1560s–1600s

The Christian Orthodox cultural revival of the early 1500s, evidenced in the emergence of schools and printing presses under Orthodox auspices, continued during this period. In part, the religious-cultural revival was a reaction to the inroads that Catholicism was making into Western Ukraine. It was also a reflection of the spirit of the times — including the Renaissance's validation of classical cultural models and the influence of the Protestant Reformation in the realm of education and intellectual discourse. More directly, the practical realization of the Orthodox cultural revival in western Ukraine was due to wealthy patrons, in particular Kostiantyn Vasyl Ostrozky.

Read more...

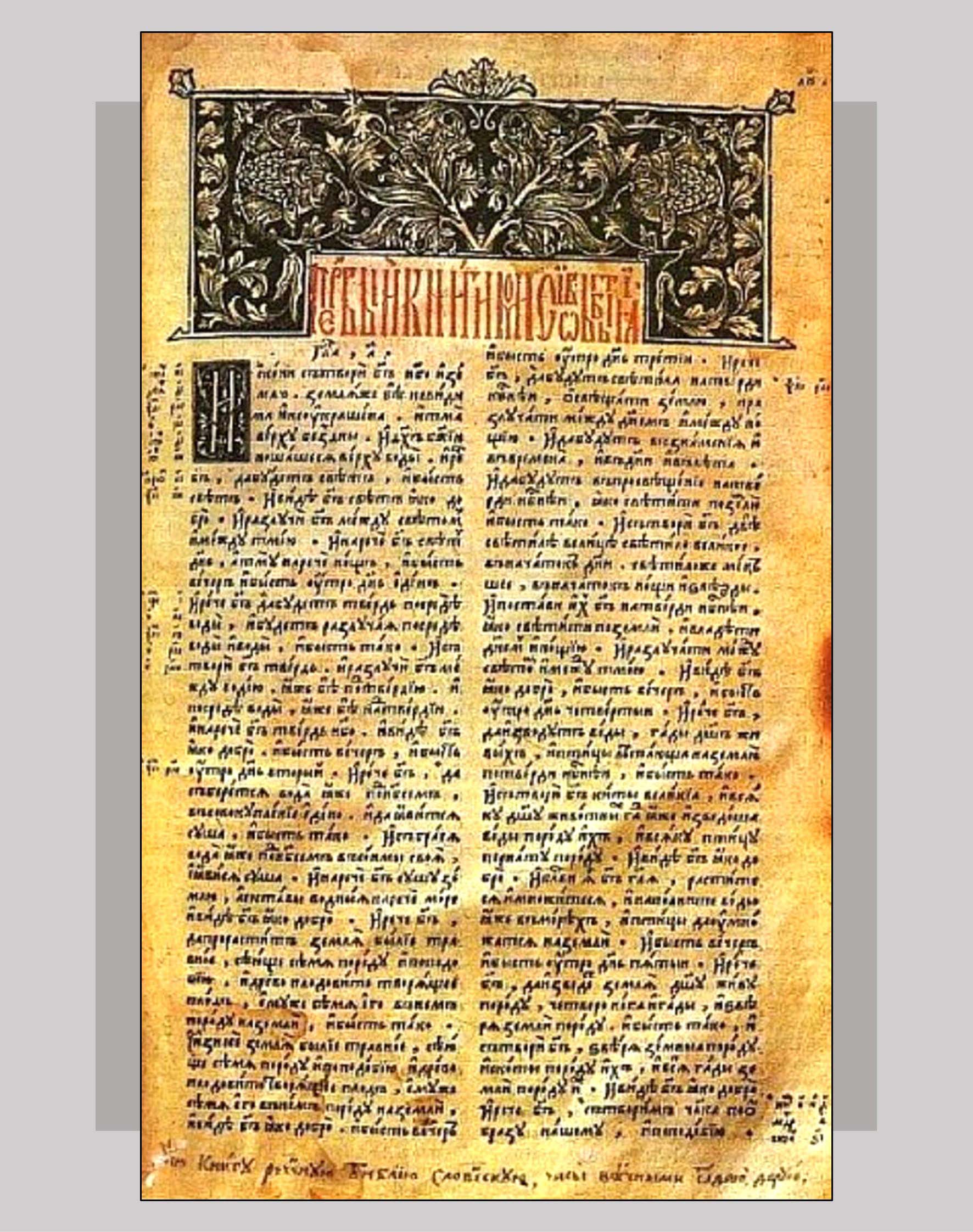

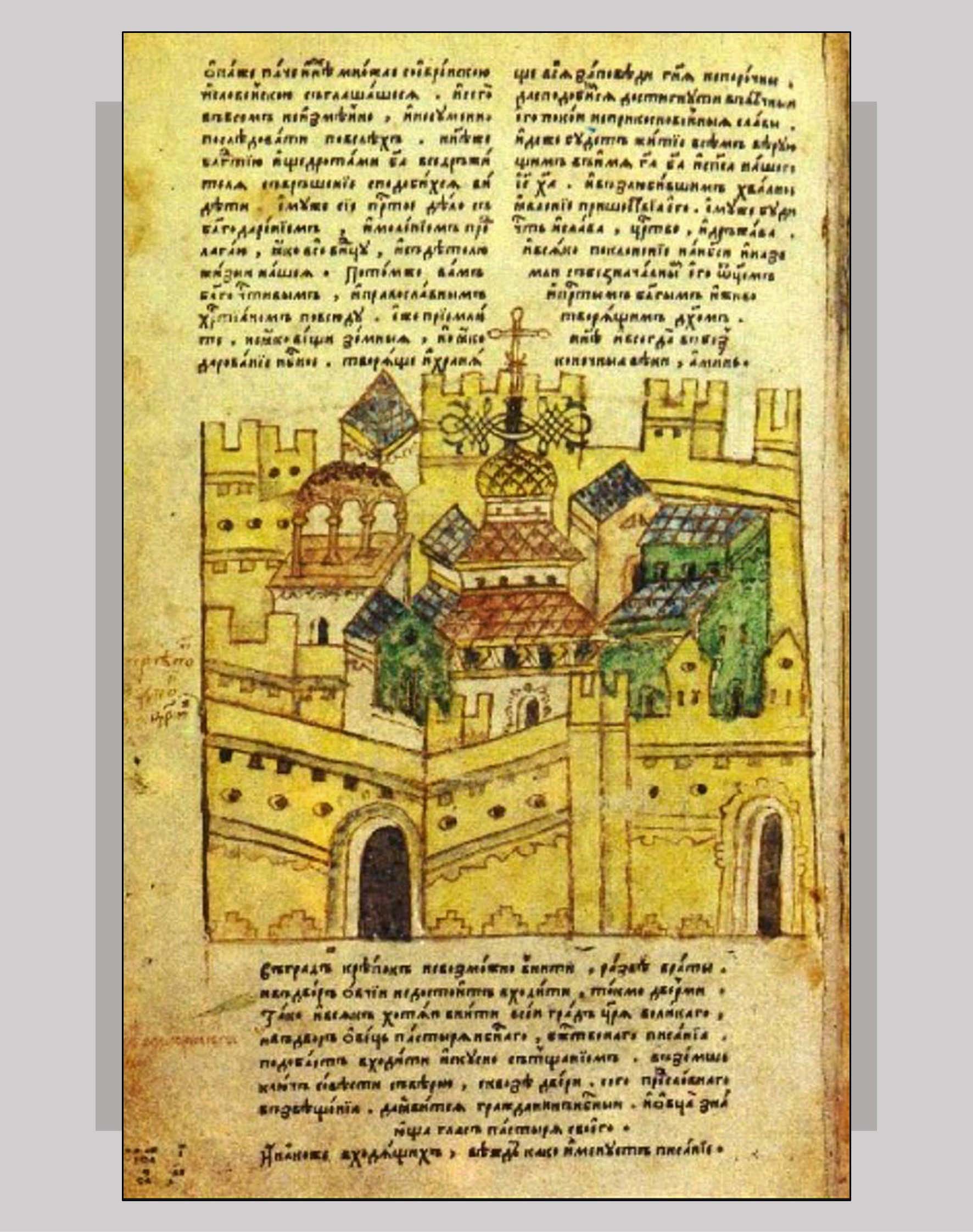

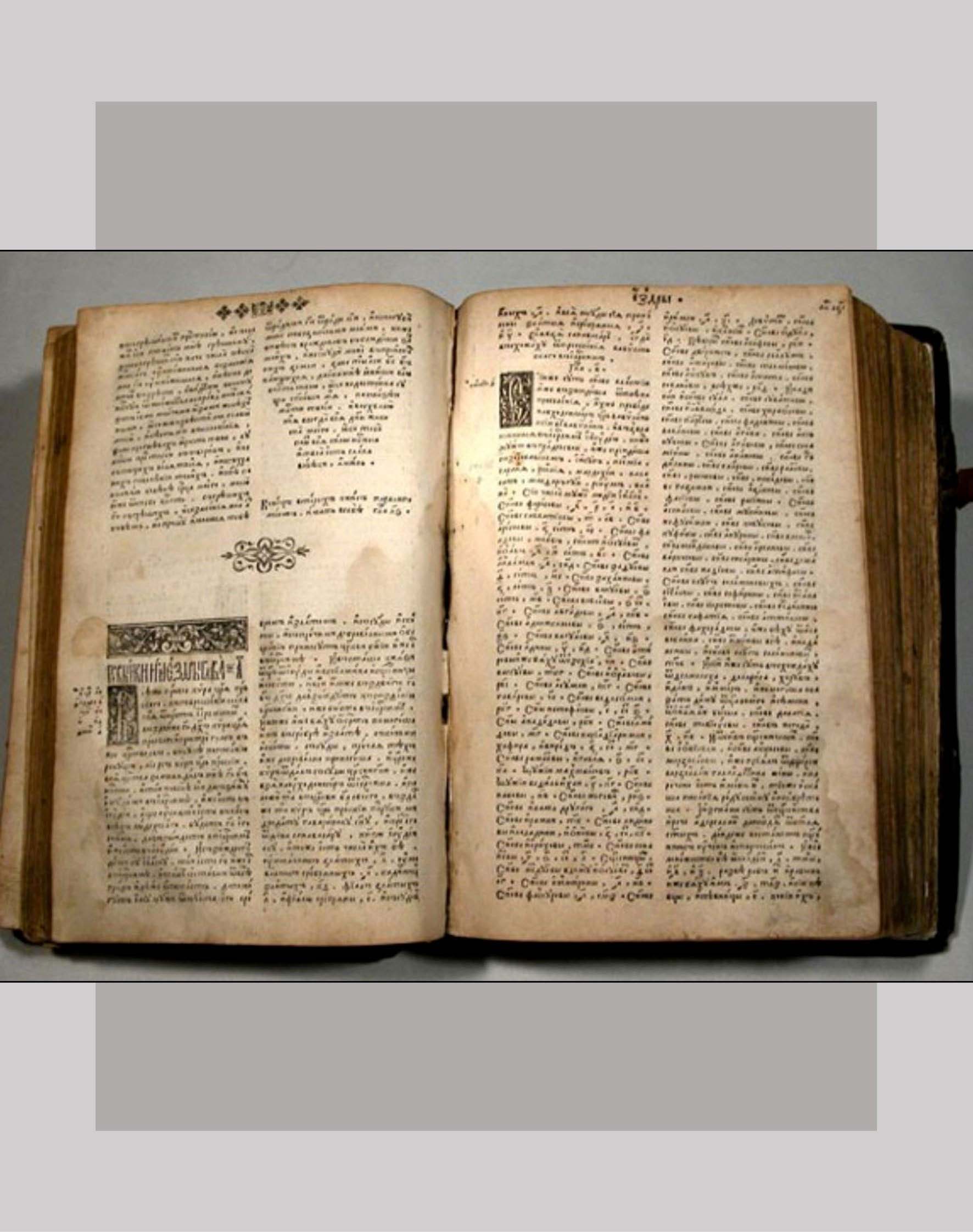

Volhynia, in particular, experienced a significant cultural and religious revival in the late 1570s. The principal benefactor of the Volhynian revival was the Rus’-Ukrainian nobleman, Kostiantyn Vasyl Ostrozky, reputed to be the wealthiest person in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, second only to the Polish king. Ostrozky established schools in several Volhynian towns; the best known, the Ostroh Academy (founded in 1576), became a bastion of Orthodoxy, with Greek as the language of instruction, with emphasis also on Latin and local Rus' culture. The college was renowned for its rich curriculum (including theology, philosophy, medicine, natural science, mathematics, astronomy, grammar, rhetoric, and logic) and choral singing. Ostrozky also founded a printing press in Ostroh, which operated from 1578 to 1612 and sponsored the publication of the Ostroh Bible (1581) — the first complete text of the Old and New Testaments and the first three books of the Maccabees in Church Slavonic, translated from the Greek by a group of Ostroh academy scholars. Following the establishment of a rival Jesuit college in Ostroh in 1624, the Ostroh Academy went into decline and was closed by 1636.

