1580s–1630s

Town documents and Jewish responsa literature offer examples of cooperative and neighbourly relations between Jews and ethnic Ukrainians during this period. For example, the Jews of Pereiaslav were included in the framework of the town's autonomous organization in 1620, and a rabbinic responsum (response to an inquiry relating to rabbinic law) reflects a practice of Ukrainian Jews to lend fine clothes and jewelry to Orthodox Ukrainians to wear in church during their holidays.

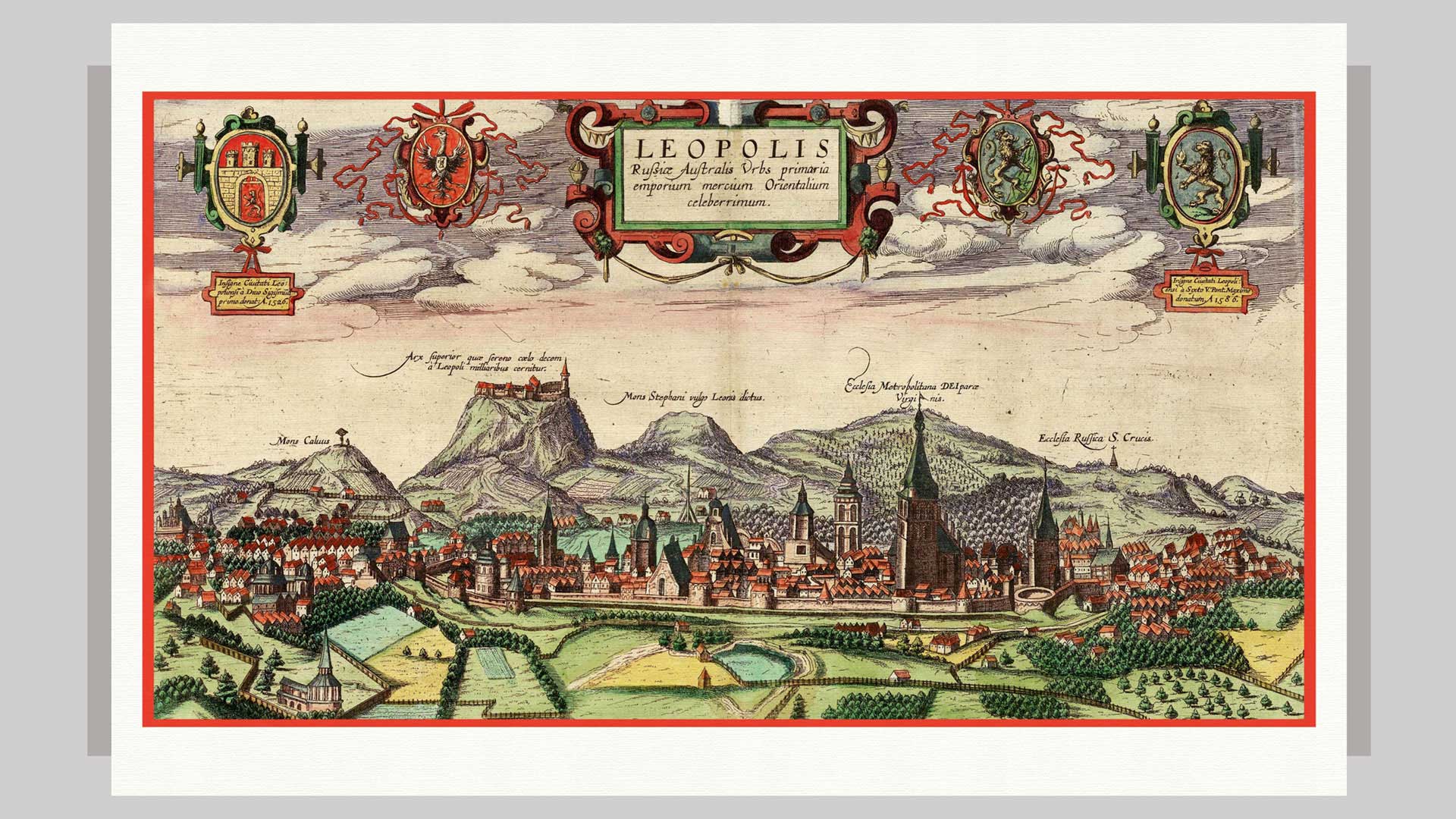

Though most Jews lived in the Jewish quarters officially designated for them in the city and the suburbs, they had daily contact with the urban population in the Lviv marketplace and other urban spaces. Within the city walls, the Jewish and Ukrainian quarters were located next to each other. They were familiar with each other's customs and religious ceremonies. Churches and synagogues in Lviv were adjacent to each other, both in the inner town and in the suburbs.

