1619

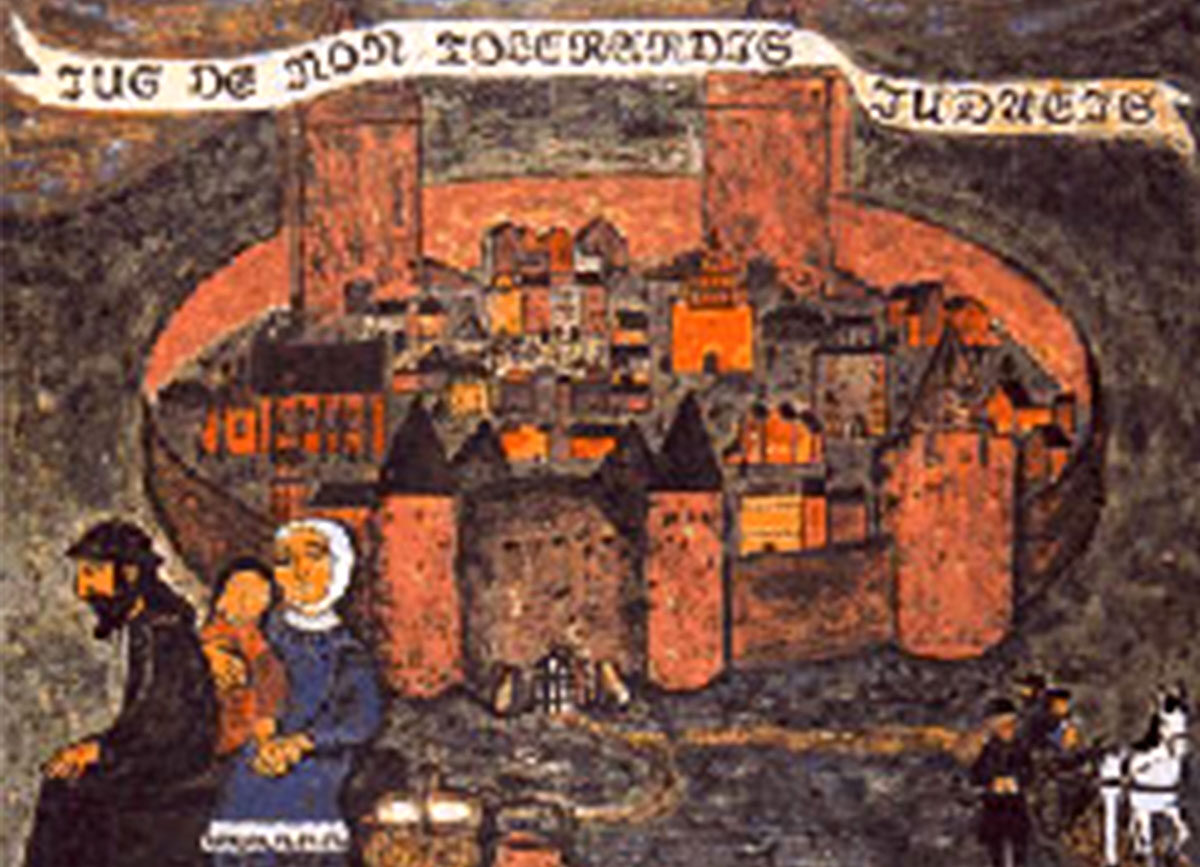

Reacting to the growth of the Jewish population and its economic activity, Christian burghers in Kyiv succeeded in obtaining a royal charter de non tolerandis Judaeis, disallowing Jewish residence and commercial activity in the city.

sources

- Shmuel Ettinger, "Jewish Participation in the Settlement of Ukraine in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries," in Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective, Peter Potichnyj & Howard Aster, eds. (Edmonton, 1988), 29.

1637–1639

The first severe episode of anti-Jewish violence perpetrated by Ukrainian Cossacks occurred during the Pavliuk insurrection, with two hundred Jews reportedly killed. Because many Jews served as middlemen for Polish landlords, Jews, in general, became symbols of oppression and exploitation in the eyes of Ukrainian peasants and their Cossack defenders — and targets for violence during periods of social and political upheaval. In contrast with Jewish experience in western Europe or later in Ukraine, anti-Jewish sentiment during this particular period had a strong socio-economic foundation. Together with other factors, including Christian Judaephobia and social banditry prevalent at the time, socio-economic factors created an atmosphere conducive to anti-Jewish violence on a major scale a decade later.

sources and related

- Jaroslaw Pelenski, "The Cossack Insurrections in Jewish-Ukrainian Relations," in Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective, Peter Potichnyj & Howard Aster, eds. (Edmonton, 1988), 32;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 357–358.

