1840s–1890s

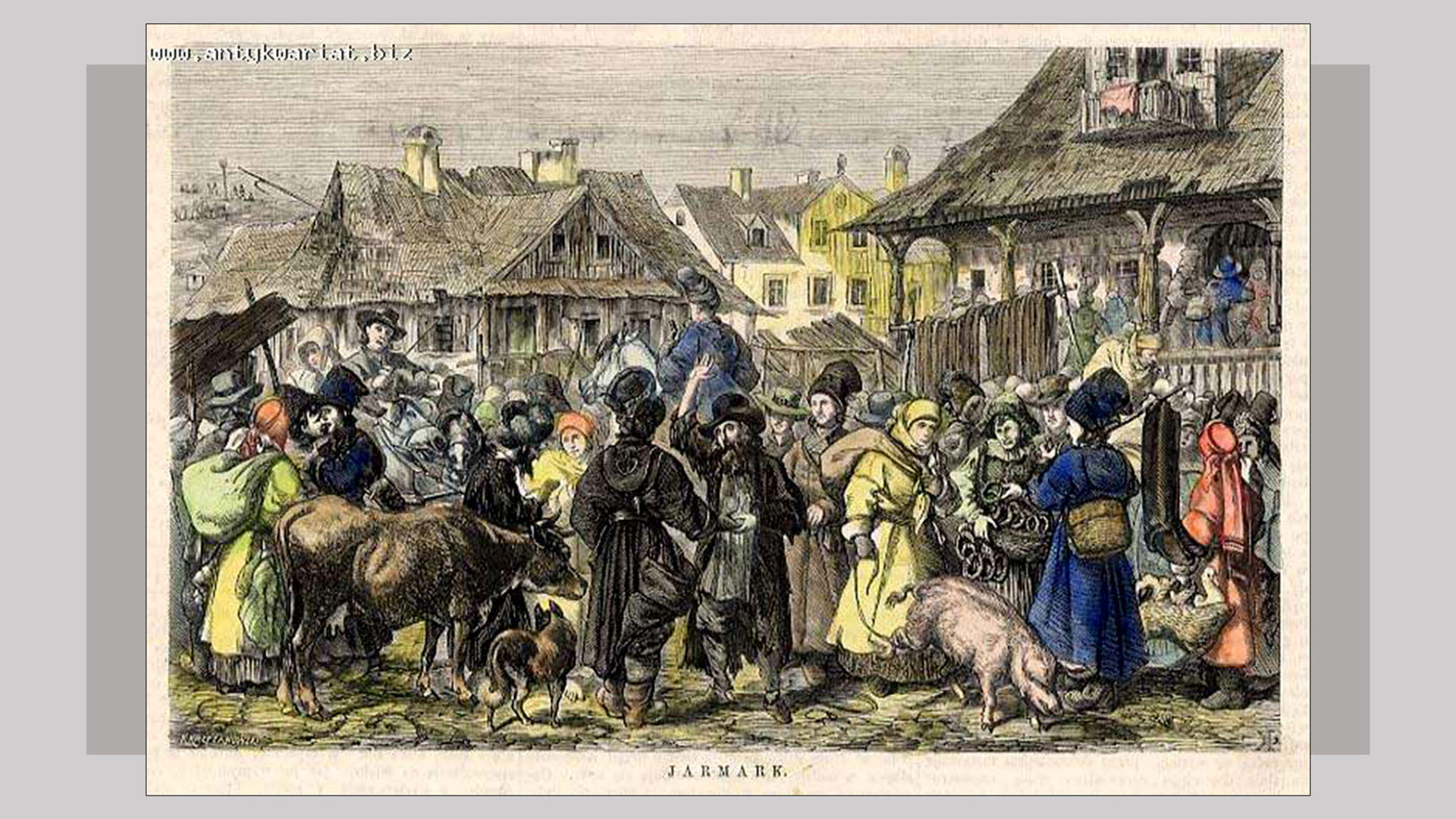

The marketplace and the tavern

Alongside the marketplace, the tavern/korchma was a key meeting place for Jews and Ukrainians. "In Jewish-owned taverns, customers were not only able to eat, smoke, dance, and drink, they also discussed business, looked for jobs, cut deals, traded in commodities, engaged in match-making, changed and fed horses, repaired wagons, borrowed money, relaxed on their way to a fair, and shared news. In essence, taverns functioned as social clubs.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence (Toronto, Second Edition, 2018), 88.

