1807

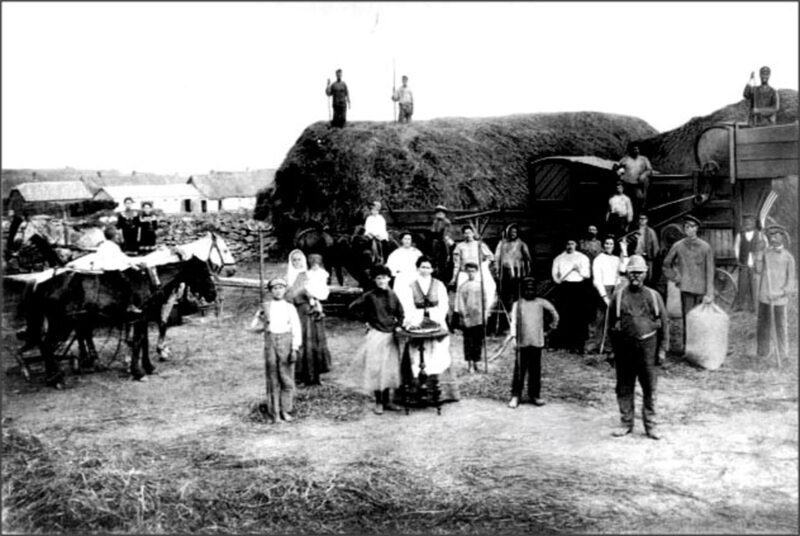

The Russian government ordered the expulsion of Jews from villages in its aim to divert Jews from the rural economy and the liquor trade. The bulk of the expelled Jews were then settled on agricultural land in New Russia. Four colonies of Jewish farmers were established in the province of Kherson, numbering three hundred families, consisting of two thousand people. The project proved to be a success. By 1897 there were 23,000 Jewish families (with 43,531 male residents and around 100,000 people in total) engaged in farming in New Russia. Southern Ukraine was to become the most significant Jewish farming community in the world prior to the rise of the kibbutz movement in Palestine in the 1920s.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) I, 349;

- Aleksei Miller, “Imperiia Romanovykh i evrei,” in Imperiia Romanovykh i natsionalizm (Moscow, 2006), 109-110.

1819–1830s

Odesa

The rapidly growing city of Odesa became a free port, attracting new business and new settlers. Jews from Galicia adapted well to the intensely competitive environment of the burgeoning port city, especially in banking and the grain trade. According to the Jewish merchant and author Joachim Tarnopol (1810–1900): "The Galicians are generally employed as bankers, merchants, or brokers...Their connections with St. Petersburg, Brody, and Berdychiv, their extensive relations with some financial notables of Europe, as well as their care in punctually fulfilling their obligations have placed them in a position to undertake all of Odesa's banking operations." By the 1830s, Jews had come to dominate the role of intermediaries in Odesa's grain trade.

sources

- Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe (New York, 2015), 361;

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) II, 176.