Ostrozky maintained close contact with other strong defenders of the Orthodox faith, such as the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood and the Orthodox Bishop of Lviv Hedeon Balaban. The brotherhoods (a centuries-old phenomenon of fraternities affiliated with individual churches) assumed a historical role by counteracting Polonization, Catholic (particularly Jesuit) expansion into Ukrainian lands, and later, conversions to the Uniate Church. The brotherhoods, whose members were predominantly burghers, acquired a secular character and often opposed the authoritarian and, at times, corrupt practices of the clergy. Ostrozky also had strong connections with Ukrainian Cossacks, for which he was condemned by the Polish nobility.

sources and related

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 165, 169;

- "Ostrozky, Kostiantyn Vasyl," (1993), "Brotherhoods," (1984), Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine.

Related

Chapter 5.4 1700s–1870s

1582–1609

The largest synagogue in Lviv was built in 1582–95 with funds provided by the merchant Izak Nachmanowicz. The synagogue was later named "Di Goldene Royz" (the Golden Rose) in honour of Nachmanowicz's daughter-in-law Rosa, an educated woman actively engaged in community charity work and in her husband's business after his death. According to legend, she ransomed the synagogue in 1609 from the Jesuits who had laid claim to it.

Read more...

The synagogue was also known as the Turei Zahav synagogue in honour of Rabbi David ha-Levi Segal (1586-1667), whose most famous work, a commentary on Jewish law, was titled Turei Zahav (Pillars of Gold). By traditional convention, great rabbis are often referred to by the titles of their books rather than their given names.

In 1941, the German occupiers plundered the religious objects in the synagogue and in 1943 destroyed the building, leaving only remnants of the north wall. The remains of the synagogue, neglected for decades, were integrated into a Jewish memorial complex, the Space of Synagogues, in 2016.

sources

- Vul. Fedorova, 27 – former Golden Rose Synagogue (Taz, Turey Zahav).

1589

The synagogue in Sharhorod (Vinnytsia Oblast) was built as part of the town's defensive system. The Ottoman Turks later transformed it into a mosque when they occupied Podolia (1672–1699). After their withdrawal, Jews restored the building to its original function. Under Soviet rule after World War II, the building was used as a juice factory.

sources

- The Bezalel Narkiss Index of Jewish Art, The Center for Jewish Art, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

1596

Union of Brest

The Union of Brest (Berestia) agreement was proclaimed between the Ruthenian (Ukrainian-Belarusian) Orthodox church in Poland-Lithuania and the Holy See, leading to the creation of the Uniate Church (later renamed the Greek Catholic Church).

The agreement, signed by the Kyivan metropolitan and several bishops, signalled a break with the Patriarch of Constantinople. It brought part of the Kyiv Orthodox metropolitanate under the jurisdiction of the Pope in Rome while maintaining the Eastern-rite liturgy and practices. Practices retained include the use of Church Slavonic instead of Latin and the possibility of married men being ordained as priests.

Read more...