Related

Chapter 4.3 1569–1600s

1648–1649

During a major uprising led by Bohdan Khmelnytsky against the Polish and largely Polonized nobility, marauding peasants, Cossacks and their Tatar allies massacred at least one-third of the estimated 40,000 Jewish people in the region. While eliminating the Jews was not a central aim of the Cossacks, Jews were regarded as part of the enemy camp — and also as candidates for forced conversion to Orthodoxy. Thousands of Jews fled, several thousand were captured for ransom or sale as slaves in the Ottoman Empire, and about 1,000 Jews converted to Christian Orthodoxy under duress. Numerous Jewish communities in Poland-Lithuania were affected, and some were totally destroyed, including in Nemyriv, Tulchyn, and Bar. In some places, the townspeople betrayed Jews to the Cossacks, while in others, such as Lviv, Jews and non-Jews fought together to defend the town. The massacres have loomed prominently in Jewish historical memory as the "gzeyres takh vetat" ("the evil decrees of 1648–49") and figure in Jewish prayer books to this day. The Khmelnytsky uprising is framed very differently in Ukrainian historical memory.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford and Portland, 2010), vol. I, 14, 137;

- Adam Teller and Igor Kakolewski, "Paradisus Iudaeorum, 1569–1648," Polin: 1000 Year History of Polish Jews (Warsaw, 2014), 125;

- Shaul, Stampfer, "Gzeyres Takh Vetat," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1649

In agreements reached with the Russians and the Poles at Zboriv, Khmelnytsky's Cossacks required the expulsion of Jewish leaseholders from Cossack villages. Jews were generally banned from lands under the control of the Cossacks, unless they converted to Christianity.

sources

- Frank E. Sysyn, "The Jewish Factor in the Khmelnytsky Uprising," in Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective, Peter Potichnyj & Howard Aster, eds. (Edmonton, 1988), 50;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 219, 264, 267, 295–6.