1820s–1850s

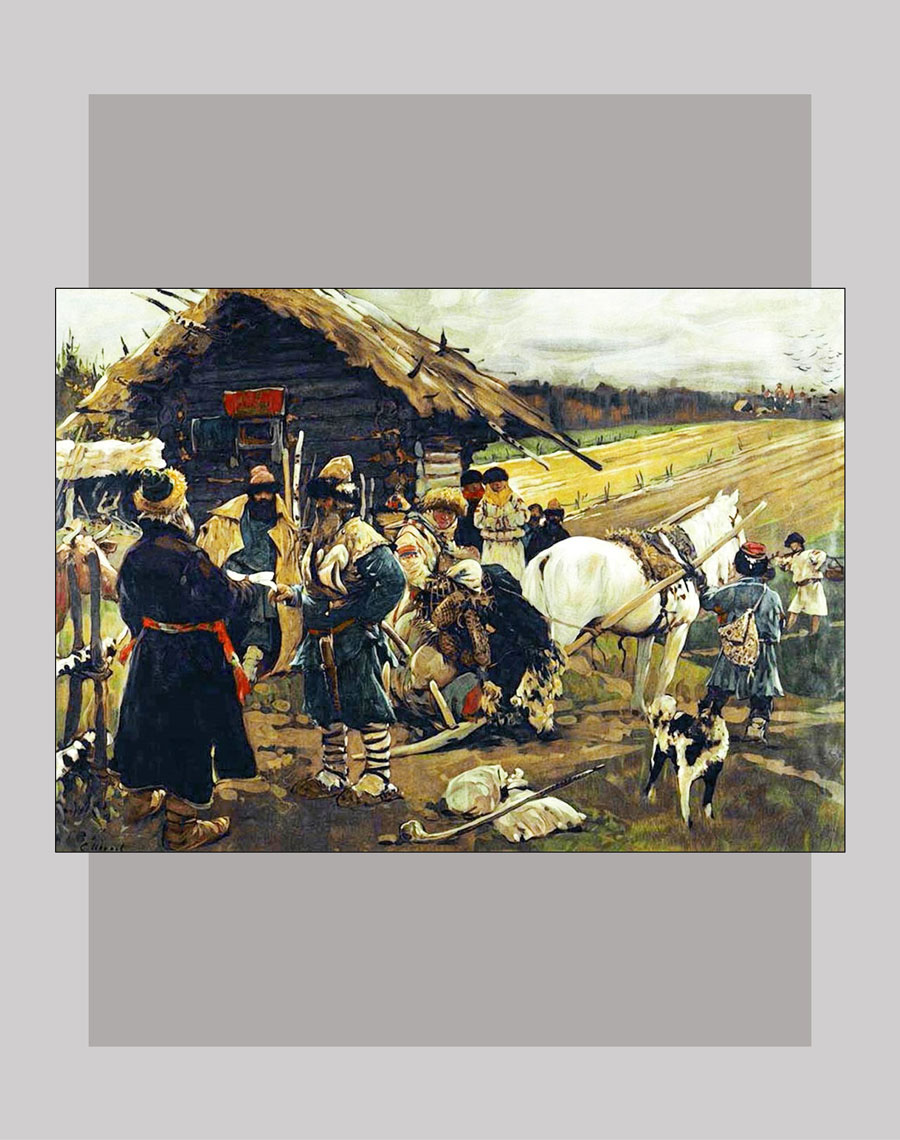

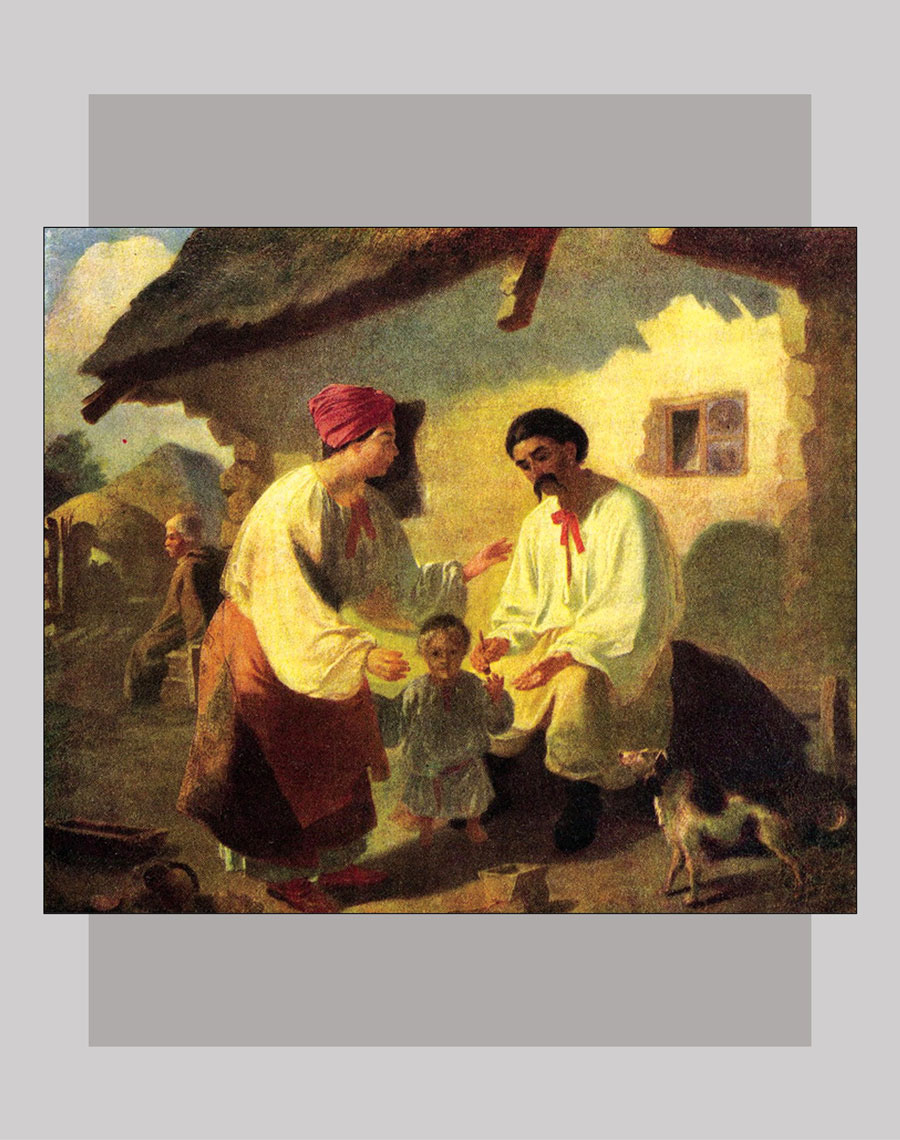

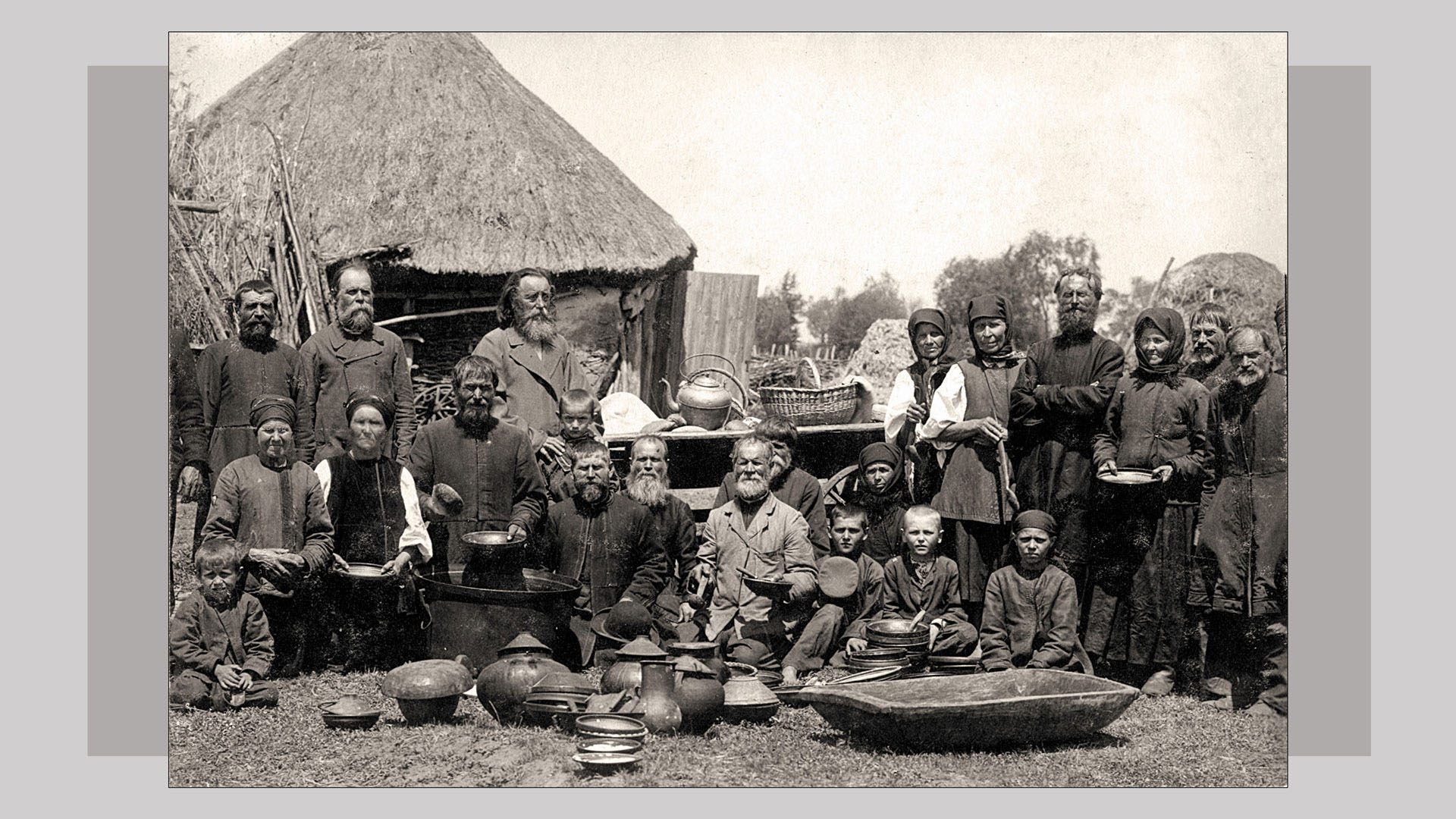

State peasants and serfs

The peasantry was the largest socioeconomic stratum in Dnieper Ukraine during this period. Until the reforms of the 1860s, the peasantry consisted of two distinct and legally differentiated groups — state peasants and serfs. State peasants were obliged to pay various taxes and perform duties for the state, such as building and maintaining roads. In contrast, serfs on state-owned lands leased to local gentry were obligated to perform tasks for their landlords. By 1837, state peasants could buy land from the state with full property rights and their work duties to the gentry were abolished. However, serfs owned by landlords (whether nobles, Cossacks, or the church) continued to be tasked with obligatory duties for their landlords.