Various developments had converged to bring about the Union of Brest, including the Turkish conquest of the seat of the patriarch of Constantinople in 1453, the creation of the Moscow patriarchate in 1589, and Protestant influences. Ruthenian supporters of the plan had also hoped to gain ecclesiastical benefits from the Union and an end to the Polonization of the Ruthenian upper classes. However, some Orthodox viewed it as a Polish ploy to impose Catholicism on the Eastern Christian Ukrainian populace. The influential Ukrainian nobleman, Kostiantyn Vasyl Ostrozky, who had played a central role in negotiating the agreement, later led the resistance to it.

The Union of Brest split the Ruthenian church and the faithful in two and led to a long and bitter domestic struggle. It also became a key issue in the political and social conflict between the Cossacks and the Poles and in the Pereiaslav Treaty of 1654 with Muscovy.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 174–75;

- Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe (New York, 2015), 360;

- "Church Union of Berestia," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1984).

1550s–1650s

During this period, anonymous lyrical epic tales known as dumy (sing. duma) were composed, highlighting the impact of the Tatar attacks and slave trade on Ukrainians. They include laments on the fate of the captives, descriptions of attempts to escape slavery, and praise for those who saved and freed them or who died in the struggle against the captors. The folk heroes of the dumy are the Cossacks who fought the Tatars and Turks, undertook expeditions against the Ottomans, and at times freed slaves.

After the destruction of the Zaporozhian Sich and the Russian conquest of most of Ukraine, the romanticized and idealized Cossack became an especially popular figure — ubiquitous in Ukrainian art, literature, and drama.

Read more...

Negative depictions of Jews figure prominently in two dumy: "Duma of the Oppression of Ukraine by Jewish Leaseholders" and the "Duma of the Battle of Korsun." Prominent Ukrainian figures Ivan Franko and Mykhailo Hrushevsky and scholars today consider that the anti-Jewish depictions in these dumy reflect nineteenth-century alterations to the original seventeenth-century versions, which in turn influenced the construction of negative stereotypes of Jews in nineteenth-century Ukrainian historical fiction.

sources

- Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe (New York, 2015), 75;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 185;

- Mykola Mushynka, "Kozak-Mamai," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1989);

- Myroslav Shkandrij, Jews in Ukrainian Literature. Representation and Identity (New Haven, 2009), 14–19.

1629

King Sigismund III gave Jews permission to build the stone synagogue in Lutsk on the condition that they provide for the placement of guns on top of the synagogue on all four sides and procure, at their own expense, a reliable cannon for the defence of the city. Partially destroyed in 1942, the synagogue was restored in the 1970s. It is now used as a sports club.