1846–1848

Peasants and landlords

During the revolutions of 1846–48, there was much less anti-Jewish violence in Galicia than in other areas of Europe. The main antagonism in the province was between landlords and peasants. When several Polish gentry activists in Galicia proclaimed a revolution against Austrian rule in 1846 and tried to win over the Polish peasantry to their cause by promising the abolition of serfdom, the mistrustful peasants instead turned on the gentry estate owners and massacred them. Austrian soldiers eventually put down the uprising, but not before the peasants had effectively eliminated the latest attempt at a Polish anti-Austrian revolt.

Unlike the landlords, the local Jews enjoyed a degree of trust in the villages at this time, as illustrated in an appeal to Jews in the countryside, made in a Yiddish pamphlet issued in Lviv: "Your words are listened to by peasants… you should therefore see to it that there is peace between the lords and the peasants."

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. I, 264;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 433;

- John-Paul Himka, Galician Villagers and the Ukrainian National Movement in the Nineteenth Century (Macmillan Press, 1988), 24, 30.

1848–1860s

The Galician triangle

Galicia was the setting for "the Polish-Ukrainian-Jewish triangle," as the three nationalities entered the political arena with conflicting agendas. Many Galician Jewish leaders engaged with the political struggle, often aligning themselves with the Poles. Other Jewish leaders distanced themselves from Polish national aspirations and adopted a pro-Austrian position they believed would increase their prospects for civil rights and protection from anti-Jewish violence.

Read more...

Resenting the identification of Jewish leaders with the Polish cause, the emerging Ukrainian political leadership in Galicia — the Supreme Ruthenian Council — declared itself (in June 1848) unequivocally against the emancipation of the Jews. This attitude on the part of the Ukrainian leadership alienated acculturated Jews, then petitioning the Austrian regime for legal equality and civil rights.

The tendency of Jews to ally themselves with Poles may be considered a pragmatic choice for a small, vulnerable minority in a region where the Poles, especially after 1867, were the dominant element politically, culturally, and socially. In the late 1890s, however, Polish antisemitism and a wave of anti-Jewish violence, perpetrated mostly by Polish peasants, undermined prospects for Polish-Jewish cooperation.

On a positive note, historian John-Paul Himka observed that the antagonisms between the three groups during this period were "growing pains" in the sense that their interactions resulted from progressive, mostly beneficial developments — including the abolition of serfdom, universal male suffrage, increased civic rights, and economic modernization. These reforms strengthened the capacity of each group to pursue their respective interests. Moreover, there were signs that the three were starting to work out a modus vivendi, for example, in the Polish-Ukrainian compromise advanced by Metropolitan Sheptytsky in 1914 and the Ukrainian-Jewish rapprochement that led to cooperation in the Western Ukrainian National Republic in 1917.

sources and related

- Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 434–440;

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. I, 265–267;

- John-Paul Himka, "Dimensions of a Triangle: Polish-Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Austrian Galicia," Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry, vol. 12, Israel Bartal & Antony Polonsky, eds. (London/Portland, 1999), 34–36, 48.

Related

Chapter 5.3 1772–1815 (Read More)

1873

A noteworthy Ukrainian-Jewish political alliance materialized in Lviv during the first elections to the Austrian Reichsrat, held in November 1873. An electoral reform law had come into effect in April that year, after considerable debate, reflecting the principles of the 1867 constitution. Ukrainian/Ruthenian and Jewish political leaders embraced the law. Polish politicians, for their part, saw it as a threat to Polish hegemony in Galicia because it enabled free political expression and empowered the province's other minorities. They were especially concerned about their status in eastern Galicia, where Ruthenians were the majority and in urban centers that had high concentrations of Jews.

Read more...

In preparation for the elections, Lviv's Jewish leaders formed a central electoral committee. The motivating force of the committee was the modernist Jewish faction Shomer Yisrael (Guardian of Israel), formed in 1868 with the aim of educating the Jewish population about its rights and obligations under the 1867 constitution. The Jewish leaders realized that they had to find political partners to succeed in the parliamentary elections. The most natural candidate was the Rada Ruska (Ruthenian Council), founded in 1870 with the primary aim of defending the rights of the Ruthenian people. The Ruthenian and Jewish leaders shared the desire to limit Polish domination of the cultural, legislative, and educational arrangements. They were equally inspired by the constitution's fundamental principle of equal rights regardless of religion or nationality. The mutually beneficial agreement reached was that the committee would encourage Jews residing in villages to support Ruthenian candidates in exchange for urban Ruthenian support for Jewish candidates.