Read more...

Serfs in tsarist Russia enjoyed freedom of movement until 1783, when Empress Catherine II issued a decree in response to demands from the local Russian nobility and the Cossack gentry. The decree gave the latter control over their peasants in exchange for their taking responsibility for payment of a new poll tax. The vast majority of serfs fulfilled their obligations in the form of onerous labour dues, which could be anywhere from three to six days per week. By the 1840s, the landlords assigned many serfs (around 25 percent in Left-Bank Ukraine) to work in plants and factories, creating another stratum — landless serfs.

sources

1820s–1860s

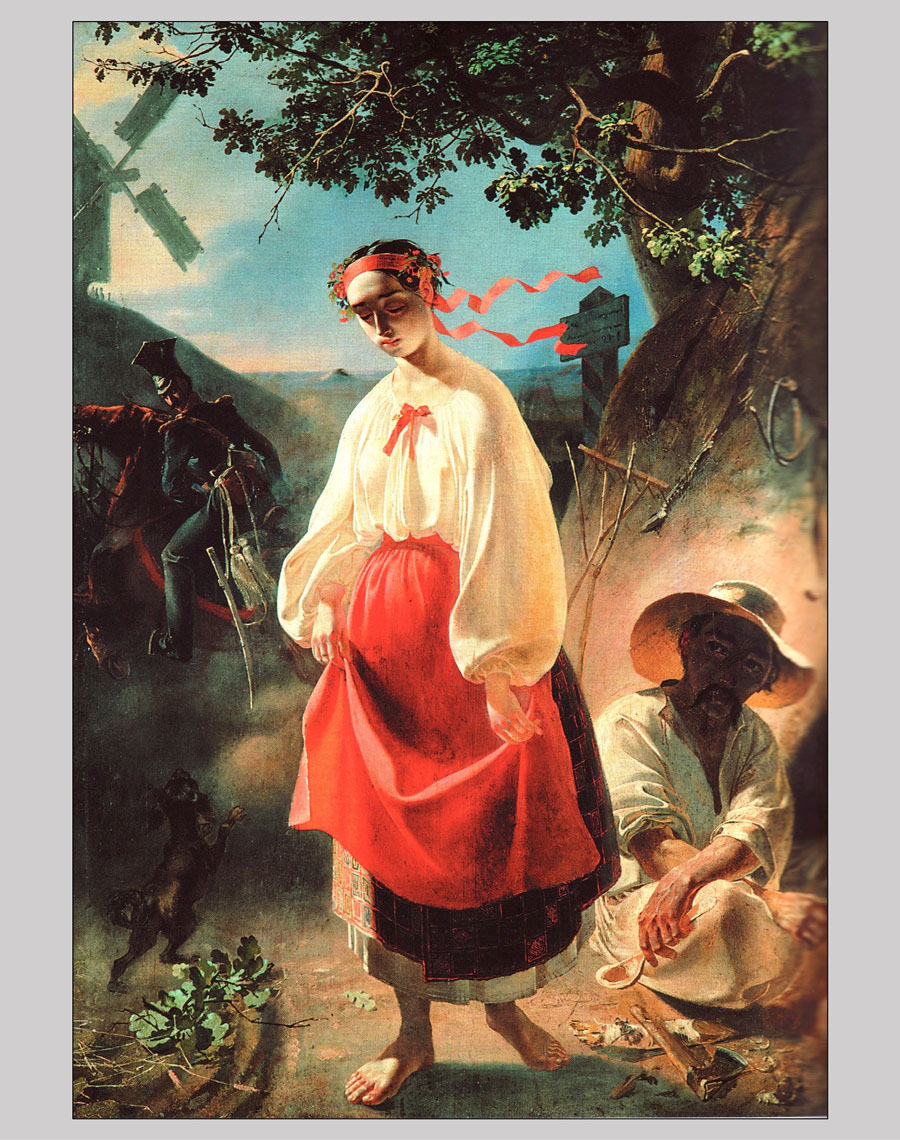

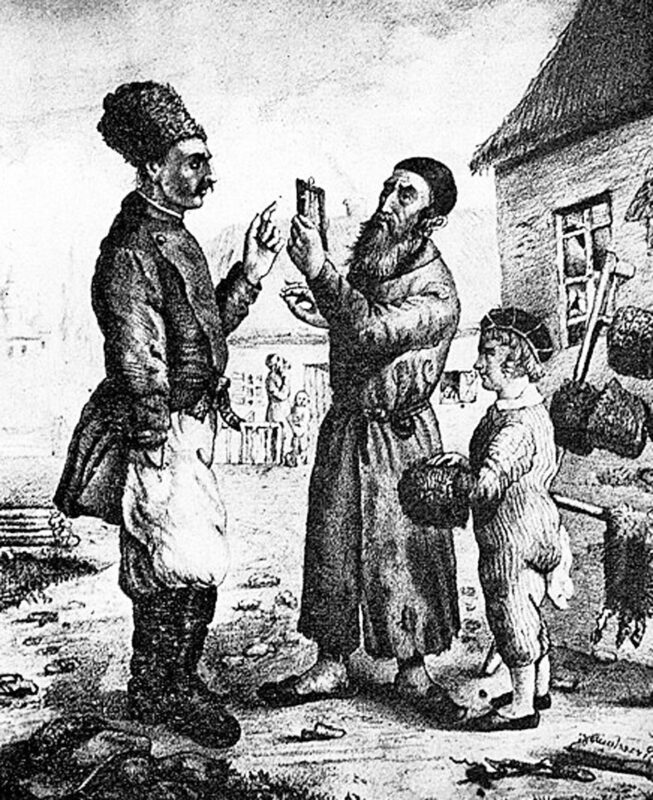

