1772–1914

Galicia, Bukovina, and Transcarpathia

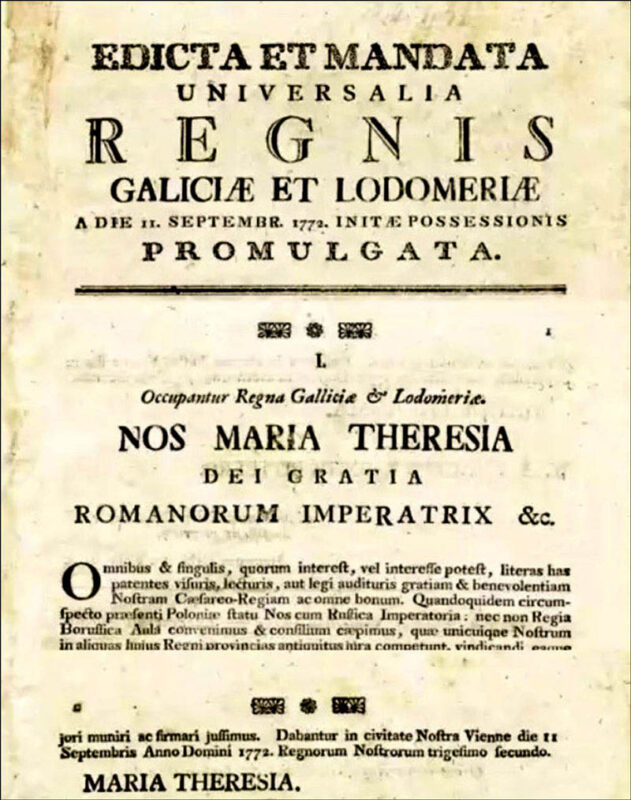

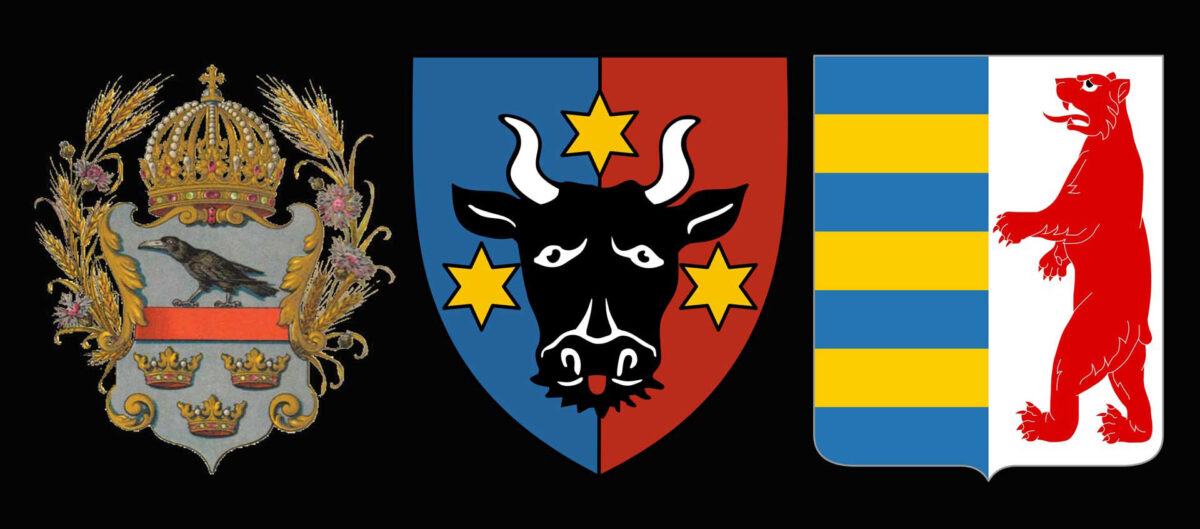

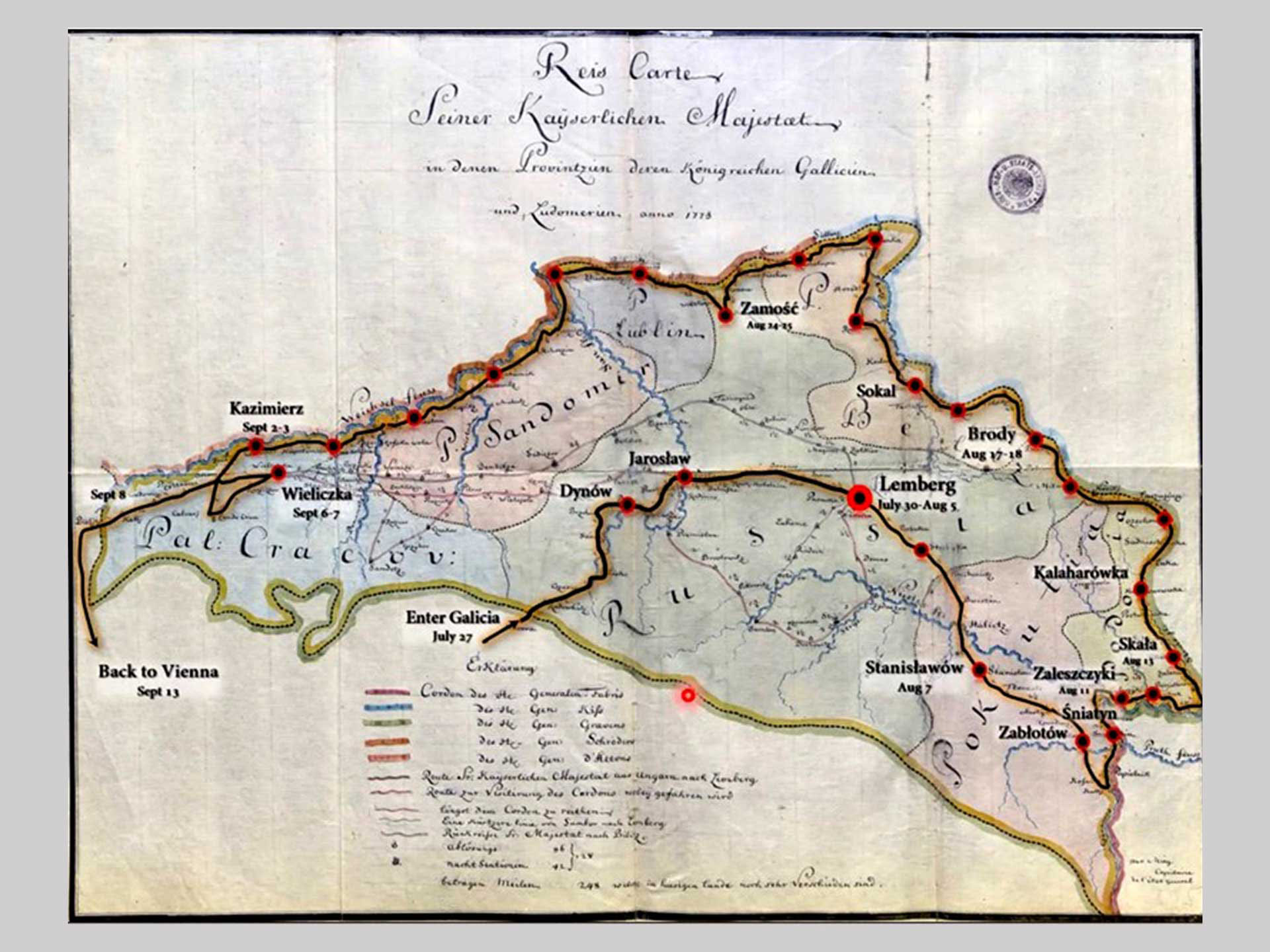

During the 1772 partition of Poland, Habsburg Austria claimed lands that had constituted the medieval Galicia-Volhynia Kingdom and absorbed them into the monarchy as a province named the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria. The new province, with Lemberg/Lviv as its capital, included the former Polish palatinates of Rus' (minus the Chełm region), Belz, parts of Podolia, and Cracow. It was the largest, most populous, and northernmost province of the Habsburg Empire until the dissolution of the monarchy in 1918. The population in the eastern half of the province was predominantly Ruthenian/Ukrainian and in the western half predominantly Polish. It was also one of the most densely populated areas of Jewish settlement in Europe.