The alliance was supported by a number of Jewish communities in East Galicia. However, because the Shomer Yisrael and the Holovna ruska rada were associated with the integrationist policies of Austrian liberals, the alliance did not have the support of the Greek Catholic priests (who in turn influenced their parishioners); nor did it have the support of the more traditionally orthodox Jewish circles.

The results of the 1873 elections were a mixed blessing for the Ruthenian-Jewish alliance. Fifteen of twenty-seven seats from rural districts went to Ruthenian candidates, mostly priests; only three of the thirteen urban seats went to Jewish candidates. The Jewish leaders attributed their poor results to the failure of the Ruthenians to vote en masse for the Jewish candidates and the questionable election practices of the Poles, which included bribing Ruthenian farmers with food, drink, and cash. Also, not all Jews opposed the Poles, and some feared violent Polish reprisals if they supported the Ruthenian-Jewish alliance. In fact, severe economic sanctions against Jews followed the elections.

The next election to Parliament in 1879 saw the emergence of a well-organized Orthodox Jewish party that forced a new political alliance with Polish conservatives.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. II, 120–121;

- Rachel Manekin, "Politics, Religion, and National Identity: The Galician Jewish Vote in the 1873 Parliamentary Elections," Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry, vol. 12, Israel Bartal & Antony Polonsky, eds. (London/Portland, 1999),103–105, 111–118.

1870s–1890s

Cross-cultural interaction

The "Galician triangle" also played out in the cultural domain. While socioeconomic, political, and religious differences sharply divided Galicia's Poles, Ukrainians, and Jews during this period, culture played a more ambivalent role. On the one hand, it divided the three nationalities, as each had its own cultural universe. On the other hand, there was a constant process of mutual borrowing and influences across the three cultures, encouraged by centuries of cohabitation.

Read more...

The trend for the Ruthenian national elite in the first half of the nineteenth century was to assimilate into the linguistically-related Polish culture. All-Galician cultural institutions, such as the University of Lviv and the opera, had a largely Polish character. The modernized Jewish educated elite identified first with linguistically-related German culture and then with Polish culture. Only toward the end of the nineteenth century were attempts made to create a modern Jewish cultural sphere, in conjunction with the emergence of modern Jewish nationalist politics. By then, segments of the three groups also found new common cultural ground as a result of Austrianization and Europeanization.

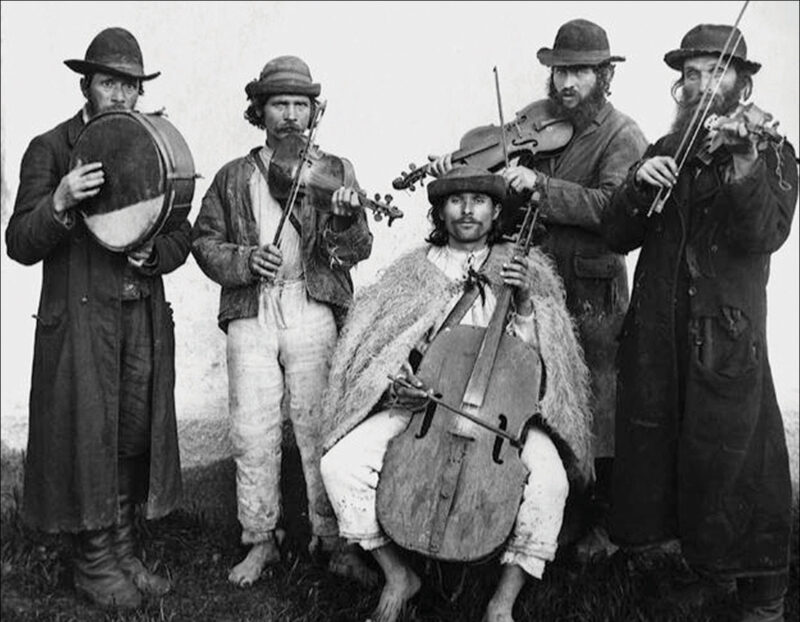

In Transcarpathia, similar socioeconomic status and patterns of religiosity fostered mutual respect and empathy between Jews and their Ukrainian neighbours. Mutual empathy was expressed also in cultural interaction, especially in the realm of language and music. Aside from their native Yiddish, Transcarpathian Jews communicated fluently in spoken Ukrainian; and local klezmer bands engaged both Jewish and Ukrainian musicians.

sources

- John-Paul Himka, "Dimensions of a Triangle: Polish-Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Austrian Galicia," Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry, vol. 12, Israel Bartal & Antony Polonsky, eds. (London/Portland, 1999), 44–46;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Jews in Transcarpathia: A Brief Historical Outline (Carpatho-Rusyn Research Center, 2005).