1664–1700s

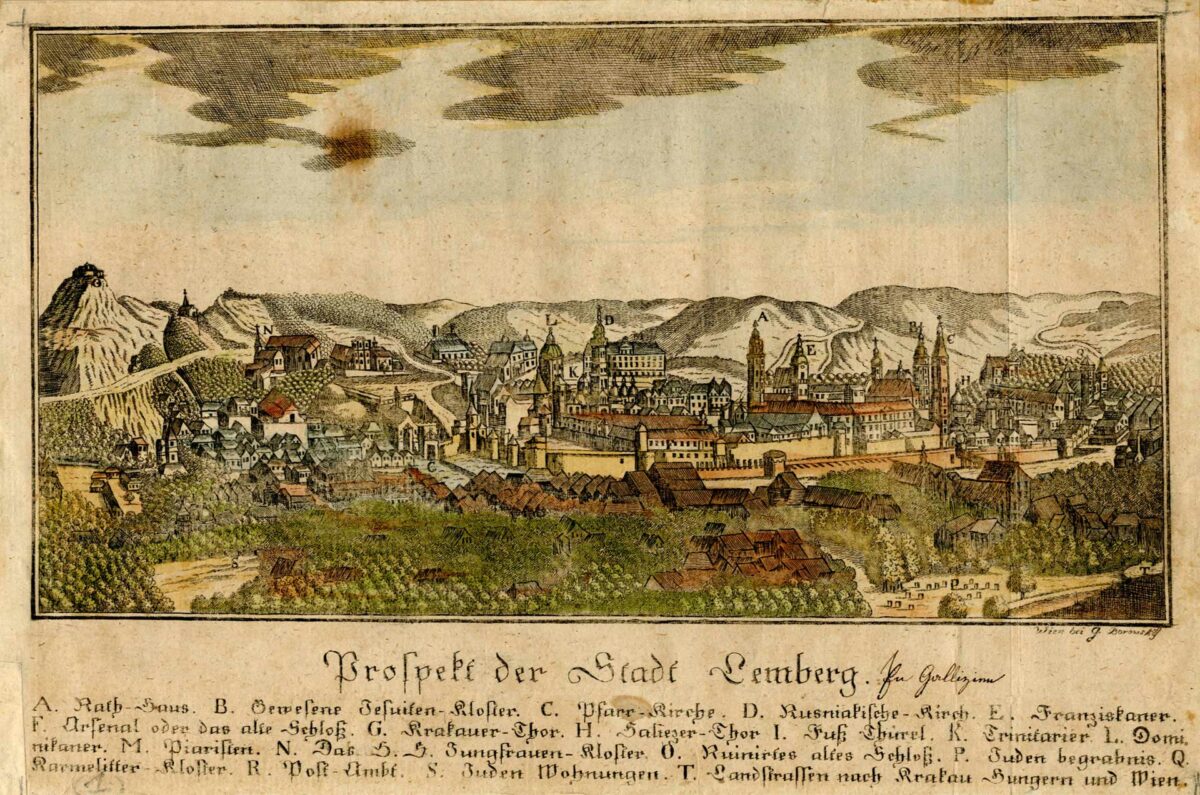

Two pogroms occurred in Lviv during this period, one in the suburbs and one in the center of the city, in which 129 Jews were killed, buildings and houses destroyed, and community property plundered. The perpetrators included Jesuit students and petty noblemen who had valuables in pawn with local Jews. A royal investigative commission and legal action by the Jewish community against the municipal authorities for failure to protect Jews resulted in a royal decree in 1668 in the Jews' favour. By invoking a thirteenth-century statute, the decree required that the city pay a tax for every Jew killed, that four officials be sentenced to one-year prison terms, and that the Jews affected be reimbursed for material losses. This decree was annulled in 1670 by the new Polish king in favour of the city officials. Still, provisions were made to reduce debts owed by the Jews to the city and remove discriminatory restrictions on trade and other economic activity.

sources

- Myron Kapral, "The Jews of Lviv and the City Council in the Early Modern Period," in Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry, Volume 26, Jews and Ukrainians, eds. Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Antony Polonsky (Oxford, 2014), 93–98.

1732–1762

A number of violent incidents involving Jews and Christians in the Ruthenian lands are recorded for this period. Some incidents were related to tensions created by the role of Jews as estate managers and tax collectors and the economic burden imposed on serfs by the authorities. The descent from financial conflict to violence, including violence by Jews against Christians, may also be explained by the confidence Jewish leaseholders felt under the protection of local lords and magnates and the humiliated position of the Orthodox Church after the Union of Brest. Threatening situations for Jews in Lviv and the Ruthenian province arose episodically, with more violent riots occurring in 1732, 1751, 1759, and 1762. These episodes provoked, in the Jews, feelings of mistrust and suspicion in the urban environment.

sources

- Myron Kapral, "The Jews of Lviv and the City Council in the Early Modern Period," and Judith Kalik, "Jews, Orthodox and Uniates in the Ruthenian lands," in Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry, Volume 26, Jews and Ukrainians, eds. Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Antony Polonsky (Oxford, 2014), 98–100 and 146;

- Judith Kalik, "Leaseholding," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1740s–1750s

Religious hostility towards Jews and Judaism, which had become prevalent in western parts of the Commonwealth, also found expression among the Polish Catholic population on Ukrainian lands in a number of blood libel trials. The pernicious blood libel — the false accusation that Jews murdered Christian children to use their blood for ritual purposes — had fueled anti-Jewish violence in western European countries (including England and France) since the twelfth century and had spread to Poland by the mid-sixteenth century. Blood libel trials took place in several towns. In Zaslav (Volhynia) in 1747, eight Jews were sentenced to horrible deaths by torture. Following a blood libel trial in Zhytomyr in 1753, thirteen Jews were baptized after forced confessions under torture. In 1756, one of the accused in a ritual murder trial in Yampil (in historical Podolia) escaped and was sent, through the coordinated effort of Jewish communities, to Rome to implore Pope Benedict XIV to protect Jews from ritual murder accusations in several other towns. Both Benedict XIV and the new Pope Clement XIII officially condemned the accusations. They also intervened with the Polish king on behalf of Jews, stating "there was no evidence that Jews need to add human blood to their unleavened bread called matzah." Even though the Papal edict and supporting documents were published in the Polish and European press, the accusations continued.

sources and related

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford and Portland, OR, 2010), vol. I, 27–28;

- Teller, "The Jewish Town, 1648–1772," Polin: 1000 Year History of Polish Jews (Warsaw, 2014), 151;

- Hanna Węgrzynek, "Blood Libel Accusations in Old Poland" (mid-16th – mid-17th centuries)," Proceedings of the World Congress of Jewish Studies, 1997.

