1772–1815

While the 1781 Serfdom Patent, issued by Joseph II, aimed to abolish aspects of the traditional serfdom system and enhance fundamental civil liberties for the serfs, it was enforced differently in the various Habsburg lands. Serfdom, which was not abolished in the Empire until 1848, profoundly shaped the Galician environment economically, socially, culturally, and politically. It left the region economically backward and impoverished. Poverty was prevalent also among Galicia’s Jewish population, as described in an official report prepared by Prince Wenzel Anton.

Read more...

Joseph II's reforms gave Jews access to educational opportunities and new sources of livelihood, such as agriculture, transportation, crafts, and manufacturing. They were also granted the right to own and pass on land to children. However, the prohibition of leasing rural landholdings, mills, and inns was maintained, and only those Jews who personally worked the land were to be tolerated in rural areas. Moreover, a number of the economically beneficial reforms were only partially implemented in Galicia.

Widespread poverty aggravated social antagonisms, in particular the landlord-peasant relationship based on the coercion of labour-rents from the peasantry. Polish gentry owned most of the landed estates in Galicia and were politically powerful. There was also a substantial Polish peasant population, mainly concentrated in western Galicia, and Polish inhabitants in the larger cities, including artisans, merchants, and professionals. Ukrainians (then known as Ruthenians) were primarily a peasant society, with a thin layer of clerical and (by the 1840s) secular intelligentsia. Jews occupied intermediary positions in the feudal economy and the emerging money economy, the latter remaining marginal until the 1860s.

An official report on conditions in the newly acquired Austrian province of Galicia — prepared for Empress Maria Theresa by Prince Wenzel Anton von Kaunitz-Rietberg — found that Galician Jews were dependent on the production of the peasantry for their livelihood. The report also stated that "taken as a whole, they [the Jews] are very poor and merely a sponge that the clergy and nobility squeeze." An Austrian government investigation in 1815 reported that around one-third of the Jewish population in Galicia was composed of Luftmenschen, people whose only source of income was irregular, odd jobs. Impoverishment motivated many Galician Jews to emigrate to Hungary, the Romanian principalities, the Kingdom of Poland, and eventually Western Europe and America.

sources and related

- John-Paul Himka, "Ukrainian-Jewish Antagonism in Galician Countryside During the Late Nineteenth Century," in Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective, Peter Potichnyj & Howard Aster, eds. (Edmonton, 1988), 119;

- John-Paul Himka, "Dimensions of a Triangle: Polish-Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Austrian Galicia," Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry, 12, Israel Bartal & Antony Polonsky, eds. (London/Portland, 1999), 27–29;

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. I, 256.

Related

Chapter 5.6 1848–1860s

1820s–1840s

The town of Brody was Galicia's second-largest and the crownland's most important international trade junction at this time. Located near the Austrian–Russian frontier, the town prospered after being granted (in 1779) the status of a free port through which goods for export could pass without duty. Brody became a commercial and intellectual center, but its economy began to decline after 1848 when the new railway line to Odesa bypassed it. Its status as a free port was abolished in 1880. Many local Jewish wholesale merchants moved to other cities, notably Odesa, where they founded a choral synagogue (the Brody Shul) in 1840.

sources

- Börries Kuzmany, "Brody: Images Telling the Story," The Galitzianer (March 2017), 16.

1850s–1900s

Galicia

Oil exploration began in Galicia in the 1850s, turning the Boryslav and Drohobych region into one of the world's most productive oil fields. Jews were active in Galicia's small but vibrant oil industry from the beginning, including in the laborious work involved in primitive extraction methods and the refinement industry. The discovery of oil changed the course of the two towns' history and the development of their Jewish communities. Boryslav became a sprawling boom town, while Drohobych became the urban hub of the Galician oil belt.

sources

- Valerie Schatzker, The Jewish Oil Magnates of Galicia (Montreal & Kingston, 2015).

