1400s–1500s

The Lithuanian grand dukes left intact the social and legal structure they found in former Kyivan Rus' and superimposed their control over the vast territory in two ways: they recognized the inherited right of both Lithuanian and Rus' princes to the large estates, and made significant land grants to Lithuanian and Rus' boyars (nobles) who supported them in new conquests. These privileges, coupled with a surge in growth of the Baltic grain trade, greatly benefitted the ruling elite, but reinforced serfdom for the vast majority of peasants on Ukrainian lands.

Read more...

Lithuanian society evolved under the influence of the Polish model, giving rise to the following strata: the Grand Duke, nobility (hereditary princes, non-hereditary boyars and gentry), clergy, townspeople (merchants, artisans, unskilled labourers), Jews (merchants, artisans, tradespeople), and peasants (tenant farmers, proprietary serfs).

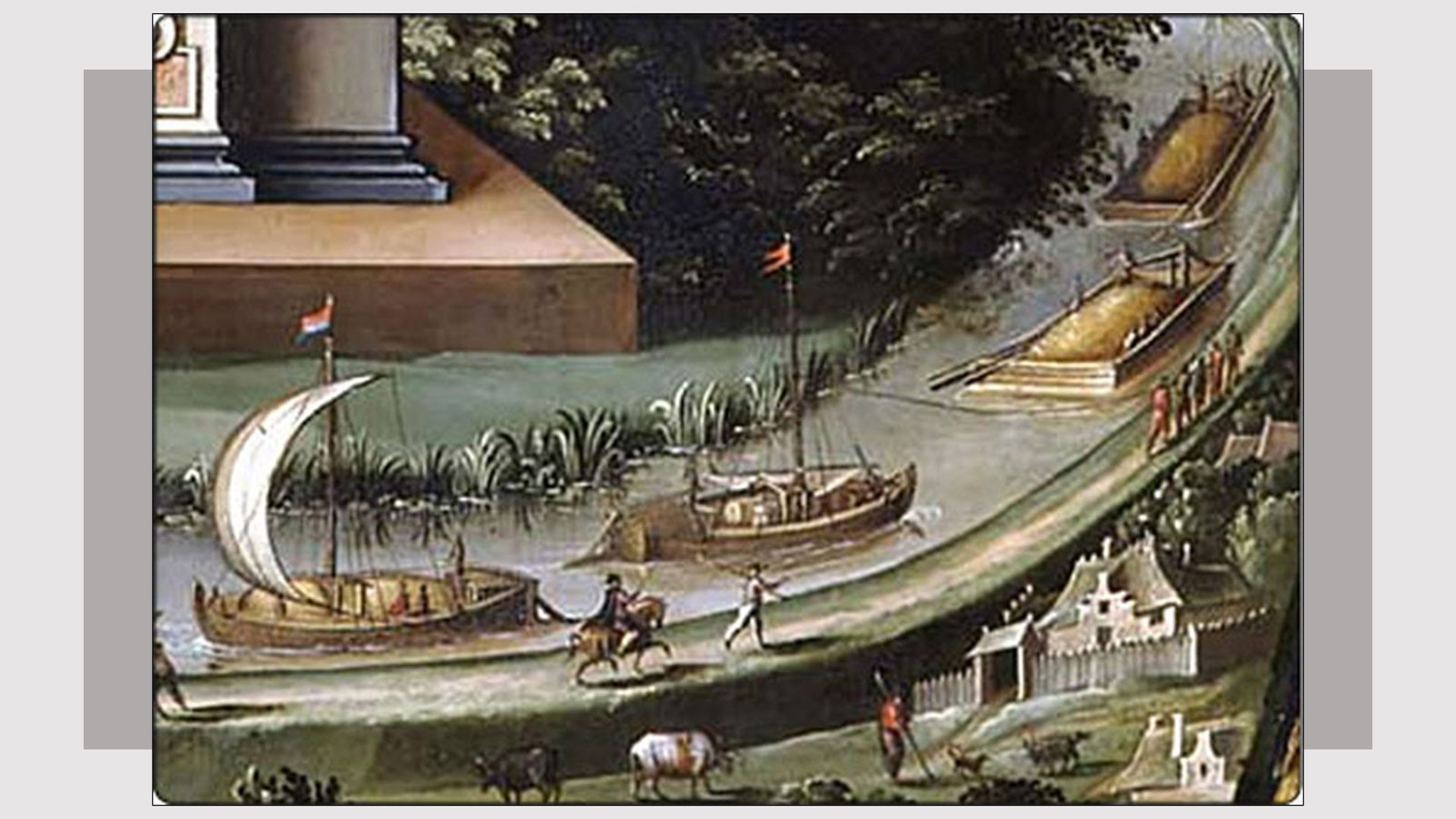

In Poland, the King held the power to distribute high-status positions. The Polish nobility (szlachta) included the magnates, who held the greatest wealth and prestige, and the gentry, who were equal to the magnates in legal status if not in influence or wealth. The nobles were granted special privileges in exchange for their role as defenders of the realm against foreign invasion. The range of their privileges increased during this period not only vis-à-vis the crown but also the church, the townspeople, and especially the peasants. By the sixteenth century, Ukrainian lands became part of a new western European-oriented economic order, at the center of which was the export of grain, primarily from Galicia (Rus') and Volhynia to the Vistula River and Gdansk/Danzig. The growth of the Baltic grain trade increased the Lithuanian and Polish nobility's appetite for more land and greater control over those who toiled on it. As the status of the boyars and gentry was strengthened, that of the peasantry worsened.

