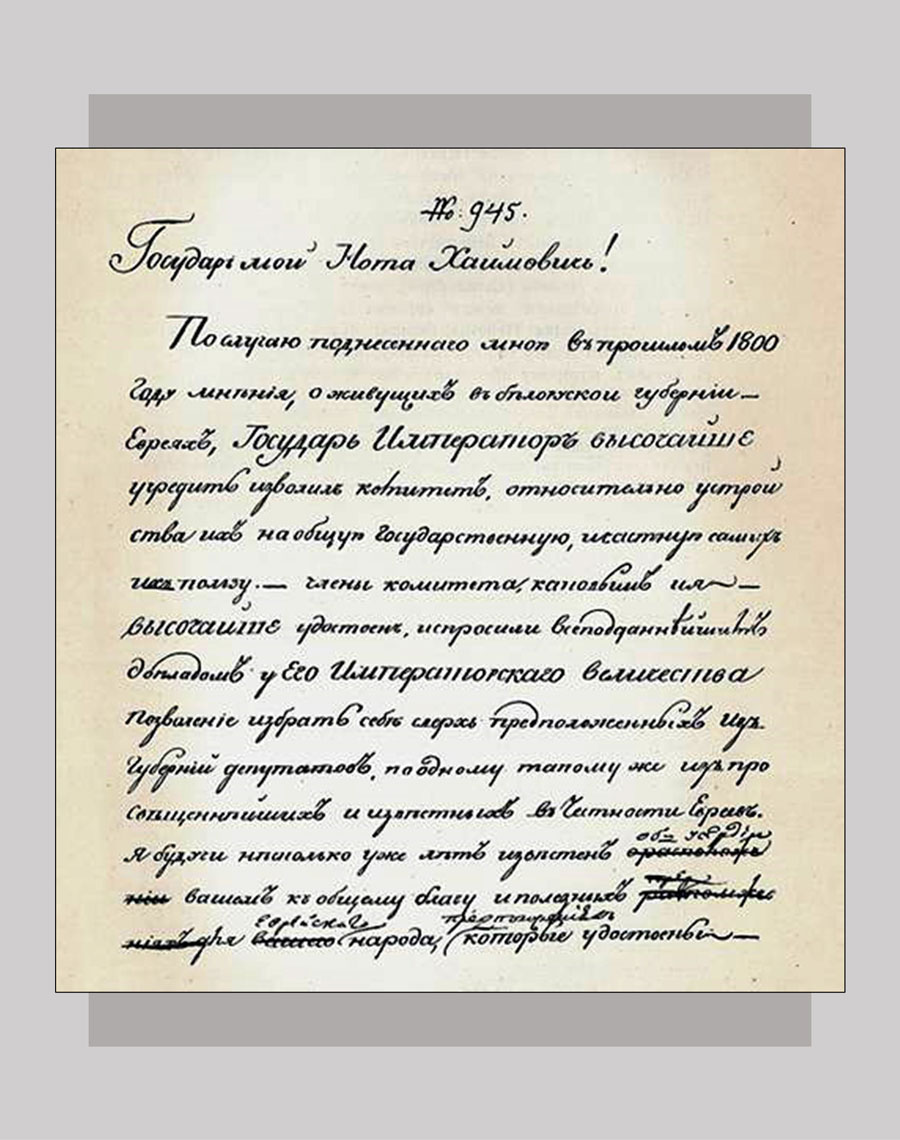

When the expulsion of Jews from the villages commenced in 1807, representatives from Jewish communities, including Kyiv, and many government officials protested. In response, a commission was appointed to re-examine the situation. Its finding — that Jews were not causing harm to the villages but rather were useful for purveying commodities, maintaining links with the town, and transmitting post — did not lead to a reversal of the expulsion. However, lobbying efforts to keep traditional Jewish self-governing arrangements largely intact did succeed. The statute did not include the creation of an overriding, government-controlled Jewish religious authority, the Sendarin [sic. Sanhedrin], a concept proposed by Count Gavriil Derzhavin but strongly opposed by Kyiv's Jewish community and the prominent merchant, Nota Khaimovich Notkin.

The second statute on the Jews, promulgated under Tsar Nicholas I in 1835, formally established the borders of the Pale of Settlement (in effect until World War I).

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) I, 343–347, 362–363;

- Shmuel Ettinger, "The Modern Period," in A History of the Jewish People, H.H. Ben Sasson (Cambridge, Mass., 1976), 757–758;

- David E. Fishman, "Notkin, Nota Khaimovich," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1810

Supporters of the Haskalah movement in Russia allied themselves with the tsarist government in its effort to "modernize" Jews — which in effect meant assimilation and russification. Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav (1772–1810), the influential Hasidic leader, upon meeting three supporters of the Haskalah in Uman, referred to them as "these heretics [who] were important men close to the government."

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) I, 366.

1812–1850s

Cossacks and peasants in the Imperial Russian Army

Ukrainian Cossacks fought in the ranks of the Imperial Russian Army against Napoleon. Their presence in the Imperial Russian Army began after the destruction of the Sich and traditional Cossack military social structures. While some Cossacks were drafted into the imperial army, others were left in Zaporizhia as free farmers or emigrated to towns and cities to become merchants and artisans, or fled southward to the Ottoman Empire.

Read more...

The Cossack regiments of the Hetmanate were integrated into the imperial army around 1783. After that, there were no Cossack regiments in Zaporizhia or the Hetmanate, but Cossack formations remained in Sloboda Ukraine and Kuban. Cossack units were recreated around 1812 at the time of the Napoleonic wars. Among the organizers of the Cossack regiments in Poltava gubernia was the pioneer of modern Ukrainian literature, Ivan Kotliarevsky.

In addition to the Cossacks, serfs volunteered for service to escape from their oppressive condition. The total number of Ukrainian troops, peasant and Cossack, in the imperial army in 1812 was almost 75,000. The local population supported them by providing horses, arms, uniforms, and supplies.