1883–1912

Ivan Franko's views on Jews

Ivan Franko's views regarding Jews evolved over this period. As described by historian Yaroslav Hrytsak, "Franko's writings may be read sometimes as philosemitic, sometimes as antisemitic." His 1883 article "Pytannia zhydivske" (The Jewish Question), published as a front-page editorial in the Lviv newspaper Dilo, contained stock antisemitic, Marxist-inspired themes then current in some European intellectual circles. He attributed the recent pogroms in tsarist Russia to the "demoralizing dominance of Jewish capital and exploitation," suggesting that Jews themselves had provoked the pogroms for their own monetary advantage, as they received compensation for material losses from the government and Jewish relief organizations. Themes of Jews as exploiters also coloured Franko's Boryslav stories (1876–82) and Boa constrictor (1884), while the poem Shvyndelesa (1884) about a devious Jewish tavernkeeper featured common negative stereotypes.

Read more...

In response to accusations of antisemitism, Franko penned the article "Semityzm I antysemityzm v Halychyni" (Semitism and antisemitism in Galicia) in 1887, in which he remained preoccupied with the prominent role of Jews in the Galician economy. At the same time, however, he was exploring reasoned solutions, such as broad, structural economic reforms. He also presented options for Jews, including voluntary assimilation, emigration to a country where they could develop as a self-determining people, or remaining in Galicia "with the rights of foreigners." Franko rejected the feasibility of Jewish assimilation in both the religious or national sense, in effect recognizing Jews as a separate nation. (It is noteworthy that Franko's views on options for Jews reflected those advocated at the time by the young Polish-Jewish intellectual Alfred Nossig).