1850s–1900s

Bukovina

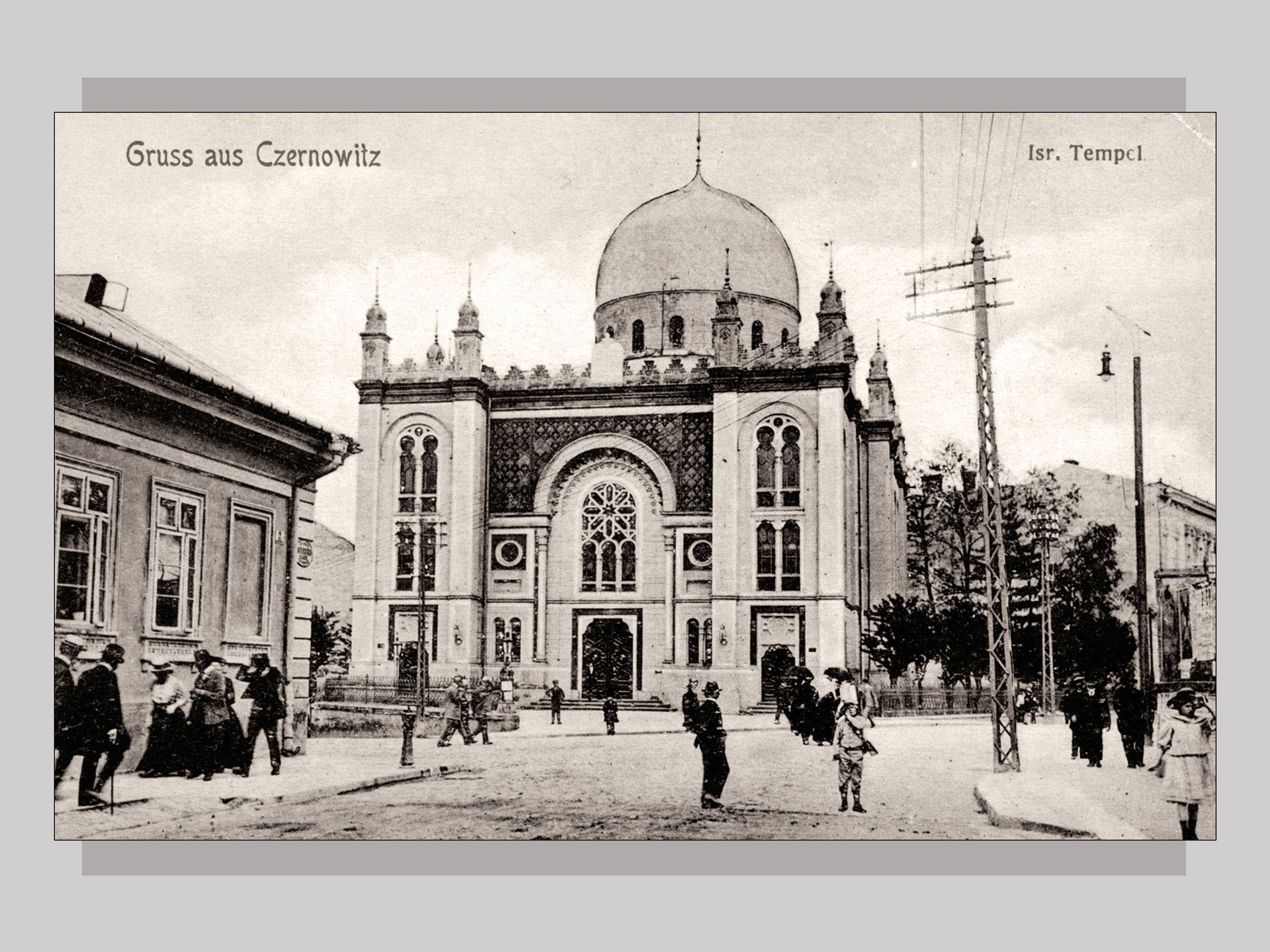

Bukovina's Jews resided mainly in Chernivtsi and smaller urban centers, where they played an important role in stimulating economic development. They were merchants, craftsmen, owners of industrial workshops, tavern owners, moneylenders, builders, and real estate owners. A relatively high proportion of Jews lived in the countryside, where they were either farmers or served as middlemen between the rural areas and urban markets.