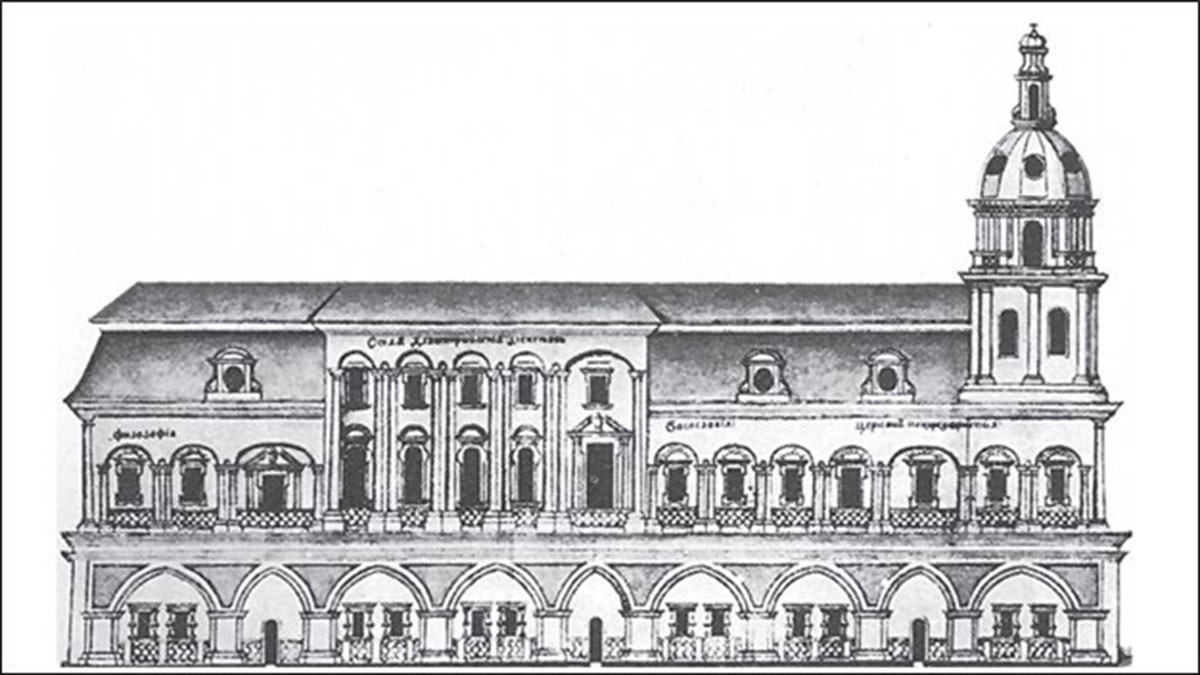

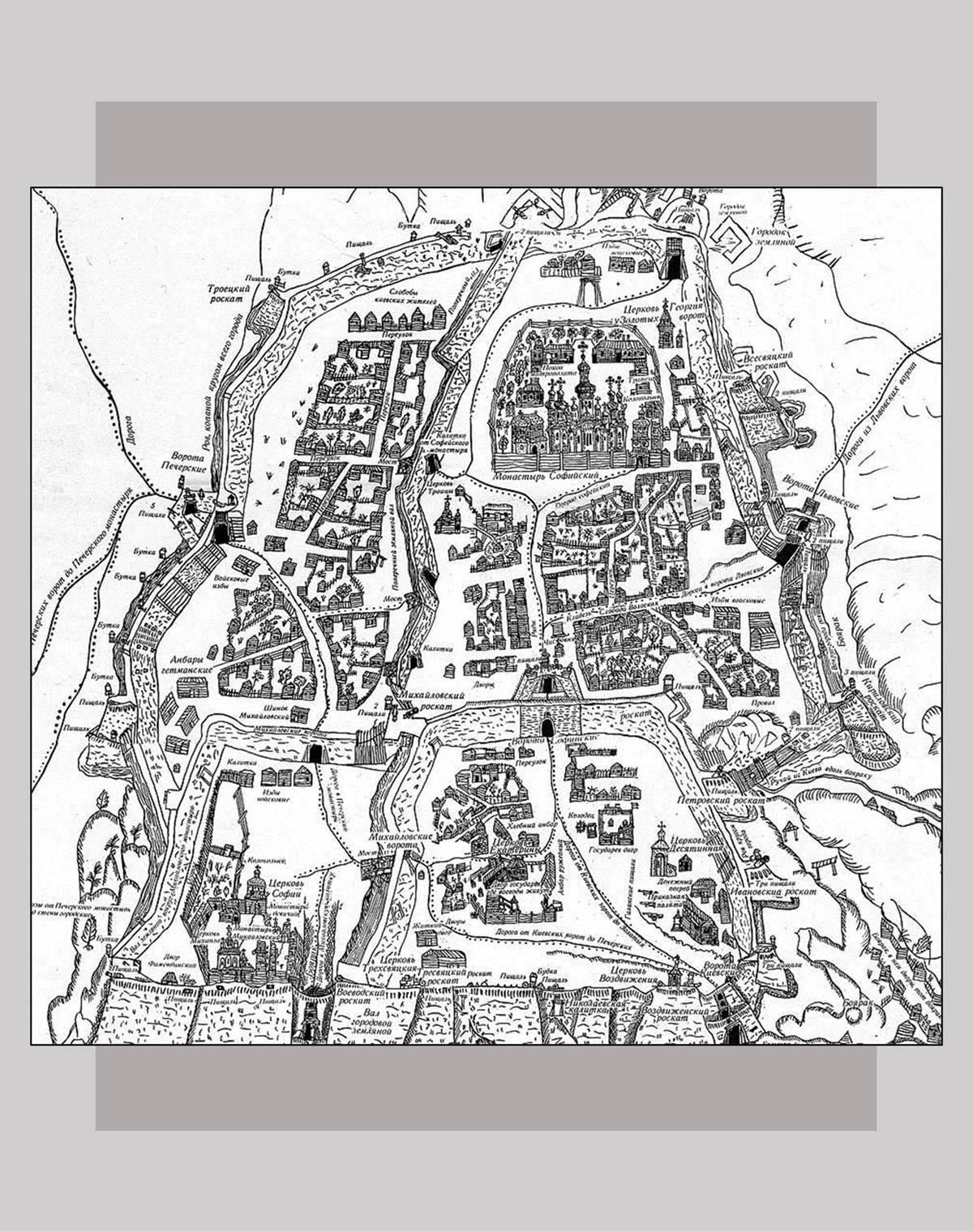

1632–1646

Metropolitan Petro Mohyla of Kyiv established the Kyivan College (future Kyiv Mohyla Academy), the most important center of learning and scholarship throughout the Orthodox world. He also reformed his church along the lines of the Catholic Reformation, restored Rus’-era churches, and presided over the drafting of the first Orthodox Confession of faith.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Ukraine: An Illustrated History (Toronto, Second Edition, 2007), 80;

- Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe (New York, 2015), 93–94, 369.

1653

Sefer Yeven Metzulah, the first and best known of several Hebrew chronicles of the 1648–49 massacres of Jews during the Khmelnytsky Uprising, was published in Hebrew in Venice. It was written shortly after the massacres by Ostroh native and eyewitness Nathan Hannover; it was then produced in several Yiddish translations, the first in 1677 and in other languages since then. Hannover's account contains graphic descriptions of brutality, which influenced perceptions of the Cossacks as savage perpetrators of anti-Jewish violence. Noteworthy at the same time is Hannover's remarkably sophisticated and sympathetic treatment of the plight of the Ukrainians as context for the horrific violence described.

Read more...

According to recent scholarship, the early chronicles significantly overstated the number of Jewish victims and the extent of the devastation of communities. Some claim that Hannover adopted tropes and stories drawn from earlier literature on Jewish martyrology. Others have observed that his primary purpose was not only to chronicle the tragic events but also to inspire prayers for the martyrs and to gather aid for the refugees and the restoration of communities. Ultimately, the impact of the violence (and the chronicles) on Jewish memory has been deep and enduring. The events inspired liturgical compositions, an annual day of fasting (20th of the month of Sivan), and songs to commemorate the martyrs, including a Yiddish ballad composed in 1649, entitled "The Misfortunes of the Holy Communities in the Land of Ukraine." Khmelnytsky is perceived very differently in Ukrainian historical memory.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford and Portland, OR, 2010), vol. I, 30;

- Moshe Rosman, "Dubno in the wake of Khmel'nyts'kyi," in Jewish History, vol. 17: 239–255 (2003);

- Shaul Stampfer, "Gzeyres Takh Vetat," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1650s–1660s

The Polish King Jan II Kazimierz permitted Jews who had been forced to convert to Orthodoxy during the Khmelnytsky Uprising to revert to Judaism. This measure was exceptional, as conversion or reversion to Judaism was treated by the Church as apostasy and, until 1768, punishable by death.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford and Portland, OR, 2010), vol. I, 23.