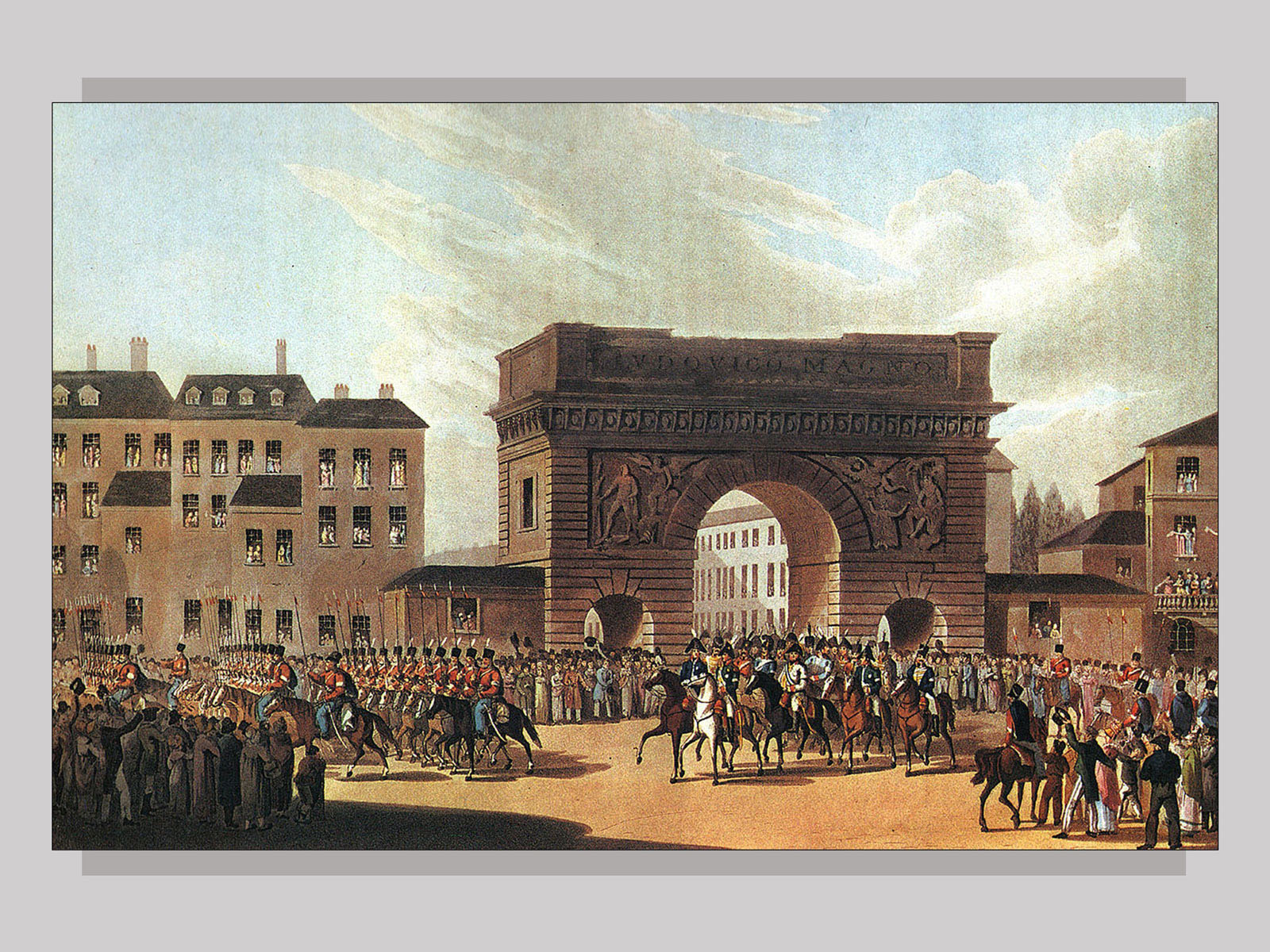

In 1813–1815 some Cossack regiments took part in the war against Napoleon in central and western Europe and in the occupation of Paris. There they discovered western ideas of individual liberty and human rights. After the war, some of the regiments were converted into regular Russian units. The rest were demobilized and returned to the peasant estate.

sources

- Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe (New York, 2015), 361;

- Serhii Plokhy, The Cossack Myth: History and Nationhood in the Age of Empires (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2012), 19-21, 164–165;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 336–337;

- "Ukrainian regiments in 1812," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine;

- "Kotliarevsky, Ivan," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine.

1825–1856

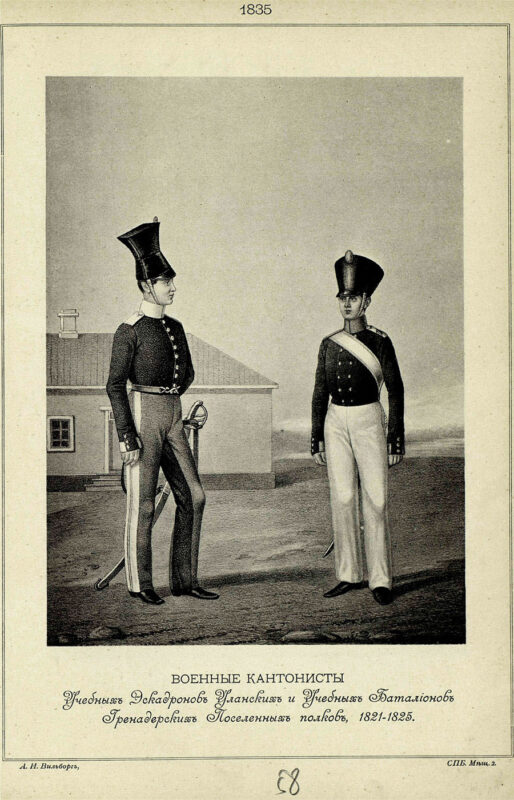

Jews in the Imperial Russian army

Tsar Nicholas I adopted strongly interventionist measures designed to modernize and mould Jews into loyal subjects, imposing direct state supervision over their religious and communal lives. Measures included the establishment of state-controlled Jewish schools, promotion of crown (state-paid) rabbis, and compulsory conscription (with a few exempt categories) into the tsarist army, according to a designated quota system. Jewish communal leaders endeavoured, in vain, to prevent the law on Jewish conscription from being implemented. They also had limited success in negotiating arrangements to respect Jewish soldiers' privilege to practice Judaism.

Read more...

All recruits, including Jews, had to serve in the army for 25 years, and their sons had to attend the "canton" schools for soldiers' children for training for future military service. However, a different policy applied to Jews. Jews were required to provide conscripts between the ages of 12 and 25, whereas for others, the conscripts were between 18 and 35. In addition, some 40,000 Jewish boys were drafted, between the ages of 8 and 13, to the canton schools, alongside boys of other creeds. Unlike Russian Orthodox cantonists, however, Jewish and Polish Roman Catholic boys were not allowed to live with their parents while studying in the cantonist schools. In these schools, they were openly pressured to convert to Russian Orthodoxy. Historian Michael Stanislawski estimates that at least half of the cantonists and a substantial number of adult recruits were converted.