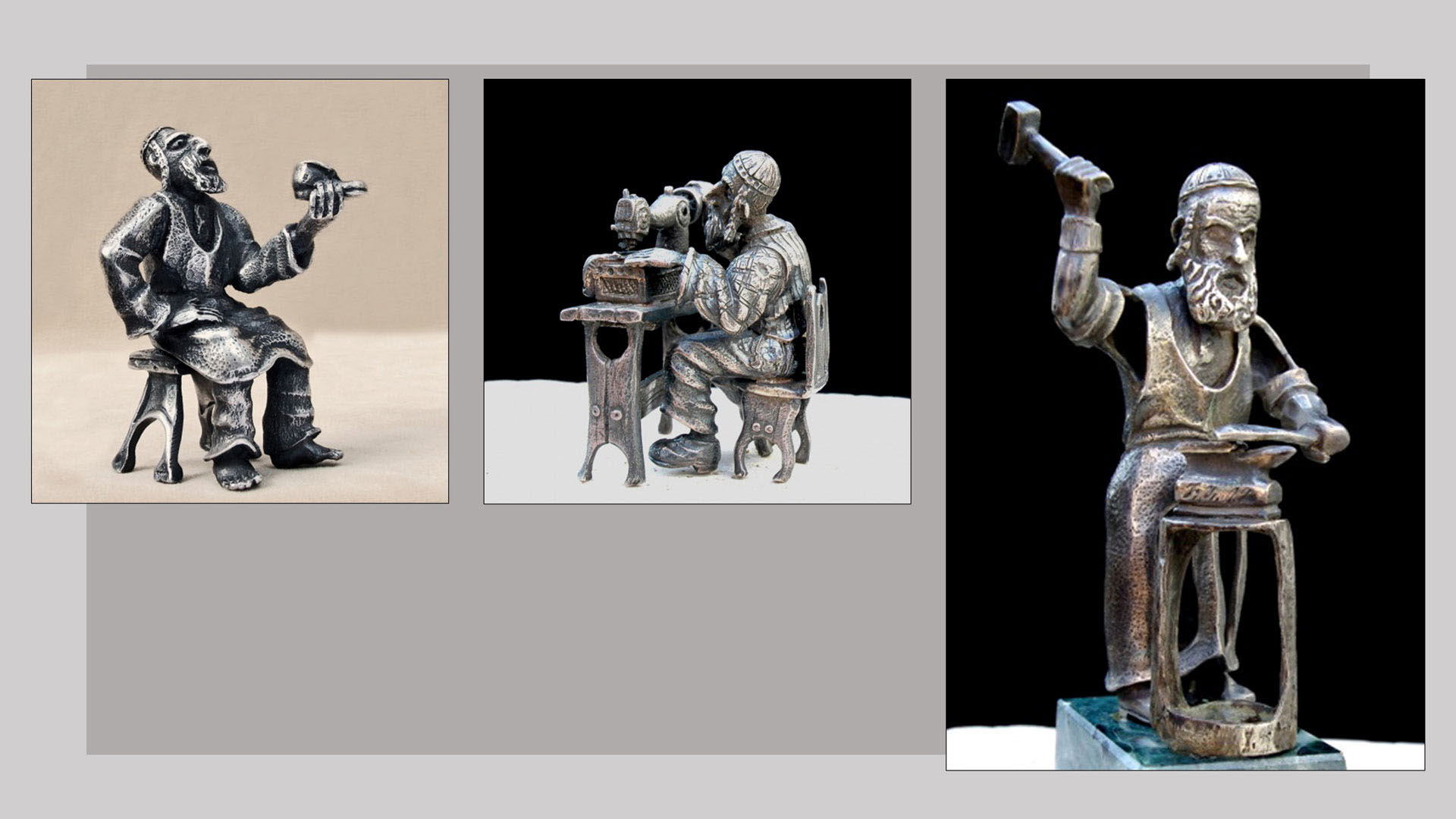

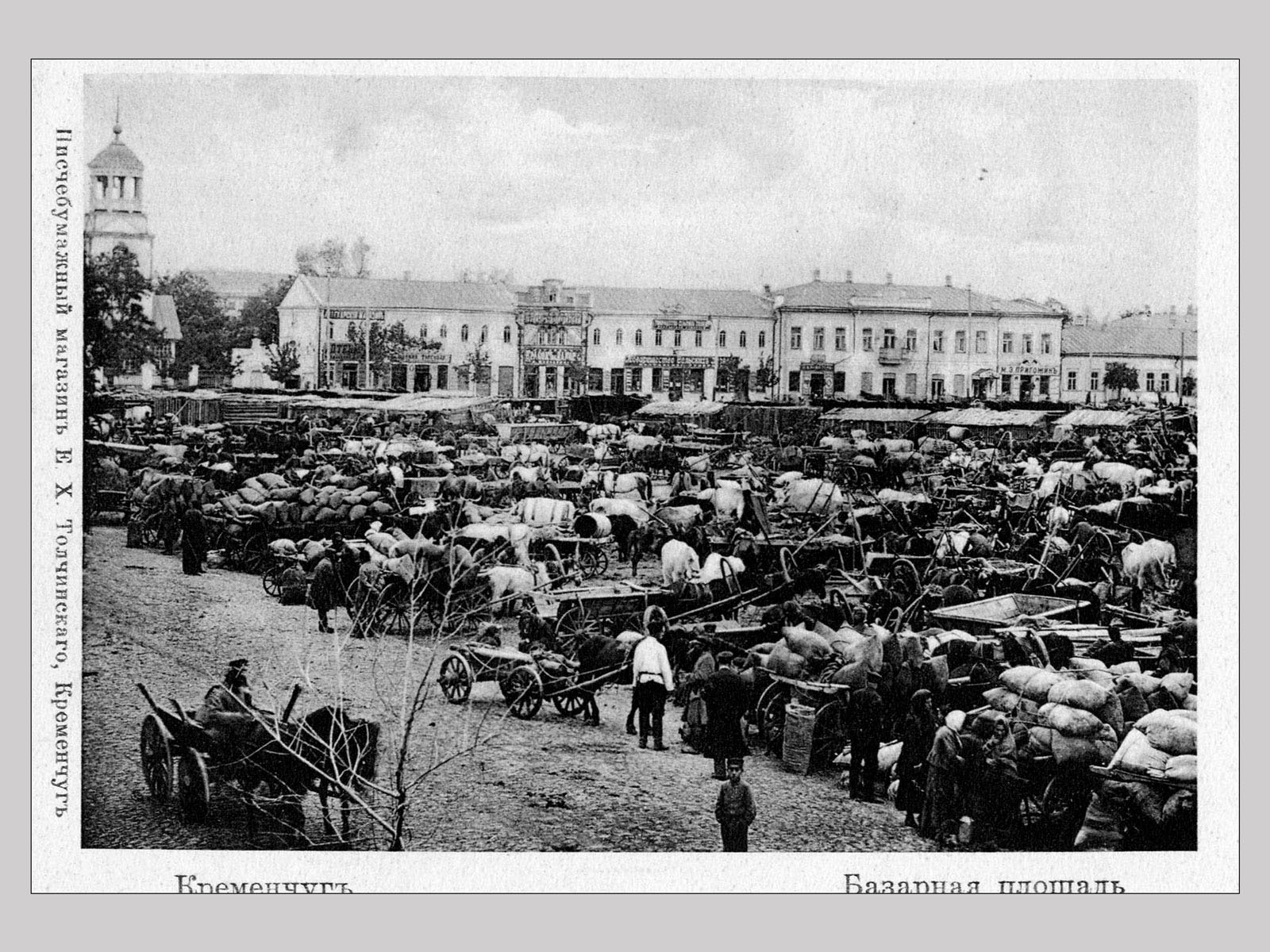

Marketplaces as sites of Ukrainian-Jewish interaction

Administrative attempts by Russian authorities, beginning in the early 1800s, to forbid the leasing of estates to Jews and expel Jews from rural areas were gradually implemented during this period. In the 1840s, however, Jews could still lease taverns and inns even in places where Jewish settlement was restricted, such as Kyiv and Kharkiv. In the shtetls (small towns in the Pale of Settlement with significant Jewish populations) surrounded by large Ukrainian rural populations, the local marketplace became a key site of Ukrainian-Jewish interaction.

Read more...