Read more...

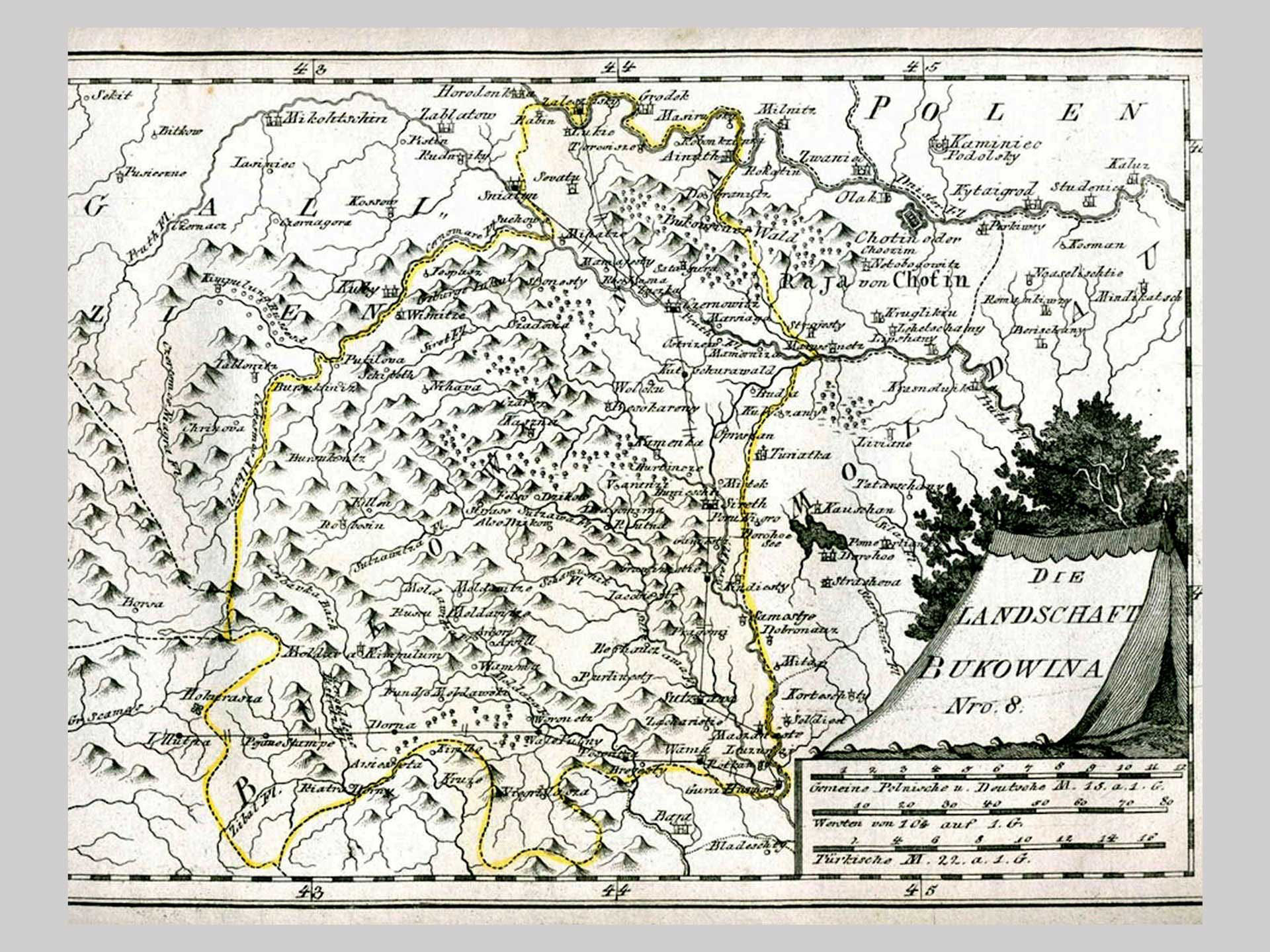

Austria annexed Bukovina as a military district, with the consent of the Ottoman Empire, after Austria occupied northwestern Moldova (1774). Bukovina was joined with Galicia in 1786, declared an autonomous crownland of the Austrian Empire in 1849, and a province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire from 1867 to 1918.

Transcarpathia (or historic Subcarpathian Rus'), part of the Kingdom of Hungary since the eleventh century, became part of the Austrian realm when the Habsburgs inherited the Hungarian throne in the sixteenth century. While the 1848–1849 Hungarian revolution against Austria failed, the political compromise that created the Austro-Hungarian Dual monarchy in 1867 brought Ukrainians and other national minorities in Transcarpathia under Hungarian rule.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 411–412, 441–443;

- Andrei Corbea-Hoisie, "Bucovina," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010);

- "Transcarpathia," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1993).