After 1827, when Jewish communal leaders were authorized to compose the draft lists, they based their decisions on local communal dynamics and economic considerations. Consequently, the sons of tax-paying middle-class families were mostly exempt, while "non-useful Jews" — single men, heretics (including "modernists" and maskilim), beggars, and orphans — were drafted. As selection practices became increasingly despotic, families turned their anger against community leaders, leading to violent protests. For example, in Bershad (Podolia) in 1827 and subsequently in several Volhynian towns, the communal leaders encountered intense resistance. Some communal leaders, who used their power to suppress protests and intimidate potential informers to the government about the arbitrary practices, lost the trust of the people.

When quotas for Jews quadrupled during the Crimean War, community leaders resorted to hiring special officials (graphically named khappers — catchers) to kidnap whomever, including underage Jewish boys, in order to fill the quotas. In Jewish memory, the three-year period of the khappers symbolized Nicholas I's entire conscription system and undermined Jewish communal authority structures.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) I, 359–362;

- Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, "Military Service in Russia," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010);

- Michael Stanislawski, "Russia: Russian Empire," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1830s

Revolts in Podolia

In eastern Podolia, the intensification of serfdom gave rise to peasant discontent and the revolts led by Ustym Karmaliuk in the 1830s. These revolts — which spread into Podolia's neighbouring regions of Kyiv, Volhynia, and Bessarabia — involved up to 20,000 peasants in some 1,000 raids on landowners' estates. Purportedly, many Jews and even some Poles supported the revolts.

[Note: Podolia (Podilia), with its dense Ukrainian and Jewish populations and significant Polish presence, has a unique political history. With the First Partition of Poland (1772), western Podolia, east of the Zbruch River, was annexed by Austria, and with the Second Partition (1793), eastern Podolia was transferred to Russia.]

sources

- Volodymyr Kubijovyč, Ihor Stebelsky, Mykhailo Zhdan, "Podilia," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine, (1993);

- "Karmaliuk, Ustym," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1988).

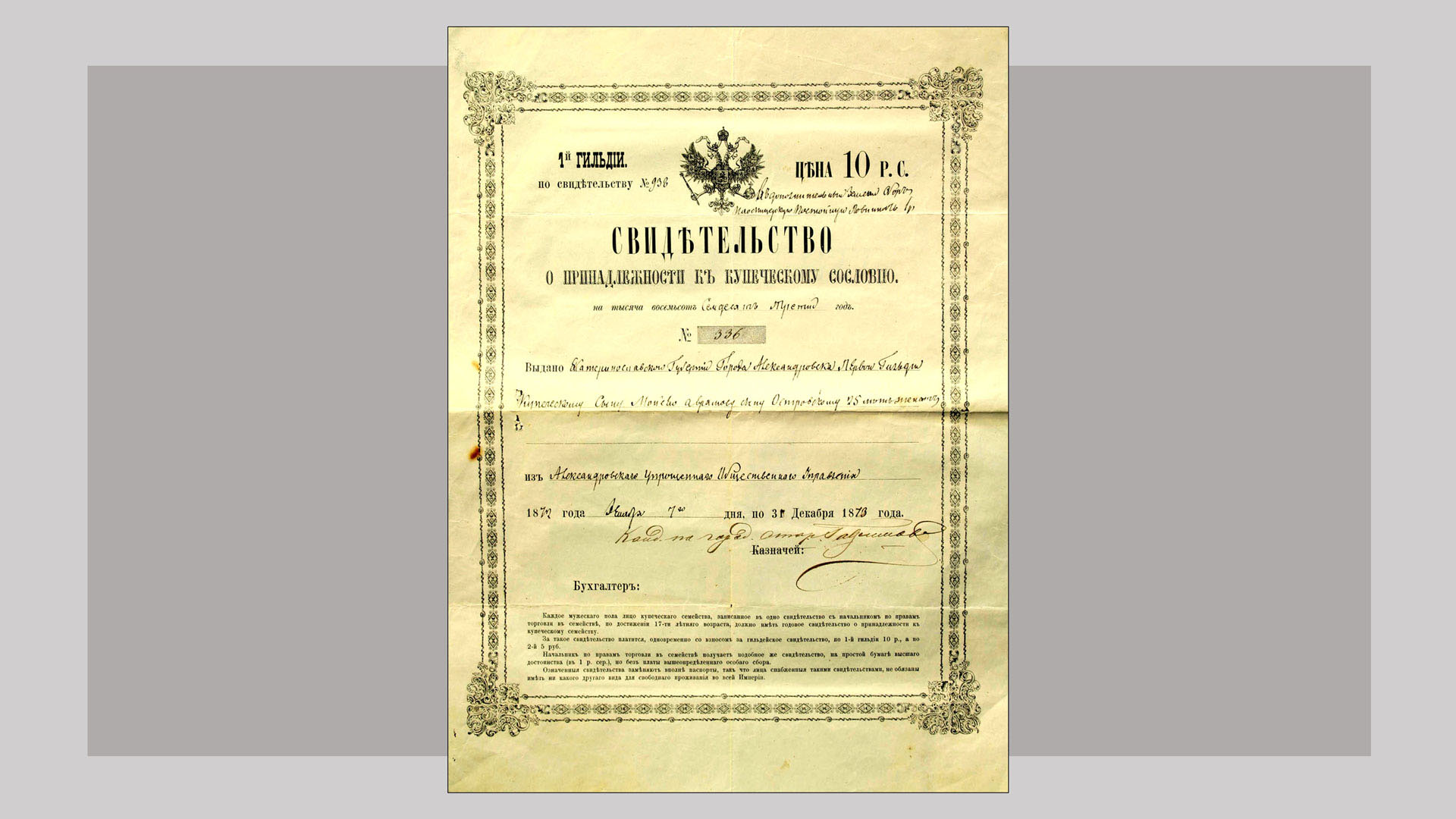

1835

Under Tsar Nicholas I, a new statute on the Jews was promulgated, formally establishing the borders of the Pale of Settlement (in effect until the First World War). Within this area, forced resettlement of Jews from the countryside no longer applied, and Jews had the right to buy, work, or lease land — except for settled estates and properties on which Christian serfs lived. They could also establish factories and lease rural enterprises within these boundaries, including taverns, inns, and mills. Some Jews, under specified conditions, were allowed to reside outside the Pale, and Jewish First Guild merchants were permitted to travel to capital cities and seaports.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) I, 362.

