1300s–1490s

Grand Duchy of Lithuania

Following the Lithuanian military conquests of the fourteenth century, the Rus' and other inhabitants (including Jews) of most of the Ukrainian lands came under the jurisdiction of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. At the same time, Poland consolidated its rule over Galicia and its diverse inhabitants.

Small numbers of Jews from Poland and Lithuania — where they had settled after fleeing persecution in the Rhineland region in the thirteenth century — began to migrate to the Ukrainian lands incorporated into the Grand Duchy. Three of the six Jewish urban communities in the Lithuanian Grand Duchy were located in Ukraine: Volodymyr, Lutsk, and Kyiv. According to one account, some Jews also owned landed property in rural areas around these cities — contrary to a widely-held understanding that Jews could not own land in Poland and Lithuania.

Read more...

Estimates suggest that in 1493 the population in the territory of Poland and Grand Duchy of Lithuania combined was 7.5 million — including 3.75 million Ruthenians (the ancestors or cultural predecessors of ethnic Ukrainians and Belarusians), 3.25 million Poles, and 0.5 million Lithuanians. Estimates of the number of Jews in Poland-Lithuania at this time range from 10,000 to 24,000.

After Grand Duke Vytautus had invited Karaites from Crimea to settle in Lithuania in the early fifteenth century, there were three distinct Jewish communities in the Duchy: Slavic-speaking Knaanic Jews, German-speaking Ashkenazi Jews, and Turkic-speaking Karaites. However, after the temporary expulsion of Jews from Lithuania in 1495, no Slavic-speaking Knaanic Jews remained in the Duchy. They had either converted to Orthodoxy or assimilated with the Ashkenazi Jews during their temporary exile in Poland.

As Orthodox Rus' inhabitants in the Grand Duchy were subjected to legal and social discrimination by the Catholic Lithuanian rulers, some responded by emigrating eastward to Orthodox Muscovite lands. The flight to the east of an increasing number of Rus' nobility, clergy, townspeople, and even peasants from Belarus and Ukraine was particularly evident during the sixteenth century.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 155; Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford and Portland, OR, 2010), vol. I, 11–12;

- Omeljan Pritsak, "The Pre-Ashkenazic Jews of Eastern Europe in Relation to the Khazars, the Rus' and the Lithuanians," in Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective, Peter Potichnyj & Howard Aster, eds. (Edmonton, 1988), 14;

- Iwo Pogonowski, Poland: A Historical Atlas (Dorset Press, 1989), 92;

- Judith Kalik, Movable Inn: The Rural Jewish Population of Minsk Guberniya in 1793-1914 (Berlin, De Gruyter Open Poland, 2018),19–21.

1490s–1578

By the end of the fifteenth century, Lviv became home to one of the largest of fifty-eight Jewish communities in the Kingdom of Poland. In 1578, approximately 1,500 Jews lived in Lviv, where there were two Jewish communities, one inside the town walls and one outside.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford and Portland, OR, 2010), vol. I, 11.

1449–1783

The Crimean Khanate

The Crimean population evolved from an amalgam of ethnic groups that inhabited the Crimea from ancient times, including Scythians, Goths, Alans, Huns, Greeks, Jews, Genoese, and Armenians. Most of Crimea's heterogeneous population had adopted Turkic languages and the Islamic faith. They came to be known as Tats — initially a derogatory term for Turkic speakers not considered of "pure" Turkic descent — which made the Crimean Tatars a distinctive group, different from other Tatars living in Central Asia.

Read more...

In broad human geography terms, the Crimean Khanate's estimated population of 500,000 consisted of two segments: the sedentary inhabitants of the southern third of the peninsula (including the coastal cities) and the nomadic groups, particularly the Nogay tribes that roamed in the Ukrainian steppe lands. Nogay Tatars who migrated to the Crimean Khanate in the mid-sixteenth century constituted 40 percent of its population.

Two distinct Jewish communities, both small, also had evolved in the Crimea during this period: the Crimean Jews, later known as Krymchaks (an indication they were considered indigenous to the Crimea), who adhered to rabbinic Judaism, and the Karaites, adherents of a sect that recognized the Hebrew Bible but rejected rabbinic Judaism, specifically, the Talmud. The ancestors of the Krymchaks likely included Hellenized Jews who had settled along the Black Sea in ancient times, augmented by Jews from the Byzantine empire, Genoa, Georgia, and other places. The Karaite sect, which flourished in the early medieval Jewish centers between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, had spread throughout the Middle East. Some Karaites settled in the Byzantine Empire in the twelfth century and then migrated to the Crimea, together with the Tatar conquerors, in the mid-thirteenth century.

Wars and intergroup conflict triggered further migrations. Karaites settled in Caffa/Kefe and Solkhat/Eski Kirim and, after the Ottoman conquest in 1475, in the mountaintop towns of Mangup Kale and Chufut-Kale (Çufut Qale). Some Karaites also migrated to several towns of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, including Kyiv, Lutsk (in Volhynia), and Halych (in Galicia). When Crimean Tatars captured and plundered Kyiv in 1482, many Jews were taken captive and brought to the Crimea, where some remained even after they were ransomed. When Jews were expelled from Kyiv and Lithuania in 1495, some Karaites from Lutsk took refuge in Chufut-Kale.