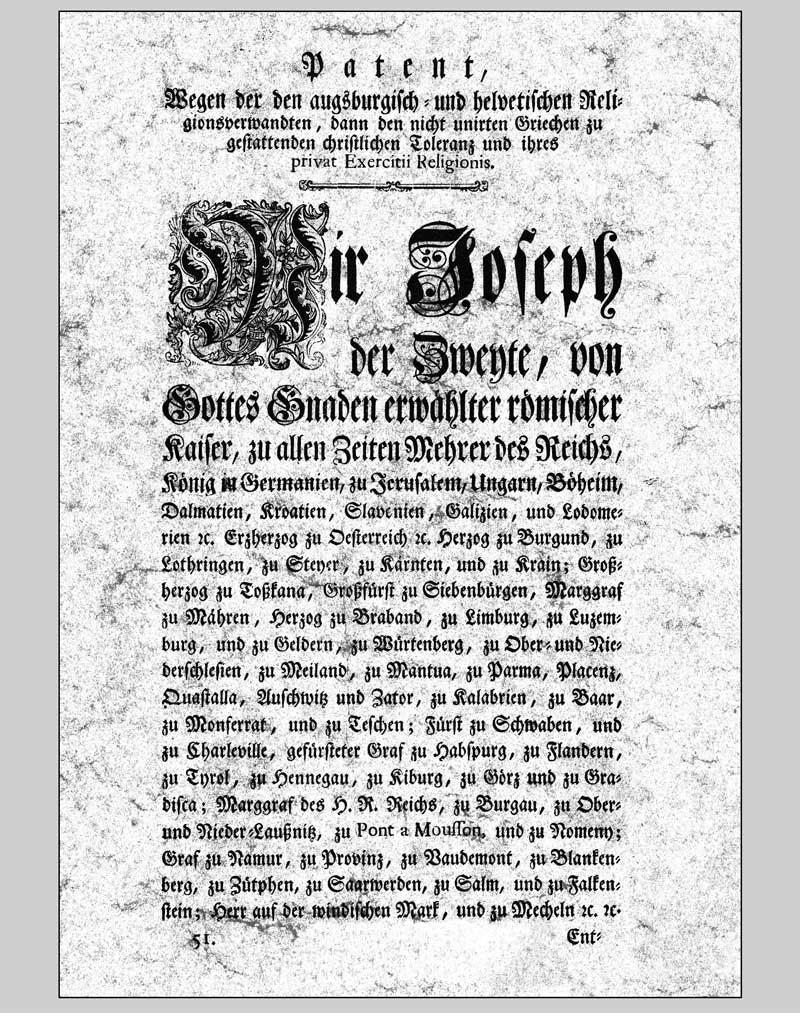

1773–1790

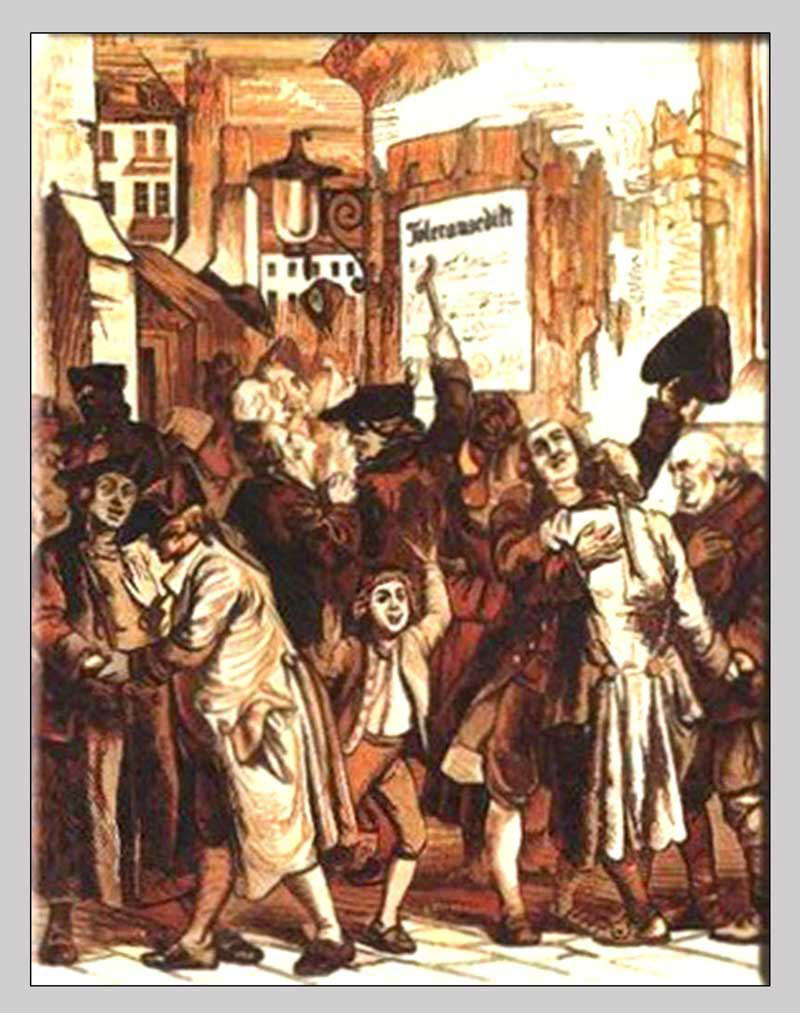

The Edict of Tolerance, issued by Habsburg Emperor Joseph II in 1781, extended religious freedoms to non-Roman Catholic Christians — a significant development for Greek Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Ukrainians in Galicia and Bukovina. At the same time, the Serfdom Patent strictly delimited the obligations of peasant-serfs, reducing their dependence on the arbitrary will of the noble landlord. Subsequent decrees further narrowed the rigours of serfdom — peasant-serfs were free to marry without the lord's permission, change their occupation, leave the land provided a replacement could be found, and seek justice in regular courts not controlled by landlords.

The Edict of Tolerance regarding Jews, issued in 1782, followed by additional decrees, regulations, and patents (summed up in the 1789 Galician Patent), had far-reaching consequences for the Empire's Jews, including those resident in Bukovina and Galicia. The aim was to 'reform' Jews, both economically and culturally — to diminish their 'separateness' and transform them into 'useful and productive' subjects.

Read more...

Joseph II's policies with respect to Jews had benefits but also limitations. In the political sphere, for example, Jews were granted restricted civic (municipal) rights, but these were dependent on the willingness of the burghers of the towns to concede such rights. The reforms had a strong impact in both the socioeconomic sphere and the cultural sphere. After the death of Joseph II, many of the reforms he had introduced concerning Jewish subjects were reversed or ignored for a time but reinstated in the latter half of the nineteenth century.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. I, 251–254;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 416–417, 420;

- Michael K. Silber, "Josephinian Reforms," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1830s–1840s

A generation of newly educated Ukrainians — beneficiaries of Austria's social, cultural, and educational reform — became the intelligentsia that by the 1830s emerged as the first awakeners of the Ruthenian/Ukrainian nationality. They also formed the political leadership of the Ruthenian movement during the revolution of 1848-49 and for some decades thereafter.

Lviv of the early 1830s is where the Galician literary group "the Ruthenian Triad" — Yakiv Holovatsky, Ivan Vahylevych, and Markiian Shashkevych, then students at the Greek Catholic Theological Seminary — made their mark on the Ukrainian national awakening. They collected Ukrainian folklore, studied the history of Ukraine, translated the works of Slavic authors, and wrote their own verses and treatises. Members of the group also advanced the idea that the Ruthenians of Galicia, Bukovina, and Transcarpathia were all part of one Ukrainian people, endowed with its own language, culture, and history.

sources

- “Lviv,” Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (article updated 2016);

- Danylo Husar Struk, "Ruthenian Triad," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1993).