Read more...

Most instances of normal co-existence and everyday interchange between Jews and Ukrainians would not have been recorded and therefore escaped the attention of historians. However, documents relating to the economic sphere, for the city of Lviv for example, reveal a range of mutually beneficial relationships. Like other ethnic groups in Lviv (Armenians, Germans, Poles), Jews and Ukrainians used the services of lenders and credit unions, including services provided by religious institutions. There are documented instances of Ukrainians authorizing Jews to pay Ukrainians' debts; Jewish medics treating Ukrainians, who in return helped build houses for Jews; Jews from small Galician towns borrowing money from Ukrainian merchants; and Ukrainians from small towns entering into credit relationships with Jewish bankers in Lviv.

Looking at Ukrainian-Jewish relations during the early modern period from a gender perspective, historian Martha Bohachevsky-Chomiak observed that Jews were the "foreigners" Ukrainian women would be most likely to meet, especially in western Ukraine. Residing primarily in rural areas, Ukrainian women would encounter Jews in the nearby small towns on market days, either when selling their produce in the central square or visiting the surrounding Jewish-owned shops. They also frequently came into individual contact with Jewish women as neighbours in both urban and rural settings. Though their lifestyles varied considerably, Jewish and Ukrainian women shared a vital feature, which Bohachevsky-Chomiak identifies as "pragmatic feminism." That feature was manifest in their role as primary handlers of the family budget and their involvement in the grassroots life of their respective communities — a potential basis for common interests and cooperation.

sources

- Shmuel Ettinger, "Jewish Participation in the Settlement of Ukraine in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries," in Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective, Peter Potichnyj & Howard Aster, eds. (Edmonton, 1988), 29;

- Myron Kapral, paper presented at the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter Shared Historical Narrative Roundtable in Salzburg, Austria (June 2009);

- Martha Bohachevsky-Chomiak, "Jewish and Ukrainian Women: A Double Minority," in Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective, Peter Potichnyj & Howard Aster, eds. (Edmonton, 1988), 356–357;

- "Lviv in the 18th century: a unique historical reconstruction," Львів у ХVIII столітті: унікальна історична реконструкція.

1610

Among the Jews who accompanied the Cossack units in their campaign against the Muscovites were provisioners, merchants, and members of fighting units. An example of the latter, mentioned in a Hebrew source, concerns one of eleven Jewish fighters who served with three horses and was killed in action.

sources

- Shmuel Ettinger, "Jewish Participation in the Settlement of Ukraine in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries," in Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective, Peter Potichnyj & Howard Aster, eds. (Edmonton, 1988), 26.