1665–1670

Shabbetai Zvi's claim that he was the Messiah was met with wide enthusiasm across the Jewish world, including in Ukrainian lands, though there were also many skeptics. The messianic pretender had argued that the 1648 massacres in Ukraine were the prophesied "birth pangs of the Messiah," marking the beginning of the era of redemption. Convinced representatives of Jewish communities, including Lviv, travelled to meet him when he was imprisoned in Turkey. Their enthusiasm turned to disillusionment when, under threat of death by Turkish authorities, Shabbetai Zvi converted to Islam in 1666. In response, Jewish communal authorities in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth began in 1670 to issue bans of excommunication against persistent adherents of Sabbatianism.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford and Portland, OR, 2010), vol. I, 138, 141.

- Michał Galas, "Sabbatianism," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1669

A voluminous polemical-religious tract in Ukrainian, entitled Mesiia pravdyvyi (The True Messiah), which included a focus on Jews and Judaism, was published in Kyiv. The tract was written by Ioanikii Galiatovsky, a prominent Ukrainian Orthodox church leader and head of the Kyivan Mohyla College. Inspired by the polemics against the false Jewish messiah Shabbetai Zvi, the author noted that "the Jewish heresy raised its head in Volhynia, Podolia, in all the provinces of Little Russia... The foolish Jews rejoiced and expected that the messiah would take them to Jerusalem on a cloud." This tract also contains the first Orthodox reference to the blood libel, likely reflecting Western Catholic influence.

sources and related

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford and Portland, OR, 2010), vol. I, 139;

- Judith Kalik, "Jews, Orthodox and Uniates in the Ruthenian lands," in Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry, Volume 26, Jews and Ukrainians, eds. Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Antony Polonsky (Oxford, 2014), 141–42.

Related

Chapter 4.5 1740s–1750s

1672–1720s

In Podolia, then under Ottoman rule (1672–1699), several prominent individuals and even communal rabbis continued to profess Sabbatian beliefs openly. Żółkiew/Zhovkva was a principal center for Sabbatian fervour, prompting rabbinical bans of excommunication against members of the sect in 1688, 1716, and 1722. Other towns in which Sabbatianism persisted include Buczacz/Buchach, Busk, Gliniany/Hlyniany, Horodenka, Nadwórna/Nadvirna, Podhajce/Pidhaitsi, Rohatyn, and Satanów/Sataniv.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford and Portland, OR, 2010), vol. I, 138, 141;

- Stefan Gąsiorowski, "Zhovkva," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010);

- Michał Galas, "Sabbatianism," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1674

Monks of the Kyivan Cave Monastery published Synopsis, a highly influential history textbook that argued for religious, dynastic, and ethnonational unity of Eastern Slavs in the face of threats from Poland and the Ottoman Empire. The textbook, attributed to Kyivan Academy churchman and scholar Innokentii Gizel (but further elaborated after his death), presented Muscovy as the successor state of Kyivan Rus'. Scholars suggest that his aim was to enlist the protection and help of the Muscovite tsar by connecting Kyiv with Muscovy. Paradoxically, this work by a Kyivan cleric became a springboard for Russian imperial historiography and was adopted as a basic history textbook in schools throughout the Russian Empire, reprinted nineteen times by 1836. As noted by historian Zenon Kohut, this most popular but Russian-oriented indigenous history of the Eastern Slavs completely ignores the Cossack wars, Bohdan Khmelnytsky, and the mid-seventeenth century massacres of Jews.

sources

- Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe (New York, 2015), 75–77, 360;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Ukraine: An Illustrated History (Toronto, Second Edition, 2007), 106;

- Zenon E. Kohut, "The Khmelnytsky Uprising, the image of Jews, and the shaping of Ukrainian historical memory," Jewish History, vol. 17 (2003), 142–143.