1848

“Springtime of Nations” and Revolution in Galicia

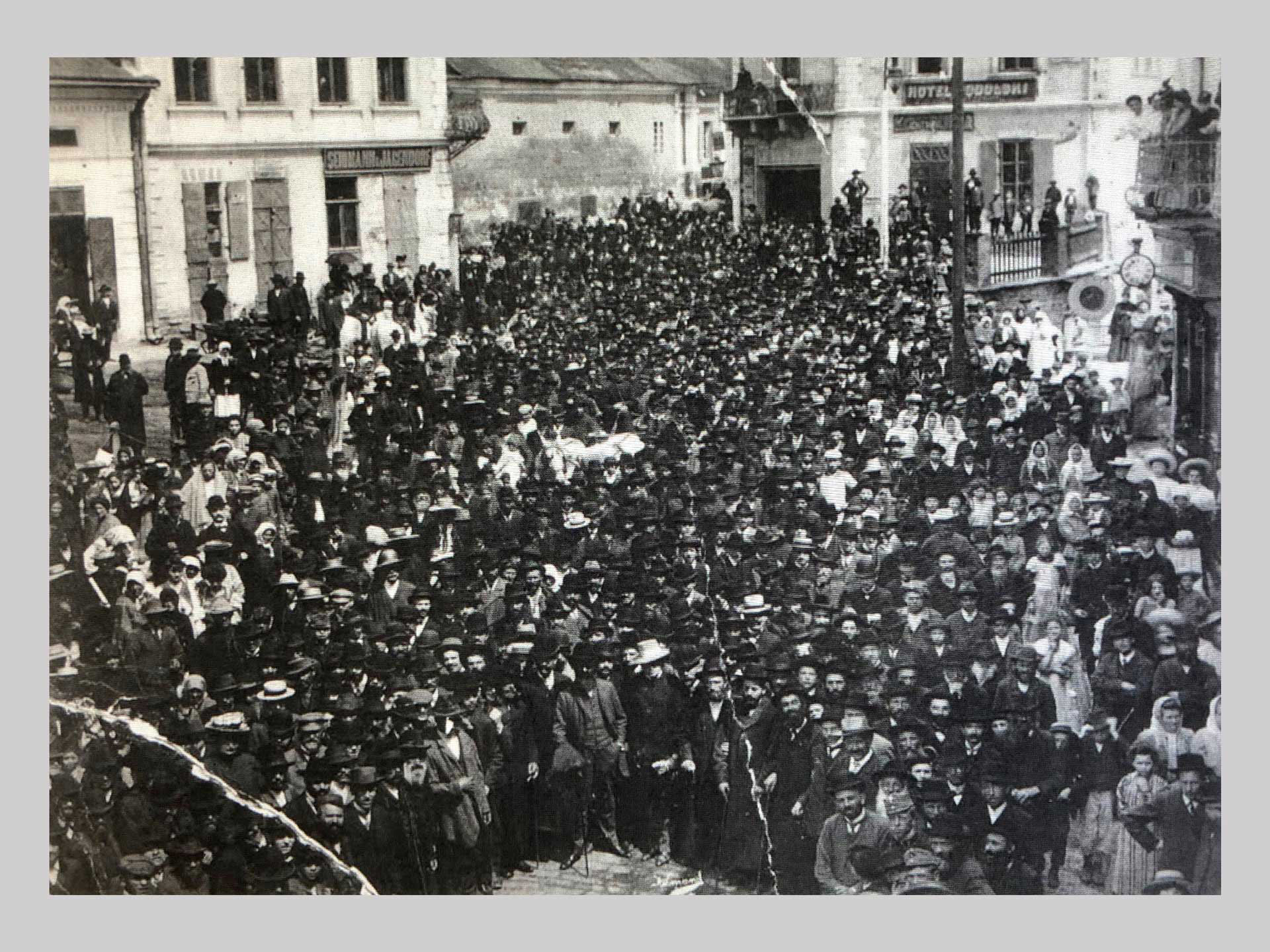

The revolutionary fervour that swept European countries in 1848 fueled a series of overlapping conflicts in the Habsburg Empire: liberal calls for representative government, peasant agitation for ending the labour tribute, and demands for recognition of the right to national self-determination. Referred to as the "Springtime of Nations," the revolution provided new impetus to the Polish and Ukrainian national movements, both increasingly active since the early 1830s. Leaders of the Jewish community were also inspired to campaign for recognition of their civil rights.

The Ukrainian cause had gained momentum with the abolition of serfdom in Galicia in April 1848, making the peasantry politically non-ignorable as the largest stratum of the Ukrainian population.

Read more...

Ukrainian political leaders did not hesitate to integrate the peasantry, with all its grievances and aspirations in the socioeconomic sphere, into the national movement.

Polish political activists, emboldened by the revolutionary atmosphere of 1848 to dream of the restoration of Polish statehood, formed a National Council to represent the Galician population and promote far-reaching autonomy for Galicia as a whole under the control of the Polish gentry. However, an abortive anti-Austrian Polish revolt in 1846 had perturbed the Austrian authorities, leading the governor of Galicia, Count Franz Stadion, to thwart Polish demands by encouraging Ukrainians' political and cultural goals.

In response, Ukrainian leaders established the Supreme Ruthenian Council to formulate their national demands, founded their own newspaper and their own cultural organization, and elected their own deputies to the Austrian parliament. Countering the Polish leaders' ambition, Ukrainian parties advocated the division of Galicia into separate eastern and western provinces, in which Ukrainians and Poles, respectively, would be dominant.

The times also inspired Jewish leaders to campaign for recognition of their civil rights. Since 1846, representatives of Galician Jewish communities (including Lviv, Brody, Stanyslaviv, Ternopil, Stryi, and Sambir) petitioned the Austrian authorities to remove special taxes imposed on Jews and other restrictions. It is the failure of these petitions which explains the widespread Jewish support in Galicia for the revolution of 1848.

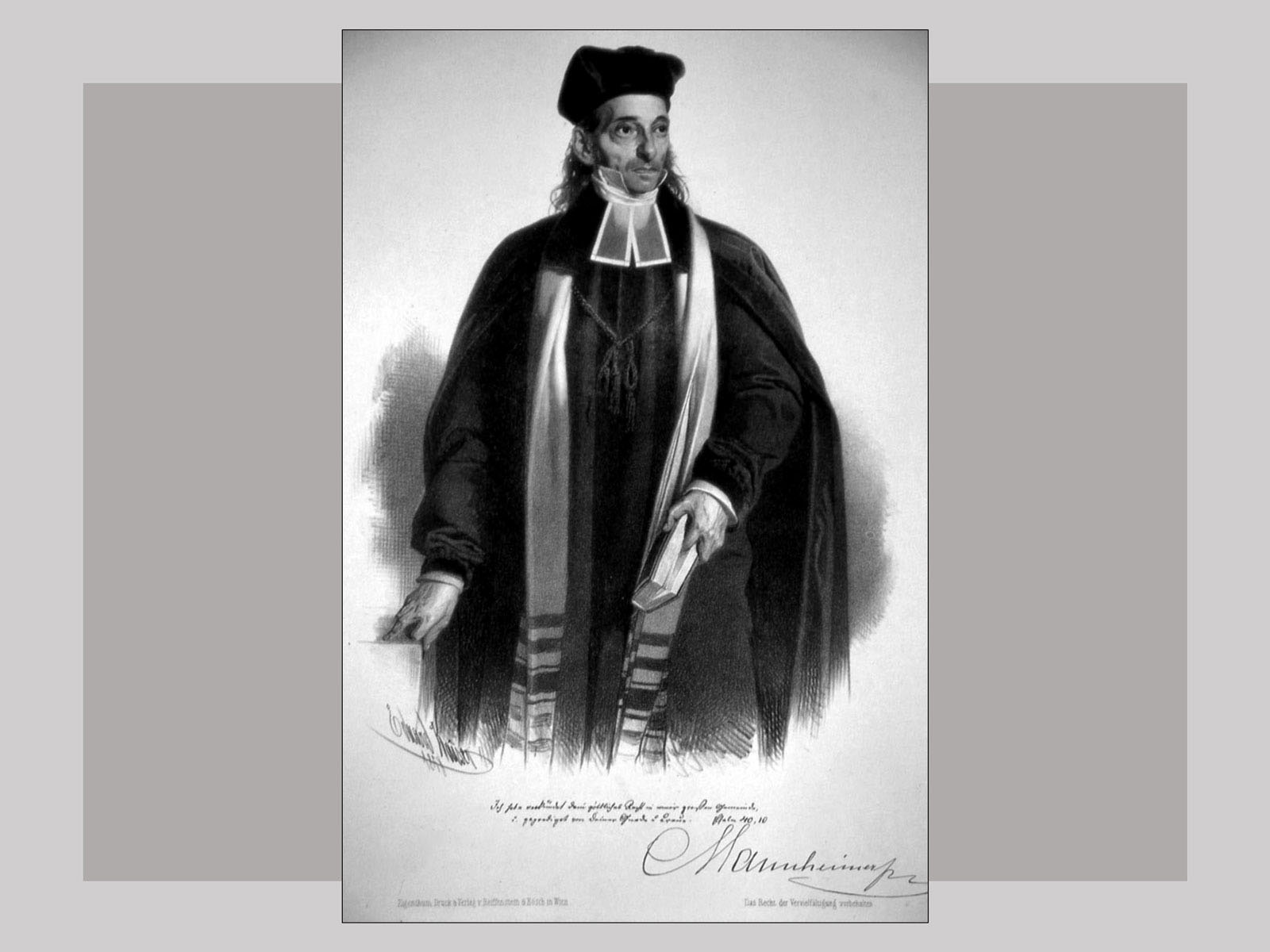

Two Jews from eastern Galicia were elected to the Reichsrat (the Austrian parliament) in 1848, including Rabbi Isaac Mannheimer from Brody (1793–1865) and Abraham Halpern (1818–1883) from Stanyslaviv. Their determined advocacy against Austrian discriminatory legislation affecting Jews contributed, by October 1848, to the Austrian parliament voting overwhelmingly to abolish all taxes levied on particular groups, including Jews.

sources

- Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 434–440;

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. I, 260, 263, 267;

- John-Paul Himka, "Dimensions of a Triangle: Polish-Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Austrian Galicia," Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry, vol. 12, Israel Bartal & Antony Polonsky, eds. (London/Portland, 1999), 29.

