ca. 988

After Prince Volodymyr ("the Great") married Anna, sister of Emperor Basil II of Byzantium, he adopted Christianity according to the Eastern Byzantine rite for himself and his realm. Eastern Orthodoxy became the official religion of all the Rus' principalities and ever since has remained the dominant faith in these lands regardless of the regime in power. As a result, the Kyivan realm maintained active cultural and economic ties with the Byzantine Empire.

Interestingly, the description in The Tale of Bygone Years (The Primary Chronicle) of the debate among representatives of the major monotheistic faiths, which led to the conversion of Volodymyr to Eastern Christianity, is remarkably similar to Judah Halevi's account in The Kuzari about the earlier conversion of the Khazar king to Judaism.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 74–78;

- Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe (New York, 2015), 358;

- Henry Abramson, "Ukraine," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

988–1100s

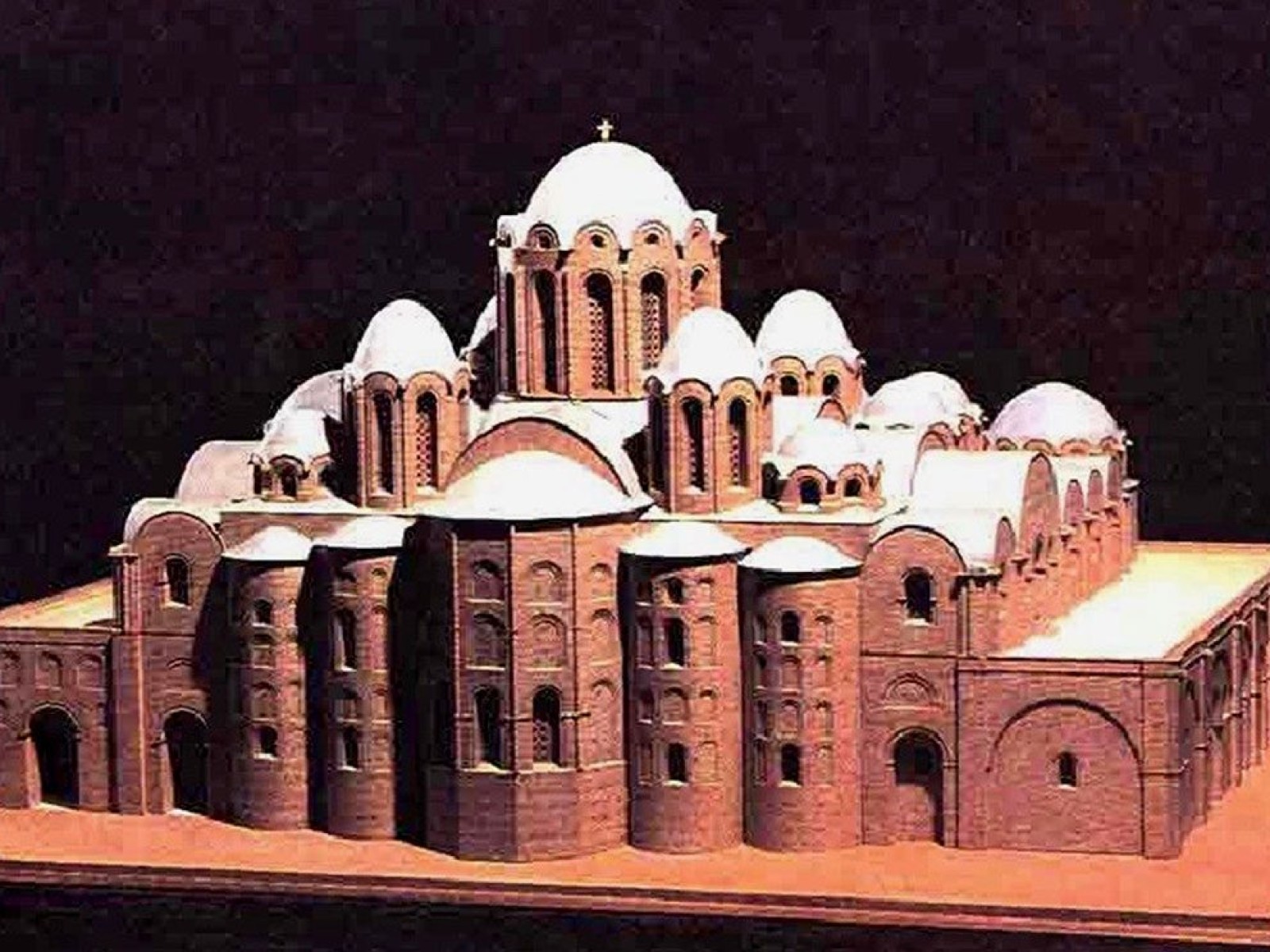

The transition from a pagan nation to a Christian nation brought about a civilizational transformation, including the erection of churches and cathedrals, such as the magnificent St. Sophia Cathedral built in the eleventh century. The Rus' rulers also ushered in an era of intellectual and cultural development by generously founding and funding monasteries, where monks penned chronicles, copied sacred texts, investigated the heavens (both theologically and astronomically), kept libraries, and produced sacral art. Enabling the intellectual awakening and the development of a common culture was the adoption of the Slavic writing system, based on the Bulgarian Old Church Slavonic and features of local Rus' dialects.

sources

- John-Paul Himka, Ten Turning Points: A Brief History of Ukraine.

1000–1100s

Jews in Kyivan Rus' adopted the local East Slavic vernacular language and Slavic personal names. They also created a Judeo-Slavic language called Knaanic (a term derived from "Canaanite"), a fanciful Jewish reference to the ambient culture. According to a Cairo Geniza document, a Rus' Jew arrived in Byzantine Salonica in the eleventh century, who "does not know either the holy tongue [Hebrew] or the Greek tongue, nor does he know Arabic, but [he knows] only the Knaanic language that the people of his native land speak."