1686–1770

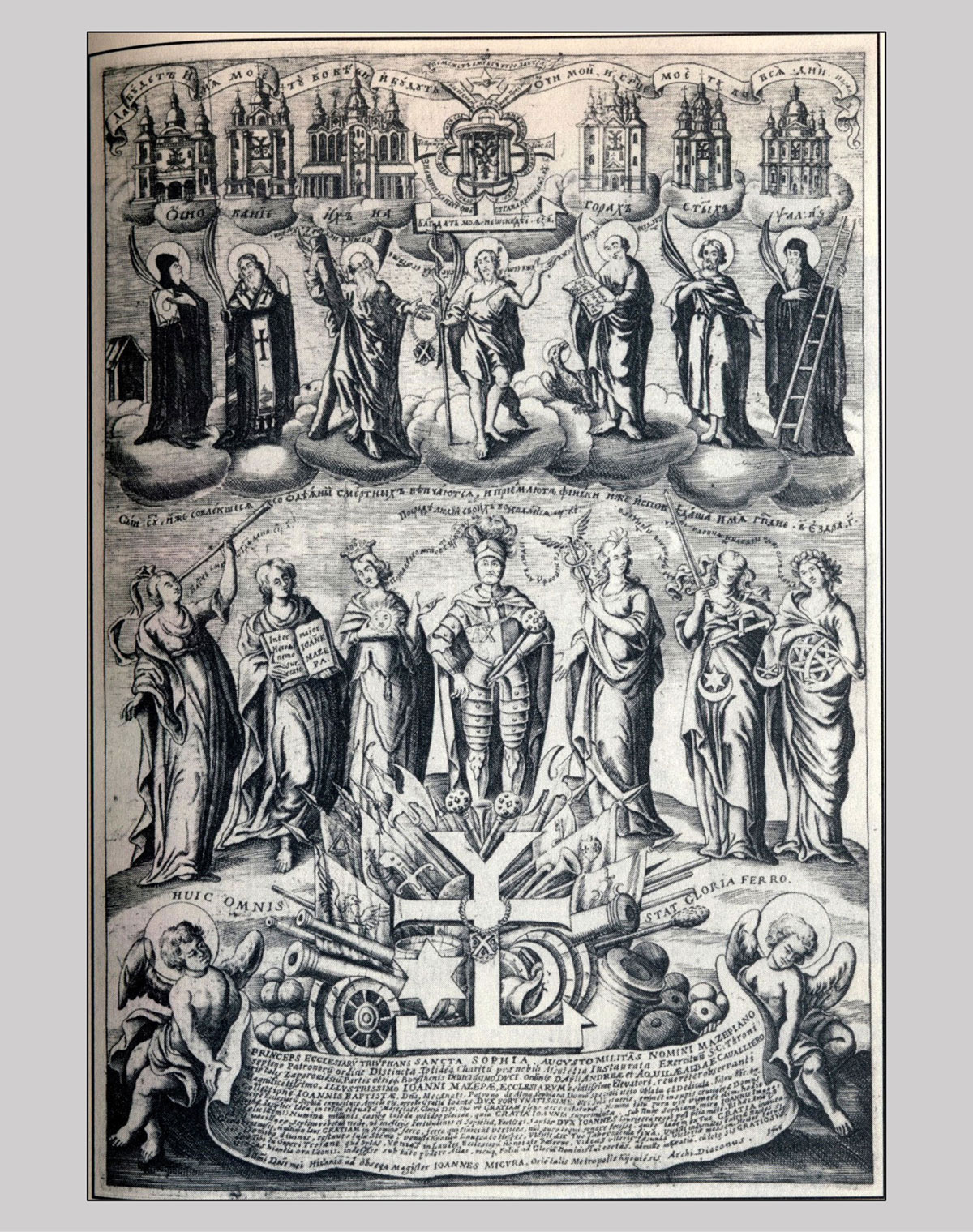

During the first thirteen years (1687–1700) of Ivan Mazepa's rule of the Cossack Hetmanate, the Orthodox Church benefitted from social stability, economic growth, and extensive support for cultural activity. A notable feature of this period was the construction or reconstruction of several Orthodox churches and monastery complexes in a style that came to be known as Ukrainian Cossack Baroque.

Ethnic Ukrainians dominated ecclesiastical and intellectual life in eighteenth-century Russia. The Kyivan Caves Monastery had its own printing press and an influential school of icon-painting, and Ukrainians introduced polyphony into Orthodox music.

Read more...

Other developments, however, undermined the status of the Orthodox Church in Ukraine. In 1686, the Orthodox Metropolitanate of Kyiv was made jurisdictionally subordinate to the Russian Orthodox Church in Moscow instead of the ecumenical patriarch in Constantinople. By 1770, the title of the Metropolitan of Kyiv became largely honorific, following tsarist reforms that transformed the Orthodox Church into an instrument of the state. The process of subjecting the Orthodox Church to state interference had begun in 1721 when Tsar Peter I abolished the office of patriarch and replaced it with a collegium known as the Holy Synod, headed by a secular official (the Chief Procurator), who reported directly to the tsar.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Ukraine: An Illustrated History (Toronto, Second Edition, 2007), 107, 140.

- John-Paul Himka, Ten Turning Points: A Brief History of Ukraine.

1692–1800s

One hundred and twenty years after the introduction of Slavonic typography in Lviv, the first Hebrew press in Ukrainian lands was opened in 1692 in Żółkiew/Zhovkva in Galicia. Until the 1780s, Zhovkva was the only place in Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth where Jewish books were printed. The printing house was established by Uri Feibush (Phoebus) Halevi (also known as Uri Witzenhausen), a Jewish printer from Amsterdam, and was maintained by his descendants for generations, first in Zhovkva and later in Lviv. Zhovkva's Hebrew publications are noteworthy for an element of pretense on their title pages. They indicated that the font used was "Amsterdam" in large letters to link the publications to the famous Hebrew press that flourished in Amsterdam at the time; the actual place of publication "Żółkiew" was printed in much smaller letters. The virtual monopoly that Zhovkva enjoyed in Hebrew printing in the course of the 1700s waned as Hebrew printing houses emerged in Lutsk, Lviv, and Korets in the 1780s; and in Dubno, Polonne, Slavuta, and Ostroh in the 1790s.

sources

- Zeev Gries, "Printing and Publishing: Printing and Publishing before 1800," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1700s

In the eighteenth century, Chufut-Kale in the Crimea became a major Karaite cultural center, with Hebrew presses and efforts to create a Karaite Turkic literary language, first using the Hebrew alphabet and later the Russian and Latin (Polish) alphabets. Due to the limited market of the small Karaite community, most of these presses were short-lived.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 183.