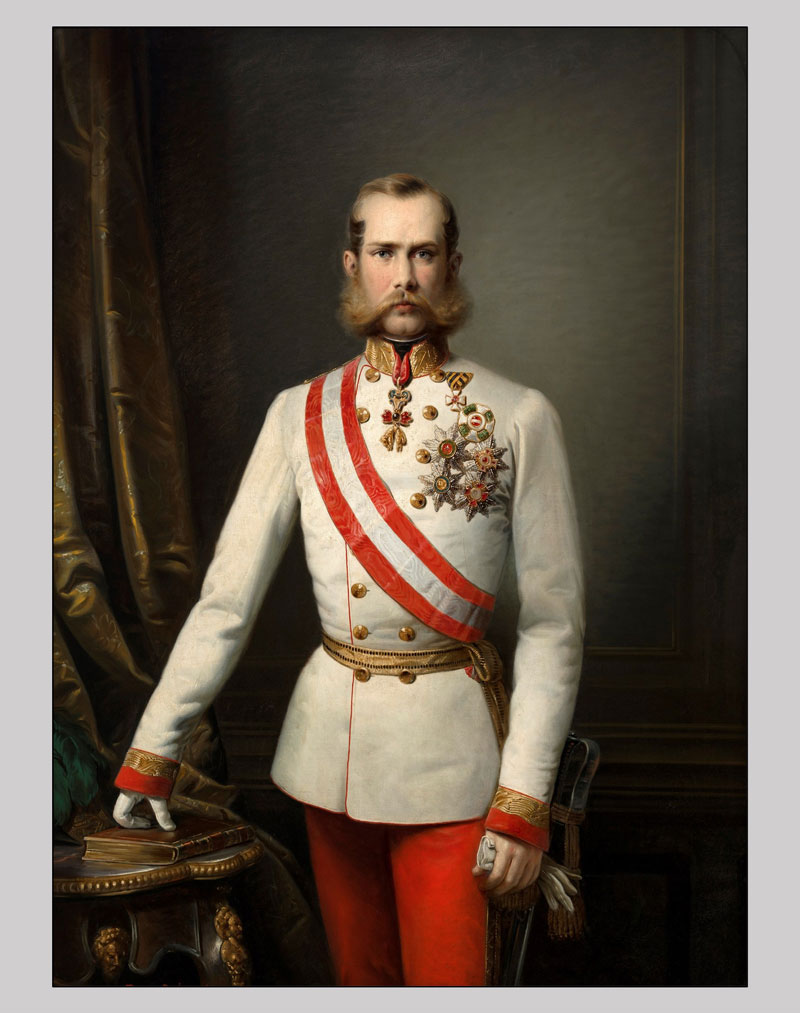

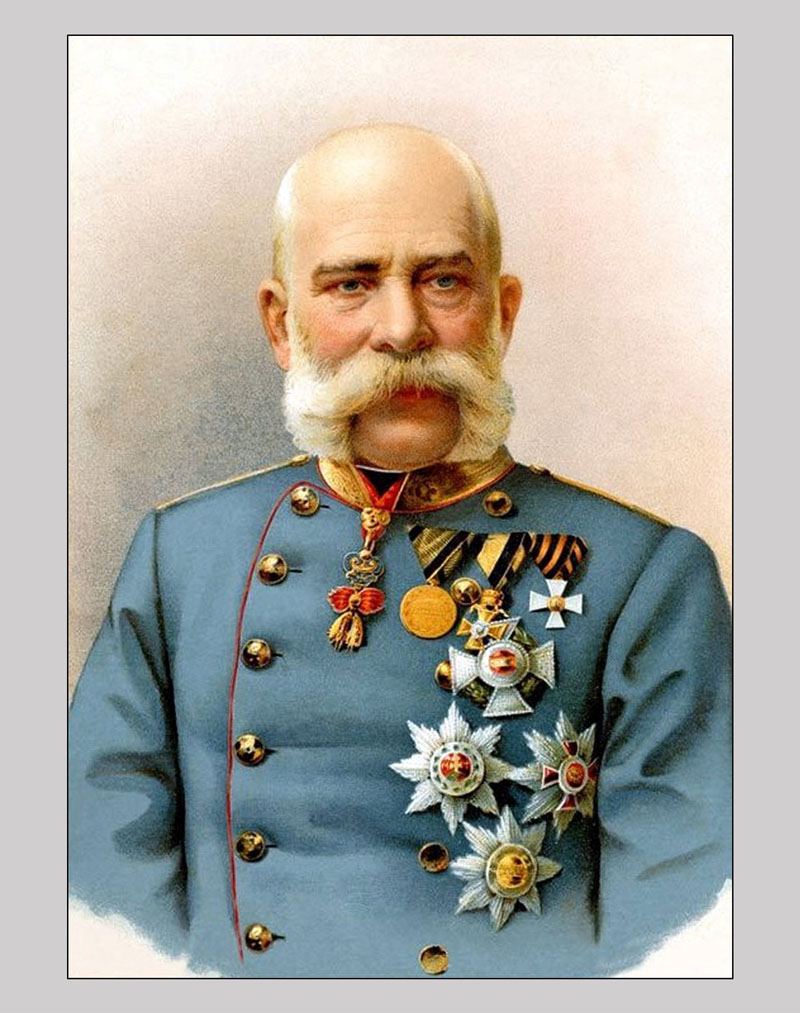

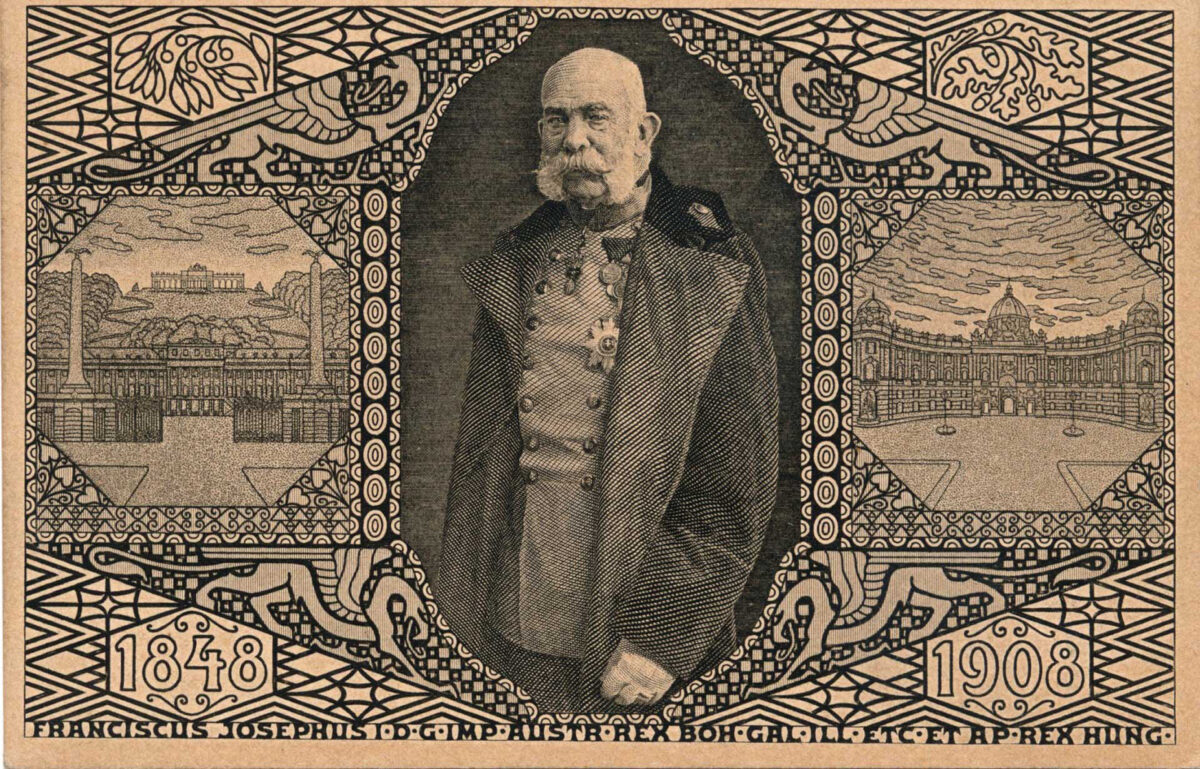

1848–1916

The 68-year benevolent reign of Franz Josef I ushered in an era of civil rights and cultural development for both Ukrainians and Jews living in the Habsburg Empire. A far-reaching development for Ukrainians was the abolition of serfdom in 1848, enabling many to become economically independent of their former landlords. In 1867, Jews in the Habsburg Empire were granted full civil rights, including the right to purchase land, join trade guilds, hold government posts, and be employed as university professors. In an environment that permitted multiple identities and loyalties, both Ukrainians and Jews were able to become politically active, make far-reaching educational strides, and produce leaders for their respective national awakenings. As proud Habsburg subjects, the Jews of Galicia, Bukovina, and Transcarpathia had much warmer feelings toward "their" emperor Franz Josef than did the Jews in Russian-ruled Ukraine toward Tsar Nicholas II — a ruler associated with the pogromist Black Hundreds and the notorious antisemitic work, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. I, 262–272.

1860s–1868

Though Jews in the Austrian Empire, including in Galicia, were granted full civil rights, restrictions prevailed in Lviv. Municipal regulations introduced in Lviv in 1863 and 1866 restricted the number of Jewish councillors to 15 percent of the total. As Oswald Hönigsmann, a Jewish deputy to the Galician Sejm of 1868, noted, "One can safely say that in order to emancipate the Jews, one must first emancipate oneself from prejudices and imaginary fears."

Austrian policy after 1868 increasingly tended to accommodate Galicia's Poles, allowing them to run the administration of the province. As a result, Ukrainian political, civic, and educational initiatives often encountered Polish opposition. The Russophile tendency that dominated Ukrainian politics from the 1860s also undermined the Ukrainian cause in Galicia as it was internally divisive, evoked suspicion, and triggered opposition from the Austrian authorities.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. I, 269–272;

- John-Paul Himka, "Dimensions of a Triangle: Polish-Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Austrian Galicia," Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry, vol. 12, Israel Bartal & Antony Polonsky, eds. (London/Portland, 1999), 32–33;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Ukraine: An Illustrated History (Toronto, Second Edition, 2007), 184.