1844

Abolition of Jewish self-government

The government of Tsar Nicholas I formally abolished the kahal system of Jewish self-government, placing Jews under the legal jurisdiction of local state authorities. Jews were permitted to run their own affairs only insofar as these related to Jewish religious practice.

sources

- Michael Stanislawski, "Russia: Russian Empire," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1845–1848

The Cyril and Methodius Brotherhood, a secret society whose aim was to transform the social order "according to the Christian principles of justice, freedom, equality, and brotherhood," was established in Kyivat the initiative of the historian/writer Mykola Kostomarov. The society advocated the abolition of serfdom, equal opportunity for all Slavic nations to develop their national language and culture, education for the masses, and unification of all Slavs in a federated state in which Ukraine would play a leading role. Kostomarov developed the idea of such a Slavic federation in 1845–1846 in The Book of the Genesis of the Ukrainian People, described as "the first political program of the nascent Ukrainian movement." After being denounced to the authorities, some of the society's members and associates — including the writers Panteleimon Kulish and Taras Shevchenko — were arrested and exiled or imprisoned. Despite its brief existence, the society had an impact on its contemporaries and, through later publications of its members, an even more significant impact on the development of the Ukrainian national movement.

sources

- Ivan Koshelivets, "Cyril and Methodius Brotherhood," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine.(Article updated in 2020);

- Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe (New York, 2015), 362.

1853–1855

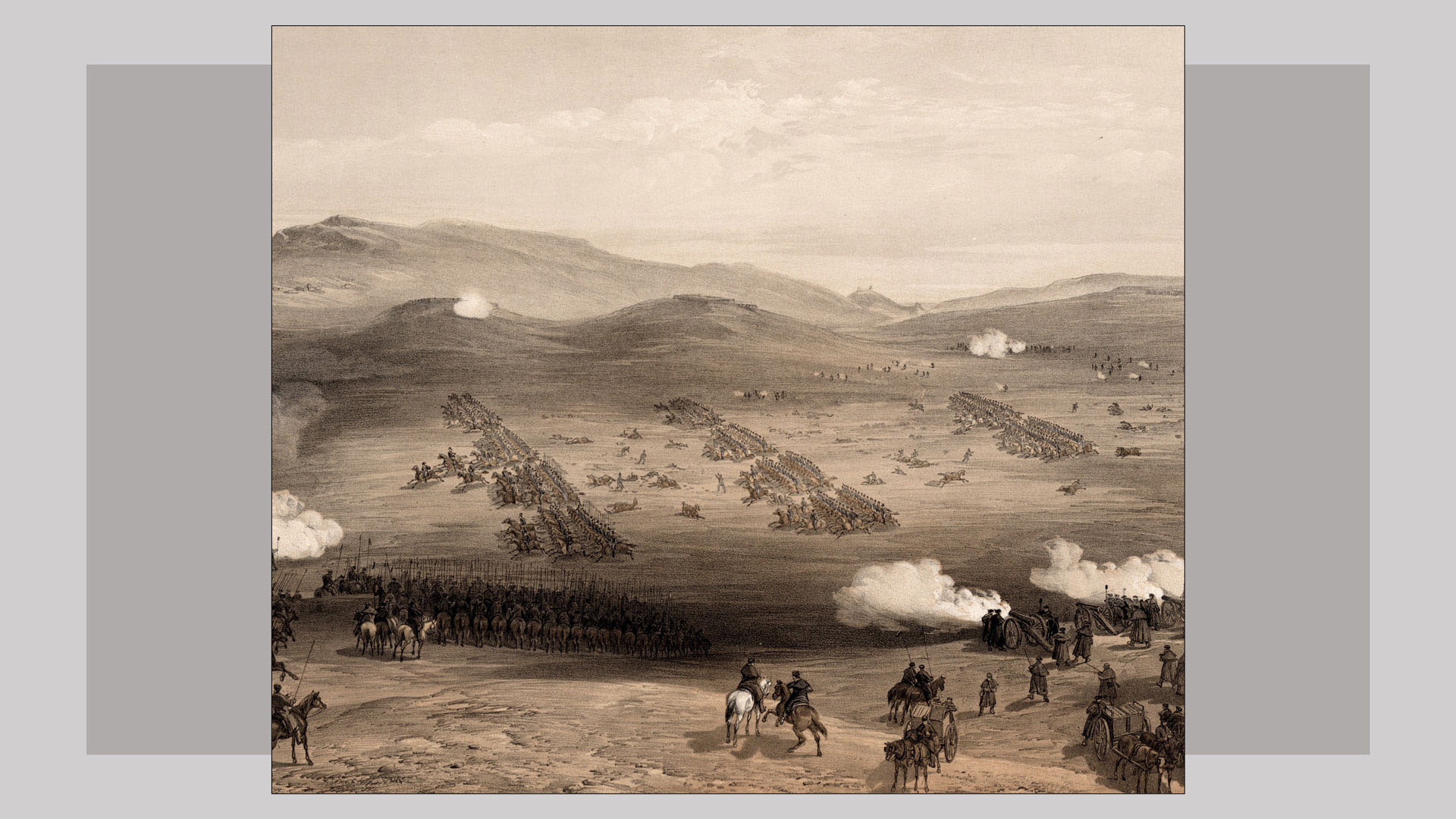

The Crimean War

The Crimean War had profound consequences for Jews, Ukrainians, and others in the Russian Empire. The war had pitted the Ottoman Empire and its allies (including Britain, France, and Sardinia) against Russia, then attempting to extend its empire and influence in the Near East. British, French, and Ottoman forces landed in the Crimea in September 1854, initiated a year-long siege of Sevastopol, and engaged in a series of battles that ended with the defeat of Russia and the loss of its Black Sea fleet.

During the war, the quota of recruits for the Russian army doubled for Russians and Ukrainians and quadrupled for Jews. Hundreds of Jewish soldiers and sailors participated in the defence of Sevastopol. In the course of the war, there were heavy casualties on all sides.

Read more...

The war also damaged the economy of the empire, especially Ukraine, which was part of the theatre of action. Ukrainian landowners and commercial circles had opposed the war, and there was growing peasant unrest. A broadly transformative consequence was that Russia's loss to Britain and France provoked extensive soul-searching in both the Russian government and society. The war had demonstrated the inefficiency of Russia's military command and its system of transport and supplies, conveying a sense that the Russian Empire was backward in comparison to Europe. Embarrassingly for Russia, the British built the first railroad in the Crimea (the first in Ukraine) to connect Balaklava (site of the controversial failed British military action of the Light Brigade) with Sevastopol.