1730s–1740s

Attacks on manorial estates by small Robin Hood-like bands, whose members were called opryshky, became more widespread in the Carpathian mountain region during this period, though the phenomenon began a century earlier. Consisting of discontented peasants, sheepherders, and at times resisters of conscription, these bands looted the property of landowners and sometimes distributed the spoils to the poor peasantry. Their legendary deeds under their most famous leader, Oleksa Dovbush, were romanticized in local folklore and entered Jewish folklore. Both Ukrainian and Jewish folklores include tales about encounters between the two larger-than-life contemporary figures who roamed the Carpathian Mountains, Dovbush and the Ba'al Shem Tov (acronym, "the Besht"), the legendary Jewish holy man whose teachings inspired the Hasidic movement. According to a Hasidic legend, the Besht on one occasion sheltered Dovbush from pursuing authorities; to express his gratitude, Dovbush gave the Besht a prized pipe.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 311–312;

- Larisa Fialkova, "Oleksa Dovbush: An Alternative Biography of the Ukrainian Hero Based on Jewish Sources," Fabula 52 (1/2) (2011): 92–108;

- Boris Czerny, Contes et récits juifs et ukrainiens du pays houtsoule (Editions Petra, Paris 2018), 115–116.

1742–1790s

Israel ben Eliezer, better known as the Ba'al Shem Tov (lit. "Master of the Good Name," acronym: "the Besht") — a charismatic healer, miracle worker, and religious mystic who inspired the founding of the Hasidic movement — was invited to settle in Medzhybizh as the resident kabbalist, healer, and leader of the beit midrash (house of study). Legends describe the Besht's life prior to coming to Medzhybizh as a wandering preacher and healer in Podolia — communing with God and nature in the Carpathian Mountains and learning the art of herbal remedies from local peasants.

Archival documents relating to his years in Medzhybizh indicate that he was a respected member of the local Jewish community, not a rebel against the established religious and social order, as depicted in some accounts. On his death in 1760, the Besht left behind an intimate circle of followers. It was they who were responsible for the emergence of Hasidism as a movement and its rapid expansion after 1772.

Read more...

Writings by his disciples that describe his teachings make salient that his innovation lay in revitalizing traditional religious practice by infusing it with spirituality, the expression of joy in worship and daily living, the validation of common folk, and devotion to a charismatic spiritual leader (tzadik, or rebbe). As noted by the scholar Ada Rapoport-Albert: "Hasidism… fused together two diametrically opposed poles of human experience: intensely personal, reclusive mystical flight from the world, and robust involvement in mundane human affairs."

Ukraine has been called the "cradle of Hasidism" because the movement originated in and flourished on Ukrainian lands. Its founders initially encountered fierce opposition from established rabbinic authorities (referred to as misnagdim or "opponents"), in particular from the venerated Gaon of Vilna. The strong negative reaction may be attributed in part to the Jewish world's traumatic experience with messianic pretenders and what was perceived as vulgarization of the Kabbalah, unseemly over-enthusiastic modes of worship, and the discounting of textual knowledge. However, the emergence of several charismatic Hasidic leaders with compelling yet reassuring messages paved the way for the eventual wide acceptance and spread of Hasidism across the Pale of Settlement and beyond. These leaders include Menahem Nahum of Chornobyl (1730–1797), Shneur Zalman of Liady (1745–1813), the founder of Chabad Hasidism, Levi Yitzhak of Berdychiv (1740–1810), and Nahman of Bratslav (1772–1810).

sources and related

- Moshe Rosman, "Ba'al Shem Tov," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010);

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford and Portland, OR, 2010), vol. I, 151–52, 154, 156.

1756–1760

Ya'akov (Jakub) Frank, a messianic pretender born in Podolia, was excommunicated together with his closest followers by a rabbinical assembly convened in Brody. The excommunication was prompted by the heretical doctrines he preached (such as "purification through transgression") and the disturbing behaviour he encouraged (including orgiastic promiscuity), which defied Jewish religious prohibitions.

After the Council of Lands confirmed the ban, the rabbinic establishment turned to the Roman Catholic Church hierarchy for support in extirpating this heresy. Instead, the clergy was persuaded by Frank's followers that the real reason the Jews were persecuting them was the affinity of the Frankist creed to Christian beliefs. A staged disputation ensued, organized in 1757 by the Catholic Bishop of Kamianets-Podilskyi, Mikołaj Dembowski, between the Frankists and forty rabbis, compelled to attend under threat of corporal punishment. Unsurprisingly, the Frankists were declared victorious, and Bishop Dembowski ordered the burning of the Talmud in Lviv, where he had become archbishop. At a second disputation, held in Lviv in 1759, the Frankists again highlighted the similarity of their beliefs to those of Christianity. However, they distanced themselves from attempts to prove that the Talmud required that Jews use Christian blood for ritual purposes.

Read more...

As a result of the disputations, the Frankists came to be treated as candidates for conversion to Catholicism. Frank and approximately 600 of his followers converted in Lviv with considerable fanfare immediately after the second disputation; over a thousand others converted the following year. However, it soon became apparent that Frank's conversion was part of a more grandiose messianic plan. Frank was arrested and convicted of heresy by a church tribunal in Warsaw and imprisoned in the monastery of Częstochowa, even as many of his followers entered the ranks of the Polish Catholic nobility.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford and Portland, OR, 2010), vol. I, 148–149;

- Pawel Maciejko, "Frankism," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).