The number of industrial enterprises in Dnieper Ukraine grew from 200 in 1793 to 779 in 1832 to 2,329 in 1860. Factories producing distilled alcohol, soap, metallic and leather wares, glass, paper, and especially textiles flourished, as did enterprises that processed sugar and tobacco. Of factory proprietors in 1832, 47 percent were Russian, 29 percent were Ukrainian, and 17 percent were Jewish.

Being a predominantly urban population, Jews engaged primarily in operating small shops and businesses and in trade, banking, and industry. In Right-Bank Ukraine, Jews were generally dominant among guild merchants. According to the 1897 census, in nine “Ukrainian” provinces, 56 percent of the 67,709 officially registered merchants (a number that includes their families) were Jewish, followed by Russians (30 percent) and Ukrainians (7 percent). Jews comprised the majority of merchants in all these provinces except for Kharkiv, where Russians and Ukrainians were more numerous: 3,965 Russians (64.2 percent), 1,126 Ukrainians (18.2 percent), 748 Jews (12 percent).

sources

- Judith Kalik, "Leaseholding," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010);

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 347, 358;

- M. Donik, "Chysel’nist’ ta etnichno-konfesiinyi sklad kupetstva Ukraїny v XIX – na pochatku XX st.," Ukraїns’kyi istorychnyi zhurnal, 5 (2009), 74–76.

1820s–1860s

Karaites and Krymchaks

The imperial authorities made a legal distinction between the Karaites and the Rabbinite Jews and accorded the Karaites special privileges, including exemption from the double tax (imposed on the Jewish population) and release from obligatory military service (1827). As a result, some Karaites were able to accumulate wealth. In 1863 the Karaites were granted equal rights with Christian subjects of the tsar. The Krymchaks also enjoyed a benevolent attitude on the part of the Russian authorities. The tiny community of artisans was neither under suspicion of disloyalty, as were the Crimean Tatars, nor perceived as commercial competitors, as were the Crimean Greek and Armenian communities.

1850s

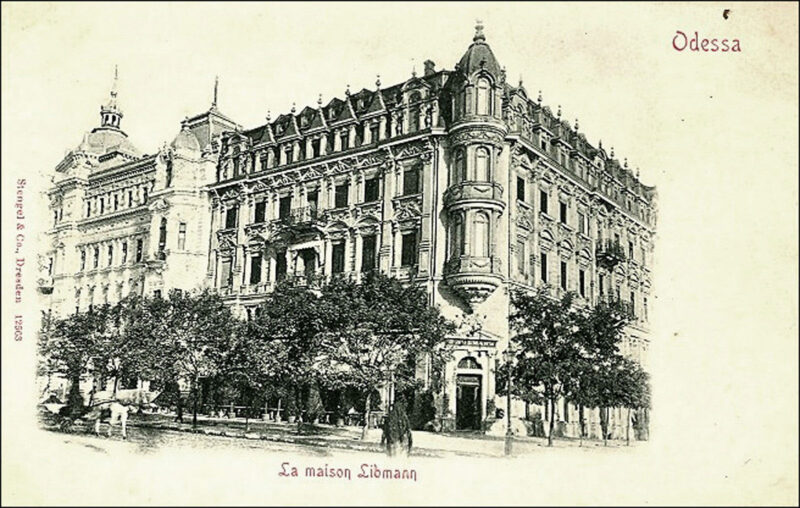

The first Jewish banker in the Russian Empire, Israel Halpern, established himself in Berdychiv, an important market town in Podolia. Other banking and trading firms, such as Ephrussi, Gurovich, and Trakhtenberg, moved to Odesa when the town of Berdychiv declined in importance in the 1860s.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) II, 184.

1851

The number of Jewish farmers grew from 3,600 in 1830 to 15,500 in 1851, almost half of whom resided in the province of Kherson.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) I, 386.

1850s–1890s

The Russian government's economic policies led to the impoverishment of most Jewish merchants and the emergence of a small group of prosperous traders. Policies responsible for this result include the replacement of seasonal fairs with permanent markets and the creation of administrative barriers to traditional trading links. According to a contemporary description of a fair in Ukraine: "around each Jewish wholesale merchant a hundred petty, poor Jews crowd, who secure goods from the wholesale store to sell... lending commerce a certain feverish vitality." According to the Jewish Colonization Society, in 1898, the poor comprised 17 percent of the Jewish population in Volhynia and Chernihiv provinces and 20 percent in the Katerynoslav, Kyiv, Podolia, Poltava, and Kherson provinces.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) I, 388.

1850–1851

The abolition of Jewish autonomous administration in 1844 profoundly impacted the integrity of Jewish communities in the Pale of Settlement, with some groups petitioning secession from the community. The Jewish artisans of Dubno, Bila Tserkva, and Volodymyr-Volynsky made such requests. As stated by members of the Jewish artisans' guild in Bila Tserkva, they wished "to throw off the yoke of the Jewish community which, according to its ancient traditions, looks with contempt upon artisans and takes too large a share of taxes and army recruits from them." Jewish merchants in Kremenchuk made a similar petition for secession.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) I, 373.

1858

Prince Illarion Vasilchikov, governor-general of Kyiv, Podolia, and Volhynia, advocated for Jewish master craftsmen in his region to be allowed to move to the interior of Russia. These views, submitted in a report to the Imperial Minister of Internal Affairs, were rejected in favour of more gradual and limited measures.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) I, 396.

1860s

Russian landlords continued to employ Jews as leaseholders in Ukrainian lands. According to an 1868 estimate, Jews leased 701 out of 5,143 noble estates in Kyiv, Volhynia, and Podolia.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) I, 423.

1860s–1870s

Alexander II's economic reforms had opened opportunities for a few select groups of Jews. Around 100 Jewish merchants of the First Guild were entitled to live and trade in the interior provinces on equal terms with Russian merchants, on condition that they continued to be paying members of the First Guild for at least ten years. University graduates were permitted to settle anywhere in the empire and to enter the civil service. By 1879, residence restrictions were also lifted for professionals with technical diplomas, including pharmacists, dentists, physicians' assistants, and midwives. While a few Jews prospered conspicuously during this period, the vast majority barely eked out a living.

Read more...