Demands for change spurred tsar Alexander II, who ascended the throne just as the war ended, to launch an ambitious reform program to modernize the empire. The reform program directly affected the abolition of serfdom in 1861 and energized political activism to assert civic rights for both Ukrainians and Jews, among others. The war also changed the human and cultural landscape of the Crimea, as Alexander II adopted a hostile policy regarding the Crimean Tatars, driving over 200,000 of them to leave for the Ottoman Empire over the next decade — soon to be replaced by Slavic (Ukrainian and especially Russian) in-migrants.

sources

- Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe (New York, 2015), 176, 362;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, 2010), 340, 367–368;

- Lubomyr Wynar, "Crimean War," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1984);

- Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, "Military Service in Russia," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1855–1865

The Great Reforms

Tsar Alexander II introduced the "Great Reforms" that led to the emancipation of serfs and transformed the economic, social, and cultural landscape of Ukraine, directly affecting the lives of both Ukrainians and Jews. The emancipation of the serfs in 1861 freed 23 million of the Empire's population of 74 million — including the majority of the Ukrainian population in the provinces of Kyiv, Podolia, and Volhynia — from personal and legal subjugation to landlords and enabled them to purchase farms. Despite emancipation, however, the economic status of former serfs did not improve in the ensuing complicated system of communal land ownership. Nor did they obtain any political influence or encouragement to develop their distinctive culture. On the contrary, alarmed by the 1863 Polish insurrection and the possibility of a split within the "all-Russian nationality," the Russian minister of the interior, Petr Valuev, introduced a ban on Ukrainian-language publications. The reforms of Alexander II expanded the policy of integration of Jews into the Russian body politic, but under a far more liberal regime than that of his predecessor.

Read more...

Measures included outlawing conscription of children, opening additional areas outside of the Pale to Jewish residence, and lifting some economic and educational restrictions against Jews. A significant change was to permit certain categories of Jews — such as university graduates, military veterans, first-degree merchants, and certified artisans — to settle permanently in Kyiv, where Jews were not allowed to reside following the 1835 statute that established the borders of the Pale of Settlement.

However, these reforms benefitted primarily acculturated Jews and more privileged groups. At the same time, poverty remained widespread within the broader Jewish population. The educational advancement and professional success of some Jews soon provoked resentment within the general population and calls to re-introduce restrictions on Jews. By 1865, a number of reforms were cut back, and after the tsar's assassination in 1881, Tsar Alexander III reversed many of his father's liberal reforms.

sources

- John Klier, "Pale of Settlement," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010);

- Benjamin Nathans, Beyond the Pale: The Jewish Encounter with Late Imperial Russia (Berkeley 2002), 78;

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) I, 397–399.

1864

The tsarist reform of local government enabled those Jews who satisfied the requirements of the property-qualified franchise to vote and be elected to the newly established district and provincial assemblies (zemstva). As a result, Jews began to participate in rural assemblies and occasionally were appointed to political office at the local level in Ukraine's rural regions.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) I, 401.

1850s–1905

Ukrainian populist movements

Beginning in the late 1850s, populist members of the Ukrainian intelligentsia formed clandestine societies called hromadas, which played a significant role in animating the growth of Ukrainian national consciousness within the Russian Empire. They took the name hromada (Ukrainian: commune or community), the name for the traditional village association, because they were reaching out to the largely rural population. Through publications and Sunday schools, they aimed to spread literacy among Ukrainian peasants and workers, educate them about Ukrainian culture, instill in them a sense of national identity, and improve their living standards. Not only Ukrainians but also Jews taught the urban poor in these Sunday schools.

Read more...

A remarkable fact is that the Sunday schools (first opened in Kyiv in 1859) were most likely patterned on Jewish Sabbath schools for artisans in Odesa. Such schools were the product of Jewish educational reform associated with the Jewish Enlightenment movement and supported by Nikolai Pirogov, a renowned surgeon and liberal thinker, then a curator of the Odesa school district. The first Sabbath school had opened in Odesa ten months before the first Sunday school was founded in Kyiv.

The hromada in Kyiv was the most active and enduring in Russian-ruled Ukraine. By the 1870s, hromadaswere established in Kharkiv, Poltava, Chernihiv, Odesa, and other cities (with influential branches also in Saint Petersburg, Moscow, and Warsaw). The larger hromadas organized drama groups and choirs, staged Ukrainian plays and concerts, and printed educational booklets for distribution in villages.

As anti-Ukrainian repressive government measures increased in the 1860s (particularly the ban on publishing Ukrainian books and the closing of Ukrainian Sunday schools), surveillance and repression of leading hromada activists intensified. The older hromadas responded by focusing on politically neutral cultural and educational activities. However, more politically oriented hromadas emerged at the turn of the century, consisting mainly of secondary school and university students, including women. Examples include the student hromada founded in Kharkiv in 1897 by Dmytro Antonovych, which in 1904 merged with Antonovych's illegal Revolutionary Ukrainian Party (RUP), and the Kyiv student hromada, also linked to the RUP, which was decimated by arrests in 1904–05.

sources and related

- Vasyl Markus, "Hromadas," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1989);

- Tobias Grill, “Rabbis as Agents of Modernization in Ukraine, 1840-1900,” in Martin Schultze Wessel and Frank E. Sysyn, eds., Religion, Nation, and Secularization in Ukraine (Edmonton and Toronto, 2015), 73.

Related

Chapter 6.1 1897–1908

1860s–1880s

While Jews played no part in the first socialist groups organized in the Russian Empire, a few supported the Narodniks' agrarian socialist movement and other populist revolutionary groups in the 1870s. However, their commitment waned when elements within these groups expressed antisemitic attitudes at the time of the 1881 pogroms. After the first wave of pogroms, the Narodnaya Volya ("People's Will") Party, which was responsible for the assassination of Tsar Alexander II that triggered the pogroms, issued a provocative leaflet in Ukrainian. The leaflet called on peasants to rise against their Jewish oppressors and against the "tsar of the pans (nobility) and the Zhids."

Read more...

Recent research has established that the author of this leaflet, Herasym Romanenko, published it in August 1881 without the consent of remaining members of the People's Will (many of whom had already been executed or arrested), and that the remaining leaders of the People's Will denounced the proclamation. Some revolutionary populists, however, regarded Jewish victims as collateral damage, useful for triggering the desired peasant rebellion.