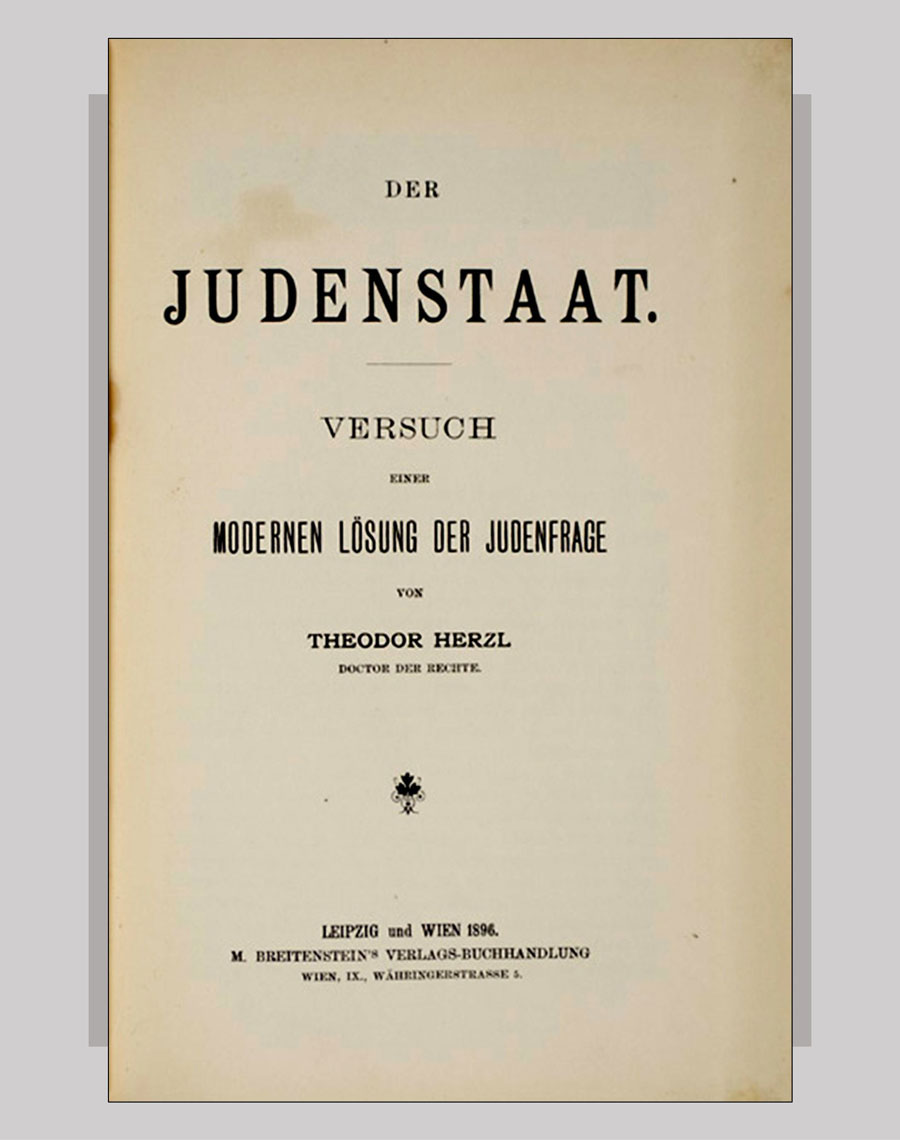

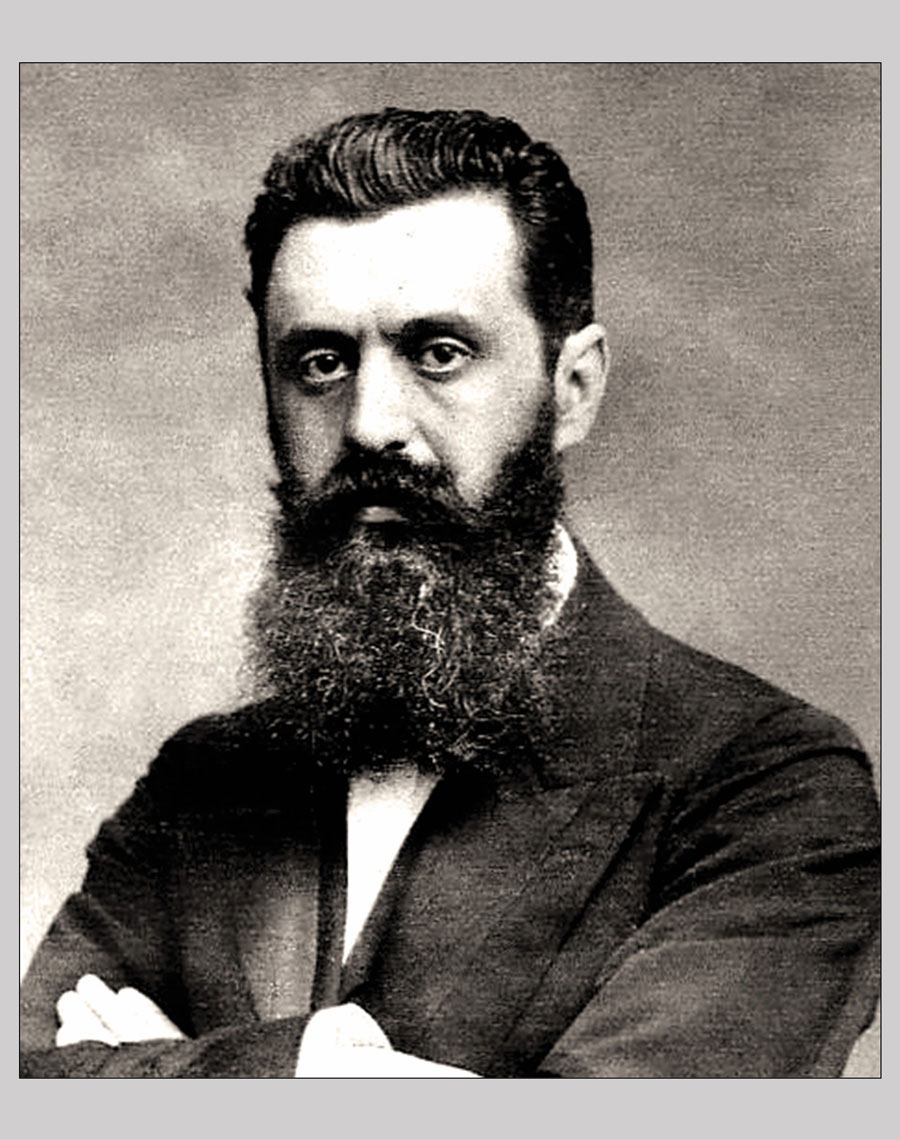

Yaroslav Hrytsak observed that Franko's views evolved, with a sharp decrease in antisemitic elements as he transitioned from socialism to embracing Ukrainian nationalism in the mid-1890s. In a review of Theodor Herzl's Judenstaat (The Jewish State, the foundational text of Zionism), Franko lauded Herzl's vision but doubted the possibility of realizing it. In Franko's view, the more realistic and immediate solution for Jews was neither assimilation nor flight, but rather solidarity with Ukrainian aspirations — a theme advanced in Franko's 1900 novel, Perekhresni stezhky (Crossroads). Yet, as articulated in the second edition of his novel Petrii i Dovbushchuky (1875, 1912), the two protagonists who seek solidarity between the two communities meet with frustration. They find that the Jewish community remains entangled in an economically unequal relationship with Ukrainians, while many Ukrainians are ruled by prejudice, ignorance, and violence.

Franko was familiar with Jewish culture and customs, living in proximity with Jews and Jewish friends since childhood. He mastered Yiddish and Hebrew, translated Jewish poets from Yiddish, and supported Jewish poets who wrote in Ukrainian. The evolution of his own views and his compilation of Galician Ruthenian proverbs (published 1901–1910) gave him insight into the nature and extent of Judeophobic stereotypes then prevalent in Galician society. Considering Franko's writings and public stance in the last two decades of his career, Yaroslav Hrytsak concludes that "antisemitism constituted neither the nucleus of his views on the Jewish question nor his world perception: it was negated by his other declarations and political steps."