Decrees issued by the governments of Poland (between 1496 and 1520) and Lithuania (after 1557) paved the way for the implementation within the next three decades of "neo-serfdom" (or "export-led serfdom"). Agricultural reforms in the Grand Duchy, which included most Ukrainian territory, deprived peasants of property rights to land and placed an increasing number of legal restrictions on their ability to leave the land where they worked. The practice of panshchyna (local term for corvée), whereby a serf was obliged to render unpaid labour, increasingly defined the economic relations between noble landowners and peasants. Peasants were also deprived of access to royal courts; their only recourse when they had complaints about abusive practices was to courts controlled by the nobles themselves. While there were some free peasants and rural labourers on both church and crown lands, the vast majority of peasants had become serfs of the nobility by the sixteenth century.

sources and related

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 137, 144–151;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Ukraine: An Illustrated History (Toronto, Second Edition, 2007), 67–69.

Related

Chapter 4.3 1569–1600s (Read More)

1453

King Casimir IV of Poland re-issued and expanded the charter of Jewish legal rights granted to the Jews by King Bolesław V "the Pious" in 1264. The new charter made more explicit provisions to protect the legal rights of Jewish merchants, reflecting the growing importance of the role of Jews in trade. The Jews in Lithuania had already been granted several privileges in the economic sphere in 1388–1389, including tax-free concessions for their places of worship and burial and the rights to trade, engage in crafts, and own land. By the late fifteenth century, Jews generally could not own land in Poland-Lithuania. They could be leaseholders of rural properties owned by the nobles but not landowners, even in the case of mortgage defaults.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford and Portland, OR, 2010), vol. I, 102;

- Judith Kalik, Movable Inn: The Rural Jewish Population of Minsk Guberniya in 1793-1914 (Berlin, De Gruyter Open Poland, 2018), 23–24.

1550s

At a time when many professions were closed to Jews, some Jews became important in the economic life of medieval Poland and Lithuania as minters, bankers, and moneylenders; many more engaged in trade. In the mid-sixteenth century, the Sejm passed a law prohibiting Jews from minting — a prohibition supported by the Jewish Council of the Lands.

Read more...

Jewish merchants also often engaged in pawnbroking and small-scale moneylending, particularly in smaller towns. Though Jews were by no means the only moneylenders in Poland (and often did not even make up the majority of those making their living this way in any given locale), their activities were singled out for opprobrium. As lenders generally tend to be unpopular, the institutions of Jewish self-government tried to mitigate harmful effects on the community by regulating interest rates. Many Jews turned to trade for their livelihood; some engaged in tax farming, which aroused strong opposition from the nobility, as is clear from a resolution passed by the Sejm in 1538, stipulating that

"those in charge of the collection of our revenues must be without exception members of the landed nobility, professing the Christian faith… we decree that it be unconditionally observed that no Jew be entrusted with the collection of state revenues in any land, for it is unseemly and it runs counter to divine law that such persons be allowed to occupy any position of honour and to exercise any public function among Christian people."

This resolution was largely ignored by the Polish landlords, who continued to hire Jews as tax farmers.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford and Portland, OR, 2010), vol. I, 95–99;

- Salo Baron, A Social and Religious History of the Jews, xvi: Poland-Lithuania 1500–1650 (Philadelphia, 1976) 280;

- Adam Teller, "Economic Life," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1450s–1700s

The Crimean Khanate and the slave trade

While the economic activities of the sedentary segments of the Khanate's population related to agriculture, artisanry, and commerce, the nomadic tribal groups, in particular the Nogay tribes, became prominent actors in the Ottoman Empire's massive slave trade.

Crimean peasant farmers were organized in villages. Village members worked the land in common and paid taxes collectively to a landlord (usually a tribal leader). The landlord did not own peasants; they were free to leave the land if they wished. The most lucrative Crimean agricultural export products were fruit, tobacco, and honey.

Read more...

For the Nogays who pastured their flocks on Ukraine's steppe lands, the most lucrative economic activity was the slave trade. As Islamic law allowed the enslavement only of non-Muslims, the inhabitants of the Christian lands just north of the Nogay steppe (Ukraine and southern Russia) became prime targets. As an Ottoman vassal state, the Crimean Khanate became the primary supplier of slaves for the empire.

Alongside Crimean Tatars, Turks, Arabs, Greeks, Armenians, and others, Jews (especially Karaites, but also Rabbanites) played a role in the slave trade — whether as slaveholders, mediators in ransoming captives, moneylenders, or themselves unfortunate victims of Tatar raids. Some Ashkenazi East European Jews who were ransomed settled among their local redeemers and soon formed one-third of the Crimea's Rabbanite community.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 184–187;

- Dan Shapira, "The First Jews of Ukraine," in Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry, Volume 26, Jews and Ukrainians, eds. Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Antony Polonsky (Oxford, 2014), 72;

- Michael Zand, "Krymchaks," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).