During this period, the tsarist regime considered all unauthorized parties, especially socialists and anarchists, as highly suspect. The authorities were determined to forcefully suppress efforts to propagandize revolutionary and socialist ideas among factory workers and peasants, and assigned the tsarist secret police (Okhrana) with the task of identifying, arresting, and jailing agitators.

sources

- Shmuel Ettinger, "The Modern Period," in A History of the Jewish People, H.H. Ben Sasson (Cambridge, Mass., 1976), 884, 908;

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) I, 433;

- Aleksei Miller, “Imperiia Romanovykh i evrei,” in his Imperiia Romanovykh i natsionalizm (Moscow, 2006), 138, 140;

- Christopher Ely, Underground Petersburg: Radical Populism, Urban Space, and the Tactics of Subversion in Reform-Era Russia (DeKalb, Ill, 2016), 268–269;

- John Klier, Russians, Jews, and the Pogroms of 1881–1882 (Cambridge University Press, 2014), 155–173.

1881–1883

The anti-Jewish “May Laws”

The economic, social, and political situation of Jews in the tsarist empire deteriorated sharply following the assassination of Alexander II, stirring Jewish nationalist aspirations. Reasons included disillusionment with policies pursued during Alexander II's reign for the integration of the Jewish community through education and Russification; anti-Jewish attitudes of officials, inclined to blame the Jews for the disruptive effects of industrialization and modernization and other societal ills; and a wave of pogroms beginning in April 1881. Making matters worse, the tsarist authorities responded to the pogroms by introducing the "temporary" May Laws in 1882, which restricted residence of Jews even within the Pale of Settlement and drastically limited their economic occupations.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) II, 1, 5;

- Michael Stanislawski, "Russia: Russian Empire," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

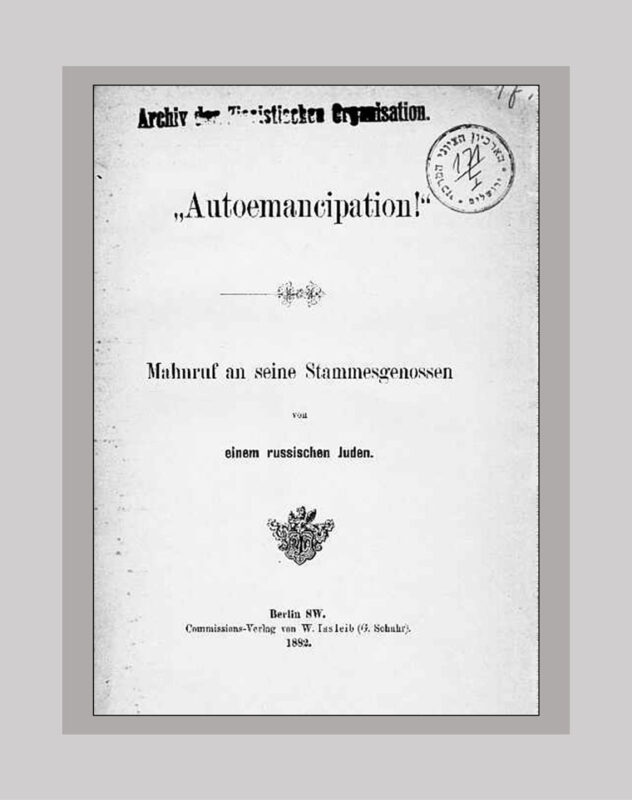

1882–1883

Jewish nationalism

Leon Pinsker — an Odesa physician and, earlier, a proponent of the integration of Jews into Russian society — published his influential pamphlet Autoemancipation, in which he presented a Jewish nationalist response to the 1881–1882 pogroms. Pinsker considered that antisemitism was not a fleeting remnant of medieval religious prejudice but a consistent modern phenomenon, a disease passed from generation to generation. The only cure for this disease is for Jews to become an autonomous polity. In Pinsker's view, the Christian world's Judeophobia stemmed from the unnatural, ghost-like situation of the dispersed Jewish people, regarded everywhere as alien. He advocated "normalizing" the situation by establishing the Jewish people on a territory of their own, like the other peoples coming to political maturity in nineteenth-century Europe.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) II, 22–23;

- Michael Stanislawski, "Ḥibat Tsiyon," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1883–1887

The Pahlen Commission

Among the various committees established by the tsarist regime to investigate the status of the Jews in the empire following the 1882 May Laws, the most noteworthy and long-lived was the commission chaired by Count Konstantin Pahlen. This commission spent five years collecting extensive data on Jews, their legal status and economic activities. Eventually, the majority of the members of the Pahlen Commission endorsed gradual Jewish emancipation and the removal of virtually all discriminatory legislation vis-à-vis Jews in order to equalize them with the rest of the population. However, Tsar Alexander III and his close advisors did not accept these recommendations and concurred with the minority view, which advocated the continuation of existing restrictions.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) II, 11–13;

- Shmuel Ettinger, "The Modern Period," in A History of the Jewish People, H.H. Ben Sasson (Cambridge, Mass., 1976), 884.

1870s–1890s

Early Zionism

A variety of precursor groups to the Zionist movement emerged in tsarist Russia after leading Jewish intellectuals, some with strong links to Odesa, applied the principles of nineteenth-century European nationalism to the case of Jews.

In the aftermath of the pogroms in the early 1880s, Perets Smolenskin, Mosheh Leib Lilienblum, and Leon Pinsker abandoned their earlier beliefs that Jewish nationalism could succeed on Russian soil and activated the Hibat Tsiyon (Love of Zion) movement. Eliezer Perelman, later better known as Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, argued by the late 1870s that Jewish nationalism could only be based in the Land of Israel, in a Hebrew-speaking Jewish commonwealth.

Read more...

When Theodor Herzl founded Zionism as an organized political movement in 1897, hundreds of thousands of Jews from Ukrainian lands, who had affiliated with the earlier Jewish nationalist movements, joined the new Zionist movement. However, vocal groups of critics objected to Herzl's political 'negation of diaspora' vision. Some took their lead from Asher Ginsberg, better known as Ahad Ha-am, who advocated the creation of a 'spiritual center' on the historic soil from which the Jewish people had sprung. Such a center would integrate ancient Hebraic and Rabbinic Jewish culture and ethics with the best elements absorbed from other cultures and modernity. The spiritual center would radiate a beneficial cultural and ethical influence over the entire Jewish diaspora, eventually transforming Judaism from a moribund faith into a vibrant, modern national culture.