Some Kyivan Rus' Jews had knowledge not only of the East Slavic vernacular but also advanced literacy in Church Slavonic — as indicated in several recorded instances of Jews serving as teachers of Slavic literacy in western Europe. As one scholar observed, the linguistic situation reflected in early sources may indicate a peculiar type of coexistence between Jews and their Slavic neighbours, one that is neither extreme isolationism nor extreme assimilation — "a model in which the boundaries between the two groups could take shape along confessional rather than ethno-cultural lines."

sources

- Omeljan Pritsak, "The Pre-Ashkenazic Jews of Eastern Europe in Relation to the Khazars, the Rus' and the Lithuanians," in Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective, Peter Potichnyj & Howard Aster, eds. (Edmonton, 1988), 10;

- Alexander Kulik, "Jews and the Language of Eastern Slavs," The Jewish Quarterly Review, Vol. 104, No. 1 (WINTER 2014), 143.

ca. 1100

The chronicle of events — Povest vremennykh let (The Tale of Bygone Years), also called The Primary Chronicle — incorporated in its broad account of events in Rus' history up to the early twelfth century also key moments of ancient Jewish history since the time of the Biblical flood.

Though widely credited to Nestor, a monk at the Monastery of the Caves in Kyiv, scholars today believe that The Primary Chronicle was compiled either by a group of monks or by a twelfth-century author who drew from unknown annals written in Kyiv in the 11th century. The aim of the chronicle appears to be to inscribe the new Rus' Eastern Christian polity into the holy history of Christianity, from the Old Testament to the advent of Jesus. The chronicle emphasizes the story of the "Apostles to the Slavs" Saints Constantine/Cyril and Methodius, the tenth-century Christianization of Rus', and the rule of the polity's often warring princes. In keeping with the doctrine of supersessionism, it also explains that from the time of Jesus, the role of the chosen people had passed from the Jews to the Christians.