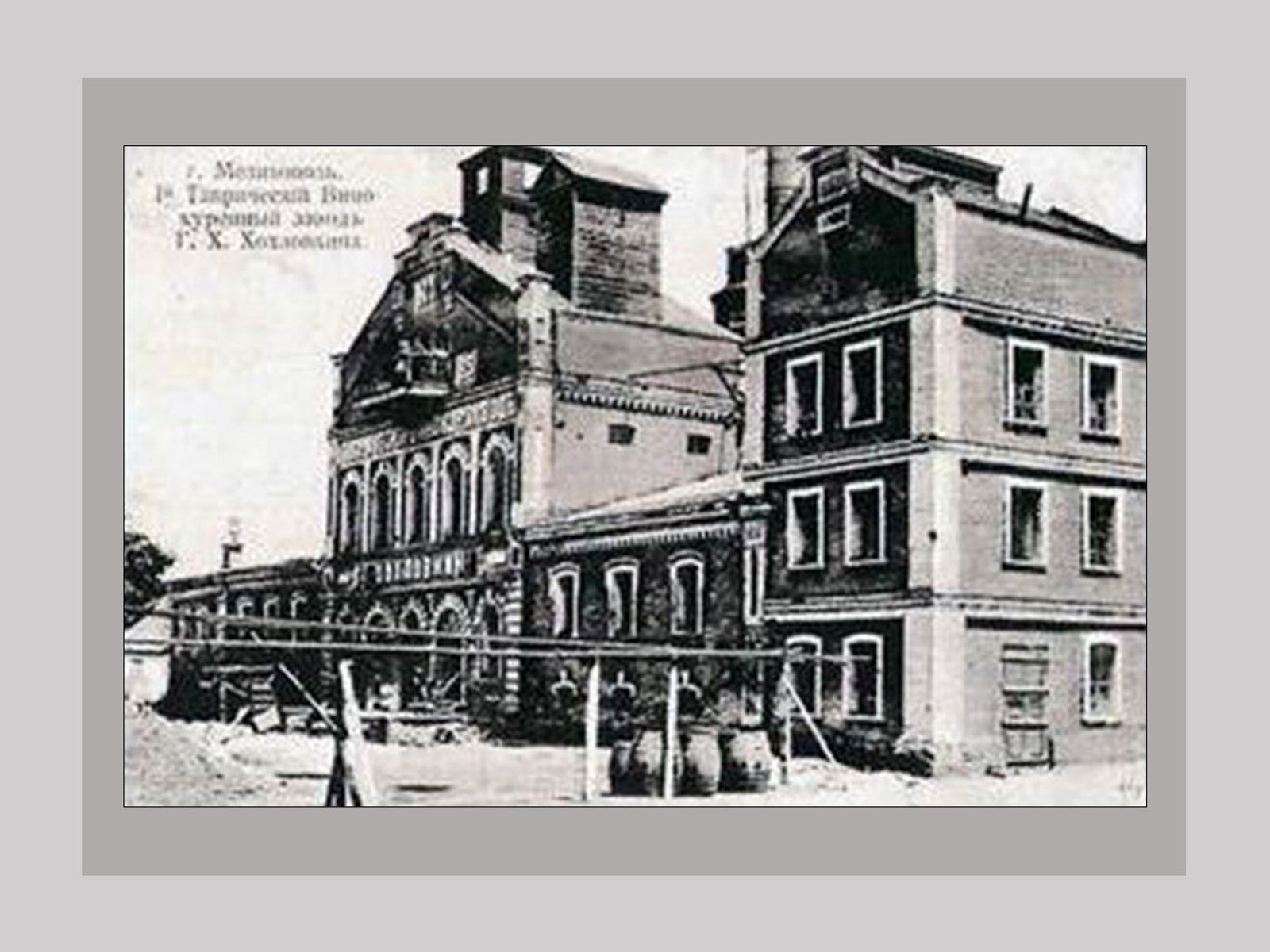

During this period, individual Jews became prominent in banking and trade and in certain industries, such as distilleries, sawmills, tobacco processing, railway building, urban construction, manufacture of bricks and candles, and textile production. By the 1890s, one-quarter of all sugar refined in the Russian Empire was carried out in factories owned by the Kyiv industrialist and Jewish philanthropist Israel Brodsky and his sons Lazar and Lev. Non-Jewish sugar industrialists, such as the Ukrainian Tereshchenkos and the Russian Bobrinskiis, often operated on a much larger scale than their Jewish counterparts but were not as heavily involved in the marketing side of the business. For example, the Brodskys and a few other Jewish sugar barons played a key role in Kyiv's annual Contract Fair and after 1873 at the Kyiv Exchange. Other Kyiv Jewish entrepreneurs, such as David Margolin, made fortunes in the shipping and milling industries.