sources

- Andrei Corbea-Hoisie, "Bucovina," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1870s–1900s

The Prosvita Society, which had concentrated on spreading education and culture among the Ukrainian masses in Galicia, began to engage in the economic domain, at times adopting an anti-Jewish stance in its publications. The Society helped organize stores, community warehouses, savings and loan banks, and agricultural and commercial cooperatives, often in competition with Jewish lenders and businesses. The Society was also preoccupied with the anti-alcohol campaign during this period, at times channelling hostility to the stereotype of the Jewish tavern-keeper.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 473;

- John-Paul Himka, Galician Villagers and the Ukrainian National Movement in the Nineteenth Century (Macmillan Press, 1988),126, 173, 188.

1890s

Pogroms in the early 1880s in the Russian Empire and impoverishment in Galicia drove many Jews from both Russia and Galicia to Transcarpathia, raising tensions with non-Jews there. The local population, experiencing a severe economic crisis, resented the "Galician" Jewish immigrants who did not till the soil as the local Jews did. In 1897, the assembly of parliamentary deputies from Transcarpathia, convened by the Bishop of Mukachevo, Iulii Firtsak, made several demands of the Hungarian government, including that it take measures to "limit the entry into Transcarpathia of usurers, tavern-keepers, and illegal merchants who mercilessly exploit the inhabitants."

sources

- Alexander Baran, "Jewish-Ukrainian Relations in Transcarpathia," in Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective, Peter Potichnyj & Howard Aster, eds. (Edmonton, 1988), 163–165.

1890s–1914

Galicia

Galicia remained largely rural and impoverished up to 1914. The abolition of serfdom in 1848 did not end the peasant-landlord conflict in either western or eastern Galicia, as large landed estates remained a feature of the agricultural system. In the early 1900s, about 40 percent of all land in Galicia was held in estates of more than 50 hectares. In contrast, 71 percent of all peasants in 1902 held less than five hectares, and 44 percent held less than two.