sources

- Myroslav Shkandrij, Jews in Ukrainian Literature. Representation and Identity (New Haven, 2009), 69–80;

- Yaroslav Hrytsak, "A Strange Case of Antisemitism," in Omer Bartov and Eric D. Weitz, Shatterzone of Empires (Bloomington, Indiana, 2013), 228, 231, 237;

- Yaroslav Hrytsak, Ivan Franko and His Community (Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, 2018), 302, 308–315, 318.

1898–1912

An interethnic project

An interethnic team carried out the construction of the Israelite Hospital in Lviv — a hospital that then served the city's multiethnic population. Built in 1898–1903 on a plot that had been in Jewish hands for five centuries, the hospital served Jews and non-Jews alike. As documented by architectural historian Sergey Kravtsov, the initiative and funding came from the Jewish philanthropist Maurycy Lazarus; the contractor hired was the firm of Ivan Levynsky — a Ukrainian patriot and an outstanding architect who also worked on Lviv's opera house and the new railway station; and the project design was prepared by Levynsky's Polish employee Kazimierz Mokłowski, an ethnographer, architectural historian, and member of the Social Democratic Party of Galicia. A new wing was commissioned in 1912 from the architectural firm of Michał Ulam, son-in-law of the Progressive Chief Rabbi of Lviv.

sources

- Sergey Kravtsov, "The Israelite Hospital of Lemberg/Lwów/Lviv, 1898–1912: 'Jewish' Architecture, by an 'International' Team," in Wolf Moskovich and Alti Rodal, editors, The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter: Cultural Dimensions, Volume 25 of Jews and Slavs (Jerusalem: Hebrew University of Jerusalem, "Philobiblon" 2016).