From a different perspective, the vast majority of traditionalist East European rabbis strongly opposed activist Zionism of any kind as heretical. In their view, the national redemption in the Holy Land was to be accomplished by heavenly rather than human action.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) II, 22–24;

- Steven J. Zipperstein, "Ahad Ha-Am," and Michael Stanislawski, "Russia: Russian Empire," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

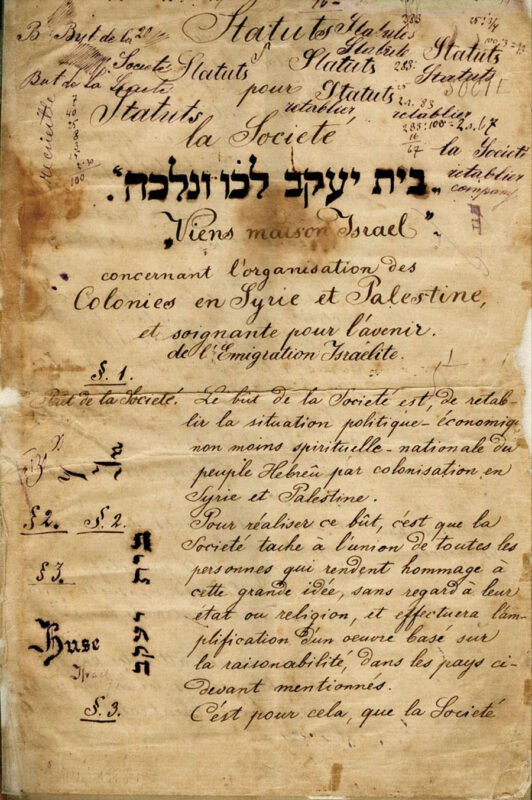

1882–1890s

Dnieper Ukraine saw the rise of some of the earliest movements promoting the idea of Jewish emigration to Palestine (Eretz Yisrael). The organization BILU (acronym for the biblical phrase "House of Jacob, come, let us go"), founded in 1882 by Jewish students in Kharkiv, was the first Zionist pioneering movement, predating the organized worldwide Zionist movement by fifteen years. Two years later, the Hibat Tsiyon (Love of Zion, also called Hovevei Tsiyon) movement, founded at a conference held in the city of Katowice, drew members from across Eastern Europe. Leon Pinsker, the author of the influential pamphlet Autoemancipation, was chosen to chair Hibat Tsiyon's central bureau in Odesa, and several agricultural colonies were established in Palestine under his auspices.

Hibat Tsiyon declined by the early 1890s because of internal ideological divides between religious traditionalist and secularist nationalist members, and between those who emphasized agricultural colonies in Palestine as opposed to those who promoted cultural nationalism and Hebrew education in the Diaspora.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, 2010), 363;

- Michael Stanislawski, "Ḥibat Tsiyon," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010);

- Michael Stanislawski, "Russia: Russian Empire," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1897–1907

Jewish national autonomism

In 1897, the year of the formation of the world Zionist movement and the populist socialist General Jewish Workers Alliance (the Bund), the historian Simon Dubnow (based in Odesa since 1890) began to publish a series of essays setting out his position on 'national autonomism.' In his view, Jews did not require a physical homeland outside Europe to become a nation because they already were a (diaspora) nation: "all sections of the Jewish people, though divided in their political allegiance, form one spiritual or historico-cultural nation." What Jews needed was to modernize their communal institutions and gain constitutional recognition in a multinational state as a fully legitimate national minority.

Read more...

Dubnow regarded Zionism as an illusory solution to the vast problems of the Eastern European Jewish masses. He also rejected socialism, especially the Marxist version, because it overemphasized the struggle of the working class against the bourgeoisie when it was the Jewish people as a whole that was under antisemitic attack. In 1907, Dubnow helped found the small political Folkish party (Folkspartei) on a platform that called for "the institutionalization of autonomy through self-governing local and federated community councils" of a national rather than religious character.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) II, 28–29, 64;

- Robert M. Seltzer, "Dubnow, Simon," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1897–1905

The Bund and national cultural autonomy

A small group of Vilna Jews, influenced by Marxist ideas, founded a Jewish socialist political party in 1897 — the General Jewish Workers Alliance, known simply as the Bund — to represent the interests of Jewish workers across the Russian Empire. Within less than a decade, the Bund became the largest and best-organized Jewish political party in Eastern Europe.

Read more...

The Bund considered itself part of the Russian social-democratic movement. It was an autonomous member of the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party (RSDWP) until 1903, when it seceded from the RSDWP due to increasingly diverging perspectives. As described by a founder of the Bund, Arkady Kremer, the Bund's goal was "not only the struggle for general Russian political demands; it will also have the special task of defending the interests of the Jewish workers, of carrying on the struggle for their civil rights, and, above all, of combating the discriminatory anti-Jewish laws."

The Bund passed a resolution in 1901 endorsing "a federation of nationalities with full national autonomy for each [including for the Jewish people], regardless of the territory it occupies…." In 1905 the Bund came out clearly in favour of 'national-cultural autonomy' — the transfer of jurisdiction over culture, education, and domestic law to institutions democratically elected by the various national minorities. Such autonomy, by its very nature, was to be sustained by a national language, and in the Bund's view, the national language of Jews was Yiddish (rather than Hebrew).

The focus on Yiddish in part explains the Bund's mass appeal. Tens of thousands of Jewish workers and students in the Pale of Settlement and Congress Poland responded to the Bund's call to join mass demonstrations during the revolutionary year of 1905. At the time, the Bund claimed 34,000 members in 274 branches, with a strong presence in Ukraine (though it was strongest in Lithuania and Belarus and parts of Congress Poland).

The Bund played a significant role in the organization of Jewish self-defence during the 1903–1906 pogroms. It also cultivated close cooperation with non-Jewish Ukrainian political parties that shared its goals, both in the Russian Empire and Austria-Hungary.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) II, 33–34;

- Shmuel Ettinger, "The Modern Period," in A History of the Jewish People, H.H. Ben Sasson (Cambridge, Mass., 1976), 910–911;

- Daniel Blatman, "Bund," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1897–1908

Ukrainian cultural/political activism

A clandestine Ukrainian cultural organization, the General Ukrainian Non-Party Democratic Organization, was founded in Kyiv in 1897 on the initiative of two scholars, Oleksandr Konysky and Volodymyr Antonovych. Many of the early members also belonged to the Kyiv hromada or other hromadas (clandestine Ukrainian cultural societies). Initially, the organization was mainly devoted to publishing. However, by the early 1900s, it became more political as members agitated for the use of the Ukrainian language in schools.