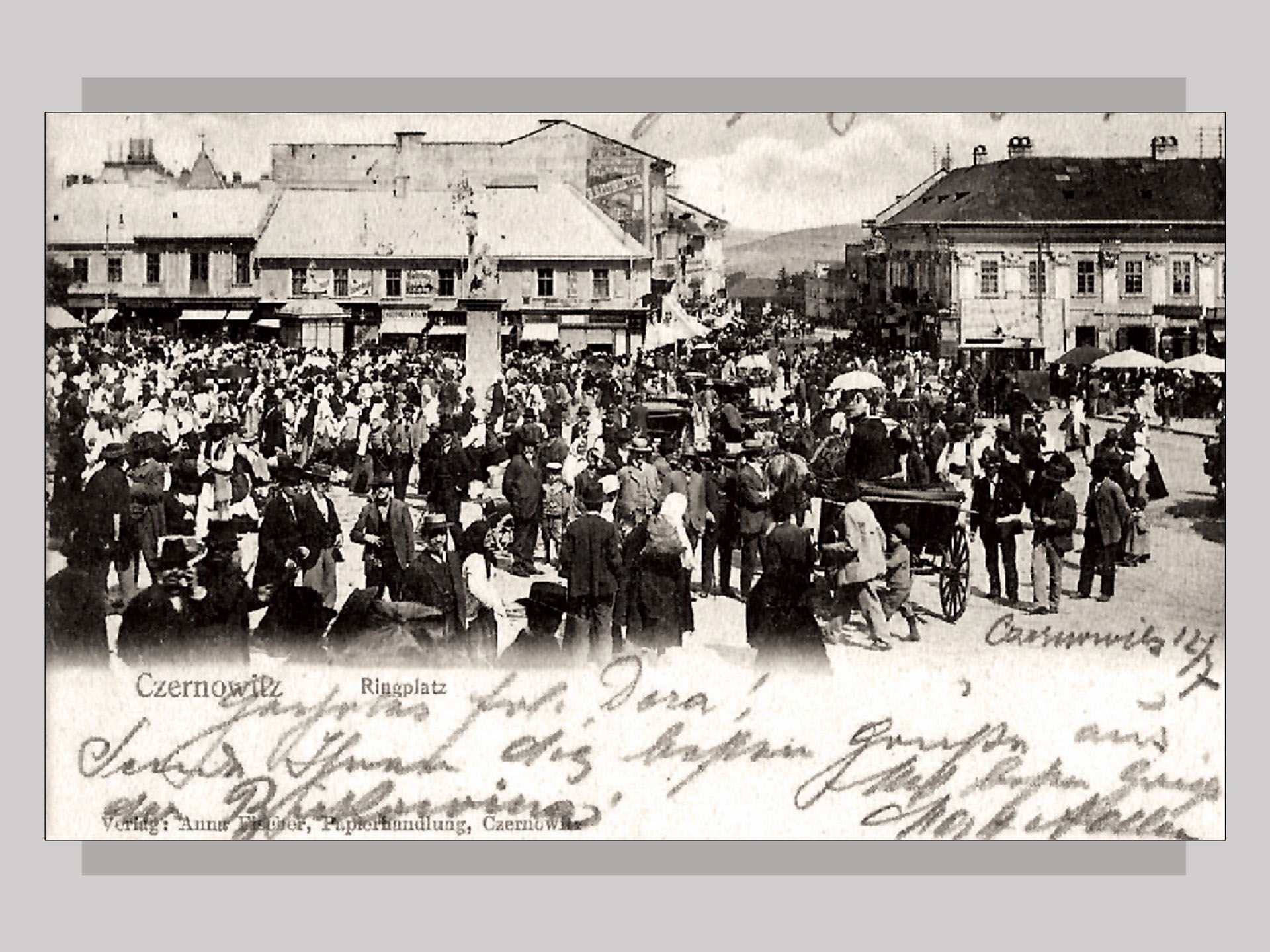

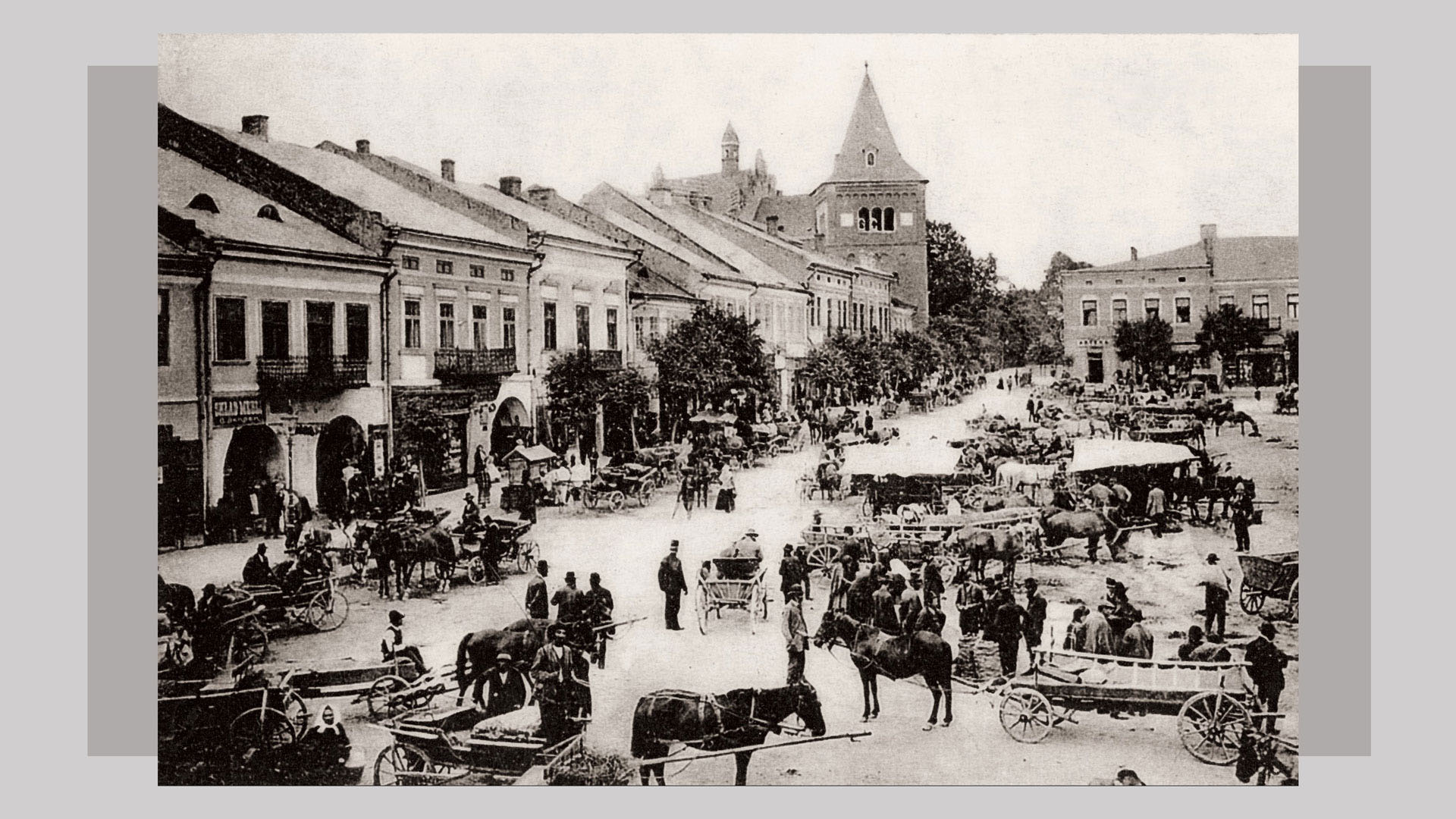

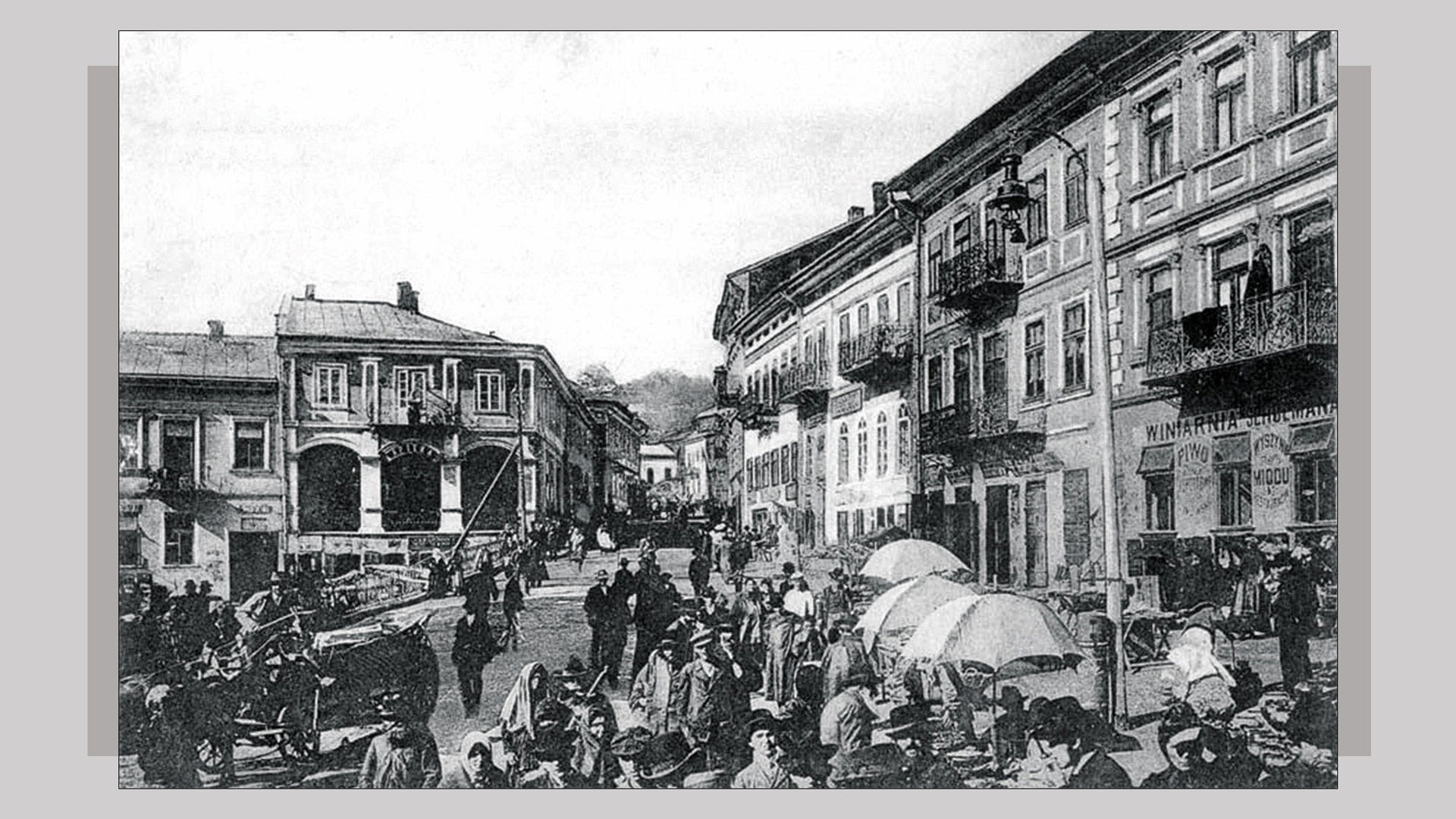

In largely agrarian Galicia, marketplaces in nearby towns, where Jews figured prominently, played a vital role in small-scale commerce and in people's lives. In 1900, 63 percent of Jews engaged in commerce and industry, 14 percent in agriculture, and 5 percent in civil service and the liberal professions.

Read more...

By 1910, 77 percent of Jews in Galicia were engaged in commerce, industry, and handicraft enterprises. A few Jews, who were prominent in banking, oil, trade, industry, and land ownership, were able to amass substantial wealth, while the vast majority of Galician Jews remained poor.

In 1910, 90.2 percent of the Ukrainians in Galicia, 72.3 percent of the Poles, and 10.7 percent of the Jews were employed in agriculture. In trade, the distribution was: 53 percent Jews, 8.7 percent Germans, 6.2 percent Poles, 2.3 percent Ukrainians; in industry: 24.6 percent Jews, 22.7 percent Germans, 11.6 percent Poles, 3.2 percent Ukrainians.

In 1912, Jews constituted 22 percent of the landowners in Galicia (mostly in East Galicia) — a higher percentage than anywhere else in the Habsburg Empire or Europe. Jews owned 342,000 hectares, 16 percent of the total area of privately owned landed estates in Galicia. There were, in addition, many Jewish leaseholders.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 420, 456, 464;

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. II,114, 115, 128.

1914

Transcarpathia

Before the First World War, Transcarpathia was the only region where the majority of the Jewish population worked in agriculture. They cultivated the land and raised cattle and sheep. They also worked as lumberjacks and loggers in villages nestled in the Carpathian Mountains.

sources

- Alexander Baran, "Jewish-Ukrainian Relations in Transcarpathia," in Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective, Peter Potichnyj & Howard Aster, eds. (Edmonton, 1988), 161–162.