ca. 650–250 BCE

The Scythians

A land of great beauty and natural riches, Ukraine was frequently overrun by neighbouring peoples that sought to dominate but ultimately came to love the lands north of the Black Sea. Foremost among these ancient migrants were the Scythians, nomadic tribes (believed to be of Iranian origin) who came to rule over the sedentary agriculturalist population in central and eastern Ukraine (ca. 700–250 BCE). Some scholars believe that the sedentary agriculturists of the forest steppes, who were often under attack by a succession of nomad invaders, may have been the predecessors of the Eastern Slavs.

Archaeologists have uncovered artifacts in Ukraine (and neighbouring countries) relating to a large sedentary population that lived in large settlements — the so-called Trypillian civilization (ca. 4500–2250 BCE), famed for its pottery designs, statuettes and mysterious, probably matriarchal religious beliefs. For many Ukrainians, their ancient history begins with an account of this civilization and the implicit understanding that later invasions and migrations intermixed with it but never displaced it.

Among the most ancient other ethnic groups inhabiting present-day Ukraine were Greeks, later joined by Jews. According to the Greek historian Herodotus ("the Father of History," fifth century BCE), the Scythian kingdom was a conglomerate of ethnic groups and cultures whose economic roles were determined by geography and ecology — coast, steppe, and forest. The Scythian polity, centred along the lower Dnieper River and the Crimea steppe hinterland, established a number of hill forts and cities and reached its peak between 350 and 250 BCE.

Read more...

Greeks and Hellenized Scythians who occupied the coast served as intermediaries in trade between the Mediterranean world of Greece and the hinterland. Dwellers of the mixed forest-steppe areas provided the main products for trade — cereals, dried fish, and slaves. Royal Scythians, a small but bellicose minority, which had become the ruling elite, controlled the trade passing through the steppes, retaining most of the proceeds. They were likely the owners of the golden treasures archeologists have found in the mounds of the region.

Scythian nomadic herders of horses, sheep, and cattle also inhabited the steppes. They traded with the merchants of the Greek city-states that flourished during the same period around the Black and Azov seas. By the mid-third century BCE, a new wave of nomadic tribes from the east, the Sarmatians, drove out the Scythian horsemen and ruled the Pontic steppes for half a millennium.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 28–30;

- Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe (New York, 2015), 5–9;

- "Scythians," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1993);

- Dan Shapira, "The First Jews of Ukraine," in Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry, Volume 26, Jews and Ukrainians, eds. Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Antony Polonsky (Oxford, 2014), 66.

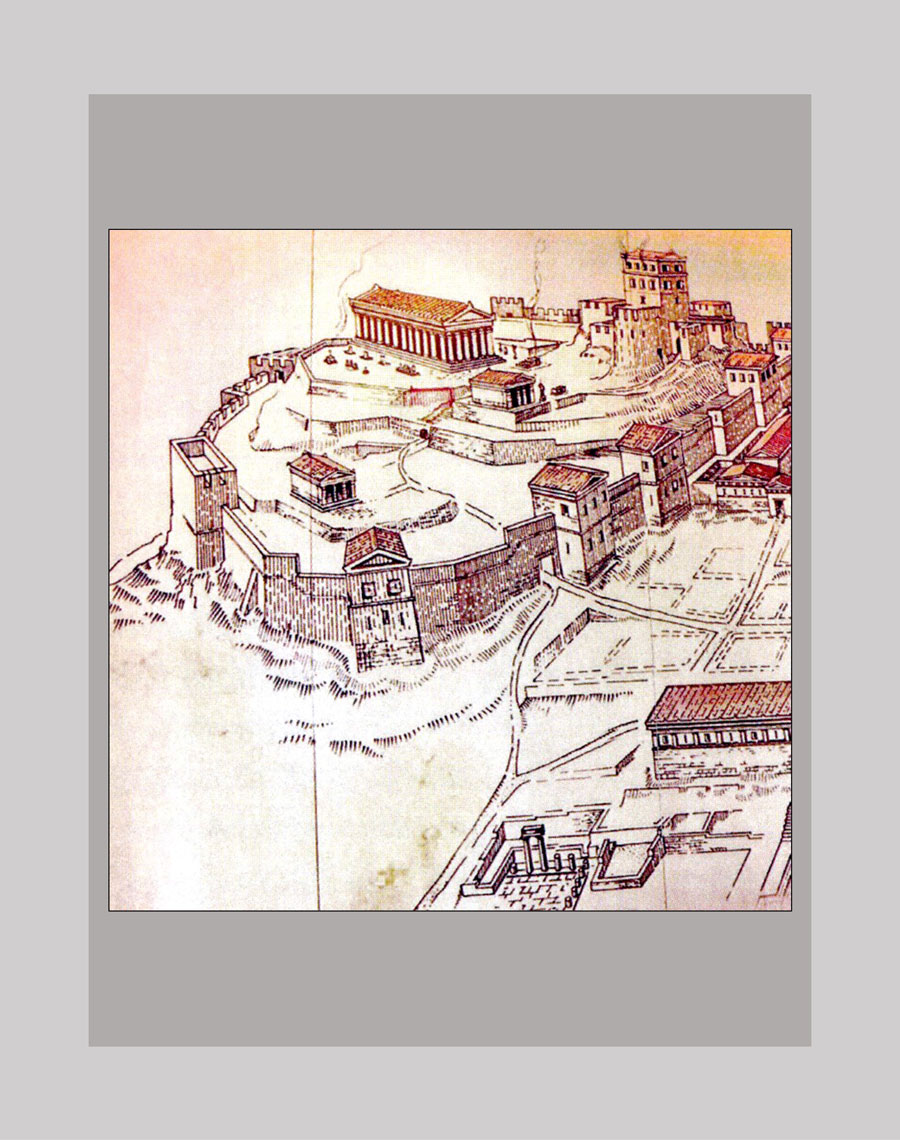

Greek colonies were established (ca. 650–450 BCE) on the shores of the Crimean peninsula and adjacent areas of the Black Sea coast. Most of them were founded by settlers fleeing civil strife in Greece, particularly in Miletus, one of the most powerful states of the era.