1650s–1700s

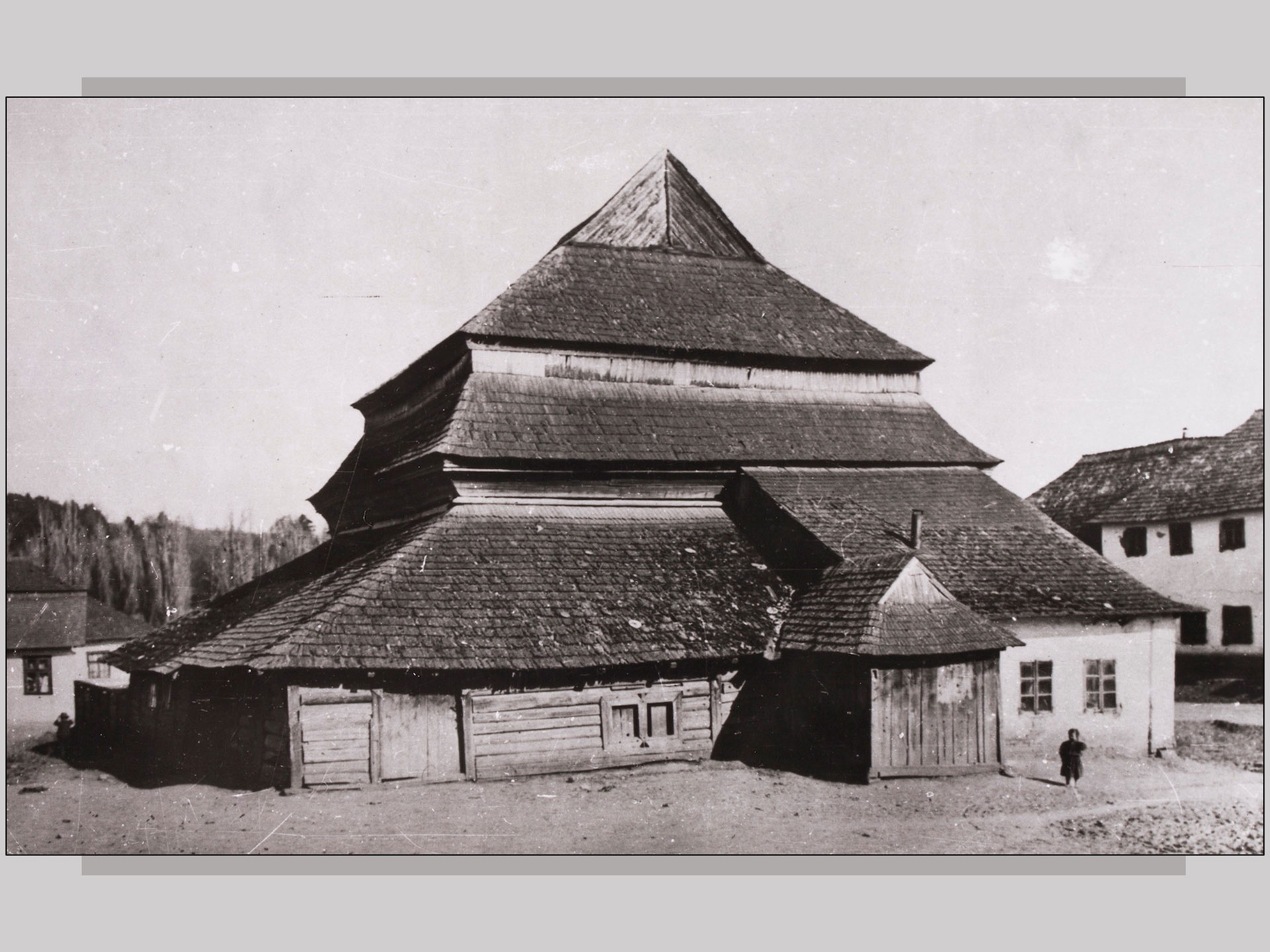

Though the religious sphere was generally one separating Ukrainians and Jews during this period, it also involved cooperation, shared influences, and economic interaction. Wooden synagogues were often built by the same Jewish and non-Jewish craftsmen who built wooden churches, giving both a distinctly regional character. While the interior wall paintings reflected a complex ensemble of artistic influences, they also featured Polish and Ukrainian stylistic elements and folk-art motifs.

Read more...

Relations between the three churches (Orthodox, Uniate, and Catholic) on Ukrainian lands and Jews were primarily economic. Contacts often related to the accumulated debts that Jewish communities and councils owed to the three churches, mostly to the Catholic Church. Other contacts related to the expansion of Jewish leaseholds on church property, involving tithes and liturgy taxes, and, most prevalently, in the liquor trade. Another element of economic interaction was the practice of the churches to lease or sell housing and land plots to Jews in zones under their jurisdiction (the ecclesiastical jurydyki that were independent of municipal laws) despite official prohibitions.

sources

- Thomas C. Hubka, "Ukrainian and Jewish Influences in the Art and Architecture of Pre-Modern Wooden Synagogues, 1600–1800" in Cultural Dimensions, 54–67;

- Judith Kalik, "Jews, Orthodox and Uniates in the Ruthenian lands," in Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry, Volume 26, Jews and Ukrainians, eds. Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Antony Polonsky (Oxford, 2014), 132.

1700s

As Jews were barred from lands controlled by the Cossacks unless they converted to Christian Orthodoxy, a few did convert, and some became Cossacks. Several Cossacks of Jewish birth or their descendants rose to leading positions in the Cossack government and military — as was the case for families named Markovych/Markevych, Hertsyk, and Kryzhanivskyi.

Before the partitions of Poland, the Russian state did not allow Jews to settle on its territory. The Cossacks of the Hetmanate had petitioned the Russian state several times to allow Jews to enter their territory, since they had often relied on the services of Jewish merchants. However, the Russian rulers would not agree.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 267.

- John-Paul Himka, Ten Turning Points: A Brief History of Ukraine.