By the sixteenth century, the major Krymchak center had moved from Caffa/Kefe (today Feodosiia) to Qarasubazar (today Bilohirsk/Belogorsk). Qarasubazar remained the Tatar-speaking Jewish community's social and economic center for more than 300 years.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, This Blessed Land (Toronto 2014), 50–53;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 181–183;

- Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe (New York, 2015), 142;

- "Nogay Tatars," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (2014);

- Dan Shapira, "The First Jews of Ukraine," in Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry, Volume 26, Jews and Ukrainians, eds. Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Antony Polonsky (Oxford, 2014), 75–76;

- Golda Akhiezer, "Karaites," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1440–1590s

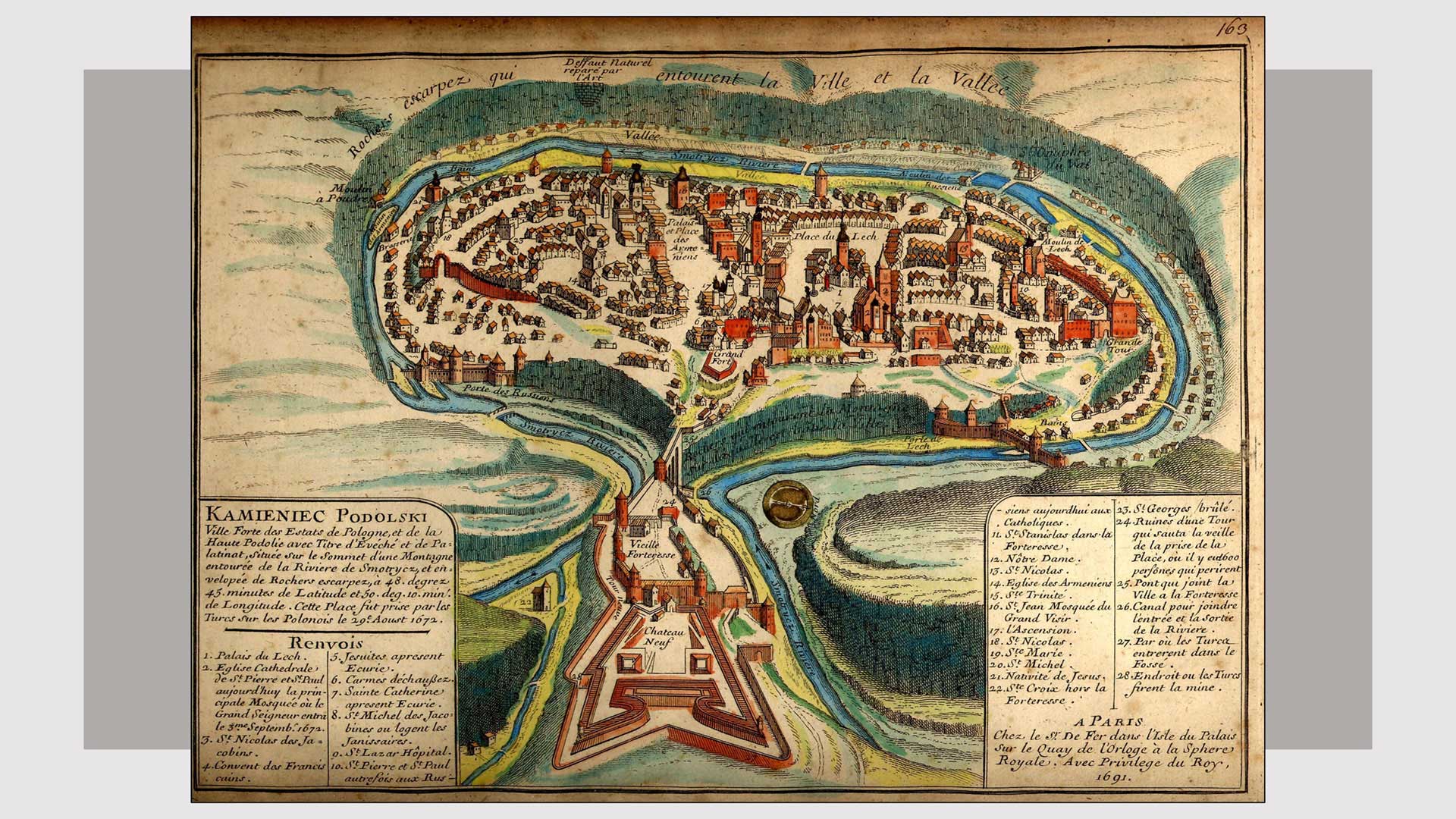

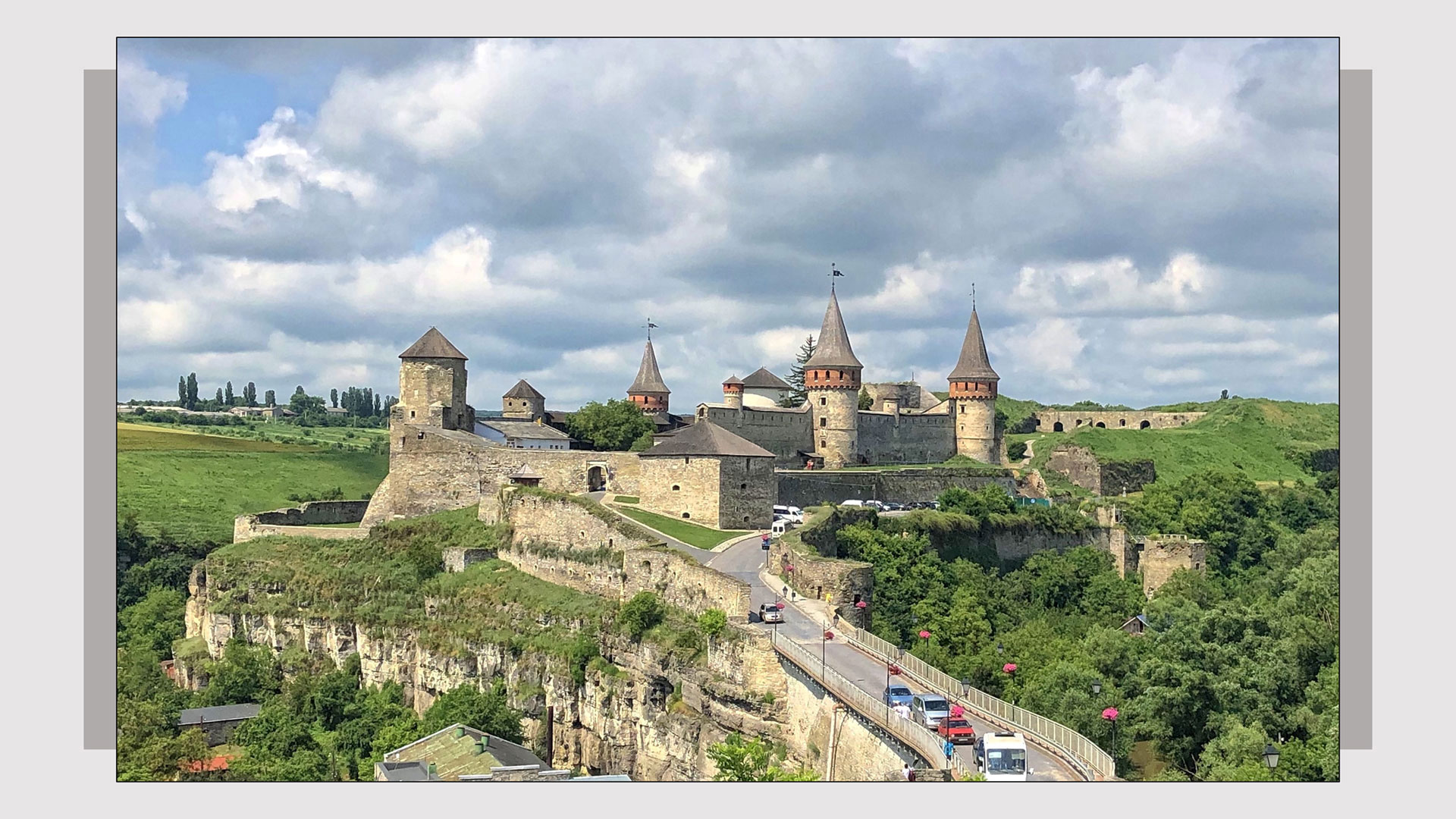

Profile of a Grand Duchy town: Kamianets-Podilskyi

Kamianets-Podilskyi experienced both the highs and lows of Ukrainian history before, during, and after this period. First mentioned as a Kyivan Rus' town in the eleventh century, the town was destroyed by Mongol invaders in 1241. In the 1430s, the town passed from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania to Polish rule. In 1463, it was proclaimed a royal city, granted duty-free status, and designated the capital of Podolia. During this period, residence rights in Kamianets-Podilskyi were restricted for Ukrainians and much more so for Jews.

Read more...

Under Polish rule, the town grew into a center of international trade and artisanry, second only to Lviv. However, the rights of its Ukrainian inhabitants were diminished, and in 1534 they were forced to live outside the city walls. Prohibition of Jewish settlement was even more severe. The first evidence of a Jewish presence in the town is implicit in laws promulgated in 1447 and later decrees, forbidding Jews to reside in the town for more than three days at a time. In 1598, after granting Jews the right of residence nine years earlier, the Polish King Sigismund III again prohibited Jews from settling in the town or its suburbs, and also from engaging in trade there. Jewish residents were forced to live in outlying villages, and visits to their hometown continued to be restricted to three days’ duration.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford and Portland, OR, 2010), vol. I, 83;

- Volodymyr Kubijovyč, "Kamianets-Podilskyi," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (article updated in 2010);

- Benyamin Lukin, "Kam'ianets'-Podil's'kyi," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).