1867–1869

The liberal constitution of December 1867 established full legal equality for all citizens of the Habsburg empire regardless of religious belief or nationality, opening new avenues for public activity and opportunities for strategic alliances for both Ukrainians and Jews.

As Galicia was granted broad autonomy following the reconfiguration of the empire as the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary, Jews generally favoured an alliance with the politically dominant Poles. Yet, most of the province's Jews lived in the predominantly Ukrainian eastern part of the province, at a time when the Ukrainian national movement was growing increasingly assertive.

Read more...

Importantly, the new constitution defined Ruthenians (Ukrainians) as a people (Volksstamm) — as a recognized nationality. Jews were defined as a separate religious community (Religionsgemeinschaft), not a nationality. Consequently, Yiddish did not receive official approval for use in schools and public life. The requirement for Israeliten (Jews) was that they seek their place among the non-Jewish 'nationalities' and consider themselves Poles or Germans of the Mosaic faith. The majority 'nationalities' therefore initiated a campaign to persuade Jews to join their ranks, with the result that a Jewish response in one direction or another often provoked antisemitic reactions. Only in Bukovina, where no nationality had a majority, were Jews recognized as a de facto "nationality."

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. I, 262–272;

- Piotr Wrobel, "The Jews of Galicia under Austrian-Polish Rule, 1867–1918," Austrian History Yearbook, Vol. 25, January 1994, 3–4.

1868

In Transcarpathia, a proclamation by the Hungarian Parliament exerted pressure on both Jews and Ukrainians to assimilate to Magyar culture. The stated view was that "all citizens of Hungary constitute a single nation, the indivisible, unitary Magyar nation," making it difficult for non-Magyar communities to express and maintain their particular cultures in organized ways.

sources

- Alexander Baran, "Jewish-Ukrainian Relations in Transcarpathia," in Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Historical Perspective, Peter Potichnyj & Howard Aster, eds. (Edmonton, 1988), 162–63.