Read more...

In 1904, the organization changed its name to the Ukrainian Democratic Party and adopted a full political program. It demanded national autonomy for Ukrainians and other nationalities within a federated Russia and radical economic and social reforms. A year later, it merged with the Ukrainian Radical Party to form the Ukrainian Democratic Radical Party (UDRP), a liberal nationalist political party consisting primarily of members of the intelligentsia who were active in the Prosvita societies and the co-operative movement. In early 1908, the UDRP, many of whose members also belonged to the Russian Constitutional Democratic (Kadet) Party, fell apart; most of its members joined the clandestine Society of Ukrainian Progressives, which in 1917 became the Ukrainian Party of Socialist Federalists.

sources and related

- Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine, entries for "Konysky, Oleksander," "Hromadas," "Hromada of Kyiv," "Ukrainian Democratic Radical party," and "Constitutional Democratic (kadet) party."

Related

Chapter 6.1 1850s–1905

1899

Moshe Leib Lilienblum's second autobiography, Derekh teshuvah (The Path of Repentance), was published —a work that shaped the historiography of Jews in the modern period and understanding of their interactions with the broader society. This autobiography retained elements of Lilienblum's 1873 autobiography, which recorded his transition from exclusive study of Jewish religious texts to becoming a maskil (proponent of the Jewish enlightenment) to engagement with Russian radicalism while also embracing the newly emerging Jewish national movement. Like other Jewish intellectuals after the pogroms of the early 1880s, Lilienblum lost faith in the possibility of integration within Russian society. He now subscribed to the view that antisemitism was too deeply rooted in the nations where Jews lived, that the higher Jews rose on the social and economic ladder, the more their security would be at risk. His conclusion: the only way to rectify the situation of Jewish vulnerability was to gather Jews in a territory where they would form the majority.

sources

- Israel Bartal "Lilienblum, Mosheh Leib," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1905–1907

Labour Zionism

Ber Borokhov founded the Po'alei Tsiyon party (Jewish Social Democratic Workers Party), which combined socialism and Zionism and considered Yiddish a Jewish national language alongside Hebrew. These features enabled Po'alei Tsiyon to compete effectively with the Bund. When Borokhov founded the Zionist Socialist Workers Union in Katerynoslav (now Dnipro, Ukraine) in 1901, he faced opposition from both the Russian Social Democrats and the Zionists. He won over the former group through his sophisticated writings on the concept of productivity of one's labour and the role of the working classes. He gained support from the latter group by advancing the idea that the shift to a normal productive life could only take place in the historic homeland, the Land of Israel. Borokhov's formulation of these ideas enabled many to feel comfortable supporting both socialism and Zionism and inspired them to join the party.

Read more...

Po'alei Tsiyon set up its World Alliance in 1907, with branches in Austria, North and South America, Great Britain, Palestine, and Russia. Though differences soon surfaced among the various branches of the movement, Po'alei Tsiyon nonetheless became a distinct and important segment within international Zionism.

sources

- Samuel Kassow, "Po'ale Tsiyon," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010);

- Dovid Katz, "Borokhov, Ber," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1905–1907

Revolution and pogroms in the Russian Empire

The revolution that shook the Russian Empire in 1905 spawned workers' strikes and peasant unrest across Ukraine, leading to radical reforms that benefitted both Ukrainians and Jews. However, extremist Russian nationalists blamed Jews for the unrest and instigated a wave of widespread pogroms.

Read more...

In response to the revolutionary unrest, Tsar Nicholas II issued a manifesto on October 30, 1905, which offered a range of political concessions. The creation of legal, political parties became possible for both Ukrainians and Jews, enabling them to participate in the limited parliament, the State Duma. Lifting the prohibition on the use of the Ukrainian language and assurances regarding freedom of the press led to a proliferation of Ukrainian newspapers and voluntary associations in late 1905–1906. The October Manifesto also led to the elimination of many laws restricting the participation of Jews in Russian civic life, enabling them to vote in elections to the new parliament. In effect, Jews gained political rights before they were legally emancipated.

The revolutionary upheaval, however, also led to the rise of reactionary Russian nationalism. Even though the number of Jews among the revolutionary activists had declined considerably, conservative supporters of the monarchy associated Jews in general with the revolution. More extremist elements actively propagated antisemitic conspiracy theories and incited pogroms.

sources

- John-Paul Himka, "Revolution of 1905," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1993);

- Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe (New York, 2015), 190–191;

- Michael Stanislawski, "Russia: Russian Empire," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1906

In Kyiv, an unofficial communal body dominated by the Brodsky family began to function and gained recognition from the municipality as the "Jewish Representation for Charitable Affairs."

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) II, 193.

1906–1912

Mykhailo Hrushevsky, the preeminent Ukrainian historian who had devoted over a decade as a leader of the Ukrainian national and cultural movement in Galicia, became actively engaged in fostering a Ukrainian national and cultural revival in the Russian Empire. During a brief stay (1906) in St. Petersburg, he assisted the newly formed Ukrainian Club there as editor of its publication and served as an advisor to the Ukrainian deputies. He then transferred to Kyiv, where he co-founded the Ukrainian Scientific Society (modelled on the Shevchenko Scientific Society in Galicia), serving as its first head and co-editor of its journals.

Read more...

To foster Ukrainian national consciousness more widely, Hrushevsky founded and published the popular newspaper Selo (1909–11); when this was closed down by the Russian government, he established Zasiv(1911–12). In 1908, Hrushevsky was one of the founding members of the Society of Ukrainian Progressives, emerging as the universally acknowledged leader of the Ukrainian movement. His stated goal at this time was a democratic and autonomous Ukraine within a democratic federal Russian state, with equal treatment of the various national-ethnic groups. In 1917 Hrushevsky was elected chairman of the Central Council (Rada) of the Ukrainian National Republic.

sources and related

- Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe (New York, 2015), 195;

- Oleksander Ohloblyn and Lubomyr Wynar, "Mykhailo Hrushevsky," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1989).

Related

Chapter 6.4 1898–1911

1911

Pyotr Stolypin, the Russian prime minister who had promoted the removal of some legal restrictions for Jews while introducing others, was assassinated in Kyiv. The assassin was Dmitry Bogrov, the son of a Jewish convert to Christianity and member of an anarcho-communist group.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) II, 67–68.

![[sp_easyaccordion id="5238"]](https://ujetimeline.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/06-032_Katowice_Conference._P._Krause._1884_Eng-1200x753.jpg)