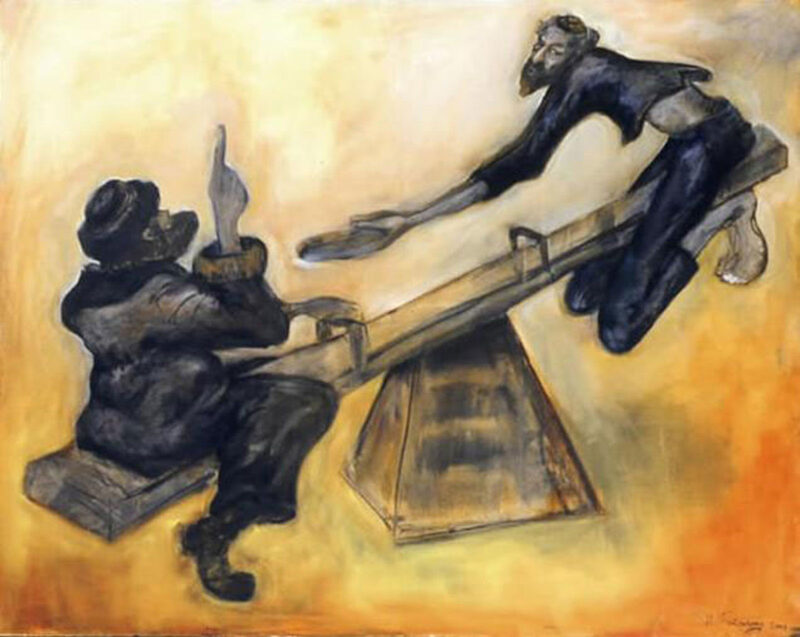

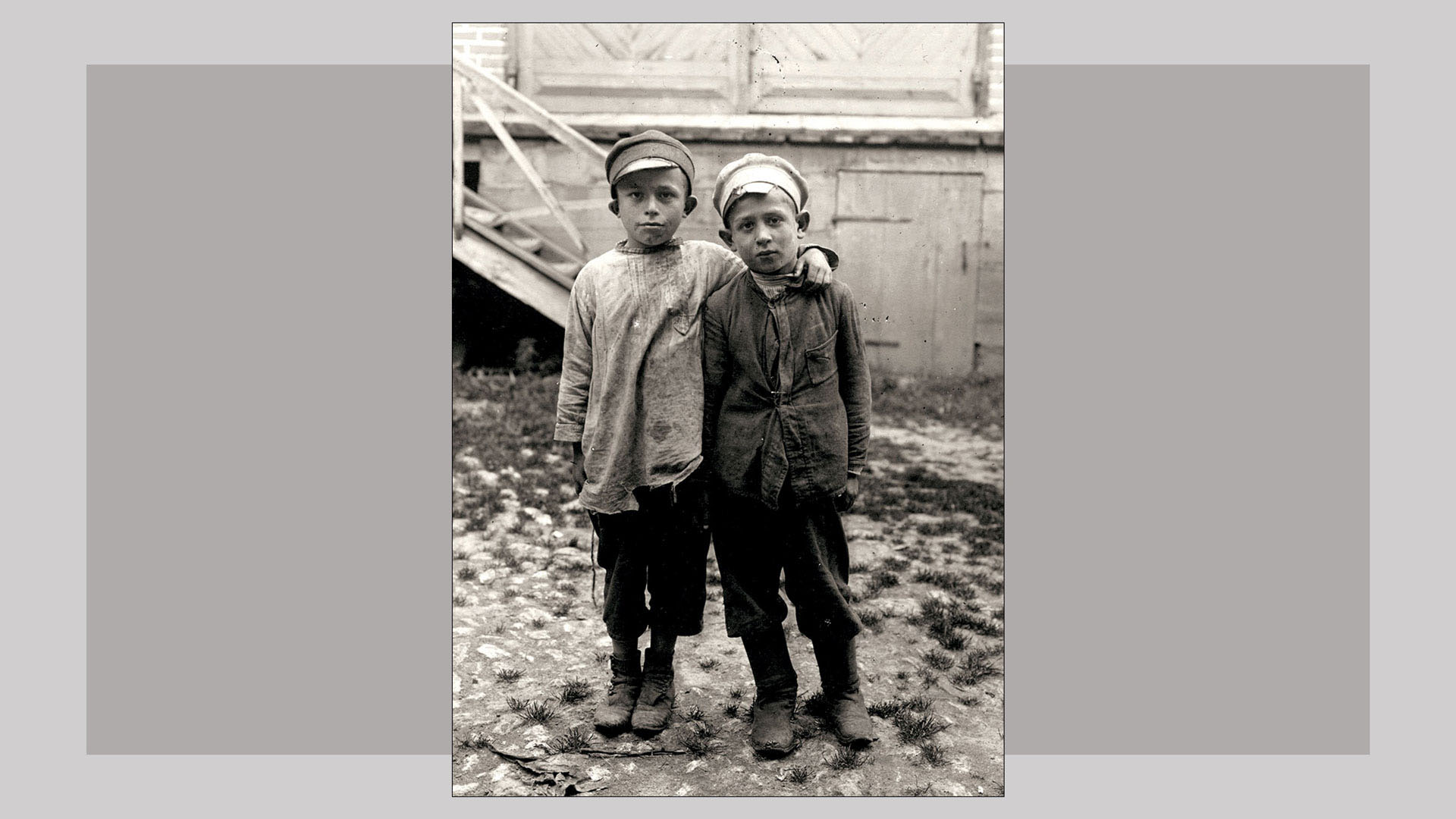

While the wealthiest Jews attracted the most attention, the vast majority of Jews struggled to make a living in various small-scale ventures, petty trade, and crafts. A negative effect of the achievements and high profile of individual Jews in the region's economy was that Jews as a whole came to be seen as profiteers and responsible for the ills of industrialization, even though the vast majority of Jews lived a modest existence, often bordering on poverty.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) I, 398;

- Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern and Antony Polonsky, Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry, Volume 26, Jews and Ukrainians, (Oxford, 2014), 16;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 360;

- Natan M. Meir, Kiev, Jewish Metropolis: A History, 1859–1914 (Indiana University Press, 2010), 39–40.

1870–1900s

Welsh entrepreneur John James Hughes came to southern Ukraine in 1870 to establish metal works, initiating the development of the Donets industrial basin and inaugurating Russian labour migration to Ukraine. The rise of the coal industry along the Donets river, where most of the coal reserves were found, led to a population boom in the region, largely driven by Russian settlers.

Read more...

About 80 percent of the labour force consisted of migrant workers, often from Russia. According to the 1897 census, 79 percent of the workers at the steel mills in the Donbas-Dnieper Bend were not Ukrainians. Local Ukrainian peasants preferred to seek work on farms or at more traditional industrial enterprises like distilleries. The industrial development of the region expanded with the construction of railroads linking it with central Russia and the sea, and even more so with the building of the first Catherine Railroad (1884, now known as the Dnipro Railroad) and the second Catherine Railroad (1902), linking the Donbas to the Kryvyi Rih Iron-Ore Basin.

sources

- Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe (New York, 2015), 362;

- Volodymyr Kubijovyč, "Donets Basin," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1984);

- Charters Wynn, Workers, Strikes, and Pogroms: The Donbass-Dnepr Bend in Late Imperial Russia, 1870–1905 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992), 45–47.