Hellenized Greek-speaking Jews and converts to Judaism settled in the Greek colonies around the Black Sea by the first century BCE or earlier. They were likely among the merchants who engaged in trade with the nomadic pastoral tribal peoples in the Ukrainian steppe hinterland.

Read more...

A number of the colonies were strategically located at the mouths of the Dniester, Dnieper, and Southern Buh rivers. As intermediaries in the expanding trade (especially in grain) between the Ukrainian steppe and the Aegean-Mediterranean markets, the colonies gave rise to prosperous city-states. The most important, the Bosporan Kingdom, was a federation of Greek colonies, which lasted for more than four centuries until conquered by the Romans in 63 BCE. It may be considered the first state structure to have existed on Ukrainian lands.

The immigration of Jews to the Crimea was part of the Jewish dispersion in the Hellenistic world. Archaeological finds — including gravestones with Hebrew inscriptions, ruins of synagogues and ritual baths — attest to the presence of Jews in the Greek colony Chersonesus (Sevastopol) in the first century CE and the existence of a traditional organized Jewish community there in the late fourth through early fifth centuries. Before becoming a Christian site in the fifth century CE, the basilica of Chersonesus had served as a synagogue. Significant Jewish communities also emerged in Panticapaeum (present-day Kerch), the capital of the Bosporan Kingdom, and in Olbia, the best known Milesian colony.

At a time when aggressive nomadic tribes from the east continued to ravage the Ukrainian hinterland, the Black Sea coastal cities were revitalized and protected as part of the Byzantine Empire, beginning with the reign of Emperor Justinian (r. 527–565 CE). In Byzantine Chersonesus, however, the state subjected Jews to forced Christianization during this period.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Ukraine: An Illustrated History (Toronto, 2007), 13–16;

- Dan Shapira, "The First Jews of Ukraine," in Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry, Volume 26, Jews and Ukrainians, eds. Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Antony Polonsky (Oxford, 2014), 66–68, 77;

- Michael Toch, "Places of Jewish Settlement in the Byzantine Empire (Map 1)," in The Economic History of European Jews: Late Antiquity and Early Middle Ages (Brill Publishers: Leiden, 2012), 265;

- Mark Kupovetsky, "Population and Migration: Population and Migration before World War I," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

650–960

Khazaria

The Turkic-speaking, originally nomadic Khazars gained control over the sedentary population of the steppe hinterland and conquered nearby tribes. The Khazar elite sought the development of trade and was open to foreign influences. Under the Pax Khazarica (the political order they established), the Khazars fostered stability across a vast region and amassed wealth by controlling trade routes with Central Asia and the Arab world. The arrangement enabled them to collect duties and taxes (through a lord-vassal relationship) from Slavs and other peoples under their hegemony.

The polyethnic and multi-confessional Khazar Kaganate (Empire) provided refuge to at least two waves of Jewish migrants fleeing religious persecution in the Byzantine Empire — in the early 720s and around 930. It was the first polity on the territory of Ukraine to formally incorporate Jews as citizens and to grant them the same civil rights as Christians and Moslems.

Read more...

While many scholars accept that a segment of the Khazar ruling elite may have converted for a brief period to Judaism, speculations that Khazaria was a Jewish state and that Ashkenazi Jews are descendants of the Khazars are generally viewed as unfounded. Nonetheless, the story (or myth) of the conversion of the Khazars to Judaism has captured the imagination of generations of writers. A notable example is the influential classic work The Kuzari, authored by the twelfth-century Spanish-Jewish poet and philosopher Judah Halevi. Intended as a literary philosophical work rather than a historical source, The Kuzari uses the story of the Khazar conversion as a foil for a dialogue about the comparative merits of the three monotheistic religions and a multifaceted defence of Judaism.

Since the early nineteenth century, the so-called "Khazar hypothesis of Ashkenazi ancestry" has generated considerable scholarly and popular debate. It has also served diverse agendas, ranging from advocacy for the integration of Jews into European or Slavic society, to escaping Russian antisemitic regulations and Nazi genocidal policy (in the case of Karaites), to more recent antisemitic and anti-Zionist arguments intent on denying historical links between Ashkenazi Jews and the land of Israel.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 37–38, 45–48;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Ukraine: An Illustrated History (Toronto, 2007), 13–16;

- Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe (New York, 2015), 18;

- Omeljan Pritsak, "The Pre-Ashkenazic Jews of Eastern Europe in relation to the Khazars, the Rus' and the Lithuanians," in Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective, Peter Potichnyj & Howard Aster, eds. (Edmonton, 1988), 6–8;

- Shaul Stampfer, "Did the Khazars Convert to Judaism?" Jewish Social Studies, 19:3 (Indiana University Press, Spring/Summer 2013), 1–72;

- Shaul Stampfer, "Are we All Khazars Now?" Jewish Review of Books (Spring 2014).