1850s–1900s

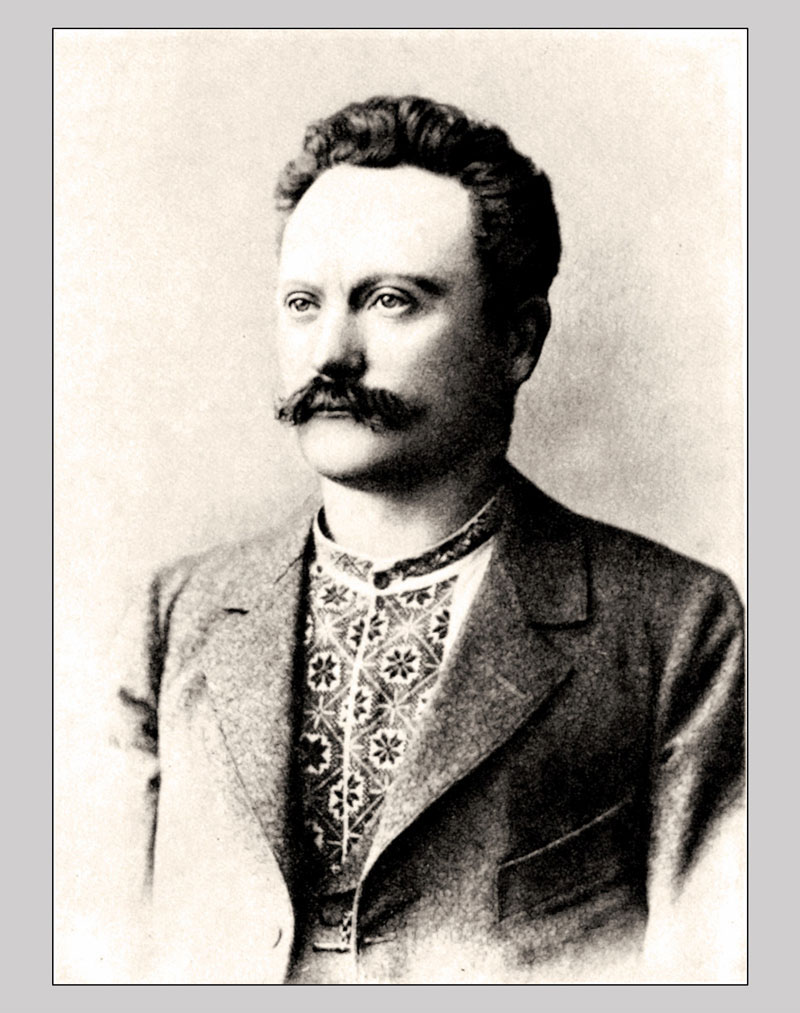

Ukrainian National Awakening

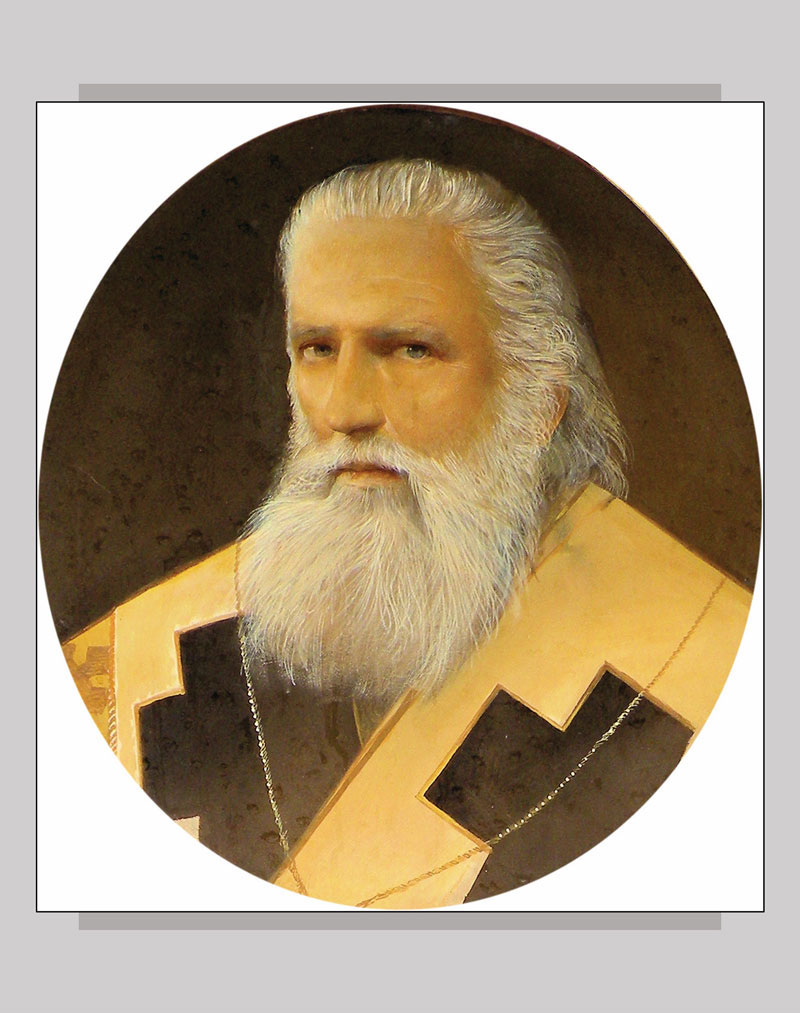

The Ukrainian national awakening made remarkable progress in Galicia and neighbouring Bukovina, both under Habsburg rule. It also made progress in Hungarian-ruled Transcarpathia until 1868, when it was subjected to an aggressive Magyarization policy. The national awakening was led by such notable Ukrainian political, religious, and cultural figures as Aleksander Dukhnovych, Yurii Fedkovych, Mykhailo Hrushevsky, Ivan Franko, and Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky. Remarkable achievements during this period include codification and broadened use of the Ukrainian language, especially in the educational system, and the nurturing of cultural life and Ukrainian affiliation through a network of Ukrainian cooperatives, credit associations, and cultural institutions. Ukrainian newspapers and publishing houses flourished, and the equivalent of a Ukrainian academy of sciences — the Shevchenko Scientific Society — was established. Ukrainians also created political parties and sent deputies to defend Ukrainian interests in both the Galician provincial diet and the Austrian imperial parliament. Major challenges had to be overcome to achieve these results, primarily the relentless opposition from Galicia's Polish administration and internal division, including lack of support from Ukrainian Russophiles.

sources

- Paul Robert Magocsi, Ukraine: An Illustrated History (Toronto, Second Edition, 2007), 183–190, 193;

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (Toronto, Second Edition, 2010), 472–476.

1869–1900s

Jews held a pivotal and uncomfortable position in Galicia's politics, particularly after Galicia attained autonomy. Because of the delicate Polish-Ukrainian-Jewish population balance, Ukrainian and Polish politicians competed fiercely for the Jewish swing vote, which could determine either a Polish or a Ukrainian majority in the province. Not surprisingly, the role of Jews in preserving Polish hegemony provoked both bitter Ukrainian resentment and occasional attempts (as in 1873 and 1907) to form Ukrainian-Jewish tactical alliances to challenge Polish political control.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. II, 119.

1879–1880

Leaders of the political party Mahzikei Hadas (Upholders of the Faith) held their first meeting (in Lviv) and elected Rabbi Shimon Sofer (Schreiber), the communal rabbi of Cracow, as the party's first president. The goal of the party was to unite traditional Orthodox Jews across Galicia against the threat of the modernists, in particular, the Shomer Yisrael organization. In 1880, Rabbi Sofer was elected to the Reichsrat (Austrian parliament) for the Kolomyia-Buchach-Sniatyn district and joined the Polish Club. He explained his support for the politically dominant Poles as follows: "Our religion...tells us to seek the welfare of the people among whom we live. I will go together with the Poles to the parliament, and I will agree with what they consider to be good for the state and the monarchy."

sources and related

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. II, 120–122.

Related

Chapter 5.4 1868–1883

1887–1892

A branch of Hovevei Zion (Lovers of Zion), one of the main precursor organizations to the Zionist movement, was established in Lviv in 1887; the aim of the organization was to further Jewish settlement, in particular agricultural settlement in the land of Israel. By the mid-1890s, various groups with similar goals attracted around 4,000 members.

In contrast, the Jewish National Party of Galicia, founded in Lviv in 1892, adopted a dual program — the creation of a Jewish homeland in Palestine as a long-term goal, while simultaneously pursuing Jewish national rights in Galicia.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. II, 136.

1890s–1914

Jewish Political Parties

Jews participated actively in Galician politics during this period from diverse standpoints. Some embraced the Polish national cause; others allied themselves with Polish and Ukrainian socialists whose primary interest was to transform Galicia's socioeconomic system. For another faction — the Zionists — emigration to Palestine was the avenue for Jewish salvation. Among these, many were more inclined than were western European Zionists to seek better political representation for Jews while living in Europe. Since the early 1890s, the Jewish National Party of Galicia adopted what was described as a 'dual program' calling for the creation of a Jewish homeland in Palestine as a long-term goal, to be pursued simultaneously with the development of a 'Jewish national consciousness' and the achievement of Jewish national rights in Galicia.

Read more...