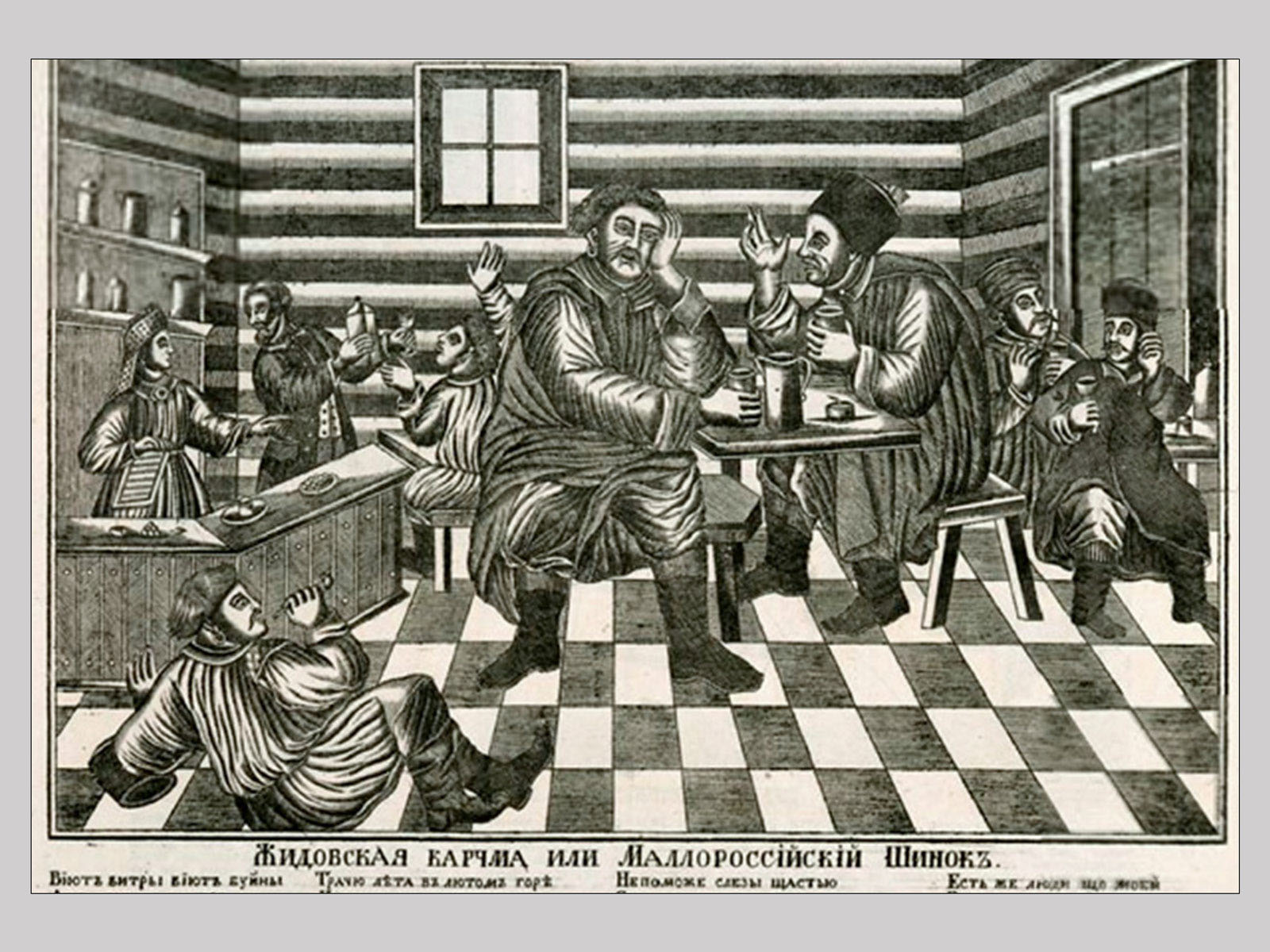

1881–1894

Blaming Jewish tavern keepers for peasants' excessive drinking and impoverishment, a common theme among reformers in nineteenth-century Galicia, had parallels in Russian-ruled Ukraine. The new minister of the interior, Count Nikolay P. Ignatyev, set up several provincial commissions, as well as his own Jewish Committee, chaired by his deputy D.V. Gotovtsev. The latter committee deliberated on proposed measures to restrict Jewish residence in rural areas and ban Jewish involvement in the liquor trade. These deliberations and the response of the Council of Ministers led to the 1882 May Laws (in effect until 1917), which barred Jews from buying or leasing rural land and conducting business on Orthodox holy days (among other restrictions). However, these laws did not ban Jewish involvement in the liquor trade — which became illegal for Jews only in 1894, when Alexander III approved the establishment of a state liquor monopoly in the Pale of Settlement.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) II, 7–12, 16.

1883–1887

The special High Commission for the Study of Existing Laws on the Jews (the Pahlen Commission) offered a more balanced assessment of the role of Jews in the economy than that provided by hostile government officials. It attributed Jewish overrepresentation in trade to government restrictions on other opportunities for Jews and the emergence of a better developed retail network in the Pale of Settlement than existed in the interior provinces. The Commission found that Jews dealt with items essential for the rural population and that their role at local fairs and markets was largely beneficial, contributing to competition and keeping prices low. At the same time, it noted that most Jewish traders were, in fact, increasingly impoverished.

Read more...

The Commission concluded that the abuses attributed to Jewish economic activity were not unique and would disappear as the Russian economy became more developed and Jews entered other fields of activity. The majority of the Commission's members endorsed the gradual removal of virtually all discriminatory legislation vis-à-vis Jews. However, Tsar Alexander III and his close advisors rejected their recommendations.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) II, 11–13;

- Hans Rogger, Jewish Policies and Right-Wing Politics in Imperial Russia, (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1996), 63.

1890s–1900s

The considerable urban and industrial growth in Dnieper Ukraine largely bypassed the large population of former Ukrainian serfs. Ethnic Ukrainians made up only 18 percent of the population in the rapidly growing eight largest cities, which dominated the urban economy and accounted for more than three-quarters of Dnieper Ukraine's industrial production and workforce.

Read more...

Scholars have offered an explanation for this phenomenon. Unlike Russian peasants who were encouraged to migrate to the cities, Ukrainian peasants continued to pay their dues to their landlords in labour rather than in monetary rents. Thus, as more Russians became skilled or semiskilled labourers, an estimated 93 percent (ca. 1900) of Ukrainian migrant labourers remained unskilled manual labourers, and therefore at a disadvantage in eastern Ukraine's developing industrial economy. At the same time, the peasants' access to land became more difficult, as many still had huge redemption payments following their emancipation from serfdom, while those employed in factories and mines received no land at all. As a result, more and more peasants became indebted, without land, and impoverished.

sources

1906–1914

Nearly a quarter of Kyiv's Jews in 1906 were so poor that they required charitable relief to be able to celebrate Passover. At the same time, the percentage of professionals in the city's Jewish community — lawyers, doctors, writers, and journalists — was very high (13 percent). This segment of the Jewish population is well represented by Arnold Margolin, a Ukrainian-Jewish political leader, scholar, and lawyer.

Read more...

Economic changes in the previous decades gradually displaced traditional localized marketplace economies, affecting the social stratification of Jews in the Russian Empire. The most consequential changes include the growing urbanization following the emancipation of the serfs, the introduction of the railroad, and small-scalegovernment-sponsored industrialization. The vast majority of Jews, whose livelihoods for centuries relied on providing goods and services to peasants at town markets, were now increasingly forced to seek alternate sources of income. Large numbers, including young women, began to work in small factories and workshops in towns and cities. While most Jews remained in the lower middle class and became increasingly impoverished, some succeeded in joining the prosperous middle class, and a few entered the ranks of the upper-middle class.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) II, 183;

- "Margolin, Arnold," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1993);

- Michael Stanislawski, "Russia: Russian Empire," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

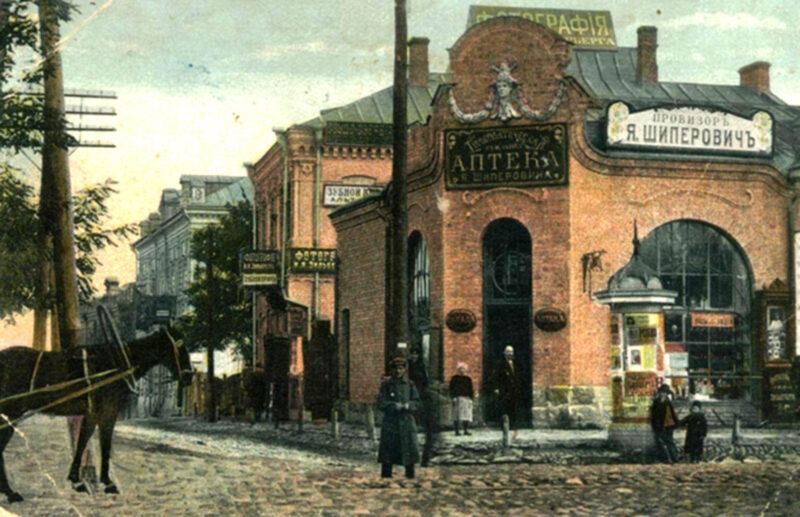

1910

Jews were prominent in Odesa's economy. Jewish firms controlled 90 percent of the export trade in grain. Jews owned more than half of the city's large stores and trading firms and were predominant in the manufacture of a range of products. Thirteen of the eighteen Odesa banks had Jewish board members and directors. At the same time, there was considerable Jewish poverty in Odesa, as destitute Jews from the Pale sought opportunities (often illusory) in the rapidly growing city.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010) II, 177.

1912–1914

Photographs taken by Solomon Yudovin during the ethnographic expeditions led by S. An-sky in the Pale of Settlement indicate the prevalence of poverty among the Jews of Podolia and Volhynia.