1905–1907

Ukrainian-Jewish political cooperation

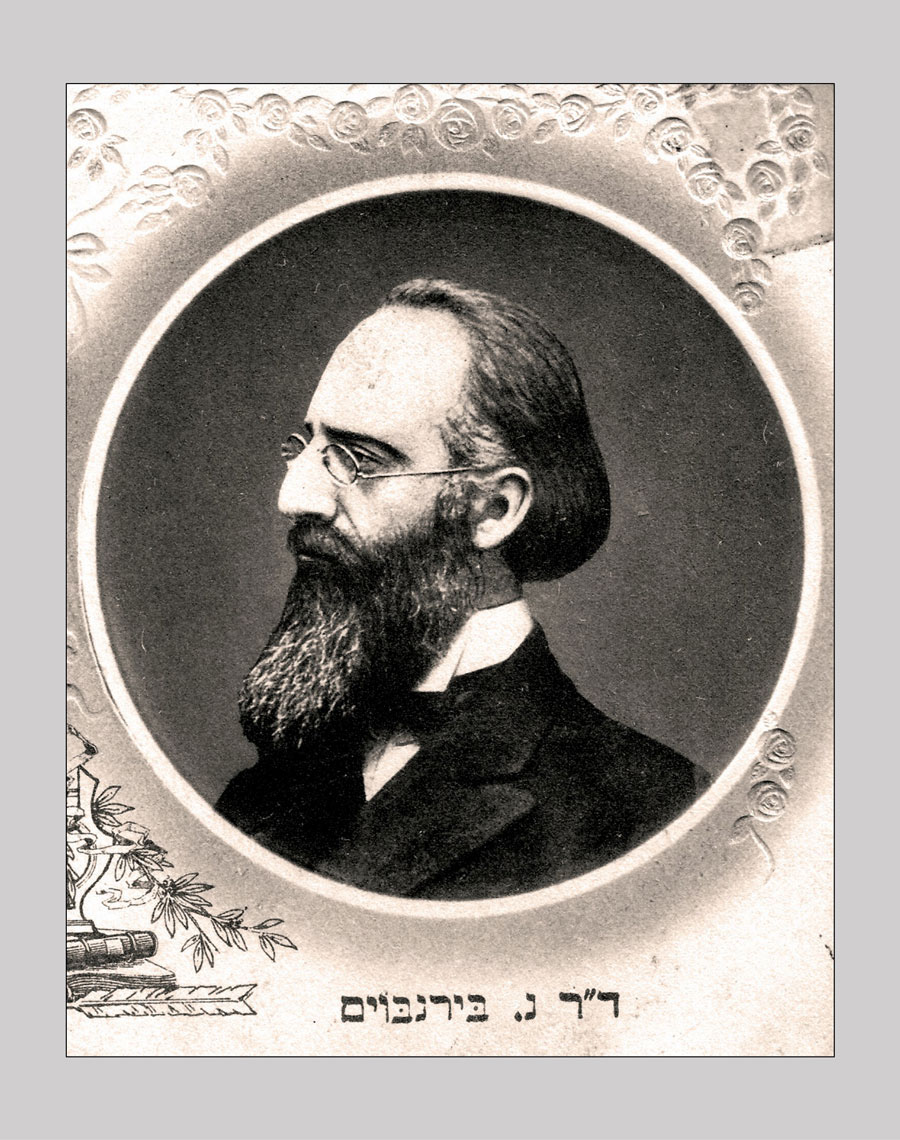

Ukrainian and Jewish national activists in Austrian Galicia forged a political alliance in 1907, during Austria's first parliamentary elections under universal male suffrage. Initially, the Galician delegation at the Austrian Zionist conference had argued that an alliance with the Ukrainians against the Poles should be avoided since it would lead to severe economic reprisals against Jews. However, when Yuliian Romanchuk, the leader of the Ukrainian Club, eloquently endorsed the formation of a separate Jewish electoral constituency, he was supported by Benno Straucher, the Jewish nationalist representative from Czernowitz (Chernivtsi). Later, Nathan Birnbaum, a strong advocate of Jewish national autonomy in Austria-Hungary, publicly thanked Romanchuk for recognizing the Jews as a people in "a modern, non-antisemitic way."

Read more...

Ukrainian nationalists believed that a more nationalist Jewish community would counteract Polish political dominance in Galicia. At the same time, some Zionists saw in the Ukrainian-Jewish alliance the potential to elect Jewish parliamentary representatives in rural Ukrainian districts where they were competing against Polish politicians. The alliance was a qualified success, leading to a more robust national Ukrainian faction and the first Zionist faction in any European parliament. Although not repeated in the 1911 elections, the alliance sparked a pro-Ukrainian discourse in Jewish politics and a pro-Zionist one in Ukrainian politics. It also placed Zionism not only as a reaction to rampant turn-of-the-century racial antisemitism but also in the context of the European-wide national awakenings of the period.

sources

- Joshua Shanes, Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, "An Unlikely Alliance: The 1907 Ukrainian-Jewish Electoral Coalition," Nations and Nationalism 15 (3) (2009): 483–505;

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. II, 139–140.