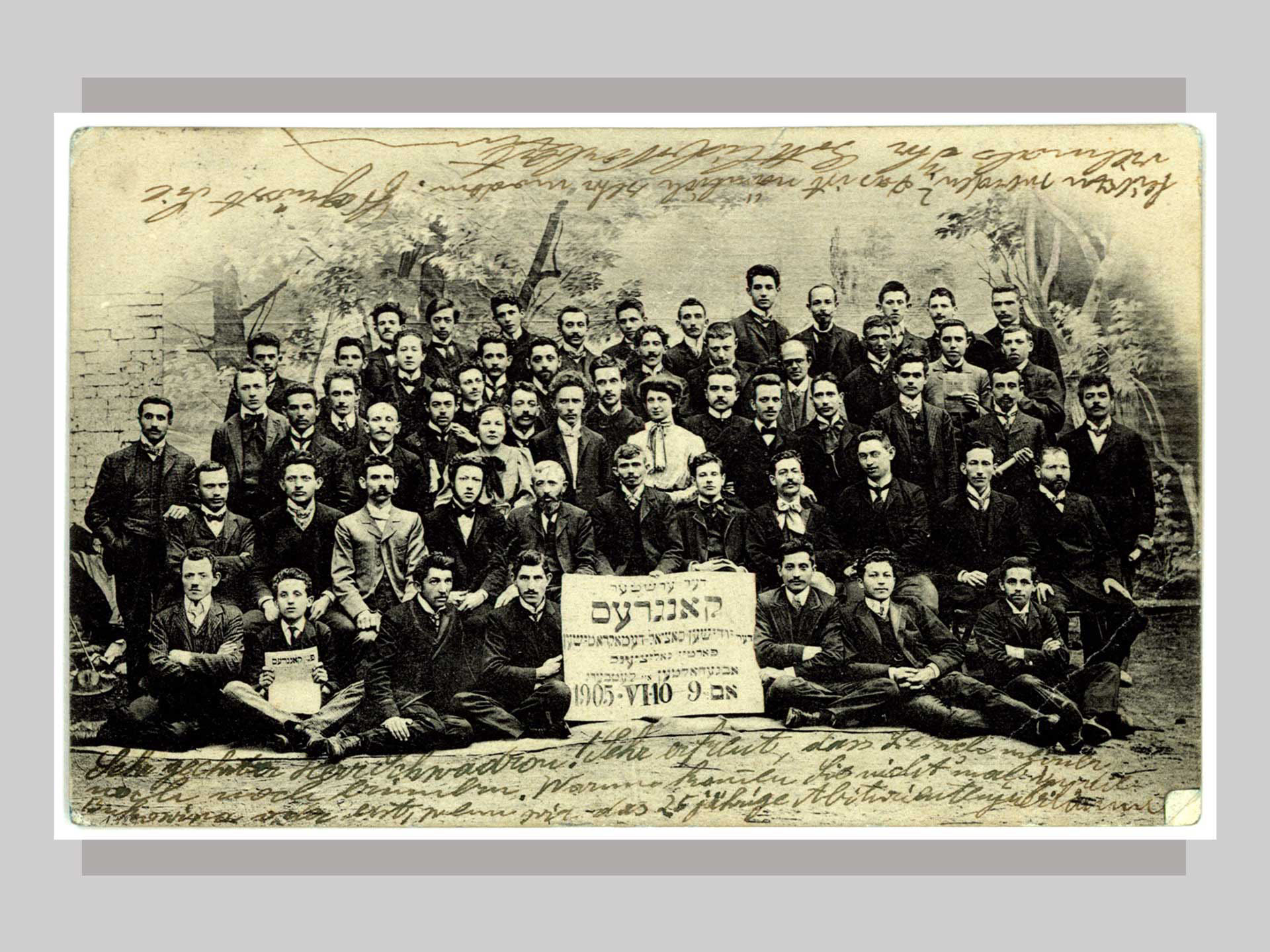

After the Austrian parliament voted on universal adult male suffrage in 1906, Zionists in Galicia founded the Jüdische Politische Nationalpartei (Jewish National Party), and other Jewish political parties also became active in Austrian Galicia. Of the 62,609 votes cast for various Jewish parties in Galicia, 24,274 went to Zionists, 17,581 to Socialists, and 18,885 to the Polska Organizacja Żydowska (Polish Jewish Organization).

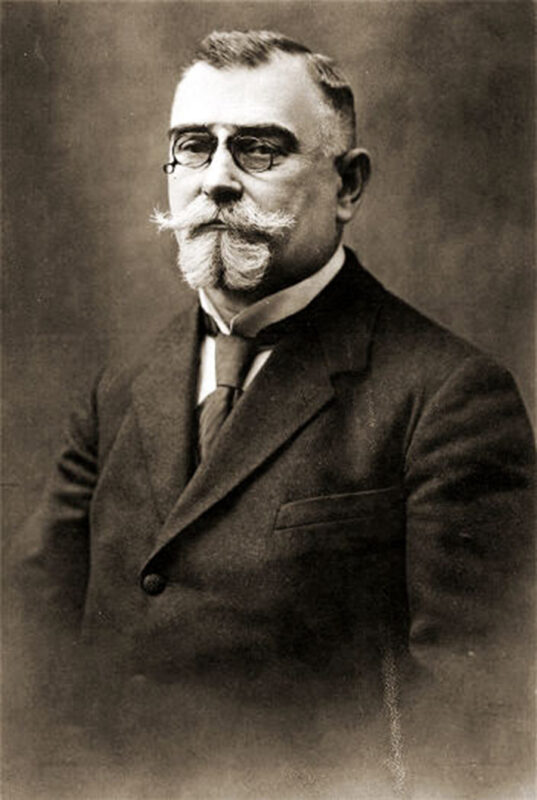

The career of author and publicist Nathan Birnbaum encapsulates the diverse political paths attracting Jews in pre-World War I Galicia. During his Zionist phase (1883–1900), Birnbaum co-founded Kadimah, a Jewish nationalist student society and launched a Jewish periodical in which he coined the term 'Zionism' and which served (until 1892) as the de facto organ for Galician Zionists. He also played a prominent part in the First Zionist Congress in Basel in 1897, where he was elected Secretary-General of the Zionist Organization.

In his second phase (1900–1914), Birnbaum threw himself into the political struggle for Jewish national-cultural autonomy, advocating for the Jews to be recognized as a people among the other peoples of the empire, with Yiddish as their official language. This perspective motivated him to organize the 1908 Yiddish Language Conference in Czernowitz (Chernivtsi). During this period, Birnbaum was also well-known as an advocate of Jewish-Ukrainian cooperation in Galicia, frequently promoting this alliance against the dominant Poles in his short-lived paper Neue Zeitung (1906–1907). In a third phase, beginning in 1914, he turned to Orthodox Judaism and became staunchly anti-Zionist.

sources

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. II, 136–146;

- Ury, Scott, "Zionism and Zionist Parties," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010);

- Joshua Shanes, "Birnbaum, Nathan," YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2010).

1899

The Ukrainian National Democratic Party

The centrist Ukrainian National Democratic Party (UNDP), which united Ukrainophile populists and social radicals, was founded by Ivan Franko, Yuliian Romanchuk, Kost' Levytsky, and Mykhailo Hrushevsky. The UNDP declared Ukrainian independence as its ultimate aim. Its immediate goals were also ambitious: division of Galicia into Ukrainian and Polish territories; uniting all Ukrainians in Austria-Hungary (in Galicia, Bukovina, and Hungary) in a separate province with its own regional government; solidarity of Ukrainians across the Austrian-Russian divide; and equality of ethnic groups in the empire. These aspirations ran counter to those of Polish political parties. The Polish National Democratic Party, led by Roman Dmowski, sought to assimilate Ukrainians into Polish culture. In contrast, the Polish socialists, led by Józef Piłsudski (future leader of the independent Polish state), advocated a federal arrangement for Ukrainians living in western Ukraine, rather than independence. The Ukrainian National Democrats failed to achieve partition of the province and attainment of Ukrainian autonomy within Austria-Hungary. However, they did succeed in promoting an extensive educational and cultural agenda and created a robust social base by establishing credit unions and village cooperatives. While the UNDP officially rejected antisemitism and supported Zionism, it held Jews responsible for maintaining Polish rule in Eastern Galicia.

sources

- Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe (New York, 2015), 195–196;

- Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia (Oxford/Portland, 2010), vol. II, 131;

- Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern and Antony Polonsky, Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry, Volume 26, Jews and Ukrainians, (Oxford, 2014), 22;

- Vasyl Mudry, "National Democratic Party," Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine (1993).

1907

Ukrainian and Jewish national activists in Austrian Galicia forged a political alliance in 1907, during Austria's first parliamentary elections under universal male suffrage. Ukrainian nationalists believed that a more nationalist Jewish community would undermine Polish hegemony in Galicia. At the same time, some Zionists saw in this alliance the potential to elect Jewish parliamentary representatives in rural Ukrainian districts where they were competing against Polish politicians. The alliance was a qualified success. It led to a more robust national Ukrainian faction and the first Zionist faction in any European parliament. Although not repeated in the 1911 elections, the alliance sparked a pro-Ukrainian discourse in Jewish politics and a pro-Zionist one in Ukrainian politics. It also placed Zionism in the context of European-wide national awakenings of the period, not only as a reaction to rampant turn-of-the-century racial antisemitism.

sources

- Joshua Shanes, Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, "An Unlikely Alliance: The 1907 Ukrainian-Jewish Electoral Coalition," Nations and Nationalism 15 (3) (2009): 483–505.