Related

Chapter 4.4 1669

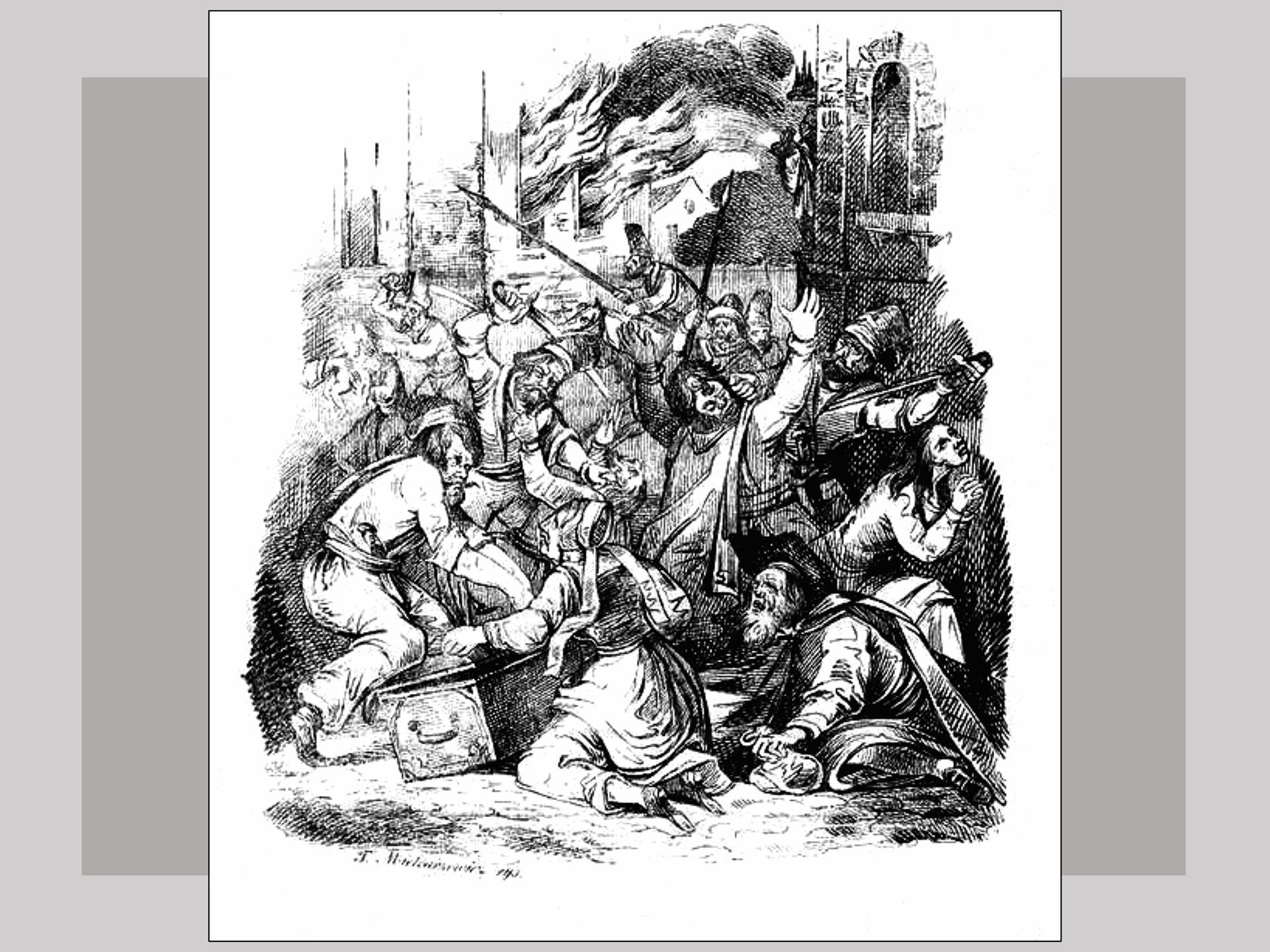

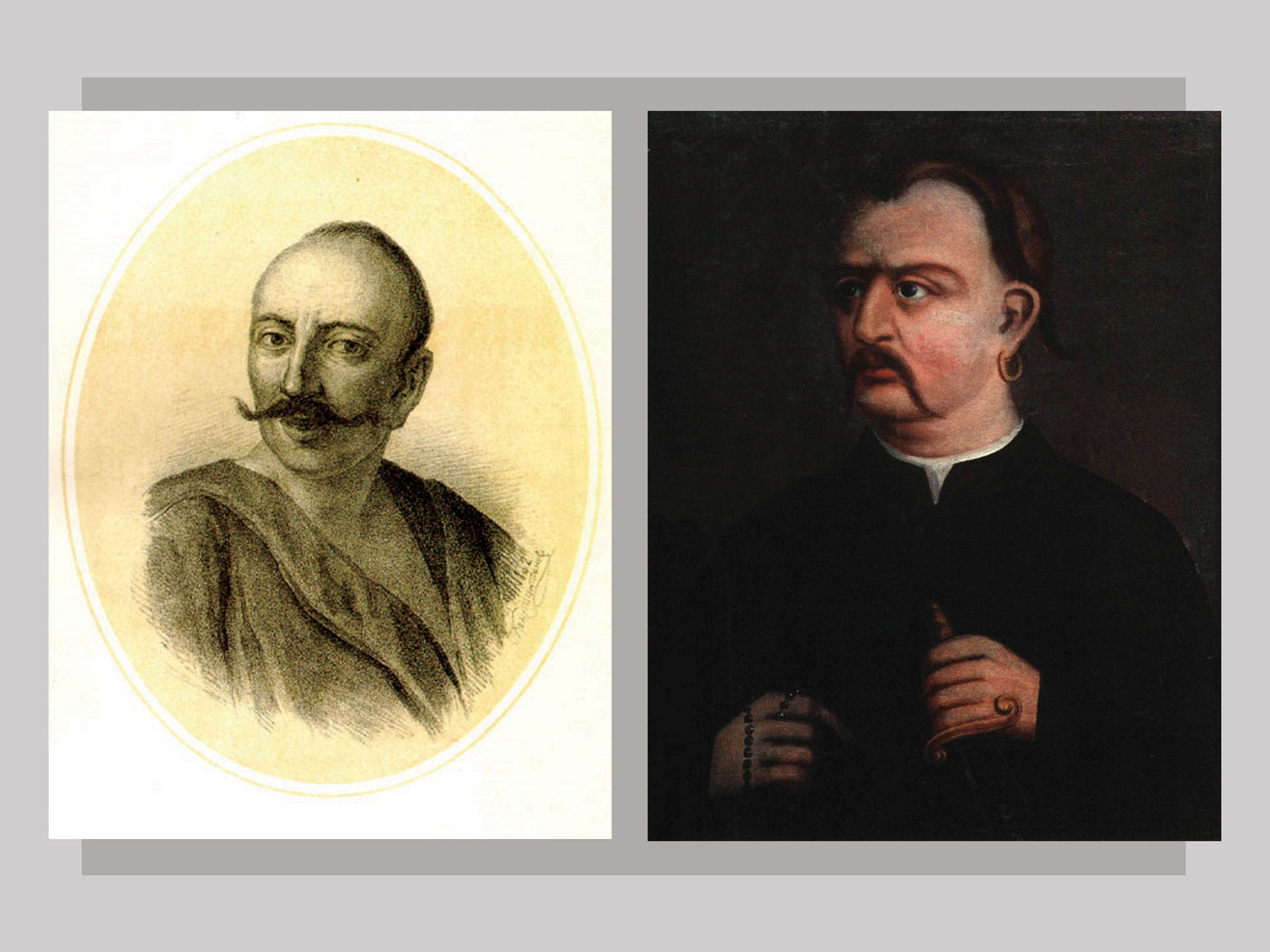

1768

Between 2,000 and 5,000 Poles and Jews were massacred in Uman over three days during a major revolt (known as the Koliivshchyna rebellion). The rebels, called haidamaky, consisted mainly of Zaporozhian Cossacks and Orthodox peasants. Their targets were Polish landlords, Roman Catholic and Uniate clergy, and Jews — all perceived as enemies to be overthrown. In Uman, the haidamaky were reinforced by Cossack forces led by Maksym Zalizniak and Ivan Gonta, the local Cossack commander of the Polish garrison. Gonta, who had been entrusted with defending the town, instead joined the attackers. In a further betrayal, the Polish governor negotiated a separate peace with the attackers, leaving the Jews to fend for themselves. Several thousand fled to the synagogue, where they were killed by cannon fire.

sources and related

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford and Portland, OR, 2010), vol. I, 29; Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 311–317;

- ChaeRan Freeze, "Uman," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

Related

Chapter 4.1 1768