Our knowledge about The Primary Chronicle comes from reworked later versions, as original manuscripts did not survive. Most noteworthy is the fifteenth-century Hypatian Chronicle, whose grand historical narrative supports the idea of political continuity between Kyivan Rus' and the thirteenth-century principality of Galicia-Volhynia, later viewed by some as a proto-Ukrainian state.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence (Toronto, Second Edition, 2018), 163–164;

- Oleksii Tolochko, Povist vremennykh lit, in Entsyklopedia istorii Ukrainy.

1100s–1200s

The writings of eminent medieval rabbis from Western Europe and the Middle East attest to the existence of respected rabbinic scholars and Jewish intellectual activity in Kyivan Rus' during this period. For example, the Hebrew-language "responsa" (compilations of written decisions and rulings in response to questions in Jewish law) of rabbis Samuel ben Eli of Baghdad, Judah ben Kalonymus of Speyer, and Meir of Rothenburg refer to Rabbis Moses of Kyiv, Isa of Chernihiv, and Benjamin ha-Nadiv of Volodymyr. Jewish sources also mention western European Jews who visited Rus'/Ukraine, and Jews from Rus' who went to West European centers of Jewish learning to study and became famous there.

sources

- Omeljan Pritsak, "The Pre-Ashkenazic Jews of Eastern Europe in Relation to the Khazars, the Rus' and the Lithuanians," in Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective, Peter Potichnyj & Howard Aster, eds. (Edmonton, 1988), 9–10;

- Dan Shapira, "The First Jews of Ukraine," in Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry, Volume 26, Jews and Ukrainians, eds. Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Antony Polonsky (Oxford, 2014), 68–69.

1185

The ill-fated military campaign on the steppes south of the Donets' River, led by the Rus' prince Ihor of Chernihiv against the Polovtsians, inspired a famous epic poem, Slovo o polku Ihorevi, (The Lay of Ihor's Campaign), attributed to an anonymous author from the Rus' period.

Scholars today are divided regarding the authenticity of the poem. Most linguists think that it was written during the Kyivan Rus' period. However, several historians consider it to be an eighteenth-century reworking of a fifteenth-century text.

Read more...

In any event, the poem has been regarded as a cornerstone of East Slavic identity — interpreted as a call to unite the scattered Rus' principalities into a single polity that would withstand future threats from the east. Alongside its political message, this epic poem also offers insights into the complex gamut of medieval Rus' social, religious, and family life.

It has been published in numerous editions and languages — including an English version in 1989 by the renowned Russian émigré author Vladimir Nabokov, and a Hebrew version in 1939 (Masa' milhemet Ihor) by the celebrated Hebrew poet Sha'ul Tchernichovsky, native of a village in the southern Ukrainian steppe. This work has inspired later literary versions, including Plach Yaroslavny (Lament of Yaroslavna) by the Ukrainian national bard Taras Shevchenko.

1278

The first testimony about a Karaite presence in the Crimean Peninsula was supplied by the Karaite scholar Aharon ben Yosef, who mentioned a dispute over the calendar between Karaites (those who recognize the religious authority of the Hebrew Bible only) and Rabbinites (those who follow also the rabbinic tradition of Jewish law, as compiled in the Talmud). The dispute took place in Solkhat (Eski Krim), one of the major centers of Karaite settlement, along with Caffa (Feodosiia) and Chufut-Kale.

The Karaites were a Jewish sect that likely came from the Middle East to the Byzantine Empire in the twelfth century and migrated to the Crimean Peninsula in the mid-thirteenth century (not the ninth century, as is suggested in some accounts). In the Crimea, they adopted Turkic speech and eventually developed a distinct Turkic literary language (written in Hebrew script) that was similar to Crimean Tatar.

sources

- Golda Akhiezer, "Karaites," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010);

- Paul Robert Magocsi, This Blessed Land (Toronto 2014), 105–106.